Cossacks in Time of Troubles

At the beginning of the XVII century in Russia, events occurred, called contemporaries the Troubles. This name was not given by chance. A real civil war broke out in the country at that time, complicated by the intervention of Polish and Swedish feudal lords. Smoot began in the reign of Tsar Boris Godunov (1598-1605), and began to complete in 1613, when Mikhail Romanov was elected to the throne. Great troubles, whether in England, France, the Netherlands, China or other countries are described and investigated in great detail. If we discard the temporal and national palette and specificity, then the same scenario remains, as if they were all created for a carbon copy.

1. a) - In the first act of this tragedy a merciless struggle for power unfolds between the various groups of the aristocracy and the oligarchy.

b) - In parallel, a great contusion of the minds of a considerable part of the educated classes takes place and great bedlam settle in their brains. Called this bedlam can be different. For example, the Church Reformation, Enlightenment, Renaissance, Socialism, the Struggle for Independence, Democratization, Acceleration, Perestroika, Modernization or otherwise, it does not matter. Anyway this is a contusion. The great Russian analyst and merciless preparator of Russian reality, F.M. Dostoevsky called this phenomenon in his own way - "devilry."

c) - At the same time, “well-wishers” from contiguous geopolitical rivals begin to sponsor and support fugitive oligarchs and officials, as well as creators of new and subversive old pillars and “defining generators” of the most destructive, irrational and counterproductive ideas. There is a creation and accumulation of pernicious entropy in society. Many experts want to see exclusively foreign orders in distemper and the facts in many respects indicate this. It is known that the unrest in the Spanish Netherlands, the terrible European Reformation and the Great French Revolution are the British projects, the struggle for the independence of the North American colonies is a French project, and Napoleon Bonaparte is rightly considered the godfather of all Latin American independence. If he did not crush the Spanish and Portuguese metropolises, did not produce a massive emission of revolutionaries in their colonies, Latin America would have gained independence not earlier than Asia and Africa. But to absolutize this factor is to cast a shadow on the fence. Without valid internal causes, Smoot does not exist.

2. However, the first act of this tragedy can last for decades and have no consequences. To move to the second act of the play you need a good reason. The reason can be anything. Unsuccessful or protracted war, famine, crop failure, economic crisis, epidemic, natural disaster, natural disaster, termination of the dynasty, the emergence of an impostor, an attempted coup, the killing of a reputable leader, electoral fraud, increased taxes, the abolition of benefits, etc. Drovishki already prepared, you only need to bring the paper and strike the match. If the power is komolay, and the opposition is quick, then it will certainly take advantage of the pretext and make a coup, which will then be called a revolution.

3. If the constructive part of the opposition in the course of the coup curbs the destructive part, then on the second act everything will end (as it happened in the 1991 year). But often it happens the other way around and a bloody civil war begins with monstrous victims and consequences for the state and the people. And very often all this is accompanied and burdened by foreign military intervention. The great troubles are different from others in that they have all three acts, and sometimes more and drag on for decades. No exception and Russian distemper of the beginning of the XVII century. During 1598-1614, the country was shaken by numerous uprisings, riots, conspiracies, coups, revolts, it was tormented by adventurers, invaders, rogues and robbers. Cossack historian A.A. Gordeev counted in this unrest four periods.

1. Dynastic struggle between the boyars and Godunov in 1598-1604.

2. The struggle between Godunov and Dimitri, which ended in the death of the Godunovs and Dimitri, 1604-1606

3. The struggle of the lower classes against the boyar rule of 1606-1609

4. The struggle against external forces that seized power in Muscovite Rus'.

Historian Solovyov saw the cause of the Troubles in the "bad moral state of society and too developed Cossacks." Without arguing with the classic in essence, it should be noted that the Cossacks in the first period did not accept any participation at all, but joined the Troubles with Dimitri in 1604 year. Therefore, the long-term undercover struggle between the boyars and Godunov in this article is not considered as having no relation to its subject. Many prominent historians see the causes of the Troubles in the politics of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Catholic Roman Curia. And indeed, at the beginning of the 17th century. a certain person who pretended to be the miracle of the rescued Tsarevich Dmitry (the most well-established version that he was a fugitive monk Grigory Otrepyev), appeared in Poland, having previously visited the Zaporozhye Cossacks and learned from them military matters. In Poland, this False Dmitry was the first to declare to Prince Adam Vishnevetsky of his claims to the Russian throne.

Objectively, Poland was interested in the Time of Troubles, and the Cossacks were dissatisfied with Godunov, but if the reasons were only in these forces, then to overthrow the legitimate royal power, they were insignificant. The king and Polish politicians sympathized with the emerging Troubles, but refrained from open intervention for the time being. Poland’s position was far from favorable, it was in a protracted war with Sweden and could not take the risk of war with Russia. The true idea of the Troubles was in the hands of the Russian-Lithuanian part of the aristocracy of the Commonwealth, to which the Livonian aristocracy adjoined. As part of this aristocracy there were many nobles "fleeing the wrath of Grozny." The three surnames of the Western Russian oligarchs were the main instigators and organizers of this intrigue: Belarusian Catholic and Minsk voivod Prince Mnishek, who had recently changed Orthodoxy Belarusian (then they were called Litvin) magnates Sapieha and, embarked on the path of polishing, the family of Ukrainian magnates Prince Vishnevets. The center of the conspiracy was Sambir Prince Mnishek castle. The formation of volunteer squads took place there, magnificent balls were organized, to which the fluent Moscow nobility was invited and the recognition of the “legitimate” heir to the Moscow throne. A court aristocracy was formed around Demetrius. But in this environment only one person believed in his real royal origin - he himself. The aristocracy needed him only to overthrow Godunov. But whatever forces took part in the emerging confusion, it would not have such disastrous and destructive consequences if Russian society and people did not have very deep roots of discontent caused by the policies and rule of Boris Godunov. Many contemporaries and descendants noted the intelligence and even the wisdom of Tsar Boris. Thus, Prince Katyrev-Rostovsky, who did not like Godunov, wrote nonetheless: “My husband is very wonderful, his mind is happy and sweet-talking, his velm is blessed and impoverished, and earnestly earnest ...” and so on. Similar opinions sometimes sound today. But with this it is impossible to agree. The classic separation of the smart from the wise says: “A smart person comes out very worthy of all the unpleasant situations in which he falls, but the wise ... simply does not get into these unpleasant situations”. Godunov, on the other hand, was the author or co-author of many ambushes and traps, which he skillfully built up to his opponents and into which he himself later succeeded. So on the wise he does not pull. Yes, and smart too. He responded to many of the challenges of his time with measures that led to hatred of broad sections of society, both in his address and in the address of the royal power. The unprecedented discredit of the royal power led to a catastrophic Distemper, the indelible guilt for which lies with Tsar Boris. However, everything is in order.

1. Tsar Boris was very fond of external effects, window dressing and props. But the ideological emptiness, formed in the consciousness of the people around the non-royal origin of Godunov, who unjustly occupied the throne, could not be filled with any external forms, attributes, and his personal qualities. The conviction that the occupation of the throne was achieved by mercenary means and that whatever he did, including for the benefit of the people, was firmly rooted among the people, the people saw in this only a selfish desire to strengthen the throne of the Moscow kings. The rumor that existed among the people, Boris was known. To stop the hostile rumors, denunciations were widely used, many people slandered, and blood poured. But popular rumor did not fill with blood, the more blood flowed, the more rumors hostile to Boris spread. Rumors caused new denunciations. The priests on ponomares, the abbess on bishops, serfs on gentlemen, wives on husbands, children on fathers and vice versa, were reported to each other and foe. Denunciations became public contagion, and scammers were generously encouraged by Godunov at the expense of the state, officials and property of the repressed. This promotion produced a terrible effect. Moral decline affected all sectors of society, representatives of noble families, princes, Rurik's descendants reported on each other. It was in this "bad moral state of society ..." that the historian Solovyov saw the cause of the Troubles.

2. In Moscow Rus, land tenure before Godunov was local, but not ordinary, and the peasants who worked on the land could leave the landowner every spring on St. George's Day. After the Volga took possession, the people moved to new open spaces and left the old lands without working hands. To stop leaving, Godunov issued a decree forbidding the peasants to leave the previous owners and attached the peasants to the land. Then the saying was born: "Here's your grandmother and St. George's Day." Moreover, 24 of November 1597 of the year issued a decree on “years of age”, according to which peasants who had fled from the masters “to this ... year in five years” were to be searched, tried and returned “back to where everyone lived”. By these decrees, Godunov summoned the fierce hatred of the entire peasant masses.

3. It seemed that nature itself rebelled against the power of Godunov. In 1601, in the summer there were long rains, and then the early frosts struck and, according to a contemporary, “beat strong all the work of human deeds in the fields”. The following year, crop failure repeated. The country began a famine that lasted three years. The price of bread increased 100 times. Boris forbade selling bread more than a certain limit, even resorting to the persecution of those who inflated prices, but did not achieve success. In 1601 — 1602 Godunov even went for the temporary restoration of the St. George's Day. Mass hunger and dissatisfaction with the establishment of the “lesson years” caused a major uprising led by the Cotton in 1602 — 1603, a harbinger of the Troubles.

4. Frankly hostile attitude towards Godunov was also on the part of the Cossacks. He rudely interfered in their inner life and constantly threatened them with annihilation. The Cossacks did not see these repressive measures of state expediency, but only the demands of the “bad king not the royal root” and gradually embarked on the path of struggle against the “unreal” king. The first information about Tsarevich Dimitrii Godunov received precisely from the Cossacks. In 1604, the Cossacks captured on the Volga Seeds Godunov, who was on a mission to Astrakhan, but identifying an important person, released him, but with an order: "Tell Boris that we will be with Prince Dimitry soon." Knowing the hostile attitude of the south-eastern Cossacks (Don, Volga, Yaik, Terek) to Godunov, the Pretender sent his messenger with a letter to send ambassadors to him. Having received the diploma, the Don Cossacks sent ambassadors to him with atamans Ivan Korela and Mikhail Mezhakov. Returning to Don, the envoys confirmed that Dimitri was indeed a prince. The Donets mounted their horses and moved to the aid of Dimitri, originally in the number of 2000 people. So began the Cossack movement against Godunov.

But not only hostile feelings were towards Boris - he found the right support among a significant part of the servants and merchants. He was known as a fan of everything foreign, and with him there were many foreigners, and for the sake of the king, "many old men brady their compatriots ...". This impressed a certain part of the educated strata of society and settled in the souls of many of them the pernicious virus of servility, flattery and admiration for foreignness, this indispensable and infectious companion of any distemper. Godunov, like Grozny, sought to form a middle class, service and merchant, and in him wanted to have the support of the throne. But even now the role and significance of this class is greatly exaggerated, primarily because of the arrogance of this class itself. And at that time this class was still in its infancy and could not resist the classes of the aristocracy and the peasantry that were hostile to Godunov.

In Poland, there were also changes favorable for the Impostor. In this country, the royal power was constantly under the threat of rebellion of regional magnates and always sought to channel the rebellious spirit of the regionals in directions opposite to Krakow and Warsaw. Chancellor Zamoyski still considered Mnishek’s venture with Dimitri to be a dangerous adventure and did not support it. But King Sigismund, under the influence and at the request of the Vyshnevetsky and Sapieha, after long delays, gave a private audience to Dimitry and Mnishek and blessed them to fight for the Moscow throne ... as a private initiative. However, he promised money, which however, did not give.

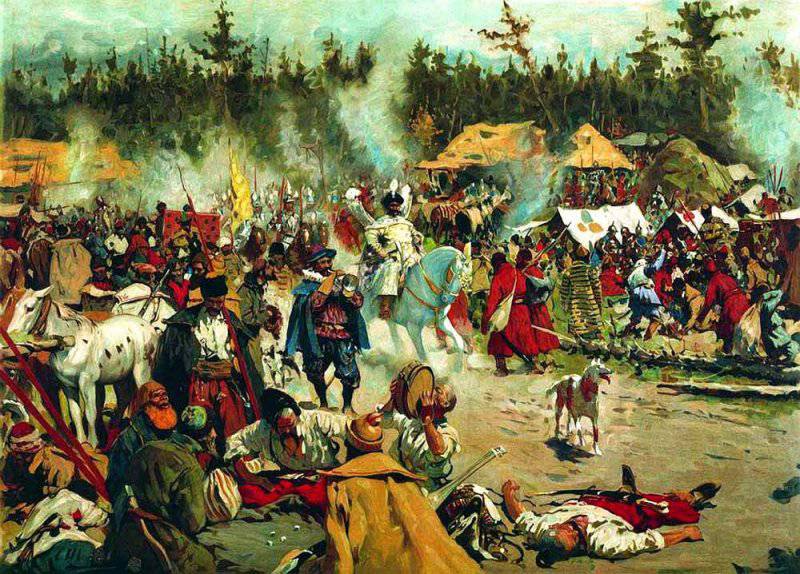

After the presentation to the king, Dimitri and Mnishek returned to Sambir and in April 1604 began preparations for the march. The forces gathered in Sambor amounted to about one and a half thousand people and with them Dimitri moved towards Kiev. Near Kiev, 2000 of the Don Cossacks joined him, and with these troops, in the fall, he entered the Moscow domain. At the same time, from Don 8000, the Don, Volga and Terek Cossacks went to the north by the “Crimean” road. Having entered the lands of Moscow, Dimitri in the first cities met with people's sympathy and the cities switched sides without resistance. However, Novgorod-Seversky, occupied by Basman’s archers, resisted and stopped the Pretender’s movement to the north. In Moscow, began to collect troops, which were assigned to Prince Mstislavsky. 40 rati was collected from thousands of people against 15 thousand from the Pretender. Dimitri was forced to retreat and in Moscow it was perceived as a strong defeat of the enemy. Indeed, the position of the rebels was taking a bad turn. Sapieha wrote to Mnishek that in Warsaw they look badly at his enterprise and advise him to return. Mnishek at the request of the Sejm began to gather in Poland, the troops began to demand money, but he did not have them. Many fled and Dimitri left no more than 1500 people, who instead of Mnishek elected Hetman Dvorzhitsky. Dimitri went to Sevsk. But at the same time, the rapid and extremely successful movement of Cossacks in the east to Moscow continued, the cities surrendered without resistance. Pali Putivl, Rylsk, Belgorod, Valuyki, Oskol, Voronezh. Streltsy regiments scattered around the cities did not offer any resistance to the Cossacks, since in their essence they continued to remain Cossacks. Smoot showed that the artillery regiments during anarchy turned into Cossack troops and under their former name participated in the coming civil war of “all with all” from various sides. In Sevsk, 12 of thousands of Zaporizhzhya Cossacks, who had not previously participated in the movement, came to Dimitry. Having received support, Dimitri moved east to join up with the southeastern Cossacks. But in January 1605, the royal troops defeated the Pretender. The Cossacks fled to Ukraine, Dimitri to Putivl. He decided to give up the fight and return to Poland. But 4 thousands of Don Cossacks arrived to him and persuaded him to continue the fight. At the same time, the Donians continued to take cities in the east. The Kroms were occupied by a detachment of the Don Cossacks in 600, a man with chieftain Korela at the head. After the victory in January, the voivods of Godunov retreated to Rylsk and were inactive, however, prompted by the king, they marched towards Kromy with a large army headed by the boyars Shuisky, Miloslavsky, Golitsyn. The siege of Krom was the final act of the struggle between Godunov and Dimitri and ended with a break in the psychology of the boyars and troops in favor of Dimitri. The siege of Krom 80 000 by the army during 600 Cossack defenders led by Ataman Korela lasted about 2's months. Contemporaries marveled at the exploits of the Cossacks and "the deeds of boyars like laughter." The besiegers showed such negligence that in Kromy, the besieged, in broad daylight with a wagon train, reinforcements from 4000 Cossacks entered. In the army of the besiegers, diseases and mortality began, and on April XIInx of Tsar Boris himself was hit and after 13 hours he died. After his death, Moscow quietly swore Fedor Godunov, his mother and family. Their first step was a change of command in the army. Arriving at the front, the new commander of the voivode Basmanov saw that most of the boyars did not want the Godunovs, and if he resisted the general mood, it meant going to certain death. He joined the Golitsyn and Saltykov and announced the army that Dimitri was a real prince. Shelves without resistance proclaimed him king. The army moved to the Eagle, the Pretender went to the same place. In Moscow, he continuously sent messengers to excite the people. Prince Shuisky announced to the crowd gathered near the Kremlin that the prince was saved from the murderers, and they buried another in his place. The crowd broke into the Kremlin .... The Godunovs were finished. Dimitri was at that time in Tula, and after the coup a noble from Moscow gathered there, hurrying to declare her loyalty. The ataman of the Don Cossacks, Smaga Chesmensky, who was admitted to the reception with a clear preference for others, also arrived. 20 June 1605 of the year Dimitri triumphantly entered Moscow. Ahead of all were the Poles, then the archers, then the boyars, and then the king, accompanied by the Cossacks. 30 June 1605 was celebrated in the Assumption Cathedral in the kingdom. The new king generously rewarded the Cossacks and dismissed them home. Thus ended the struggle between Godunov and the Impostor. Godunov was defeated not because of lack of troops or lost battles, all material possibilities were on the side of Godunov, but solely because of the psychological state of the masses.

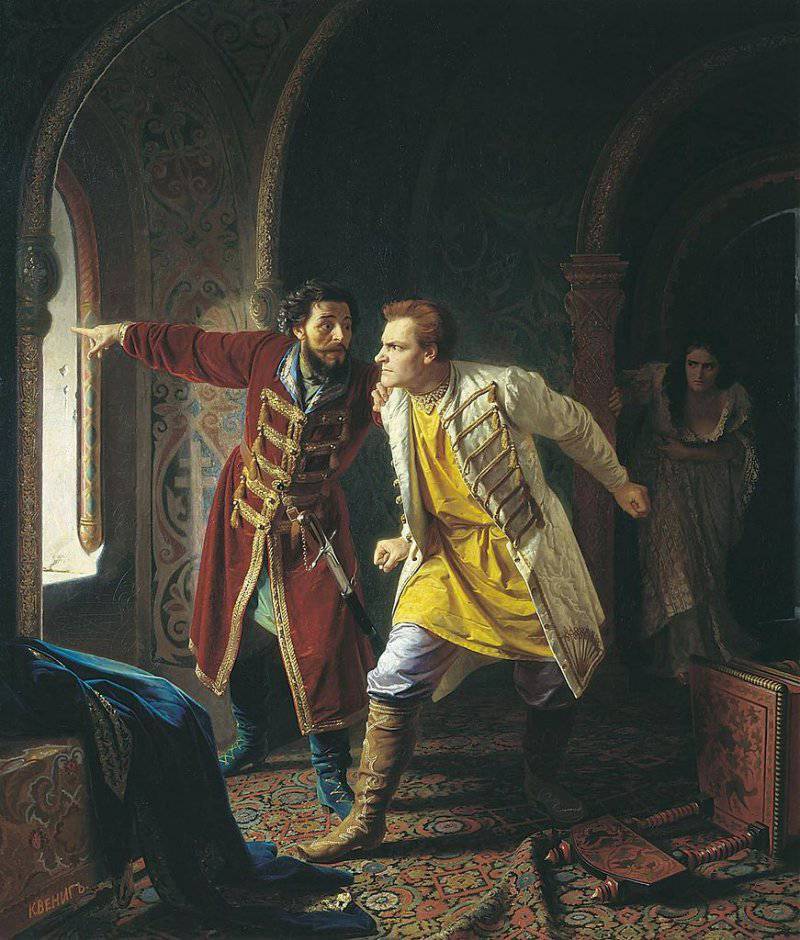

The beginning reign of Dimitri was unusual. He walked freely through the streets, talked to the people, received complaints, went to the workshops, examined the products and guns, tried their quality and shot accurately, went out to fight with the bear and hit him. This simplicity was popular with the people. But in foreign policy, Dimitri was strongly bound by his commitments. His movement was launched in Poland, and the forces that had assisted him had their own goals and sought to gain their own benefit. With Poland and Rome, he was strongly bound by his obligations to marry a Catholic Marina Mnishek, to give her Novgorod and Pskov lands as a dowry, Poland to cede Novgorod-Seversky and Smolensk, to allow Roman curia to build unlimited Catholic churches in Russia. In addition, many Poles appeared in Moscow. They noisily walked, insulted and bullied people. The behavior of the Poles served as the main reason for the excitement of popular discontent against Dimitri. 3 May 1606, with great magnificence, Marina Mniszek entered Moscow, a huge retinue housed in the Kremlin. May 8 began wedding fun, the Russians were not allowed on them, except for a small number of guests. The enemies of Dimitri took advantage of this, the Golitsyn and Kurakina entered into a conspiracy with the Shuisky. Through their agents, they spread rumors that Dimitri “did not observe the king”, did not observe Russian customs, rarely went to church, would not resonate with outraged Poles, would marry a Catholic ... etc. Dissatisfaction with the policy of Dimitri began to manifest itself in Poland, as he retreated from fulfilling many of his previous commitments and eliminated all hopes of reuniting churches. On the night of May 17, 1606, detachments of conspirators occupied the Kremlin’s 12 gate and struck the alarm. Shuisky, having a sword in one hand, and in the other a cross said to those around him: "In the name of God, go to the evil heretic" and the crowd went to the palace .... With the death of Dimitri, the third period of the Troubles began - a popular rebellion arose.

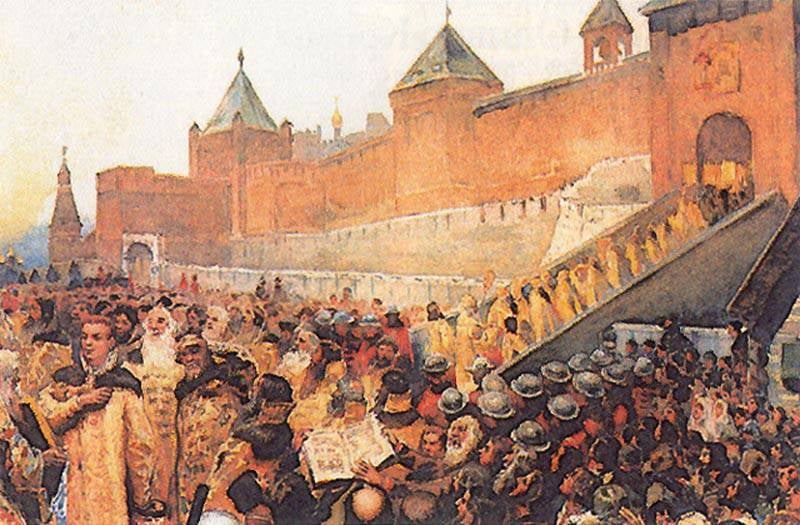

The conspiracy and murder of Demetrius was the result of the activity of the boyar aristocracy and made a painful impression on the people. And already on May 19, people gathered on Red Square and began to demand: "who killed the king?" The boyars who were in the conspiracy went to the square and proved to the people that Demetrius was an impostor. Gathered in Red Square by the boyars and the crowd, Shuisky was elected king and was crowned king on June 1. The goals of Shuisky were determined at the very beginning of his reign. The boyars who did not participate in the conspiracy were repressed, the power of the conspirator boyars was established in the country, but almost immediately a resistance movement began against the new government. The uprising against Shuisky, as well as against Godunov, began in the northern cities. In Chernigov and Putivl were exiled princes Shakhovskaya and Telatevsky. Shakhovskoy began to spread rumors that Dimitri was alive and found a person similar to him. The new impostor (a certain Molchanov) left for Poland and settled in the Sambir castle with his stepmother Marina Mniszek. The reprisals in Moscow against the Poles and the taking of more than 500 people hostage together with Marina and Jerzy Mniszeky caused great irritation in Poland. But there was another rebellion in the country, the Rokosh, and although it was soon suppressed, the king had no desire to get involved in a new Moscow rebellion. The appearance of a new Demetrius frightened Shuisky, too, and he sent troops to the Seversky lands. However, the new False Dmitry was in no hurry to go to war and continued to live in Sambir. Ivan Bolotnikov, a former servant of Prince Telatevsky, appeared to him. He was still a youth captured by the Tatars and sold to Turkey. As a slave in the galleys, he was freed by the Venetians and headed to Russia. Passing through Poland, he met an impostor, was fascinated by the new Demetrius, and was sent by him to the governor in Putivl to Shakhovsky. The appearance of the sweet-spoken and energetic Bolotnikov in the camp of the rebels gave a new impetus to the movement. Shakhovsky gave him a detachment of 12 thousand people and sent to Kromy. Bolotnikov began to act in the name of Demetrius, skillfully praised him. But at the same time, his movement began to take on a revolutionary character, he openly took the position of liberating the peasants from the landowners. AT historical literature, this rebellion is called the first peasant war. Shuisky sent the army of Prince Trubetskoy to the Kroms, but it fled. The path was open and Bolotnikov set off for Moscow. He was joined by detachments of children of the boyar Istoma Pashkov, Ryazan squads of the nobles Lyapunovs and Cossacks. There was a rumor among the people that Tsar Demetrius did just that in order to turn everything around in Russia: the rich should get poorer, and the poor should get rich. The rebellion grew like a snowball. In mid-October 1606, the rebels approached Moscow and began to prepare for the assault. But the revolutionary nature of the peasant army of Bolotnikov pushed the nobles away from her and they moved on to Shuisky, followed by the children of the boyars and archers. Muscovites sent a delegation to the camp of Bolotnikov demanding to show Demetrius, but he was not there, which caused people to distrust his existence. The rebellious spirit began to subside. November 26, Bolotnikov decided to storm, but suffered a complete defeat and moved to Kaluga. After that, the Cossacks also went over to Shuisky and were forgiven. The siege of Kaluga lasted all winter, but to no avail. Bolotnikov demanded the arrival of Demetrius in the troops, but he, having provided himself financially, renounced his role and was blissful in Poland. Meanwhile, another imposter appeared in Putivl - Tsarevich Pyotr Fedorovich - the imaginary son of Tsar Fedor, who introduced an additional split and confusion into the ranks of the rebels. Having endured the siege in Kaluga, Bolotnikov moved to Tula, where he also successfully defended himself. But in the army of Shuisky there was a sapper-cunning man who, having built rafts across the river, covered them with earth. When the rafts sank, the water in the river rose and went along the streets. The rebels surrendered to Shuisky’s promise to have mercy on everyone. He broke the promise and all prisoners were subjected to terrible reprisals, they were drowned. However, the Time of Troubles did not end there, her terrible destructive potential was not yet exhausted, she took new forms.

In the south, meanwhile, a new Lzhedmitry appeared, under its banner all the layers opposed to the boyars stretched and the Cossacks turned on again. Unlike the previous one, this impostor did not hide in Sambor, but immediately arrived at the front. The identity of the second False Dmitry is even less known than other impostors. First he was recognized by the Cossack ataman Zarutsky, then by the Polish governors and hetmans Makhovetsky, Vatslavsky and Tyszkiewicz, then by the governor Khmelevsky and Prince Adam Vishnevetsky. At this stage, the Poles took an active part in the Troubles. After the suppression of internal unrest, or rokosh, in Poland many people were threatened with the king's revenge and they went to Moscow lands. Pan Roman Rozhinsky led the troops to the False Smith 4000, he was joined by a detachment of Pan Makhovetsky and 3000 Cossacks. Pan Rozhinsky was elected hetman.

Earlier, the chieftain Zarutsky went to the Volga and brought the 5000 Cossacks. Shuisky by that time was already hated by the whole country. After the victory over Bolotnikov, he married a young princess, enjoyed his family life and did not think about public affairs. Numerous royal army came out against the rebels, but it was cruelly defeated near Bolokhov. The impostor moved to Moscow, the people everywhere met him with bread and salt and bell ringing. Rozhinsky's troops approached Moscow, but they did not manage to capture the city on the move. They camped in Tushino, blockading Moscow. To the Poles continuously arrived replenishment. From the west arrived Pan Sapieha with the detachment. South of Moscow, Pan Lisovsky collected the remnants of the defeated army of Bolotnikov and occupied Kolomna, then Yaroslavl. Yaroslavl Metropolitan Philaret Romanov was taken to Tushino, an impostor received him with honor and made him a patriarch. Many of the nobles ran from Moscow to the False Dmitry II and made up with him a whole royal court, which was actually led by the new patriarch Philaret. And Zarutsky also received the boyar rank and commanded all the Cossacks in the Pretender's army. But the Cossacks not only fought with the troops of Vasily Shuisky. Not having a normal supply, they robbed the population. Many robber gangs adjoined the forces of the Pretender and declared themselves Cossacks. Although Sapieha with the Cossacks long and unsuccessfully stormed the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, but he managed to spread his troops up to the Volga, and the Dnieper Cossacks were outraged in the land of Vladimir. In total, under the Tushino command, up to 20 thousands of Poles gathered with the Dnieper, up to 30 thousands of Russian rebels and up to 15 thousands of Cossacks. In order to improve relations with official Poland, Shuisky released hostages with guards from Moscow, including Jerzy and Marina Mniszek, from Moscow, but they were seized by Tushinois along the way. The treaties of Moscow and Warsaw had no meaning for the Tushino people. To raise the prestige of the second False Dmitry, his entourage decided to use the wife of the first False Dmitry, Marina Mnishek. After some altercations, delays and caprices, she was persuaded to recognize the new Pretender as her husband, Dimitri, without marital duties.

The Swedish king, meanwhile, offered Shuisky assistance in the fight against the Poles and, under the contract, singled out a detachment in 5 of thousands of people under the command of Delagardi. The detachment was replenished with Russian warriors and, under the general leadership of Prince Skopin-Shuisky, set about clearing the northern lands and began to drive the rebels into Tushino. According to the agreement between Moscow and Poland, Sigismund also had to withdraw Polish troops from Tushino. But Rozhinsky and Sapieha did not submit to the king and demanded a million zlotys from the king for leaving 1. These events began the fourth, last period of the Troubles.

Sweden's intervention in Moscow affairs gave Poland a reason to enter the war with Russia and in the autumn of 1609, Sigismund laid siege to Smolensk. The performance of Poland against Moscow made a complete regrouping of the internal forces of the Russian people and changed the goals of the struggle, and from that time the struggle began to assume a national liberation character. The beginning of the war changed the position of the “Tushino”. Sigismund, having entered the war with Russia, had the goal of conquering it and occupying the throne of Moscow. He sent an order to Tushino to Polish troops to go to Smolensk and end the Pretender. But Rozhinsky, Sapieha and others saw that the king was encroaching on the country they had conquered and refused to obey him and "liquidate" the Pretender. Seeing the danger, the Pretender with the Mnisheks and the Cossacks went to Kaluga, but his court, headed by Filaret Romanov, did not follow him. At that time, the virus of lizoblyudstva and admiration for foreigners had not yet been overcome, and they turned to Sigismund with a proposal that he release his son Vladislav to the Moscow throne, subject to their acceptance of Orthodoxy. Sigismund agreed and an embassy from 42 of noble boyars was sent to him. Philaret Romanov and Prince Golitsyn, one of the contenders for the Moscow throne, entered this embassy. But near Smolensk, the embassy was captured by the troops of Shuisky and sent to Moscow. Shuisky, however, forgave the Tushins, and they "in gratitude" among the boyars began to broaden and multiply the idea of overthrowing Shuisky and recognizing Vladislav as a king. Meanwhile, Skopin-Shuisky's troops were approaching Moscow, the Poles withdrew from Tushino, and the siege of Moscow on 12 in March on 1610 ended. During the festivities in Moscow on this occasion, Skopin-Shuisky suddenly fell ill and died. The suspicion of poisoning a popular warlord in the country fell again on the king. For the further struggle against the Poles, large Russian-Swedish forces led by Tsar's brother Dimitri Shuisky were sent near Smolensk, but on the march they were suddenly attacked by hetman Zolkiewski and utterly defeated. The consequences were terrible. The remnants of the troops fled and did not return to Moscow, the Swedes partly surrendered to the Poles, partly went to Novgorod. Moscow remained defenseless. Shuisky was dethrone and forcibly tonsured as a monk.

Zolkiewski moved to Moscow, and the Cossacks of Zarutsky and the Pretender from Kaluga headed there. A government of seven boyars led by Mstislavsky was urgently formed in Moscow. It entered into negotiations with Zolkiewski about the urgent sending of Prince Vladislav to Moscow. After reaching an agreement, Moscow swore allegiance to Vladislav, and Zolkiewski attacked Zarutsky’s Cossacks and forced them to return to Kaluga. Soon the Pretender was killed by his own allies, the Tatars. Zolkiewski occupied Moscow, and to Sigismund the boyars equipped a new embassy headed by Filaret and Golitsyn. But Sigismund decided that Moscow had already been conquered by his troops and it was time for him to become the Tsar of Moscow himself. Zolkiewski, seeing such deception and substitution, resigned and left for Poland, taking the Shuisky brothers with him as a trophy. His successor, Pan Gonsevsky, crushed the seven-boyars and established a military dictatorship in Moscow. The Boyar embassy, arriving in Smolensk, also saw the deception of Sigismund and sent a secret message to Moscow. On its basis, the patriarch Hermogenes issued a letter, sent it around the country and called on the people to militia against the Poles. The candidacy of an Orthodox and militant Catholic, the persecutor of Orthodoxy, who was Sigismund, did not suit anyone. The Ryazanians, led by Prokopy Lyapunov, were the first to respond, and the Don and Volga Cossacks Trubetskoy standing in Tula and the “new” Cossacks of Zarutsky standing in Kaluga joined them. At the head of the militia stood the Zemstvo government, or Triumvirate, consisting of Lyapunov, Trubetskoy and Zarutsky. At the beginning of 1611, the militia approached Moscow. Pan Gonsevsky knew about the movement that had begun and was preparing for defense, under his command there were up to 30 thousands of troops.

The Poles occupied the Kremlin and China Town, they could not defend all of Moscow and decided to burn it out. But this attempt led to the revolt of the Muscovites, which increased the power of the militia. And in the very militia began friction between the nobles and the Cossacks. Nobles, led by Lyapunov, tried to limit Cossack freedoms through decrees of the Zemstvo government. Projects of repressive anticorruption decrees were stolen by Polish agents and delivered to the Cossacks. Lyapunov was summoned to the Circle for explanations, tried to escape to Ryazan, but was captured and hacked with sabers on the Circle. After the murder of Lyapunov, most of the nobles left the militia, in Moscow and the country there was no Russian government power, only the occupation. In addition to political differences between the Cossacks and the zemstvos there was another disturbing circumstance. In the camp of the Cossacks under Ataman Zarutsky was Marina Mnishek, who considered herself the legitimate crowned queen, she had a son, Ivan, whom many Cossacks considered to be the legitimate heir. In the eyes of the zemstvo this was “Cossack theft”. The Cossacks continued the siege of Moscow and in September 1611 of the year occupied China Town. Only the Kremlin remained in the hands of the Poles, famine began there. Meanwhile, Sigismund finally took Smolensk by storm, but having no money to continue the campaign, he returned to Poland. A Sejm was convened to which noble Russian captives were represented, including the brothers Shuisky, Golitsyn, Romanov, Shein. The Sejm decided to send assistance to Moscow led by Hetman Chodkiewicz.

In October, Khodkiewicz approached Moscow with a huge train and attacked the Cossacks, but could not break into the Kremlin and withdrew to Volokolamsk. At this time a new impostor appeared in Pskov and a split occurred among the Cossacks. The Cossacks of Trubetskoy left Zarutsky’s Cossack Homage, who recognized the new impostor and set up a separate camp, continuing the siege of the Kremlin. The Poles, taking advantage of discord, again occupied China Town, while Chodkiewicz, with the help of Russian collaborators, transported several carts to the besieged. The Nizhny Novgorod militia of Minin and Pozharsky was in no hurry to Moscow. It reached Yaroslavl and stopped waiting for the Kazan militia. Pozharsky decisively avoided uniting with the Cossacks - his goal was to elect a king without the participation of the Cossacks. From Yaroslavl the leaders of the militia sent letters, calling for elected people from the cities to elect a legitimate sovereign. At the same time, they corresponded with the Swedish king and the Austrian emperor, asking their hereditary princes for the Moscow throne. Elder Abrahamy went to Yaroslavl from Lavra with a reproach to them that if Chodkiewicz used to “come to Moscow, then in vain will your work be even worse.” After that, Pozharsky and Minin, after thorough reconnaissance, moved to Moscow and set up a separate camp from the Cossacks. The arrival of the second militia produced a final split among the Cossacks.

In June, 1612, Zarutsky with the “thieving Cossacks” was forced to flee to Kolomna, in Moscow only Don and Volga Cossacks remained under the command of Prince Trubetskoy. At the end of the summer, having received a new wagon train and reinforcements from Poland, Pan Chodkiewicz moved to Moscow in a detachment of which, in addition to the Poles and Litvin, there were up to 4-x thousand Dnieper Cossacks headed by Hetman Shiryay. Behind him was a huge train, which was supposed to, by all means, break through to the Kremlin and save the besieged garrison from starvation. The Pozharsky militia took up positions near the Novodevichy Monastery, the Cossacks occupied Zamoskvorechye and strongly strengthened it. The main attack Chodkiewicz directed against the militias. The battle lasted all day, all attacks were repulsed, but the militia was pressed and heavily drained of blood. By the end of the battle, contrary to Trubetskoy’s decision, Ataman Mezhakov with a part of the Cossacks attacked the Poles and prevented their breakthrough to the Kremlin. A day later, Hetman Chodkiewicz went ahead with carts and baggage. The main blow this time fell on the Cossacks. The battle was "a great and terrible thing ...". In the morning, the Zaporozhye infantry, with a powerful attack, knocked the Cossacks out of the front ditches, but after sustaining huge losses, it could not advance further. At noon, a skillful maneuver Cossacks cut off and captured most of the convoy. Chodkiewicz realized that everything was lost. The purpose for which he came is not achieved. The Lithuanians with a part of the convoy departed from Moscow, the Polish hussars who had broken into the Kremlin without a convoy only exacerbated the situation of the besieged. The victory over Khodkevich reconciled Pozharsky with Trubetskoy, but not for long. This happened because in the militia the nobles received a good salary, the Cossacks did nothing. The old breeder of the troubled prince Shakhovskoy arrived in the Cossack camp, returning from exile, and began to resent the Cossacks against the militia. Cossacks began to threaten to beat and rob the nobles.

The conflict settled Laurus from their means. 15 September 1612, Pozharsky presented an ultimatum to the Poles, which they arrogantly rejected. October 22 Cossacks went on the attack, retaken China-town and drove the Poles into the Kremlin. The hunger in the Kremlin intensified and October Poles 24, because they did not want to surrender to the Cossacks, they sent ambassadors to the militia with the request that no prisoner be killed by the sword. They were given a promise and on the same day the boyars and other Russian collaborators, who were under siege, were released from the Kremlin. The Cossacks wanted to kill them, but they were not allowed. The next day, the Poles opened the gate, folded weapon and waited for their fate. The prisoners were divided between the militia and the Cossacks. The part that came to Pozharsky survived and then went on to exchange the Great Embassy in Poland. The Cossacks did not survive and killed almost all of their prisoners. The property of the prisoners went to the treasury, and by order of Minin was sent to pay the Cossacks. To do this, the Cossacks were a census, they turned 11 thousands, the militia consisted of 3500 people. After the occupation of Moscow and the departure of Khodkevich, the central part of Russia was cleared of the Poles. But in the southern and western regions, their gangs and Cossacks wandered. The Dnieper Cossacks, who had left Khodkevich, headed north, occupied and plundered Vologda and Dvinsk lands. In the land of Ryazan, Zarutsky stood with his liberta and gathered wandering people into his detachments. The power of the “Marching Duma” was established in Moscow — the Cossacks and the boyars, who were faced with the most important task — the election of a legitimate tsar. But for this most important business, the Moscow camp represented the greatest “turmoil”.

Notable boyars and governors quarreled among themselves, the Cossacks with Zemsky continued discord. Poland intervened in the question of succession to the throne. Sigismund, realizing the failure of his claims, sent a letter in which he apologized and reported that Vladislav was not healthy and this prevented him from arriving in Moscow at the proper time. Sigismund with his son and army arrived in Vyazma, but none of the Moscow people showed up to pay homage to them and with the onset of cold weather and the fall of the Kremlin these candidates departed to Poland. The pernicious foreign-born virus slowly left the Russian body. By December 1612, the first congress of the Council gathered in Moscow, but after long disputes and disagreements, it parted, not having come to any agreement. The second congress in February also did not come to an agreement. The question of electing a sovereign was discussed not only by the Council, but even more so between the armed parts of the militia and the Cossacks. The Cossacks, contrary to Pozharsky, did not want to have a foreigner on the Moscow throne. Among the Russians, princes and boyars could be contenders: Golitsyn, Trubetskoy, Vorotynsky, Pozharsky, Shuisky and Mikhail Romanov. Each applicant had many supporters and irreconcilable opponents, and the Cossacks insisted on the election of young Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. After many strife and fights, most agreed on the compromise figure of Mikhail Romanov, who was not tainted by any links with the interventionists. The significant role of the Cossacks in the liberation of Moscow predetermined their active participation and decisive role in the Zemsky Sobor of 1613 of the year at which they elected the king. According to the legend, the Cossack chieftain at the Council submitted a certificate of election as the tsar of Mikhail Romanov, and on top of it he laid his naked saber. When the Poles learned about Mikhail Romanov’s choice by the tsar, hetman Sapega, in whose house Filaret Romanov lived “in captivity,” announced to him: “... your son was put on the throne by the Cossacks.” Delagardi, who ruled Novgorod in the Swedes occupied by Novgorod, wrote to his king: “Tsar Mikhail is seated on the throne with Cossack sabers”. In March, the Embassy of 49 people arrived in March at the Ipatiev Monastery, where nun Martha and her son were located. 3 Ataman, 4 Esaula and 20 Cossacks. After some hesitation, preconditions and coaxing 11 July 1613, Michael was crowned king. With the election of the king, Smoot did not end, but only proceeded to its completion.

Riots did not subside in the country and new ones rose. Poles, Lithuanians and Lithuanians were outraged in the west, the Dnieper Cossacks, led by Sagaidachny in the south. Cossacks joined Zarutsky and made devastation no less cruel than the Crimeans. On the eve of the summer of 1613, the wife of two False Dmitriyas Marina Mnishek appears on the Volga, with her son ("vorenk", as the Russian chronicle calls him). And with her - the chieftain Ivan Zarutsky with the Don and Zaporozhye Cossacks, driven out by the troops of the Moscow government from near Ryazan. They managed to capture Astrakhan and kill the governor Khvorostinin. Having gathered up 30 000 of military people - Volga freemen, Tatars and legs Zarutsky went up the Volga to Moscow. Prince Dmitry Lopata-Pozharsky led the fight against Zarutsky and Mnishek. Relying on Kazan and Samara, he sent ataman Onisimov to the Volga free Cossacks, urging them to recognize Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. As a result of the negotiations, most of the Volga Cossacks left Zarutsky, considerably undermining his strength. In the spring of 1614, Zarutsky and Mnishek expected to go on the offensive. But the arrival of Prince Oboevsky's big rati and the Lopaty-Pozharsky offensive forced them to leave Astrakhan themselves and flee to Yaik on Bear Island. From there they hoped to strike at Samara. But the Yaik Cossacks, seeing all the futility of their position, by agreement, issued in June 1614, Zarutsky and Mnishek with the “vorenkom” to the Moscow authorities. Ivan Zarutsky was impaled, the “vorenok” was hanged, and Marina Mnishek soon died in prison. The defeat in 1614 of the "Hulev" Ataman Trenéus and a number of other small groups showed the Cossacks the only way for him - serving the Russian state, although after that relapses of "freemen" still happened ...

Russia came out of the Troubles, having lost the population of 7 million people from 14, who were under Godunov. Then the saying was born: "Moscow burned out from a penny candle." Indeed, the fire of troubled times began from a spark taken from the center of a dying legitimate dynasty, brought to the borders of Russia by a person who is still not known to history. The troubles that raged for a decade and claimed half of the population ended in the restoration of the interrupted monarchy. All layers of the population, from princes to slaves inclusive, were drawn into the struggle of “all with all”. Everyone wanted and sought to derive their benefits from the Time of Troubles, but in its fire all strata were defeated and suffered enormous losses and sacrifices, because they set themselves goals exclusively personal and private, rather than national. The foreigners did not win in this fight either; all foreign collaborators and sponsors of the Time of Troubles were subsequently brutally punished by Rus and reduced to the level of secondary European states or destroyed. It was after analyzing the Time of Troubles and its consequences that the Ambassador of Prussia in Petersburg Otto von Bismarck uttered: “Do not hope that once you take advantage of Russia's weakness, you will receive dividends forever. Russians always come for their money. And when they come - do not rely on the Jesuit agreements that you have signed, supposedly justifying you. They are not worth the paper on which they are written. Therefore, it’s worth playing with the Russians honestly or not at all. ”

After the Troubles, the state organism and the social life of the Moscow State were completely changed. The unit princes, the sovereign nobility and their guards finally switched to the role of the service state class. Muscovite Rus turned into a whole organism, the power in which belonged to the tsar and the dummy boyars, their rule was determined by the formula: "the king ordered, the Duma decided". Russia rose on that state path, which the peoples of many European countries were already following. But the price for it was paid completely inadequate.

*****

At the beginning of the XVII century. finally, a type of Cossack was formed — a universal warrior, equally capable of participating in sea and river raids, fighting on land both in horse and on foot, knowing perfectly well fortification, siege, mine and subversive activities. But the main type of fighting then was sea and river raids. Most of the time, the Cossacks became horsemen later under Peter I, after the ban on going to sea in 1696. At its core, the Cossacks are a caste of warriors, kshatriyas (in India, a caste of warriors and kings), who for centuries defended the Orthodox Faith and the Russian Land. The feats of the Cossacks Russia became a powerful empire. Ermak presented Ivan the Terrible Siberian Khanate. Siberian and Far Eastern lands along the rivers Ob, Yenisei, Lena, Amur, also Chukotka, Kamchatka, Central Asia, and the Caucasus were joined largely due to the military valor of the Cossacks. Cossack ataman (hetman) Bogdan Khmelnytsky reunited Ukraine with Russia. But the Cossacks often spoke out against the central government (their role in the Russian Troubles, in the uprisings of Razin, Bulavin and Pugachev is remarkable). Many and stubbornly Dnieper Cossacks rebelled in the Commonwealth.

This was largely due to the fact that the ancestors of the Cossacks were ideologically brought up in the Horde on the laws of Yasa of Genghis Khan, according to which only Chingizid could be the real king, i.e. a descendant of Genghis Khan. All other rulers, including Rurikovich, Gediminovich, Piast, Jagiellonian, Romanovs and others, were insufficiently legitimate in their eyes, were “not real kings”, and the Cossacks were morally and physically allowed to participate in their overthrow, reign, rebellion and other anti-government activities. And after the Great Zamyatni in the Horde, when hundreds of Chingizids, including Cossack sabers, were destroyed during the strife and power struggles, and the Genghisides lost Cossack piety. One should not overlook the simple desire to show off, take advantage of the weakness of power and take a legitimate and rich trophy during the unrest. Papal ambassador to the Sich Father Pirling, who had worked hard and successfully to send the warlike fervor of the Cossacks to the lands of the heretics Muscovites and Ottomans, wrote this in his memoirs: This feather left its trail of blood. For the Cossacks, it was customary to deliver the thrones to all kinds of applicants. In Moldova and Wallachia periodically resorted to their help. For the formidable freemen of Dnepr and Don it was completely indifferent, genuine or imaginary rights belong to the hero of the minute.

For them it was important one thing - that their share of good production. But was it possible to compare the poor Danube principalities with the boundless plains of the Russian land, full of fabulous wealth? ”However, from the end of the 18th century until the October Revolution, the Cossacks unconditionally and diligently played the role of defenders of the Russian statehood and the support of the royal power, having received from revolutionaries even the nickname satrapov. By some miracle, the German queen and her outstanding grandees, a combination of reasonable reforms and punitive actions, managed to drive into the riotous Cossack head the steady idea that Catherine II and her descendants were “real” kings. This metamorphosis in the consciousness of the Cossacks, which occurred at the end of the 18th century, is in fact Cossack historians and writers still little studied and studied. But there is an immutable fact, from the end of the XVIII century and before the October Revolution, the Cossack riots disappeared like a hand.

Information sources:

http://topwar.ru/21371-sibirskaya-kazachya-epopeya.html

Gordeev A.A. History of the Cossacks

Information