Formation of the Dnieper and Zaporizhia troops and their service to the Polish-Lithuanian state

The early history of Zaporozhye is also no less stormy, rich and deep than the history of the Volga-Don Perevoloki. Nature has created in this place on the Dnieper a natural barrier to navigation in the form of rapids. No one could overcome the rapids without bringing the ships to the shore to move them around the rapids. Nature itself ordered to have here an outpost, a notch, to whip (at least as you call it) for the protection, defense of the Zaporozhye perevoloki and the Black Sea steppe from the dashing northern boat rote, which constantly sought to raid the Dnieper on the deep rear of the nomads and the Black Sea coast. This intersection on the islands at the rapids probably existed always, because there was always a portage around the rapids. And about this in the history there is evidence. Here is one of the loudest. The mention of the existence of Zaporizhzhya fortifications and garrisons is found in the description of the death of Prince Svyatoslav. In 971, Prince Svyatoslav returned to Kiev from his second and unsuccessful campaign in Bulgaria. After making peace with the Byzantines, Svyatoslav with the remnants of the army left Bulgaria and safely reached the mouth of the Danube. Voevoda Sveneld told him: “Go around the prince on horsebacks, for the Pechenegs are at the doorstep.” But the prince wished to set sail on the Dnieper to Kiev. According to this disagreement, the Russian squad is divided into two parts. One, led by Sveneld, walks through the lands of Russian tributaries, streets and Tivertsi. And the other part, led by Svyatoslav, returns by sea and is ambushed by the Pechenegs. The first attempt of Svyatoslav in the fall of 971 of the year to climb the Dnieper failed, he had to spend the winter in the mouth of the Dnieper, and in the spring of 972 a year to try again. However, the Pechenegs still guarded the rapids. “When spring came, Svyatoslav went to the thresholds. And smoking, the Pechenezh prince, attacked him, and killed Svyatoslav, and took his head, and made a cup from the skull, bound it, and drank from it. Sveneld also came to Kiev to Yaropolk. ”So the dashing Zaporizhzhya Pechenegs, led by their Khan (according to other sources Otaman) Kurei outplayed the famous governor, Svyatoslav was killed, killed and beheaded, and Smoking ordered the head to be made from his head.

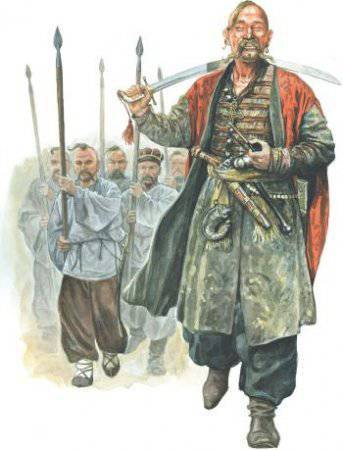

Figure.1 The last battle of Svyatoslav

At the same time, the great warrior, prince (kagan of the Rus) Svyatoslav Igorevich can rightfully be considered one of the founding fathers of the Dnieper Cossacks. Earlier in 965, he, together with the Pechenegs and other steppe peoples, defeated the Khazar Khaganate and conquered the Black Sea steppe. I act in the best traditions of the steppe kagans, part of the Alans and Cherkas, Kasogs or Kaisaks, to protect Kiev from the raids of the steppe people from the south, moved from the North Caucasus to the Dnieper and in Porosye. This decision was promoted by an unexpected and treacherous raid on Kiev by his former Pecheneg allies in 969, when he himself was in the Balkans. On the Dnieper, along with other Turkic-Scythian tribes who had previously arrived and subsequently arrived, mingling with rodents and the local Slavic population, assimilating their language, the settlers formed a special nation, giving it their Cherkasy ethnic name. Until today, this region of Ukraine is called Cherkasy, and the regional center is Cherkasy. Approximately by the middle of the XII century, according to the chronicles around 1146, on the basis of these Cherkas from different steppe peoples, an alliance gradually formed, called the black hoods. Later, already under the Horde, a special Slavic people formed from these Cherkas (black hoods) and then the Dnieper Cossacks were formed from Kiev to Zaporozhye. Svyatoslav himself was fond of the appearance and boldness of the North Caucasian Cherkas and Kaisaks. From early childhood, brought up by the Vikings, nevertheless, under the influence of Cherkas and Kaisaks, he willingly changed his appearance, and most of the later Byzantine chronicles describe him with a long mustache, shaved head and with an olead chubom. More details about the early history of the Cossacks are described in the article "Old Cossack ancestors".

Some historians call the predecessor of the Zaporozhian Sich also the Edisan Horde. This is not the case at the same time. Indeed, in the Horde, to protect against Lithuania, there was a crossing near the Dnieper rapids with a powerful Cossack garrison. Organizationally this fortified area was part of the ulus with the name of the Edisan Horde. But the Lithuanian prince Olgerd defeated her and included in his possessions. The role of Olgerd in the history of the Dnieper Cossacks is also difficult to overestimate. With the disintegration of the Horde, its fragments were in constant hostility between themselves, as well as with Lithuania and with the Moscow State. Even before the final disintegration of the Horde, during the inter-war strife, the Muscovites and Litvins placed part of the Horde lands under their control. Bezachalie and distemper in the Horde were especially remarkable were used by the Lithuanian prince Olgerd. Where by force, where by cleverness and cunning, where, along with the 14 century, he incorporated many Russian princedoms into his domain, including the territories of the Dnieper Cossacks (former black hoods) and set himself broad goals: to do away with Moscow and the Golden Horde. The Dnieper Cossacks were armed forces up to four topics (tumenov) or 40000 well trained and trained troops and proved to be significant support for the policy of Prince Olgerd and from the 14 century begin to play an important role in the history of Lithuania, and as Lithuania was united with Poland and in the history of the Commonwealth. The son and heir of Olgerd, the Lithuanian prince Jagiello, having become the Polish king, founded the new Polish dynasty and made the first attempt through personal union to unite these two states. Later there were several more such attempts and, ultimately, the united kingdom of the Commonwealth was created. At this time, the Don and Dnieper Cossacks were influenced by the same reasons related to the history of the Horde, but there were also features and their fate went in different ways. The territories of the Dnieper Cossacks were the outskirts of the Polish-Lithuanian kingdom, the Cossacks were replenished with the inhabitants of these countries and inevitably gradually strongly “poured and doused”. In addition, the suburban population, the peasantry and the townspeople have long lived on their territory. The Dnieper divided the territory of the Cossacks into right-bank and left-bank parts. The Sloboda population also occupied the territories of the former Kiev principality, Chervonnaya Rus with Lviv, Belarus and the Polotsk Territory adjacent to the Dnieper Cossacks, and when the Horde was in decline, they fell under the rule of Lithuania and then Poland. The nature of the ruling elite of the Dnieper Cossacks was formed under the influence of the Polish "gentry" who did not recognize the supreme power. Shlyakhta was an open class of warring gentlemen, opposing commoners. The true gentleman was ready to die of hunger, but not to disgrace himself by physical labor. Representatives of the nobility differed disobedience, inconstancy, arrogance, arrogance, "ambition" (honor and dignity, from the Latin. honor "honor") and personal courage. Among the gentry, the idea of universal equality within the class (“lords-brothers”) was preserved, and even the king was perceived as equal. In case of disagreement with the authorities, the gentry reserved the right to revolt (rokosh). The above-mentioned gentry habits turned out to be very attractive and infectious for the power elite of the entire Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and so far the relapses of this phenomenon are the most serious problem for stable statehood in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, but especially in Ukraine. This “superfreedom” became a distinctive feature in the ruling elite of the Dnieper Cossacks. They fought an open war against the king, under whose authority they were, if they failed, they came under the rule of the Moscow prince or tsar, the Crimean khan or the Turkish sultan, whom they also did not want to obey. The inconstancy of their caused mistrust to them from all sides, which led to tragic consequences in the future. The Don Cossacks, in relations with Moscow, also often had strained relations, but the edge of reason rarely passed. They never had the desire for treason and, defending their rights and “liberties”, they regularly carried their duties and service in relation to Moscow. As a result of this service in the 15-19 centuries, along the lines of the Don Army, the Russian government formed eight new Cossack regions settled on the borders with Asia.

Fig. 2 Ukrainian Cossack gentry ambition

Despite the difficult relations with the Cossacks in 1506, the Polish king Sigismund I legally assigned to the Cossack community all the land occupied by the Cossacks under the Horde’s rule in the lower reaches of the Dnieper and on the right bank of the river. Formally, free Dnieper Cossacks were run by a royal official, the headmen of Kanevsky and Cherkasy, but they really depended on and conducted their policies very little, and they built relations with their neighbors solely on the balance of power and the nature of personal relations with adjacent rulers. So in 1521, numerous Dnieper Cossacks led by hetman Dashkevich together with the Crimean Tatars went on a campaign against Moscow, and in 1525 the same Dashkevich, also elder Cherkassky and Kanevsky, in response to the treacherous betrayal of the Crimean Khan, he emptied the Cossacks Crimea. Getman Dashkevich had extensive plans to strengthen the statehood of the Hetmanate (the Dnieper Cossacks), including the plan to recreate the Zaporizhzhya Zasek as an advanced outpost in the struggle of the Polish-Lithuanian state with the Crimea, but he did not succeed in implementing this plan.

Again, the Zaporozhye zasek in the post-Ardynsk history in 1556 re-created the Cossack hetman Prince Dmitry Ivanovich Vishnevetsky. This year, part of the Dnieper Cossacks, who did not want to submit to Lithuania and Poland, formed on the Dnieper on the island of Khortytsya a society of single free Cossacks called “Zaporizhian Sich”. Prince Vishnevetsky was descended from the Gediminovich family and was a supporter of the Russian-Lithuanian rapprochement. For this, he was repressed by King Sigismund II and fled to Turkey. Returning after opals from Turkey, with the permission of the king, he became the elder of the ancient Cossack cities of Kanev and Cherkasy. Later he sent ambassadors to Moscow and Tsar Ivan the Terrible accepted him with "kazatstvo" for service, issued a security certificate and sent a salary. Khortytsya was a convenient base for controlling shipping along the Dnieper and raids on the Crimea, Turkey, Carpathian and Danubian principalities. Since the Sich closest to the Dnieper Cossack settlements approached the Tatar possessions, the Turks and Tatars immediately tried to dislodge the Cossacks from Khortitsa. In 1557, the city of Sich withstood a Turkish and Tatar siege, but having fought off the Cossacks, they nevertheless went back to Kanev and Cherkasy. In 1558, the 5 of thousands of blunt Dnieper Cossacks once again occupied the Dnieper Islands right under the nose of the Tatars and Turks. Thus, in the constant struggle for border lands, a community of the most courageous Dnieper Cossacks was formed. The island they occupied became the foremost military camp of the Dnieper Cossacks, where only the single, most desperate Cossacks constantly lived. Hetman Vishnevetsky himself was an unreliable ally of Moscow. By order of Ivan the Terrible, he made a foray into the Caucasus to help the allied Muscovy Kabardians against the Turks and the Nogai. However, after a campaign in Kabarda, he withdrew to the mouth of the Dnieper, fell down with the Polish king and re-entered his service. Vishnevetsky's adventure ended tragically for him. By order of the king, he undertook a campaign in Moldova in order to take the place of the Moldavian ruler, but was treacherously captured and sent to Turkey. There he was sentenced to death and dropped from the fortress tower on iron hooks, which he died in agony, cursing Sultan Suleiman I, who is now widely known to our public thanks to the popular Turkish TV series “The Magnificent Century”. The next hetman, Prince Ruzhinsky, again entered into relations with the Moscow tsar and continued to raid the Crimea and Turkey until his death in 1575.

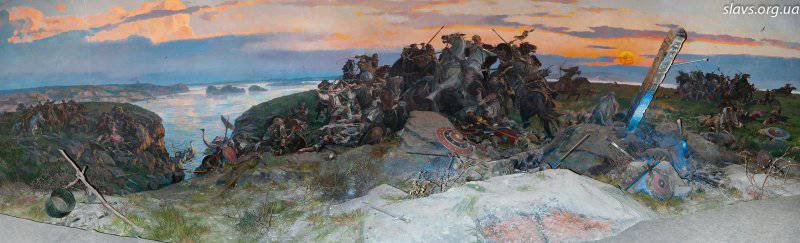

Fig. 3 Terrible Zaporozhye infantry

Since 1559, Lithuania, as part of the Livonian coalition, waged a heavy war with Muscovy over the Baltics. The prolonged Livonian war exhausted and drained Lithuania and weakened in the fight against Moscow so much that, avoiding military-political collapse, she was forced to fully recognize the Union with Poland at 1569 in the Lublin Diet, effectively losing a significant part of sovereignty and losing Ukraine. The new state was called Rzeczpospolita (the republic of both peoples) and headed by its elected Polish king and Sejm. Lithuania had to give up exclusive rights to its Ukraine. Previously, Lithuania did not allow any settlers from Poland here. Now the Poles are eagerly starting the colonization of the newly acquired land. The voivodships of Kiev and Bratslavskoye were founded, where, first of all, crowds of servicemen of the Polish nobility (gentry) with their leaders, high tycoons, rushed. According to the decision of the Seimas, “deserts lying near the Dnieper” should have been settled as soon as possible. The king was authorized to distribute land to deserved nobles for rent or use by office. Polish hetmans, governors, elders and other official tycoons immediately became the lifelong owners of large estates, albeit deserted, but equal in size to specific princedoms. They, in turn, with advantage for themselves distributed them for rent in parts by smaller nobility. Emissaries of new landowners at fairs in Poland, Kholmshchyna, Polesie, Galicia and Volyn announced appeals to a new land. They promised to help with the resettlement, protection from Tatar raids, the abundance of black earth and liberation from all taxes for the period from 20 to 30 the first years. Crowds of multi-tribal Eastern European peasants began to flock to the fat lands of Ukraine, willingly leaving their native places, especially because at that time they were turned from free plowmen into the position of “involuntary servants.” Over the next half century, dozens of new cities and hundreds of settlements have appeared here. New peasant settlements grew like mushrooms on the indigenous lands of the Dnieper Cossacks, where, according to the Khan's decree and royal decrees, the Cossacks had already settled before. Under the Lithuanian authorities in Lubny, Poltava, Mirgorod, Kanev, Cherkasy, Chigirin, Belaya Tserk, only Cossacks were the masters, only elected atamans had the power. Now everywhere were planted Polish elders, who behaved like conquerors, regardless of the customs of the Cossack communities. Therefore, all kinds of troubles began to emerge between the Cossacks and the representatives of the new government: about the right to use the land, about the desire of the elders to turn the entire unserviceable part of the Cossack population into tax and clandestine estates, and most of all because of the violation of old rights and outraged national pride of free people . However, the kings themselves supported the old Lithuanian order. The tradition of elected atamans and hetman, directly subordinate to the king, was not broken. But here the tycoons felt themselves here as “cruels”, “crucians” and in no way limited the gentry subordinate to them. The Cossacks were treated not by the citizens of the Commonwealth, but by the "subjects" of the new lords, as "schismatic mob", flakes, conquered people, fragments of the Horde, behind which, from Tatar times, incomplete bills and offenses for attacks on Poland were drawn. But the Cossacks felt for themselves the natural right of the local indigenous people, did not want to obey the aliens, were outraged by the lawless violations of royal decrees and contempt of the gentry. They did not arouse in them the warm feelings and the crowd of new, mixed tribal settlers, who rushed to their lands along with the Poles. From the peasants who came to Ukraine, the Cossacks kept themselves apart. weapons. The peasants, under all conditions, remained the "subjects" of their lords, the dependent and almost disenfranchised working people, the "cattle". The Cossacks differed from the aliens and their speech. At that time, it had not yet merged with the Ukrainian and differed little from the language of the lower Dontsov. If some other people, Ukrainians, Poles, Litvins (Belarusians) were admitted to the Cossack communities, then these were isolated cases, which were the result of especially cordial relations with local Cossacks or as a result of mixed marriages. New people came to Ukraine voluntarily and "stole" plots in areas that, according to historical tradition and according to royal decrees, belonged to the Cossacks. True, they performed someone else's will, but the Cossacks did not take this into account. They had to make room and watch as their land more and more goes into the wrong hands. The reason is enough to feel dislike for all aliens. Leading a life separate from the newly arrived people, in the second half of the 16th century, the Cossacks began to be divided into four household groups.

The first is Nizovtsy or Zaporozhtsy. They did not recognize any other authority than the Ataman, no extraneous pressure on their will, no interference in their affairs. The people are exclusively military, often unmarried, they served as the first cadres of the continuously growing Cossack population of Zaporizhzhya Niz.

The second is the Hetmanate, on the former Lithuanian Ukraine. The closest to the first group in spirit was a layer of Cossack farmers and cattle breeders. They were already attached to the land and to their occupation, but under new conditions they were sometimes able to speak in the language of rebellion and at some moments left the masses "in their old-aged place, in Zaporogi."

Of these, the third layer stood out - the Cossacks court and registry. They and their families were endowed with special rights, which gave them reason to consider themselves equal with the Polish gentry, although every seedy Polish nobleman treated them haughtily.

The fourth group of social order was a full-fledged gentry, created by the royal privileges of the Cossack serving sergeant. Decades of joint campaigns with the Poles and Litvins showed many Cossacks worthy of the highest praise and reward. They received from the royal hands "privileges" to the gentry rank, along with small estates in the outlying lands. After that, on the basis of "fraternity" with fellow friends, they acquired Polish surnames and coats of arms. From this nobility were selected hetmans with the title "Hetman of His Royal Majesty of the Zaporizhia Army and both sides of the Dnieper". Zaporizhzhya Bottom never obeyed them, although sometimes he acted together. All these events influenced the stratification of the Cossacks, who lived along the Dnieper. Some did not recognize the authorities of the Polish king and defended their independence on the Dnieper rapids, adopting the name "Ground Forces Zaporozhskoe". Part of the Cossacks turned into a free sedentary population engaged in agriculture and cattle breeding. Another part entered the service of the Polish-Lithuanian state.

Fig. 4 Dnieper Cossacks

In the 1575 year, after the death of King Sigismund II on the Polish throne, the Jagiellonian dynasty was interrupted. The warrior Transylvanian prince István Batory, better known in our and Polish history as Stephen Batory, was elected king. Having taken the throne, he set about reorganizing the army. Due to the mercenaries, he raised her fighting capacity and decided to use the Dnieper Cossacks as well. Formerly under the hetman Ruzhinsky, the Dnieper Cossacks were in the service of the Moscow Tsar and defended the borders of the Moscow State. So in one of the raids the Crimean Khan captured up to 11 thousands of Russian people. Ruzhinsky with the Cossacks attacked the Tatars on the way and freed the whole is full. Ruzhinsky made sudden raids not only on the Crimea, but also on the southern coast of Anatolia. Once he landed in Trapezund, then occupied and destroyed Sinop, then he approached Constantinople. From this campaign, he returned with great fame and loot. But in 1575, hetman Ruzhinsky died during the siege of Aslam fortress.

Stefan Batory decided to attract the Dnieper Cossacks to his service, promising them independence and privileges in the internal organization. In 1576, he published the Universal, in which the Cossacks installed the registry in 6000 people. Registered Cossacks were consolidated into 6 regiments, divided into hundreds, neighborhoods and companies. At the head of the regiments was a sergeant, he was given a banner, a horsetail, a seal and a coat of arms. He was appointed a consignment, two judges, a clerk, two captains, troop corps and a horseman, colonels, regimental officers, centurions and atamans. From the environment of the Cossack elite, a commanding foreman stood out, who caught up with the rights of the Polish gentry. The lower Zaporozhye army did not submit to the elder, chose their chieftains. The Cossacks who were not included in the register turned into a tax-paying estate of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and lost their Cossack position. Some of these Cossacks did not obey the Universal and went to the Zaporizhian Sich. Later, at the head of the regiment regiments, a Cossack chief began to be selected - hetman of his royal majesty, the Zaporizhia Army and both sides of the Dnieper. The king appointed Chigirin, the ancient capital of chigov (jig), one of the Black Klobuk tribes, to be the main city of the registered Cossacks. A salary was assigned, with the shelves was land ownership, which was given to the rank or rank. Zaporozhtsy king established Kosovo ataman.

Having reformed the armed forces, in 1578, Stefan Batory resumed hostilities against Moscow. To protect themselves from the Crimea and Turkey, Batory forbade the Dnieper Cossacks to attack their lands, indicating to them the raids - Moscow lands. In this war of Poland with Russia, the Dnieper and Zaporozhye Cossacks were on the side of Poland, were part of the Polish troops, made raids and carried out destruction and pogroms no less brutal than the Crimean Tatars. Batory was very pleased with their activities and praised for the raids. At the time of the resumption of hostilities with Poland, Russian troops controlled the Baltic coast from Narva to Riga. In the war with Batory, Moscow troops began to suffer big failures and leave occupied territories. There were several reasons for the failures:

- depletion of the military resources of a country waging war for more than 20 years.

- the need to divert large resources to maintain order in the newly conquered areas of Kazan and Astrakhan, the Volga peoples constantly rebelled.

- constant military tension in the south due to the threat from the Crimea, Turkey and the nomadic hordes.

- the continuous and merciless struggle of the king against the princes, the boyars and internal treason.

- great dignity and talent of Stefan Batory as an effective military and political leader of that time.

- a large moral and material assistance to the anti-Russian coalition from Western Europe.

The war of many years has exhausted the forces of both sides, and in 1682, the Yam-Zapolsky peace was concluded. With the end of the Livonian war, the Dnieper and Zaporizhzhya Cossacks began to make attacks on the Crimea and the Turkish possessions. This created the threat of a war between Poland and Turkey. But Poland, no less than Muscovy, was exhausted by the Livonian War and did not want a new war. King Stephen Batory openly fought with the Cossacks, when they attacked the Tatars and Turks in violation of the royal decrees. Such he ordered "to seize and forge."

And the next king, Sigismund III, took even more decisive measures against the Cossacks, which allowed him to conclude an "eternal peace" with Turkey. But this completely contradicted the main vector of the then European policy directed against Turkey. At this time, the Austrian emperor created another union to expel the Turks from Europe, and invited Muscovy to this union. For this, he promised Russia Crimea and even Constantinople, and asked 8-9 thousands of Cossacks "hardy in hunger, useful for seizing booty, for devastating the enemy country and for sudden raids ...". Seeking support in the fight against the Polish king, Turks and Tatars, the lower-level Cossacks often turned to the Russian tsar and formally recognized themselves as his subjects. So, in 1594, when the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation hired the Cossacks to his service, they sought permission from the Russian tsar. The tsarist government tried to maintain appropriate relations with the Cossacks, especially with those who lived in the upper reaches of the Donets and protected Russian lands from the Tatars. But there was no great hope for the Zaporozhian Cossacks, and the Russian ambassadors always “visited”, “whether the sovereign would be direct” these “subjects”.

After the death of Stephen Batory in the 1586 year, the efforts of the gentry to the Polish throne raised King Sigismund III from the Swedish dynasty. The magnates were his opponents and advocated for the Austrian dynasty. A “rokosh” began in the country, but Chancellor Zamoysky defeated the troops of the Austrian challenger and his supporters. Sigismund entrenched on the throne. But the royal power in Poland by the efforts of the gentry was reduced to a complete dependence on the decisions of the general assembly, where each pan had veto power. Sigismund was a supporter of absolute monarchy and an ardent Catholic. By this he placed himself in hostile relations with the Orthodox magnates and the population, as well as with the gentry - supporters of democratic privileges. A new “rokosh” began, but Sigismund coped with it. The magnates and gentry, fearing the king's revenge, moved into the neighboring countries, above all in the troubled Muscovy at that time. The activities of these Polish-Lithuanian insurgents in the Moscow domains did not have special national and state goals, except robbery and profit. About these peripetias of the Time of Troubles and about the participation of Cossacks and gentry in it was described in the article “Cossacks in Time of Troubles”. During the rokosha, Russian insurgents, opponents of militant Catholicism adopted by Sigismund, acted along with the Polish opponents of the king. And Mr. Sapega even called on the Russian militia to join the Polish rokosh and to overthrow Sigismund, but negotiations on this topic did not lead to positive results.

And on the distant outskirts of the Commonwealth, in Ukraine, Polish magnates and their surroundings relied little on even the rights of the privileged sections of Cossack society. Land grabs, repressions, rudeness and disregard for the indigenous people of the region, the frequent violence of the incoming troops and the administration annoyed all the Cossacks. Anger grew every day. The aggravation of relations between the Dnieper Cossacks and the central government occurred in 1590, when Chancellor Zamoyskiy subordinated the Cossacks to the Crown Hetman. This violated the ancient right of the Cossack hetmans to appeal directly to the first person, the king, tsar or khan. One of the main reasons for the hostile attitude of the Dnieper Cossacks to Poland was the beginning religious struggle of Catholics against the Orthodox Russian population, but especially from 1596, after the Brest Church Union, i.e. another attempt to merge the Catholic and Eastern churches, as a result of which part of the Eastern Church recognized the authority of the Pope and the Vatican. A population that did not recognize Union was deprived of the right to occupy positions in the Polish kingdom. The Russian Orthodox population was faced with a choice: either to adopt Catholicism or start a struggle to protect their religious rights. The center of the struggle began was the Cossacks. With the strengthening of Poland, the Cossacks also underwent the intervention of the kings and the Sejm in their internal affairs. But it was not easy for Poland to forcefully turn the Russian population into Uniates. Constant persecution of the Orthodox faith and Sigismund’s measures against the Cossacks led to the Cossacks revolting against Poland in 1591. The first hetman to raise a rebellion against Poland was Krishtof Kosinsky. Significant Polish forces were sent against the rebel Cossacks. The Cossacks were defeated, and Kosinsky was captured and executed in 1593. After that, Nalyvayko became the hetman. But he also fought not only with the Crimea and Moldova, but also with Poland and in 1595, when returning from a raid on Poland, his troops were surrounded by hetman Zolkiewski and defeated. Further relations between the Cossacks and the Polish-Lithuanian state assumed the character of a protracted religious war. But for almost half a century, protests did not grow into the elements of a general uprising and were expressed only in individual explosions. Cossacks were busy with campaigns and wars. In the early years of the seventeenth century, they took an active part "in the restoration of the rights" of the alleged prince Dimitri to the throne of Moscow. In 1614 was with Hetman Konashevich Sagaidachny Cossacks reached the shores of Asia Minor and turned the city of Sinop into ashes, in 1615, Trabzon was burned, visited the outskirts of Istanbul, and many Turkish warships were burned and sank in the arms of the Danube and near Ochakov. In 1618 was with King Vladislav went under Moscow and helped Poland to get Smolensk, Chernihiv and Novgorod Seversky. And then the Dnieper Cossacks provided generous military assistance and service to the Polish-Lithuanian state. Once in November 1620 the Turks defeated the Poles under Tsetseru, and the hetman of Zolkiewski was killed, the Seimas turned to the Cossacks, calling them to march on the Turks. The Cossacks did not have to beg for a long time; they went to sea and, with attacks on the Turkish coast, delayed the advancement of the Sultan's army. Then, together with the Poles 47, thousands of Dnieper Cossacks took part in the defense of the camp near Hotin. This was a significant help, because against 300 thousands of Turks and Tatars, Poland had only 65 thousands of warriors. Having met stubborn resistance, the Turks agreed to negotiations and lifted the siege, but the Cossacks lost Sagaidachny, who died of injuries on 10 on April 1622. After such assistance, the Cossacks considered themselves entitled to receive the promised salary with a special surcharge for Hotin. But the commission appointed to consider their claims, instead of surcharges, decided to reduce the registry again, and the Polish magnates intensified the repression. A significant part of demobilized after reducing the register of "dischargers" went to Zaporozhye. The hetmans chosen by them did not submit to anyone and made raids on the Crimea, Turkey, the Danube principalities and Poland. But in November 1625 they were defeated at Krylov and were forced to accept the hetman appointed by the king. The registries were left in the 6000 ranks, the Cossack farmers had to either reconcile with the panschin or leave their plots, leaving them in possession of the new owners. For the new registry, only people of proven loyalty were selected. What are the others?

Fig.5 Rebellious spirit of Maidan

At this time, the Cossacks intervened in the Crimean-Turkish relations. Khan Shahin Giray wanted to secede from Turkey and asked the assistance of the Cossacks. Spring 1628 the Cossacks went to the Crimea with ataman Ivan Kulag. A part of the Cossacks from Ukraine, led by hetman Mikhail Doroshenko, joined them. Having pogroms under Bakhchisarai of the Turks and their supporter Janibek Girey, they moved to Cafu. But at this time, their ally Shagin Giray reconciled with the enemy and the Cossacks had to hastily retreat from the Crimea, and Hetman Doroshenko fell near Bakhchisarai. Instead, the king appointed Gregory Chorny to be the hetman of the submissive to him. This unquestioningly fulfilled all the demands of the magnates, oppressed the lower brotherhood of the Cossacks, did not prevent to subordinate them to the elders and the gentlemen. The Cossacks were leaving the masses from Ukraine to Bottom, and therefore the population of the Sichev lands was greatly multiplied in his time. Under hetman Chorny, the gap between the hetman and the intensified Niz became especially brewing, since Bottom appealed to an independent republic, and Cossack Ukraine was getting closer and closer connected with the Commonwealth. The royal protege was not to the liking of the masses. Zaporozhye Cossacks moved from the thresholds to the north, captured Chorny, tried him for corruption and penchant for union, and condemned the execution. Shortly thereafter, the Nizovtsy under the command of Koshevoy, the ataman Taras Shaked, attacked the Polish camp near the Alta River, occupied it and destroyed the troops standing there. The 1630 uprising began, attracting many registrants to their side. It ended in the battle of Pereyaslav, which, according to the Polish chronicler Pyasetsky, the Poles "cost more victims than the Prussian war." They had to make concessions: the registry was allowed to increase to eight thousand, and the Cossacks from Ukraine were guaranteed impunity for participating in the uprising, but these decisions were not executed by the magnates and gentry. From now on, Bottom is increasingly growing at the expense of the Cossack farmers. A part of the foremen goes to Sich, but on the other hand, many accept the whole order of life from the Polish gentry and turn into loyal Polish nobles. In 1632, the Polish king Sigismund III died. His long reign passed under the sign of compulsory expansion of the influence of the Catholic Church, with the support of supporters of the church union. On the throne came his son Vladislav IV. In 1633-34 years 5-6 th. Registered Cossacks took part in campaigns to Moscow. For several years thereafter, a particularly intensive resettlement of peasants from the west to Ukraine continued. It was 1638 grew to thousands of new settlements, planned by the French engineer Boplan. He also led the construction of the Polish fortress Kudak at the first Dnieper threshold and in place of the old Cossack settlement of the same name. Although in August 1635, the Cossacks with ataman Sulima or Suleiman took Kudak off the raid and destroyed a garrison of foreign mercenaries in it, but after two months they had to give it to the loyal king registrants. In 1637 was protection of the Cossack population of Ukraine, constrained by new settlers, again tried to take over Zaporizhzhya Bottom. Cossacks came to the "parish" led by chieftains Pavlyuk, Skidan and Dmitry Guney. They were joined by local Cossacks from Kanev, Stebliev, and Korsun, who were and were not in the register. About ten thousand of them gathered, but after the defeat at Kumayki and Moshny, they had to retreat to the lands of Sich. Soon the Poles suppressed the Cossack movement on the Left Bank, which began next year with Ostryanin and Guna. Judging by the small number of participants (8-10 th. people), Cossack speeches were conducted by the Zaporozhian Cossacks alone. The thinness of their movements and the organization of defense in the camps show the same thing. At this time, the old and new Ukrainian population of the steppe was occupied by setting up hundreds of new settlements under the supervision of the troops of the crown hetman S. Konetspolskogo. In general, in those years, attempts to combat cooperation with the Ukrainians ended for the Zaporozhye Cossacks discord and quarrels, reaching up to mutual murders. But the fugitive peasants Nizovaya Republic accepted willingly. They could engage in free and peaceful labor on the land allocated to them. A layer of "subjects of the Zaporozhyan Lower Army" gradually replenished the ranks of farmers and servants. Some Ukrainian peasants who wanted to continue the armed struggle, accumulated on the shores of the Southern Bug. On the river Teshlyk they founded their own separate Teshlyk Sich.

After the defeats of 1638, the rebels returned to Bottom, and in Ukraine, instead of the registrants who had gone, new Cossacks were recruited. Now the register consisted of six regiments (Pereyaslavsky, Kanevsky, Cherkassky, Belotserkovsky, Korsunsky, Chigirinsky) with a thousand people each. The commanders of the regiments were appointed from the noble gentry, and the rest of the ranks: the regimental captains, captains and below them were elected ex officio. The post of hetman was abolished and his post was replaced by the appointed Commissioner Peter Komarovsky. The Cossacks had to swear allegiance to the Commonwealth, promise obedience to the local Polish authorities, not to go to Sich and not to take part in sea voyages of Nizovtsev. Not entered in the register and living in Ukraine remained "subjects" of the local gentry. Resolutions of the "Final Commission with the Cossacks" were also signed by representatives of the Cossacks. Among others was the signature of the Military Clerk Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Ten years later, he will lead the new struggle of the Cossacks against Poland and his name will thunder to the whole world.

Figure.6 Polish gentry and armored Cossack

The situation was aggravated by the fact that a part of the Ukrainian magnates and gentry not only adopted Catholicism, but also began to demand it from their subjects in various ways. So many pans confiscated local churches and rented them to small townships — artisans, taverns, taverns, wineries and distillers — and they began to pay a fee from villagers and Cossacks for the right to pray. These and other Jesuit measures overflowed with patience. In response, the Cossacks of the Hetmanate united with the Cossacks of the Ground Forces of Zaporizhia and a general uprising began. The struggle continued for more than a decade and ended with the accession of the Hetmanate to Russia in the 1654 year on the Pereyaslav Rada. But this is a completely different and very complicated story.

http://topwar.ru/22250-davnie-kazachi-predki.html

http://topwar.ru/27541-starshinstvo-obrazovanie-i-stanovlenie-donskogo-kazachego-voyska-na-moskovskoy-sluzhbe.html

http://topwar.ru/31291-azovskoe-sidenie-i-perehod-donskogo-voyska-na-moskovskuyu-sluzhbu.html

http://topwar.ru/26133-kazaki-v-smutnoe-vremya.html

topwar.ru

Gordeev A.A. History of the Cossacks

Istorija.o.kazakakh.zaporozhskikh.kak.onye.izdrevle.zachalisja.1851.

Letopisnoe.povestvovanie.o.Malojj.Rossii.i.ejo.narode.i.kazakakh.voobshhe.1847. A. Rigelman

Information