War of the Russian Army Wrangel

Smoot. 1920 year. Crimea, as a base and strategic base for the revival of the White movement, was inconvenient. Lack of ammunition, bread, gasoline, coal, horses, help weapons from the allies made the defense of the Crimean bridgehead unpromising.

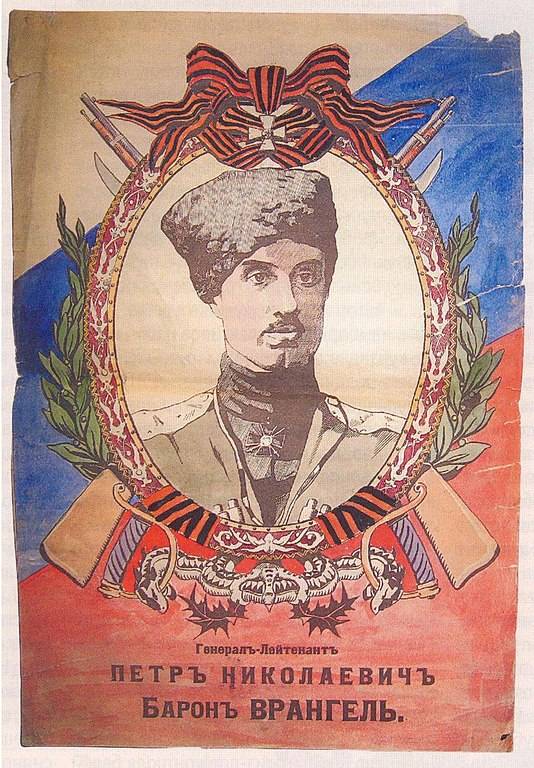

The Black Baron

When Wrangel took command of the Armed Forces of the South of Russia in early April 1920, he was 42 years old. Pyotr Nikolaevich came from an old noble family of Danish origin. Among his ancestors and relatives were officers, military leaders, navigators, admirals, professors and entrepreneurs. His father, Nikolai Yegorovich, served in the army, then became an entrepreneur, engaged in oil and gold mining, and was also a famous collector of antiques. Peter Wrangel graduated from the Mining Institute in the capital, was an engineer by training. And then he decided to go to military service.

Wrangel enlisted as a volunteer in the Life Guards Horse Regiment in 1901, and in 1902, having passed the exam at the Nikolaev Cavalry School, he was promoted to guard cornet with enrollment. Then he left the army and became an official in Irkutsk. With the start of the Japanese campaign, he volunteered to return to the army. He served in the Transbaikal Cossack army, bravely fought with the Japanese. He graduated from the Nikolaev Military Academy in 1910, in 1911 - a course of the Officer Cavalry School. He met the World War with the squadron commander of the Life Guards of the cavalry regiment in the rank of captain. In the war he proved himself to be a brave and skillful cavalry commander. He commanded the 1st Nerchinsk regiment of the Transbaikal army, the brigade of the Ussuri equestrian division, the 7th cavalry division and the Consolidated cavalry corps.

Bolsheviks did not accept. He lived in Crimea, after the German occupation, went to Kiev to offer his services to the hetman Skoropadsky. However, seeing the weakness of the Hetman, he went to Yekaterinodar and headed the 1st Cavalry Division in the Volunteer Army, then the 1st Cavalry Corps. He was one of the first to use cavalry in large formations in order to find a weak spot in the enemy’s defense and to reach his rear. He distinguished himself in battles in the North Caucasus, the Kuban and in the Tsaritsyn area. He led the Caucasian Volunteer Army in the Tsaritsyno direction. He came into conflict with the headquarters of Denikin, because he believed that the main blow should be done on the Volga in order to quickly connect with Kolchak. Then he repeatedly intrigued against the commander in chief. One of the leading qualities of the personality of the baron was the desire for success, careerism. In November 1919, after the defeat of the White Guards during the offensive in Moscow, he led the Volunteer Army. In December, due to disagreements with Denikin, he resigned and soon left for Constantinople. In early April 1920, Denikin resigned, Wrangel led the remnants of the White Army in the Crimea.

White Guards in Crimea

At the time of assuming the post of Commander-in-Chief Wrangel, his main task was not to fight the Bolsheviks, but to preserve the army. After a series of catastrophic defeats and the loss of almost the entire territory of the white South of Russia, almost no one thought about active actions. The defeat seriously affected the morale of the White Guards. Discipline collapsed, hooliganism, drunkenness and unbridledness became commonplace in the evacuated parts. Robberies and other crimes have become commonplace. Some units left the submission, turned into a gang of deserters, marauders and bandits. In addition, the material condition of the army was undermined. In particular, Cossack units were taken to the Crimea almost without weapons. In addition, the Don people dreamed of going to the Don.

A heavy blow to the White Army was dealt by the "allies." They practically refused to support the White Guards. France, refusing to interfere in Crimean affairs, now relied on buffer states, primarily on Poland. Only in the middle of 1920 did Paris recognize the Wrangel government as a de facto Russian government and promised to help with money and weapons. Britain generally demanded an end to the struggle and compromise with Moscow, conclude an honorable peace, receive amnesty or free travel abroad. This position of London led to a complete disorganization of the White movement, the loss of faith in a future victory. In particular, the British finally undermined the authority of Denikin.

Many believed that the White Army in the Crimea was a trap. The peninsula had many vulnerabilities. The Red Army could organize an assault from Taman’s side, attack on Perekop, along the Chongar Peninsula and the Arabat Spit. The shallow Sivash was more a swamp than a sea, and was often passable. AT stories All the conquerors took the Crimean peninsula. In the spring of 1919, the Reds and Makhnovists easily occupied Crimea. In January, February and March 1920, Soviet troops broke through to the peninsula and were repelled only thanks to General Slaschev’s maneuverable tactics. In January 1920, Soviet troops captured Perekop, but the sugary counter-attack knocked out the enemy. In early February, the Reds crossed the ice of the frozen Sivash, but were driven back by Slashchev’s corps. On February 24, Soviet troops broke through the Chongar crossing, but were driven back by the White Guards. On March 8, the strike group of the 13th and 14th Soviet armies again took Perekop, but was defeated at the Ishun positions and retreated. After this failure, the Red Command for a while forgot about the White Crimea. A small barrier from the 13th Army units (9 thousand people) was left near the peninsula.

The talented military leader Slashchev did not rely on strong fortifications, which were not there. He left ahead only posts and patrols. The main forces of the corps were in winter apartments in settlements. The Reds had to go in frosts, snow and wind through desert areas where there were no shelters. Tired and frozen fighters crossed the first line of fortifications, and at that time fresh reserves of Slashchev approached. The white general had the opportunity to concentrate his small forces on a dangerous site and smashed the enemy. In addition, the Soviet command first underestimated the enemy, aiming at the Kuban and the North Caucasus. Then the Reds believed that the enemy had already been defeated in the Caucasus and that the miserable remnants of the whites in the Crimea would be easily dispersed. Slashchev’s tactics worked until the Soviet command concentrated superior forces, and especially the cavalry, which was able to quickly pass Perekop.

The Crimean peninsula as a base and strategic bridgehead for the revival of the White movement was weak. Unlike the Kuban and Don, Little Russia and New Russia, Siberia and even the North (with its huge reserves of weapons, ammunition and ammunition in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk), Crimea had insignificant resources. There was no military industry, developed agriculture and other resources. The absence of ammunition, bread, gasoline, coal, horse-drawn personnel, and weapons assistance from the Allies made the defense of the Crimean bridgehead unpromising.

Due to refugees, evacuated white troops and rear institutions, the population of the peninsula doubled, reaching a million people. Crimea could barely feed so many people on the brink of hunger. Therefore, in the winter and spring of 1920, Crimea was struck by the food and fuel crisis. A significant part of the refugees were women, children and the elderly. Again, a mass of healthy men (including officers) squandered life in the rear in the cities. They preferred to participate in all kinds of intrigues, arrange a feast during the plague, but did not want to go to the front lines. As a result, the army did not have a human reserve. There were no horses for the cavalry.

Thus, white Crimea was not a serious threat to Soviet Russia. Wrangel, who did not want peace with the Bolsheviks, had to figure out the possibilities of a new evacuation. The option of deploying troops with the help of allies to one of the existing fronts of the war with Soviet Russia was considered. To Poland, the Baltic states or the Far East. It was also possible to take the White Army to one of the neutral countries in the Balkans so that the Whites could have a rest, restore ranks, arm themselves and then could take part in a new Western war against Soviet Russia. A significant part of the White Guards hoped to just sit out in Crimea in anticipation of a new large-scale uprising of the Cossacks in the Kuban and Don or the outbreak of the Entente war against the Bolsheviks. As a result, a change in the military-political situation led to the decision to maintain the Crimean bridgehead.

"New Deal" Wrangel

Wrangel, having gained power on the peninsula, proclaimed a "new course", which, in fact, due to the absence of any new program, was an audit of the policies of the Denikin government. At the same time, Wrangel abandoned the main slogan of the Denikin government - “a united and indivisible Russia”. He hoped to create a wide front of the enemies of Bolshevism: from the right to the anarchists and separatists. He called for building a federal Russia. Recognized the independence of the highlanders of the North Caucasus. However, such a policy did not bring success.

Wrangel was never able to agree with Poland on common actions against Soviet Russia, although he tried to be flexible in the matter of future borders. Attempts to plan general operations did not go further than talk, despite the desire of the French to bring the Poles and the White Guards closer. Obviously, the point is the nearsightedness of the Pilsudski regime. Pans hoped for the restoration of the Commonwealth within the borders of 1772 and did not trust the whites - as Russian patriots. Warsaw believed that the fierce battle between the whites and the reds so weakened Russia that the Poles themselves could take whatever they want. Therefore, Warsaw does not need an alliance with Wrangel.

With Petliura, Wrangel also could not conclude an alliance. Only spheres of influence and theaters of operations in Ukraine were identified. The Wrangel government promised the UPR full autonomy. At the same time, the Petliurites no longer had their territory, their army was created by the Poles and was the fruit of their complete control. The baron also promised the complete autonomy of all Cossack lands, but these promises could not attract allies. Firstly, there was no serious force behind the Black Baron. Secondly, the war has already exhausted the same Cossacks, they wanted peace. It is worth noting that if the Wrangels won in an alternative reality, then Russia would face a new collapse. If the Bolsheviks in one way or another led to the restoration of the integrity of the state, then the victory of the White Guards led to a new collapse and colonial position of Russia.

In a desperate search for allies, White even tried to find a common language with Old Man Makhno. But here Wrangel was waiting for complete failure. The peasant leader of New Russia not only executed the Wrangel envoys, but also called on the peasantry to beat the White Guards. Other “green” chieftains in Ukraine willingly made an alliance with the baron, hoping for help with money and weapons, but there was no real power behind them. Negotiations with the leaders of the Crimean Tatars, who dreamed of their statehood, also failed. Some Crimean Tatar activists even suggested that Pilsudsky take Crimea under his own hand, giving the Tatars autonomy.

In May 1920, the Armed Forces of the South of Russia were reorganized into the Russian Army. The Baron hoped to attract not only officers and Cossacks, but also peasants. A broad agrarian reform was conceived for this. Its author was the head of the government of the South of Russia, Alexander Krivoshein, one of Stolypin's most prominent associates and participants in his agrarian reform. Peasants received land by dividing large estates for a fee (five times the average annual crop for a given area, 25-year installment plan was given to pay this amount). A large role in the implementation of the reform was played by volost zemstvos - local governments. The peasants generally supported the reform, but were in no hurry to join the army.

To be continued ...

Information