Seniority (education) and the formation of the Don Cossack troops in the Moscow service

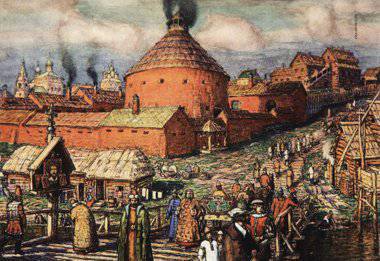

In the article "Old Cossack ancestors»The history of the emergence and development of the Cossacks (including the Don) in the preordyn and Horde periods was described. But at the beginning of the 14 century, the Mongolian empire, created by the great Genghis Khan, began to disintegrate, in its western ulus, the Golden Horde, dynastic unrest (jamming) also periodically arose, in which Cossack detachments subject to individual Mongol khans, murzam and emirs also participated. Under Khan Uzbek, Islam became the state religion in the Horde, and in subsequent dynastic distempers it became aggravated and the religious factor also became actively present. The adoption of one state religion in a multi-confessional state, undoubtedly, hastened its self-destruction and disintegration, for nothing separates people as religious and ideological preferences. As a result of the religious harassment of the authorities, the flight of citizens from the Horde for reasons of faith began to grow. Muslims of other interpretations pulled into the Central Asian uluses and towards the Turks, Christians to Russia and Lithuania. In the end, even the Metropolitan moved from Barn to Krutitsk near Moscow. The heir of Uzbek Khan Janibek during his reign gave the vassals and grandees "great weakness" and when he died in 1357, a long Khan strife began, during which 18 khan changed for 25 years and hundreds of Chingizids were killed. This distemper and the events following it received the name of the Great Zamyatni and was tragic in the history of the Cossack people. The horde quickly rolled to its decline. The chroniclers of that time already considered the Horde not as a whole, but consisting of several Hordes: Sarai or Bolshoi, Astrakhan, Kazan or Bashkir, Crimea or Perekop and Cossack. The troops who died in the distemper of the khans often became ownerless, “free”, not subject to anyone. It was then, in 1360-1400-ies, in the Russian border region, this new type of Cossack appeared, who was not in the service and who lived mainly raids on the nomadic hordes and neighboring peoples or robbed merchant caravans surrounding them. They were called "thieves" Cossacks. Especially many of these “thieves'” patrols were on the Don and on the Volga, which were the most important waterways and main trade routes connecting the Russian lands with the steppe, the Middle East and the Mediterranean. At that time, there was no sharp separation between Cossacks, servicemen and volunteers, often free men were hired for service, and servicemen, on occasion, robbed caravans. It was from that time on the borders of Moscow and other principalities also appeared the mass of "homeless" service Horde people, which the prince's power began to impose on the city Cossacks (the current private security forces, special forces forces and the police), and then in pishchniki (archers). They were exempted from service for service and settled in special settlements, “settlements”. Throughout the entire time of the Horde Zamyatni the number of this military people in the Russian principalities grew steadily. And to draw was from where. The number of the Russian population on the territory of the Horde on the eve of Zamyatny, according to the Cossack historian A.A. Gordeeva, was 1-1,2 million people. By medieval standards, this is quite a lot. In addition to the indigenous Russian population of the steppes of the preordyn period, it has grown greatly due to the “tamga”. In addition to the Cossacks (military estate), this population was engaged in agriculture, crafts, crafts, yamskoy service, served fords and tows, was retinue, courtyard and servants of the khans and their nobles.

In the course of the Great Zamyatni, the Horde warlord, Temnik Mamai, began to acquire more and more influence. He, as before Nogay, began to shift and appoint Khans. The Iranian-Central Asian ulus had also completely collapsed by that time and another impostor appeared on the political scene - Tamerlane. Mamai and Tamerlane played a huge role in the history of the Iranian ulus and the Golden Horde, however, they both contributed to their final death. The Cossacks also actively participated in the discord of Mamaia, including on the side of the Russian princes. It is known that in the 1380 year, the Don Cossacks presented Dmitry the Don Donskoy icon of the Don Mother of God and participated against Mamaia in the Kulikovo battle. And not only Don Cossacks. According to many data, the commander of the ambush regiment of the voivode Bobrok Volynsky was the ataman of the Dnieper Cherkas and transferred to the service of the Moscow Prince Dmitry with his Cossack squad because of strife with Mamai. In this battle, the Cossacks fought bravely from both sides and suffered huge losses. But the worst was ahead. After the defeat on the Kulikovo field, Mamai gathered a new army and began to prepare for a punitive campaign against Russia. But the Khan of the White Horde, Tokhtamysh, intervened in disarray and inflicted a crushing defeat on Mamai. The ambitious Khan Tokhtamysh reunited the entire Golden Horde, including Russia, with his sword and fire, but did not calculate his forces and defiantly and defiantly behaved with his former patron, Central Asian sovereign Tamerlane. Payback was not long in coming. In a series of battles Tamerlane destroyed a huge Golden Horde army, the Cossacks again suffered huge losses. After the defeat of Tokhtamysh, Tamerlane moved to Russia, but disturbing news from the Middle East forced him to change plans. Persians, Arabs, Afghans constantly rebelled there and the Turkish Sultan Bayazet behaved the “European thunderstorm” no less boldly and defiantly than Tokhtamysh. In campaigns against the Persians and Turks, Tamerlane mobilized and took with him tens of thousands of surviving Cossacks from the Don and the Volga. They fought very worthily, as Tamerlane himself left the best reviews. So he wrote down in his notes: “Having mastered the manner of fighting like a Cossack, I equipped my troops so that I could, like a Cossack, penetrate the disposition of my enemies.” After the victorious completion of the campaigns and the capture of Bayazet, the Cossacks requested their homeland, but did not receive permission. Then they arbitrarily migrated to the north, but by order of a wayward and powerful sovereign were overtaken and exterminated.

The Cossack people of the Don and the Volga cost the Great Golden Horde of Smoot (Mouth) 1357-1400 for the Cossacks, the Cossacks survived the hardest times, great national misfortunes. During this period, the territory of the Cossacks consistently underwent devastating invasions of formidable conquerors - Mamaia, Tokhtamysh and Tamerlane. Formerly densely populated and flowering lower reaches of the Cossack rivers turned into deserts. The history of the Cossacks didn’t know such a monstrous story either before or after. But some of the Cossacks survived. When terrible events descended, the Cossacks, led in this troubled time by the most prudent and far-sighted chieftains, moved to neighboring areas, Moscow, Ryazan, Meshchersky principalities and in the territory of Lithuania, the Crimean, Kazan Khanates, Azov and other Genoese cities of the Black Sea coast. The Genoese Barbaro wrote in the 1436 year: "... a people live in the Azov Sea, called Azak-Cossack, who speaks the Slavic-Tatar language." It was from the end of the XIV century that Azov, Genoese, Ryazan, Kazan, Moscow, Meshchersky and other Cossacks became famous in the annals, forced to emigrate from their native places and entered the service of various rulers. These Cossack ancestors, the fugitives from the Horde, were looking for service in the new lands, work, “farm laborers”, at the same time they longed to return home. Already in 1444, in the papers of the Discharge Order, concerning the raid of a detachment of Tatars on Ryazan lands, it was written: “... there was winter and deep snow fell. The Cossacks opposed the Tatars on the arts ... "(skiing).

Since that time, information about the activities of the Cossacks in the composition of the Moscow troops did not stop. Transferred from weapons and the troops to the service of the Moscow prince Tatar grandee brought with them a lot of Cossacks. The horde, breaking up, shared its legacy - the armed forces. Each Khan, leaving from under the authority of the chief Khan, took with him a tribe and troops, including a significant number of Cossacks. According to historical information, the Cossacks were also in the khans of Astrakhan, Sarai, Kazan and Crimea. However, as part of the Volga khanate, the number of Cossacks quickly fell and soon completely disappeared. They went to the service of other masters or became "free." So, for example, there was an exodus of Cossacks from Kazan. In 1445, the young Moscow Prince Vasily II spoke out against the Tatars to protect Nizhny Novgorod. His troops were defeated, and the prince himself was captured. The country began collecting funds for the redemption of the prince and for 200 000 rubles Vasily was released to Moscow. A large number of Tatar nobles came to the prince from Kazan, who joined him in the service with their troops and weapons. As "service people" they were awarded lands and volosts. In Moscow, Tatar speech was heard everywhere. And the Cossacks, being a multinational army, being in the composition of the Horde troops and the Horde nobles, retained their native language, but in the service and among themselves spoke the language of the state, i.e. in Turkic-Tatar. Basil's rival, his cousin Dmitry Shemyaka, accused Vasily of “bringing the Tatars to Moscow, and the cities and volosts they gave to feed, the Tatars and their speech likes more than measures, gold and silver and gives them property ...”. Shemyaka lured Basil on a pilgrimage to the Trinity-Sergius monastery, captivated, overthrew and blinded him, taking the throne of Moscow. But a detachment of Cherkas (Cossacks) loyal to Vasily, led by Tatar princes Kasim and Egun who served in Moscow, defeated Shemyaka and restored the throne to Vasily, since then for the blindness called the Dark One. It was under Vasily II the Dark that the permanent (deliberate) servicemen of Moscow were systematized. The first category consisted of parts of the “town” Cossacks, formed from the “homeless” Horde military people. This unit served as a sentinel and police service for the protection of internal urban order. They were completely subordinate to the local princes and the governor. A part of the city troops was the personal guard of the Moscow prince and submitted to him. Another part of the Cossack troops were the Cossacks of the frontier guard of the marginal lands of the Ryazan and Meshchersky principalities. Payment for the service of the permanent troops was always a difficult matter of the Moscow principality, as indeed any other medieval state, and was carried out by land allotments, as well as receiving salaries and benefits in trade and industries. In the internal life of these troops were completely independent and were under the command of their chieftains. The Cossacks, being in the service, could not actively engage in agriculture, because the labor on earth separated them from military service. They gave surplus land to lease or hired laborers. In the frontier, Cossacks received large land plots and engaged in cattle breeding and gardening. When the next Moscow Prince Ivan III continued to increase the permanent armed forces and improved their weapons.

Under Vasily II and Ivan III, thanks to the Cossacks, Moscow began to possess powerful armed forces and consistently annexed Ryazan, Tver, Yaroslavl, Rostov, then Novgorod and Pskov. The growth of military power of Russia increased with the growth of its armed forces. The number of troops with mercenaries and the militia could reach 150-200 thousands of people. But the quality of the troops, their mobility and readiness increased, mainly due to the increase in the number of “deliberate” or permanent troops. So in 1467, a campaign was undertaken against Kazan. Ataman Cossack Ivan Ruda was elected chief commander, successfully defeated the Tatars and ruined the outskirts of Kazan. Many captives and loot were captured. Decisive actions of the chieftain did not receive the gratitude of the prince, but on the contrary, brought disgrace. Paralysis of fear, humility and servility in front of the Horde very slowly left the soul and body of Russian power. Speaking in campaigns against the Horde, Ivan III never dared to engage in large battles, limited to demonstration actions and the help of the Crimean Khan in his fight with the Great Horde for independence. Despite the protectorate imposed on Crimea by the Sultan of Turkey in 1475, the Crimean Khan Mengli I Giray maintained friendly and allied relations with Tsar Ivan III, they had a common enemy - the Great Horde. So during the punitive campaign of the Golden Horde Khan Akhmat against Moscow in 1480, Mengli I Giray sent the Nogai subordinate to him with the Cossacks to raid the Saray lands. After the useless "standing on the Ugra" against the Moscow troops, Akhmat retreated from Moscow and Lithuanian lands with rich booty to the Seversky Donets. There he was attacked by the Nogai Khan, in the army of which there were Cossacks before 16000. In this war, Khan Akhmat was killed and he became the last recognized Khan of the Golden Horde. The Cossacks of Azov, being independent, also fought wars with the Great Horde on the side of the Crimean Khanate. In 1502, Khan Mengli I Giray inflicted a crushing defeat on the Great Horde Khan, Shane-Akhmat, destroyed the Shed and ended the Golden Horde. After this defeat, it finally ceased to exist. The protectorate of the Crimea before the Ottoman Empire and the liquidation of the Golden Horde constituted a new geopolitical reality in the Black Sea region and made the inevitable regrouping of forces. Occupying lands lying between Moscow and Lithuanian possessions from the north and north-west and surrounded by aggressive nomads from the south and southeast, the Cossacks did not take into account the policies of either Moscow, or Lithuania, or Poland; relations with the Crimea, Turkey, and nomadic hordes built exclusively from the balance of power. And it also happened that the Cossacks received a salary simultaneously from Moscow, Lithuania, the Crimea, Turkey and nomads for their service or neutrality. The Azov and Don Cossacks, occupying an independent position from the Turks and the Crimean khans, continued to attack them as well, which displeased the Sultan and he decided to do away with them. In 1502, the Sultan ordered Mengli I to Giray: "All dashing Cossack Pasha to deliver to Constantinople." Khan intensified repression against the Cossacks in the Crimea, went on a hike and took Azov. The Cossacks were forced to retreat from Azov and Tavria to the north, re-founded and expanded many townships in the lower Don and Donets and moved the center from Azov to Razdory.

After the death of the Great Horde, the Cossacks also began to leave their service on the borders of Ryazan and other bordering Russian principalities, began to go to the “empty steppes of the Batu horde” and occupy their former places in the upper reaches of the Don, along Khopru and Medveditsa. The Cossacks served on the borders under contracts with the princes and were not bound by oath. In addition, entering the service of the Russian princes during the Horde distemper, the Cossacks were unpleasantly surprised by the local order, and having understood the “lawlessness” of the servile dependence of the Russian people on their masters and the authorities sought to save themselves from enslavement and becoming servants. Cossacks inevitably felt like strangers among the common submissive and uncomplaining mass of slaves. The Ryazan princess Agrafena, who ruled with her young son, was powerless to keep the Cossacks and complained to her brother, Moscow Prince Ivan III. For the "ban on the Cossacks leaving the country for tyranny", they took repressive measures, but they gave the opposite result, the outcome increased. So the Don Army was formed again. The departure of the Cossacks of the border principalities laid bare their borders and left them unprotected by the steppe. But the need to organize permanent armed forces put the Moscow princes in the need to make big concessions to the Cossacks and put the Cossack troops in exceptional conditions. As always, one of the most intractable questions in hiring Cossacks in the service was their content. Gradually, there was a compromise in resolving these issues. Cossack units in the Moscow service turned into regiments. Each regiment received a plot of land and a salary and became a collective landowner, like monasteries. More precisely, it was a medieval military kolkhoz, where each fighter had his own share, from whom it was not called “besdolnye”, from whom they were taken, called “disadvantaged”. The service on the shelves was hereditary and lifelong. The Cossacks enjoyed many material and political privileges, retained the right to choose their superiors, with the exception of the oldest appointed by the prince. Keeping internal autonomy, the Cossacks took the oath. Accepting these conditions, many regiments were transformed from the Cossack regiments, into the regiments of the “gunners” and “pishchniki”, and later into the regiments of the Strelets.

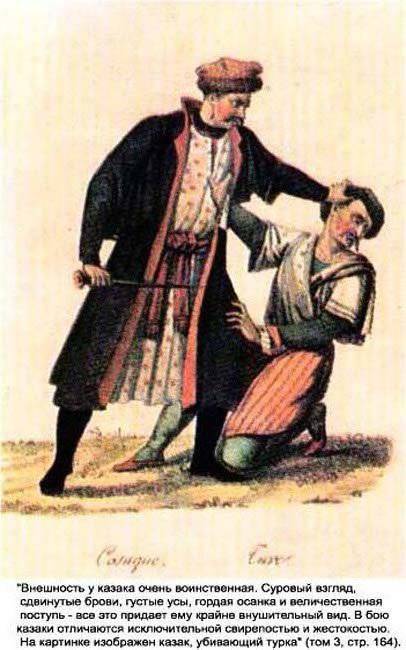

Their chiefs were appointed by the prince and entered the military history under the name "Streletsky Head". Streletsky regiments were the best deliberate troops of the Moscow state of that time and existed for about 200 years. But the existence of Strelets troops was due to a strong monarchy will and weighty state support. And soon, in the Time of Troubles, having lost these preferences, the Strelets troops again turned into Cossacks, from whom they came. This phenomenon is described in the article “COSSACKS IN A QUANTIFIED TIME”. A new typesetting of the Cossacks into archers occurred after the Russian Troubles. Thanks to these measures taken, not all Cossack immigrants returned to the Cossacks. Some remained in Russia and served as the basis for the formation of service classes, police, guard, local Cossacks, gunners and the Streltsy army. By tradition, these classes had some features of the Cossack autonomy and self-government up to the reforms of Peter the Great. A similar process took place in Lithuanian lands. Thus, at the beginning of the 16 century, the 2 of the Don Cossack camp, upper and lower, was re-formed. Riding Cossacks, having settled in their former places within Khopr and Medveditsa, began to clear the Don from the Nogai nomadic hordes. The base Cossacks, ousted from Azov and Tavria, also consolidated on the old lands in the lower Don and Donets, waged war against the Crimea and Turkey. In the first half of the 16 century, the horsemen and the grassroots were not yet united under the rule of one chieftain and each had their own. They were prevented by their different origins and different directions of their military efforts, among the horsemen on the Volga and Astrakhan, from the grassroots on the Azov and Crimea, the grassroots did not abandon the hope of returning their former cultural and administrative center - the Azov. By their actions, the Cossacks protected Moscow from the raids of the nomadic hordes, although they themselves had been outrageous. The communication of the Cossacks with Moscow was not interrupted, in the church sense they submitted to the Sarsko-Podonsky bishop (Krutitsky). The Cossacks needed material assistance from Moscow, Moscow needed military assistance from the Cossacks in the struggle against Kazan, Astrakhan, the Nogai hordes and the Crimea. The Cossacks acted actively and boldly, they knew the psychology of the Asian peoples, who respect only force, and rightly considered the best tactic against them - attack. Moscow acted passively, prudently and cautiously, but they were necessary for each other. So, despite the prohibitive measures of local khans, princes and authorities, at the earliest opportunity, after the end of Zamyatni, Cossack emigrants and fugitives from the Horde returned to the Dnieper, Don and Volga. This continued later, in the XV and XVI centuries. These returnees, Russian historians often give for a fugitive people from Muscovy and Lithuania. The Cossacks who remained on the Don and returned from the neighboring limits unite on ancient Cossack principles and recreate the social and state mechanism that will later be called the Republics of the Free Cossacks, whose existence no one has any doubt about. One of these "republics" was on the Dnieper, the other - on the Don, and its center was on the island at the confluence of the Donets and the Don, the town was called Razdory. In the "Republic" is established the oldest form of government. Its fullness is in the hands of the popular assembly, which is called the Circle. When people from different lands, carriers of different cultures and keepers of different faiths come together, in order to get along, they have to retreat to the level of the simplest, tried and tested for thousands of years, accessible to any understanding. Armed people stand in a circle and, looking at each other’s faces, decide. In a situation where everyone is armed to the teeth, everyone is accustomed to fight to the death and every moment to risk their lives, the armed majority will not tolerate an armed minority. Either expel, or just interrupt. Those who disagree may break away, but later they will not tolerate differences within their group. Therefore, decisions can be made only in one way - unanimously. When the decision was made, the leader, called "chieftain", was chosen for the term of its implementation. They obey unquestioningly. And so until they do what they have decided. In the intervals between the Circles, the elected chieftain also governs - this is the executive power. The ataman, elected unanimously, was smeared with mud and soot, a handful of earth was poured over the gate, like a criminal before drowning, showing that he was not only the leader, but also the servant of society, and in which case he would be punished mercilessly. Ataman elected two assistants, esaulov. Ataman power lasted one year. By the same principle was built management in each town. Gathering in a raid or campaign, they also elected the chieftain and all the chiefs, and until the end of the enterprise, the elected leaders could punish for disobedience by death. The main crimes worthy of this terrible punishment were treason, cowardice, murder (among their own) and theft (again, among their own). The convicts were put in a sack, they poured sand in there and drowned them (“they put them in water”). In the campaign the Cossacks went in different rags. Cold weapons, so as not to shine, soaked in brine. But after hikes and raids they dressed up brightly, preferring Persian and Turkish clothing. As the river settles down again, the first women appear here. Some Cossacks began to take out their families from their former place of residence. But most women were repulsed, stolen or bought. Nearby, in the Crimea was the largest center of the slave trade. Polygamy among the Cossacks was not, the marriage was concluded and terminated freely. For this Cossack was enough to inform the Circle. Thus, at the end of the 15th century, after the final collapse of the united Horde state, the Cossacks who remained and settled on its territory retained their military organization, but at the same time found themselves in complete independence both from the fragments of the former empire and from the Muscovy kingdom that appeared in Russia. The runaway people of other classes only replenished, but were not the root of the rise of troops. Those who arrived were taken to the Cossacks not all and not immediately. To become a Cossack, i.e. to be a member of the army, it was necessary to obtain the consent of the Troop Circle. Not everyone received such consent, it was necessary for this to live among the Cossacks, sometimes for a long time, to enter local life, to “get stuck” and then only permission was given to be called a Cossack. Therefore, among the Cossacks lived a significant part of the population, not belonging to the Cossacks. They were called "besdolnymi people" and "barge haulers." The Cossacks themselves always considered themselves to be a separate people and did not recognize themselves as fleeing men. They said: "we are not serfs, we are Cossacks." These opinions are clearly reflected in fiction (for example, in Sholokhov). Historians of the Cossacks, give detailed excerpts from the chronicles of the XVI-XVIII centuries. describing conflicts between Cossacks and alien peasants, whom the Cossacks refused to recognize as equal to themselves. So the Cossacks managed to survive as a military estate during the collapse of the Great Empire of the Mongols.

By the middle of the 16 century, the geopolitical situation around the Cossacks was very complex. It was greatly complicated by the religious situation. After the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire became a new center of Islamic expansion. The Asian peoples of the Crimea, Astrakhan, Kazan and the Nogai hordes were under the auspices of the Sultan, who was the head of Islam and considered them to be his subjects. In Europe, the Ottoman Empire with varying success opposed the Holy Roman Empire. Lithuania did not leave hopes for the further seizure of the Russian lands, and Poland, in addition to the seizure of land, was intended to spread Catholicism to all Slavic peoples. Being on the borders of the three worlds, Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Islam, Don Cossacks were surrounded by hostile neighbors, but also owed their lives and the existence of skillful maneuvers between these worlds. With the constant threat of attack from all sides required the unification under the authority of one ataman and a common Military Circle. The decisive role among the Cossacks belonged to the lower Cossacks. Under the Horde, grassroots Cossacks carried out service for the protection and defense of the most important trade communications of Azov and Tavria and had more organized control, located in their center - Azov. Being in contact with Turkey and the Crimea, they were constantly in great military tension, and Khoper, Vorona and Medveditsa became the deep rear of the Don Cossacks. There were also deep racial differences, the upper ones were more Russified, the lower ones had more Tatar and other southern bloodlines. This was reflected not only in physical data, but also in character. By the middle of the 16 century, among the Don Cossacks, a number of outstanding atamans appeared, mostly from the lower part, through whose efforts unification was achieved.

And in the Moscow state in 1550, the young Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible began to rule. Having carried out effective reforms and relying on the experience of predecessors, by the year of 1552 he got into his hands the most powerful armed forces in the region and activated the participation of Muscovy in the struggle for the Horde inheritance. The reformed army comprised: 20 thousand royal regiments, 20 thousand archers, 35 thousand boyar cavalry, 10 thousand nobles, 6 thousand urban Cossacks, 15 thousand mercenary Cossacks and 10 thousand mercenary Tatar cavalry. His victory over Kazan and Astrakhan meant victory at the turn of Europe - Asia and the breakthrough of the Russian people in Asia. The open spaces of vast countries opened up before the Russian people in the East, and a rapid movement began with a view to mastering them. Soon, the Cossacks crossed the Volga and the Urals and conquered the vast Siberian Kingdom, and after 60 years the Cossacks sunk to the Sea of Okhotsk. These victories and this great, heroic and incredibly sacrificial advance of the Cossacks to the East, beyond the Urals and the Volga, are described in other articles in the series: Education Volga and Yaik troops; Siberian Cossack Epic; Cossacks and the annexation of Turkestan and others. And the hardest struggle against the Crimea, the Nogai horde and Turkey continued in the Black Sea steppes. The main burden of this struggle also lay on the Cossacks. Crimean Khans lived raiding economy and constantly attacked the neighboring lands, sometimes reaching Moscow. After the establishment of the Turkish protectorate, Crimea became the center of the slave trade. The main prey in raids were boys and girls for the slave markets of Turkey and the Mediterranean. Turkey, being in the share and interest, also took part in this struggle and actively supported the Crimea. But from the Cossacks, they were also in the position of a besieged fortress and under the threat of constant attacks on the peninsula and the sultan's coast. And with the transfer of Hetman Vishnevetsky with the Dnieper Cossacks to the service of the Moscow tsar, all the Cossacks temporarily gathered under the rule of Grozny.

After the conquest of Kazan and Astrakhan, the Moscow authorities were confronted with the question of the direction of further expansion. The geopolitical situation prompted 2 possible directions: the Crimean Khanate and the Livonian Confederation. Each direction had its supporters, opponents, virtues and its own risks. To address this issue, a special meeting was convened in Moscow and the Livonian direction was chosen. In the end, this decision was extremely unfortunate and had fatal, even tragic consequences for Russian history. But in 1558, the war began, its beginning was very successful, and many Baltic cities were occupied. Up to 10000 Cossacks under the leadership of ataman Zabolotsky participated in these battles. At a time when the main forces fought in Livonia, the Don ataman Misha Cherkashenin and the Dnieper hetman Vishnevetsky acted against the Crimea. In addition, Vishnevetsky received an order to raid the Caucasus to help the Allied Kabardians against the Turks and Nogai. In 1559, the attack on Livonia was resumed and after a series of Russian victories, the coast from Narva to Riga was occupied. Under the powerful blows of the Moscow troops, the Livonian Confederation collapsed and was saved by the establishment of a protectorate of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania over it. Livonians requested peace and it was concluded on 10 for years to the end of 1569. But Russian access to the Baltic affected the interests of Poland, Sweden, Denmark, the Hanseatic League and the Livonian Order. The energetic Master of the Order Kettler instituted the kings of Poland and Sweden against Moscow, and they, in turn, after the end of the seven-year war between them, attracted some other European monarchs and a pope, and later even the Turkish sultan. In 1563, the coalition of Poland, Sweden, the Livonian Order and Lithuania ultimately demanded the withdrawal of the Russians from the Baltic states and after its rejection the war resumed. Changes have also occurred in the frontier of Crimea. Getman Vishnevetsky, after marching on Kabarda, went to the mouth of the Dnieper, flew down with the Polish king and re-entered his service. Vishnevetsky's adventure ended tragically for him. He undertook a campaign in Moldova in order to take the place of the Moldavian ruler, but was treacherously captured and sent to Turkey. There he was sentenced to death and dropped from the fortress tower on the iron hooks, where he died in agony, cursing Sultan Suleiman, whose persona is now widely known to our public thanks to the popular Turkish TV series “The Magnificent Century”. The next hetman, Prince Ruzhinsky, again entered into relations with the Moscow tsar and continued to raid the Crimea and Turkey until his death in 1575.

For the continuation of the Livonian War, troops were assembled in Mozhaisk, including 6 thousand Cossacks, and one of the Cossack thousands was commanded by Ermak Timofeevich (the diary of King Stephen Batory). This stage of the war also began successfully, Polotsk was taken and many victories were won. But success ended in grave failure. When attacking Kovel, the chief governor, Prince Kurbsky, made an unforgivable and incomprehensible oversight and his 40 thousandth corps was utterly defeated by an 8 thousandth detachment of Livonians with the loss of the entire convoy and artillery. After this failure, Kurbsky, not waiting for the decision of the king, fled to Poland and switched to the side of the Polish king. Military failures and the betrayal of Kurbsky prompted Tsar Ivan to intensify repressions, and the Moscow forces went on the defensive and with varying success kept occupied areas and the coast. The protracted war drained and bled Lithuania, and it weakened in the fight against Moscow so much that, avoiding a military-political collapse, it was forced to recognize Unia with Poland in 1569, effectively losing a significant part of its sovereignty and losing Ukraine. The new state was called the Commonwealth (Republic of both peoples) and was led by its Polish king and the Sejm. The Polish king Sigismund III, trying to strengthen the new state, tried to draw as many allies as possible into the war against Moscow, even if they were his enemies, namely the Crimean Khan and Turkey. And he succeeded. Through the efforts of the Don and Dnieper Cossacks, the Crimean Khan sat in Crimea as in a besieged fortress. However, taking advantage of the failures of the Moscow king in the war in the West, the Turkish sultan decided to start a war with Moscow for the liberation of Kazan and Astrakhan and to clear the Don and Volga from the Cossacks. In 1569, the sultan sent 18 thousand sipagos to the Crimea and ordered the khan with his troops to go the Don through the Perevolok to expel the Cossacks and occupy Astrakhan. In Crimea, at least 90 thousand troops were gathered and they, under the command of Kasim Pasha and the Crimean Khan, moved upstream of the Don. This trip is described in detail in the memoirs of the Russian diplomat Semyon Maltsev. He was sent by the king as an ambassador to the Nogais, but on the way he was captured by the Tatars and, as a prisoner, followed with the Crimean-Turkish army. With the advance of this army, the Cossacks left their towns without a fight and went towards Astrakhan to connect with the archers of Prince Serebryany, who occupied Astrakhan. Getman Ruzhinsky with 5 thousand Dnieper Cossacks (Cherkasy), bypassing the Crimeans, connected with the Don on Perevolok. In august turkish flotilla reached Perevoloki and Kasim Pasha ordered to dig a canal to the Volga, but soon realized the futility of this venture. His army was surrounded by the Cossacks, deprived of transportation, extraction of food and communication with the peoples to whose aid they went. Pasha ordered to stop digging the canal and drag the fleet into the Volga. Approaching Astrakhan, Pasha ordered the construction of a fortress near the city. But here, his troops were surrounded and blockaded and suffered heavy losses and hardships. Pasha decided to abandon the siege of Astrakhan and, despite the strict order of the Sultan, moved back to Azov. The historian Novikov wrote: “When the Turkish troops approached Astrakhan, the hetman called up from Cherkassy with 5000 Cossacks, together with the Don, won a great victory ...” But the Cossacks blocked all the favorable escape routes and the Pasha led the army back to the anhydrous steppe. Along the way, the Cossacks "plundered" his army. Only 16 thousand troops returned to Azov. Don Cossacks after the defeat of the Crimean-Turkish army returned to the Don, rebuilt their towns and finally and firmly entrenched in their lands. Part of the Dnieper, dissatisfied with the production division, separated from the hetman of Ruzhinsky and remained in the Don. They restored and strengthened the southern town and named it Cherkassk, the future capital of the Army. The successful reflection of the campaign of the Crimean-Turkish army to Don and Astrakhan, while the main forces of Moscow and the Don Army were on the western front, showed a turning point in the struggle for possession of the Black Sea steppes. Since that time, dominance in the Black Sea began to gradually pass to Moscow, and the existence of the Crimean Khanate was extended for 2 centuries not only by the strong support of the Turkish Sultan, but also by the great turmoil that soon arose in Muscovy. Ivan the Terrible did not want a war on 2 fronts and wanted a reconciliation in Black Sea, the sultan after the defeat at Astrakhan also did not want to continue the war. An embassy was sent to the Crimea for peace talks, which was discussed at the very beginning of the article, and the Cossacks were ordered to accompany the embassy to the Crimea. And this, in the general context of Don history, an insignificant event, has become a landmark and is considered the moment of seniority (foundation) of the Don Army. But by that time the Cossacks had already made many brilliant victories and great deeds, including for the benefit of the Russian people and in the interests of the Russian government and state.

Meanwhile, the war between Moscow and Livonia took on an ever-increasing strain. The anti-Russian kaolition managed to convince the European public of the extremely aggressive and dangerous nature of the Russian expansion and to attract the leading European monarchies to their side. Strongly engaged in their Western European squabbles, they could not provide military assistance, but they helped financially. With the money allocated, the kaolition began to hire troops from European and other mercenaries, which greatly increased the combat capability of its troops. The military tension was complicated by internal turmoil in Moscow. The money also allowed the enemy to bribe the Russian nobles abundantly and maintain the 5 column inside the Moscow state. Treason, betrayal, sabotage and opposition actions of the nobility and her servants assumed the character and size of national misfortunes and prompted the royal power to retaliate. After the flight of Prince Kurbsky to Poland and other infidels, brutal persecution of the opponents of autocracy and the rule of Ivan the Terrible began. Then the Oprichnina was established. The specific princes and opponents of the king were ruthlessly destroyed. Metropolitan Philip, who came from a noble family of the Kolychev boyars, opposed the massacres, but he was deposed and killed. In the course of the repressions, most of the noble boyars and princely families died. For the history of the Cossacks, these events also had great, albeit indirect significance. From this time until the end of the XVI century. In addition to the indigenous Cossacks, military servants of the boyars executed by Ivan the Terrible poured into the Don and the Volga from Russia, nobles, battle serfs and boyar children who did not like the tsarist service and the peasants whom the state began to attach to the ground. “We don’t think in Russia,” they said. “Reign tsar in Moscow, and we, the Cossacks, on the Quiet Don.” This stream repeatedly increased the Cossack population of the Volga and the Don.

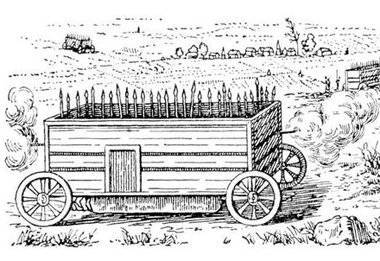

The difficult internal situation was accompanied by severe failures at the front and created favorable conditions for the activation of the raids of the nomadic hordes. Despite the defeat of Astrakhan, the Crimean Khan also craved revenge. In 1571, the Crimean Khan Devlet I Giray successfully chose the moment and successfully broke through with a large detachment to Moscow, burned its surroundings and took tens of thousands of people into captivity. The Tatars had long developed a successful tactic of a secretive and lightning breakthrough into the Moscow limits. Avoiding the river crossings, which greatly reduced the speed of movement of the light Tatar cavalry, they passed along the river watersheds, the so-called "Ants of the Shlyakh", which went from Perekop to Tula along the upper reaches of the tributaries of the Dnieper and the Seversky Donets. These tragic events demanded an improvement in the organization of the protection and defense of the border strip. In 1571, the king entrusted the governor M.I. Vorotynsky develop the order of service of the border Cossack troops. High-level “border guards” were summoned to Moscow and the Charter of the Border Service was drafted and adopted, detailing the procedure for carrying not only the border guard service, but also the guard, intelligence and patrol service in the border area. The duty of service was assigned to parts of the service urban Cossacks, part of the service children of the boyars and the settlements of the Cossacks. Watchmen of service troops from the Ryazan and Moscow region lands descended to the south and southeast and merged with the patrols and pickets of the Don and Volga Cossacks, thus observation was conducted to the limits of the Crimea and the Nogai Horde. Everything was written down to the smallest detail. The results were not slow. The following year, the breakthrough of the Crimeans in the Moscow region ended for them a great catastrophe at the Young. The Cossacks took the most direct part in this great defeat, and the ancient and ingenious Cossack invention “walk-city” played a decisive role. On the shoulders of the defeated Crimean army, Don Ataman Cherkashenin, with Cossacks, broke into the Crimea, captured many loot and prisoners. The unification of the upper and lower Cossacks also belongs to this time. The first joint chieftain was Mikhail Cherkashenin.

It was in such a complex, controversial and ambiguous domestic and international situation that the Don Army was restored in the new post-war history and its gradual transition to the Moscow service. And the decree accidentally found in the Russian archives cannot cross out the previous turbulent history of the Don Cossacks, the birth of their military caste and people's democracy in the conditions of the nomadic life of the neighboring peoples and their continuous communication with the Russian people, but not under the authority of the Russian princes. Throughout the history of the Independent Army of the Don, relations with Moscow have changed, sometimes taking on the character of hostility and sharp discontent on both sides. But discontent most often arose on the part of Moscow and ended with a contract or a compromise and never led to treason on the part of the Don Army. A very different situation was demonstrated by the Dnieper Cossacks. They arbitrarily changed their relations with the supreme power of Lithuania, Poland, Bakhchisarai, Istanbul and Moscow. From the Polish king they transferred to the service of the Moscow tsar, betrayed him and returned back to the service of the king. Often served in the interests of Istanbul and Bakhchisarai. Over time, this impermanence only grew and took on more and more perfidious forms. As a result, the fate of these Cossack troops was completely different. The Don Army, in the end, firmly fell on the Russian service, and the Dnieper Cossacks, in the end, was eliminated. But that's another story.

http://topwar.ru/22250-davnie-kazachi-predki.html

http://topwar.ru/24854-obrazovanie-volzhskogo-i-yaickogo-kazachih-voysk.html

http://topwar.ru/21371-sibirskaya-kazachya-epopeya.html

http://topwar.ru/26133-kazaki-v-smutnoe-vremya.html

http://topwar.ru/22004-kazaki-i-prisoedinenie-turkestana.html

Gordeev A.A. History of the Cossacks

Shamba Balinov What was the Cossacks?

Information