Siberian Cossack Epic

After the terrible Siberian khan Kuchum, one of the royal descendants of Genghis Khan, was knocked down from a kuren by a handful of simple Cossacks, an unprecedented, impetuous, grandiose movement eastward into Siberia began. In just half a century, the Russian people made their way to the Pacific coast. Thousands of people walked "meet the sun" through mountain ranges and impassable swamps, through impassable forests and immense tundra, making their way through sea ice and rapids. Yermak struck the wall like a breach in the wall, holding back the pressure of the colossal forces that had awakened among the people. Gangs of people eager for freedom, harsh but endlessly enduring and bravely courageous, rushed to Siberia.

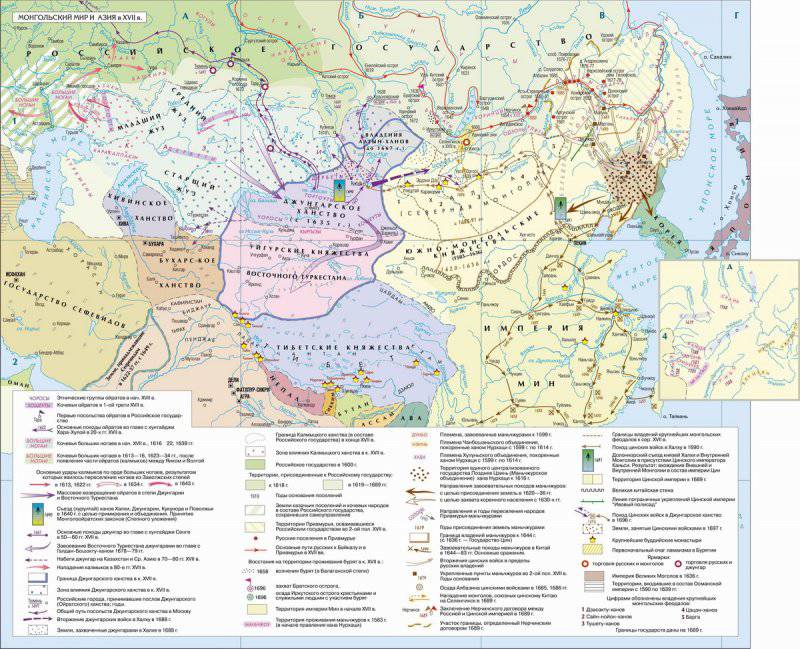

It was incredibly difficult to move across the gloomy expanses of Northern Asia with its wild, harsh nature, with a rare, but very militant population. All the way from the Urals to the Pacific Ocean is marked by numerous unknown graves of explorers and sailors. But the Russian people stubbornly went to Siberia, pushing further and further east to the limits of their homeland, transforming this desert and gloomy land with their work. Great feat of these people. For one century, they have three times increased the territory of the Russian state and laid the foundation for everything that gives and will give us Siberia. Now Siberia is called the part of Asia from the Urals to the mountain ranges of the Okhotsk coast, from the Arctic Ocean to the Mongolian and Kazakh steppes. In the 17th century, the concept of Siberia was more significant and included not only the Ural and Far Eastern lands, but also a significant part of Central Asia.

Coming out into the expanses of North Asia, the Russian people entered a country that had long been settled. True, it was inhabited extremely unevenly and weakly. By the end of the XVI century on the square in 10 million square meters. km lived only 200-220 thousand people. It is not numerous, scattered throughout the taiga and tundra, the population had its ancient and complex history, was very different in language, economic structure and social development.

By the time the Russians came, the only people who had their own statehood were the Tatars of the Kuchum kingdom defeated by Yermak, some ethnic groups had patriarchal-feudal relations. Most of the Siberian peoples, Russian Cossack land explorers found at various stages of patriarchal-tribal relations.

By the time the Russians came, the only people who had their own statehood were the Tatars of the Kuchum kingdom defeated by Yermak, some ethnic groups had patriarchal-feudal relations. Most of the Siberian peoples, Russian Cossack land explorers found at various stages of patriarchal-tribal relations.The events of the end of the XVI century proved to be crucial in the historical fate of North Asia. The “Kuchum Kingdom”, which closed the closest and most convenient way deep into Siberia, crumbled in 1582 from the daring blow of a small group of Cossacks. Nothing could change the course of events: neither the death of the "Siberian conquistador" Yermak, nor the departure of the remnants of his squad from the capital of the Siberian Khanate, or the temporary accession of the Tatar rulers in Kashlyk. However, only government troops were able to successfully complete the work begun by free Cossacks. The Moscow government, realizing that Siberia cannot be mastered by a single blow, proceeds to its tried and tested tactics. Its essence was to consolidate on a new territory, building cities there, and, relying on them, gradually move forward. This “offensive cities” strategy soon yielded brilliant results. From 1585, the Russians continued to oppress the indomitable Kuchum and, having founded many cities, until the end of the 16th century, conquered Western Siberia.

In the 20-s of the XVII century, the Russian people came to the Yenisei. Began a new page - the conquest of Eastern Siberia. From the Yenisei into the depths of Eastern Siberia, Russian explorers advanced rapidly.

In the 1627 year, the 40 Cossacks, led by Maxim Perfilyev, reached Ylim on Upper Tunguska (Angara), took a yasak from the neighboring Buryats and Evenks, housed a cabin, and a year later returned to the Yeniseisk steppe, pushing a new expedition to the north-east. In 1628, Vasily Bugor went to Ilim with 10 Cossacks. There was built Ilimsky burg, an important stronghold for further advance on the Lena River.

Rumors about the wealth of the Lena lands began to attract people from the most distant places. So, from Tomsk to Lena in 1636, a detachment in 50 was equipped with a man led by ataman Dmitry Kopylov. These service people, having overcome unheard of difficulties, in 1639, the first of the Russian people came to the expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

In 1641, the Cossack foreman Mikhail Stadukhin, having equipped the detachment at his own expense, went from Oimyakon down to the mouth of the Indigirka, and then sailed by sea to Kolyma, securing its connection by building a strong point for new campaigns. A detachment of Cossacks from 13, left in prison, led by Semyon Dezhnev, withstood a brutal attack of the Yukagir army numbering more than 500 people. Following this, the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev took part in the events that immortalized his name. In June, 1648, a hundred Cossacks on 7 Kochi, came out of the mouth of the Kolyma in search of new lands. Sailing to the east, overcoming inhuman difficulties, they circled the Chukchi Peninsula and entered the Pacific Ocean, proving the existence of a strait between Asia and America. After that Dezhnev founded the Anadyr fortress.

Having reached the natural limits of the Eurasian continent, the Russian people turned south, which allowed them to quickly master the rich lands of the Okhotsk coast and then go to Kamchatka. In 50, the Cossacks came to Okhotsk, founded earlier by a detachment of Semyon Shelkovnik who had come from Yakutsk.

Another route for the development of Eastern Siberia was the southern route, which became increasingly important after the Russians consolidated in the Baikal region, attracting the main stream of immigrants. The beginning of the accession of these lands was laid in the construction of the Verkholensky fortress in 1641. In the 1643-1647 years, with the efforts of atamans Kurbat Ivanov and Vasily Kolesnikov, most of the Baikal Buryats took Russian citizenship and the Verkhneangarsky prison was built. In subsequent years, the Cossack detachments went to Shilka and Selenga, founding Irgen and Shilka jails, and then another chain of fortresses. The rapid accession of this land to Russia was promoted by the aspiration of the indigenous people to rely on Russian fortresses in the fight against the raids of the Mongol feudal lords. During these years, a well-equipped detachment led by Vasily Poyarkov made his way to Amur and descended to the sea, clarifying the political situation in the Daur land. Rumors about the rich lands of Poyarkov spread throughout Eastern Siberia and shook hundreds of new people. In 1650, a squad led by ataman Yerofey Khabarov reached Amur, and being there 3 of the year became the winner of all clashes with the local population and defeated a thousand Manchu detachment. The general result of the actions of the Khabarovsk army was the accession of the Amur region to Russia and the beginning of the mass migration of the Russian people there. Following the Cossacks, already in the 50 of the 17th century, industrialists and peasants rushed to Amur, who soon formed the majority of the Russian population. By the 80 years, despite its foreign position, the Amur region was the most populated in the whole of Transbaikalia. However, further development of the Amur lands was impossible due to the aggressive actions of the Manchu feudal lords. Small Russian troops, with the support of the Buryat and Tungus populations, more than once defeated the Manchus and the Mongols allied with them. The forces, however, were too unequal, and according to the terms of the Nerchinsk peace treaty of 1689, the Russians, defending the Trans-Baikal region, were forced to leave part of the developed territories in the Amur region. The possessions of the Moscow sovereign on the Amur were now limited only to the upper tributaries of the river.

At the end of the 17th century, the beginning of the accession to Russia of new vast lands in the northern regions of the Far East was laid. In the winter of 1697, a detachment led by Cossack Pentecostal Vladimir Atlasov set off from Anadyr fortress on Kamchatka to Kamchatka. The hike continued on 3 of the year. During this time, the detachment traveled hundreds of kilometers across Kamchatka, defeating a number of tribal and tribal associations that had resisted it and founded the Verkhnekamchatsky fortress.

In general, by this time, Russian explorers had collected reliable information on virtually all of Siberia. Where, on the eve of “Yermakov take”, European cartographers could only bring out the word “Tartary” began to draw the real outlines of a giant continent. The history of world geographical discoveries did not know such a huge scale, such speed and energy in the study of new countries.

Most of the Siberian taiga and tundra, the small Cossack detachments passed without encountering serious resistance. Moreover, the locals supplied the Cossack detachments the main contingent of guides to new lands. This was one of the main reasons for the phenomenally fast movement of explorers from the Urals to the Pacific Ocean. Successful advance to the east was favored by the extensive river network of Siberia, which allowed it to move up the Pacific Ocean from one river basin to another. But overcoming the portages presented great difficulties. This required several days and it was a way “through great mud, swamps and small rivers, and in other places there is dragging and mountains, and the forests are dark everywhere”. For transporting goods, except for people, only pack horses and dogs could be used, “while using carts through the portage to go after mud and swamps never happens”. Due to the lack of water in the upstream rivers, it was necessary to raise the water level with the help of sailing and earthen dams or to reload it repeatedly. On many rivers, swimming made it difficult to numerous rapids and rapids. But the main difficulty of navigation on the northern rivers was determined by an extremely short period of navigation, often forcing to spend the winter in places unfit for habitation. The long Siberian winter frightens the inhabitants of European Russia with its frosts and at the present time, meanwhile, in the XVII century, the cold weather was more fierce. The period from the end of the 15th century to the middle of the 19th century is designated by paleogeographers as the “Little Ice Age”. However, the hardest trials fell to those who chose the sea routes. The oceans that washed Siberia had deserted and inhospitable shores, and strong winds, frequent fogs and heavy ice conditions created extremely difficult navigation conditions. Finally, a short but hot summer plagued not only by the heat, but also by the inconceivably bloodthirsty and numerous hordes of gnats - this scourge of taiga and tundra spaces that could bring an unusual person to a frenzy. “Gnus is all flying nasty filth, which in summer, day and night, devours people and animals. This is a whole community of bloodsuckers, working in shifts, around the clock, the whole summer. His possessions are immense, power is boundless. He infuriates horses, driving elks into a marsh. He leads a man into a dark, stupid bitterness. "

The picture of the accession of Siberia will be incomplete, if you do not cover such a factor as armed clashes with the local population. Of course, in most regions of Siberia, resistance to the Russian advancement could not be compared with the battles within the “Kuchumov Yurt”. In Siberia, the Cossacks more often died from hunger and disease than from clashes with Aborigines. However, in armed clashes, Russian explorers had to deal with a strong and experienced adversary in military affairs. The contemporaries were well aware of the warlike inclinations of the Tungus, Yakuts, Yenisei Kirghiz, Buryats and other peoples. Often, not only did they not shy away from battle, but they themselves challenged the Cossacks. At that, many Cossacks were killed and wounded, often for several days "they were sitting under siege from that car." Cossacks, having firearms weapons, had a great advantage on their side and clearly recognized him. They were always very worried if the reserves of gunpowder and lead came to an end, realizing that "without firing of fire in Siberia, you cannot be." At the same time, it was prescribed to them “that they should not be considered for foreigners and that they did not indicate any firing of food”. Without a monopolistic possession of "fiery fighting", the Cossack detachments would not have been able to successfully withstand the military forces of the indigenous Siberian population that were immeasurably superior in number. Squeaking in the hands of the Cossacks were a formidable weapon, but even a skilled shooter could not make them more than 20 shots for a whole day of fierce battle. Hence the inevitability of melee fights, where the advantage of the Cossacks was negated by the multiplicity and good armament of their opponents. With constant wars and raids, the inhabitants of taiga and tundra were armed from head to toe, and artisans produced excellent cold and defensive weapons. Especially highly Russian Cossacks valued weapons and equipment of Yakut artisans. But the Cossacks had the hardest time confronting the nomadic peoples of South Siberia. The life of a nomadic cattleman made the entire male population of nomads professional warriors, and the natural militancy made their numerous, highly maneuverable and well-armed army an extremely dangerous adversary. A one-time performance of the aboriginal population against the Russians would not only lead to a halt in their advance into the depths of Siberia, but also to the loss of already acquired lands. The government understood this and sent instructions to “bring foreigners under the sovereign's hand with caress and greetings, and if possible not to repair the fights and fights with them”. But the slightest miscalculation in the organization of the expedition in such extreme conditions led to tragic consequences. So, during V. Poyarkov's campaign against Amur, more than 40 people from 132 died from hunger and disease over one winter, and as many more died in subsequent clashes. From 105, the people who traveled with S. Dezhnev around Chukotka returned 12. Of the 60 who marched with V. Atlasov to Kamchatka, 15 survived. There were completely lost expeditions. Siberia cost the Cossack people dearly.

And with all this, Siberia was passed by the Cossacks up and down for some half a century. The mind is incomprehensible. To realize their grueling feat of lack of imagination. Whoever imagines at least a little these great and ruinous distances, cannot but suffocate with admiration.

The accession of the Siberian lands cannot be separated from their active development. It became part of the great process of transformation of the Siberian nature of the Russian people. At the initial stage of colonization, Russian settlers settled in a residence in the winter quarters built by Cossack pioneers, towns and ostrogahs. Knocking axes is the first thing that the Russian man proclaimed about his settlement in every corner of Siberia. One of the main occupations of those who settled beyond the Urals was fishing, because, due to the lack of bread, the fish first became the main food. However, at the earliest opportunity, the settlers sought to restore the traditional bread-and-flour basis of nutrition to the Russians. To provide the settlers with bread, the tsarist government massively sent peasants from central Russia to the Cossacks and made them to the Cossacks. Their descendants and Cossacks-pioneers gave in the future the root of the Siberian (1760 year), Trans-Baikal (1851 year), Amursky (1858 year) and Ussurian (1889 year) Cossack troops.

The Cossacks, being the main support of the tsarist government in the province, were at the same time the most exploited social group. Being in the conditions of an acute shortage of people, extremely busy with military affairs and administrative tasks, they were widely used as a labor force. As a military class for the slightest negligence or evil slander, they suffered from the arbitrariness of local commanders and the governor. As a contemporary wrote: “Nobody was flogged as often and as hard as the Cossacks”. The answer was the frequent uprisings of the Cossacks and other servicemen, accompanied by the murders of the hated commanders.

Despite all the difficulties in the time allotted to one human life, the vast and rich region has changed drastically. By the end of the 17th century, about 200 thousand displaced people already lived beyond the Urals - about the same as the Aborigines. Siberia emerged from centuries of isolation and became part of a large centralized state, which led to the cessation of communal-clan anarchy and internal strife. The local population, following the example of the Russians, in a short time significantly improved their life and diet. For the Russian state entrenched extremely rich in natural resources of the earth. It is appropriate to recall the prophetic words of the great Russian scientist and patriot M.V. Lomonosov: "The power of Russia will grow Siberia and the North Ocean ...". And after all, the prophet said this at a time when the initial stage of the development of North Asia was barely over.

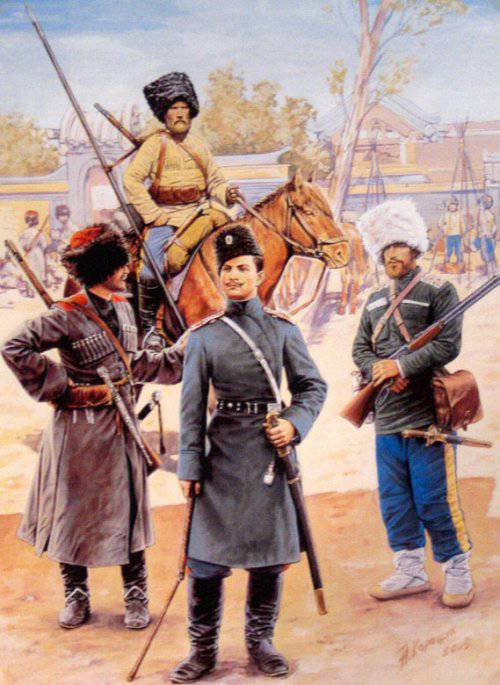

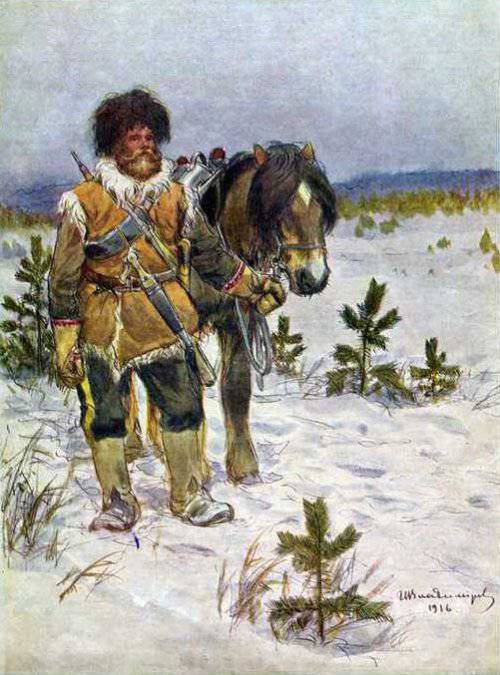

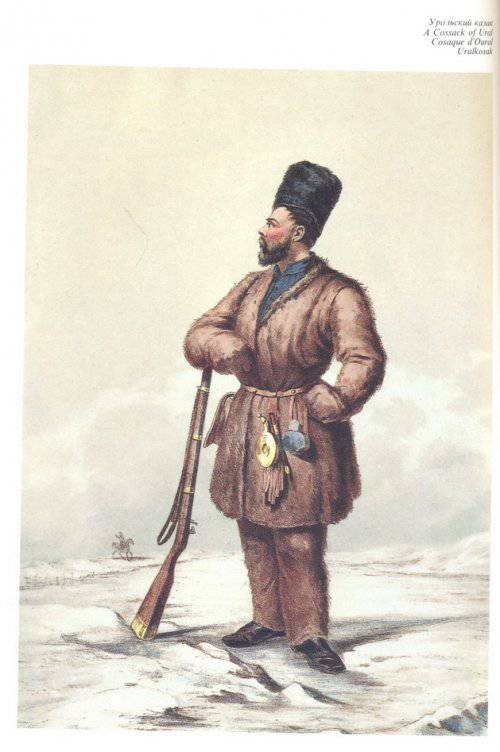

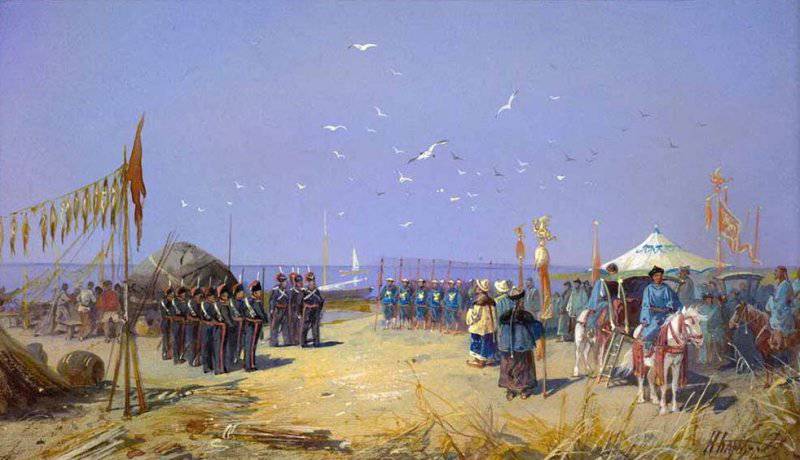

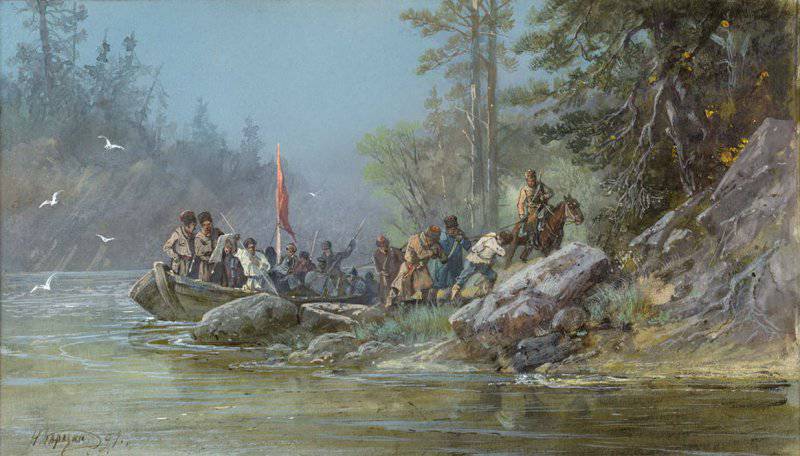

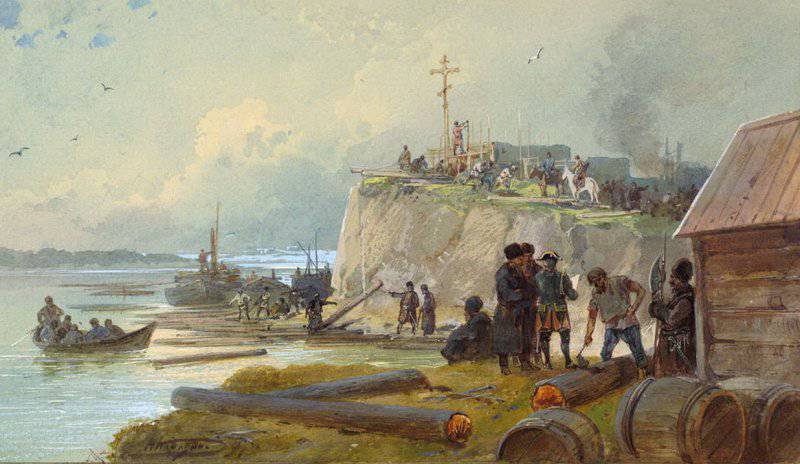

The history of the Siberian Cossacks in watercolors of Nikolai Nikolaevich Karazin (1842 - 1908)

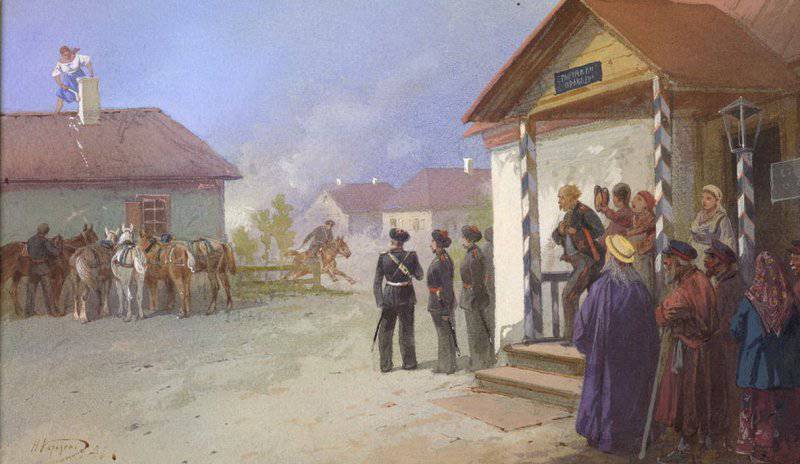

Yamskaya and convoy service in the steppe

Great-great-grandmother of the Siberian Cossacks. The arrival of the party "wife"

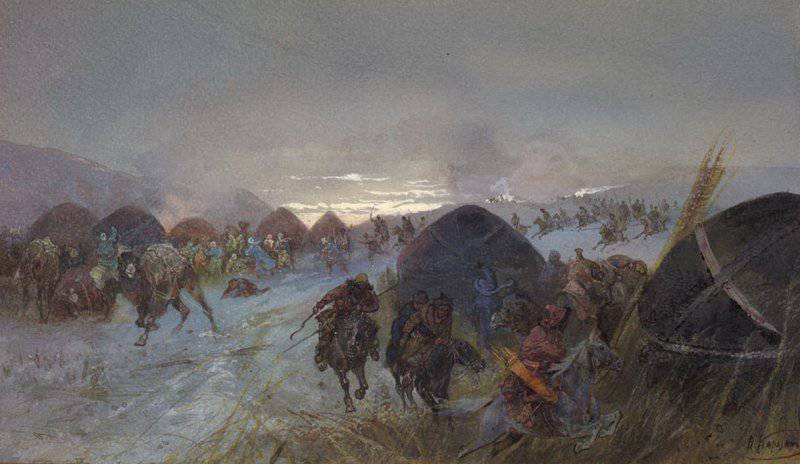

Last Kuchumovsky defeat 1598 of the year. The defeat of the Siberian Khan Kuchum on the Irmeni River, which flows into the Ob, during which almost all members of his family, as well as many notable and ordinary people were captured by the Cossacks

Entrance of the captured family Kuchumova in Moscow. Xnumx

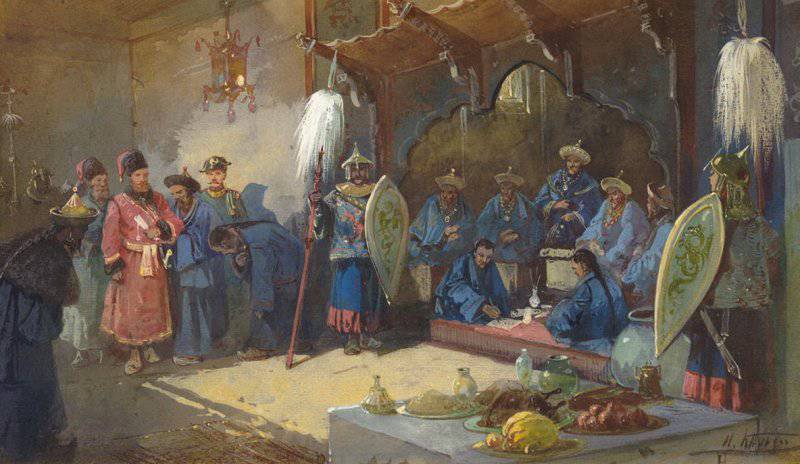

The first half of the XVIII century. Ceremony of the meeting of the Chinese Amban by the caretaker of the military Bukhtarma fishing

The Cossacks in the construction of linear fortresses - fortifications on the Irtysh, built in the first half of the XVII century.

Explaining the middle Kirghiz-Kaisack horde

Intelligence centurion Voloshenin in Semirechki and Ili Valley in 1771 g

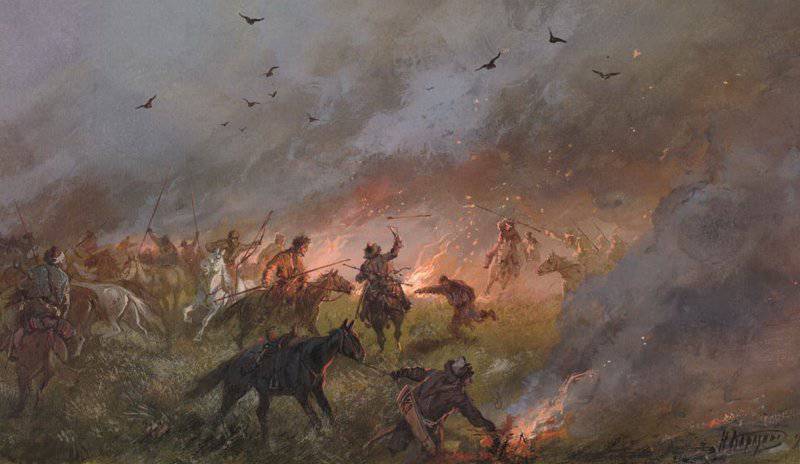

Pugachev in Siberia. The defeat of the crowds of the impostor near Troitsk 21 in May 1774.

Fight with Pugachev

Anxiety in the fortress redoubt

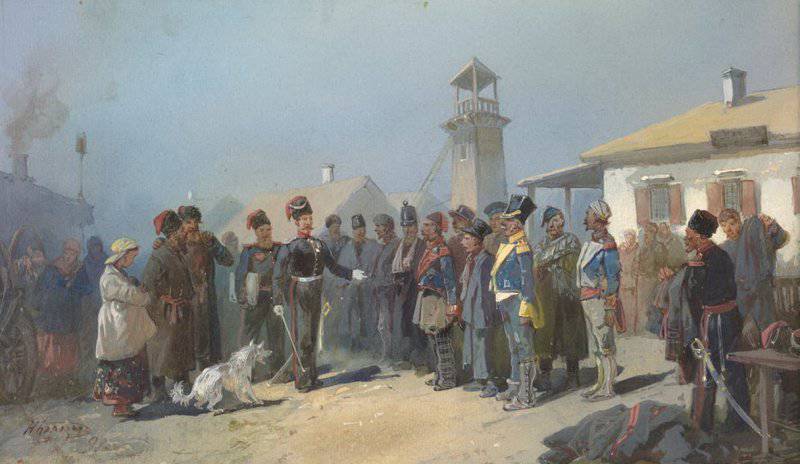

Alien ancestors of the current Siberian Cossacks. Enrollment in the Cossacks of the captured Poles of the army of Napoleon, 1813 g

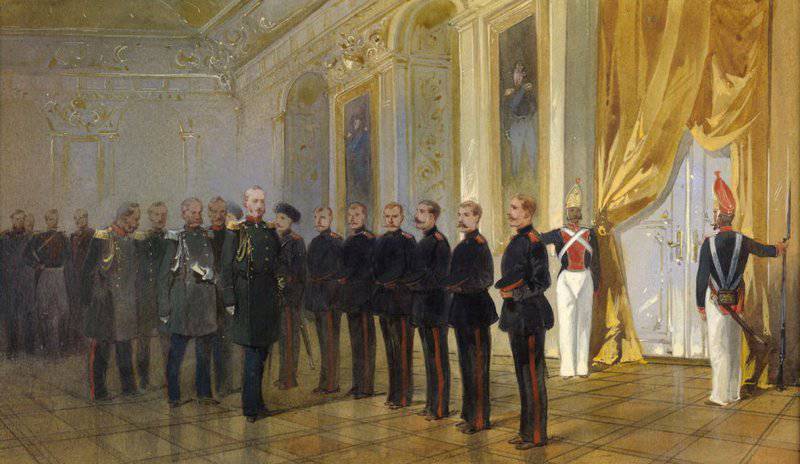

Siberian Cossacks in the Guard.

In the snow

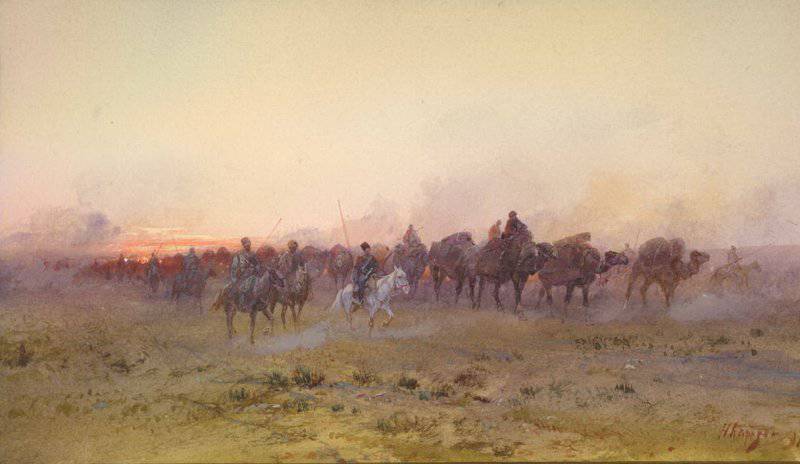

Siberian Cossacks (caravan)

The military settlement service of the Siberian Cossacks

Without a signature

Information