"It's not for nothing that the whole of Russia remembers." Battle of Shevardino

Attack of the Shevardinsky redoubt. Lithography after N. Samokish's drawing

The Battle of Shevardino became the prelude to the Battle of Borodino. It is marked by the same tenacity, the same moral and spiritual confrontation of opponents, which, but on a larger scale, will appear in the Battle of Borodino. And the historiography of this battle presents us with the same discrepancy in its interpretation by both sides as the historiography of the Battle of Borodino.

F. Glinka writes:

However, nothing foreshadowed the bitterness that soon manifested itself in the battle on the left flank of our position, and the bitterness was all the more unexpected because it would seem that it should not have happened, because according to Kutuzov’s intention expressed the day before, this flank, in the event of an enemy attack , it was necessary to retreat to the Semenovsky flushes. Instead, the Russians fought here as if it were the day of their last battle.

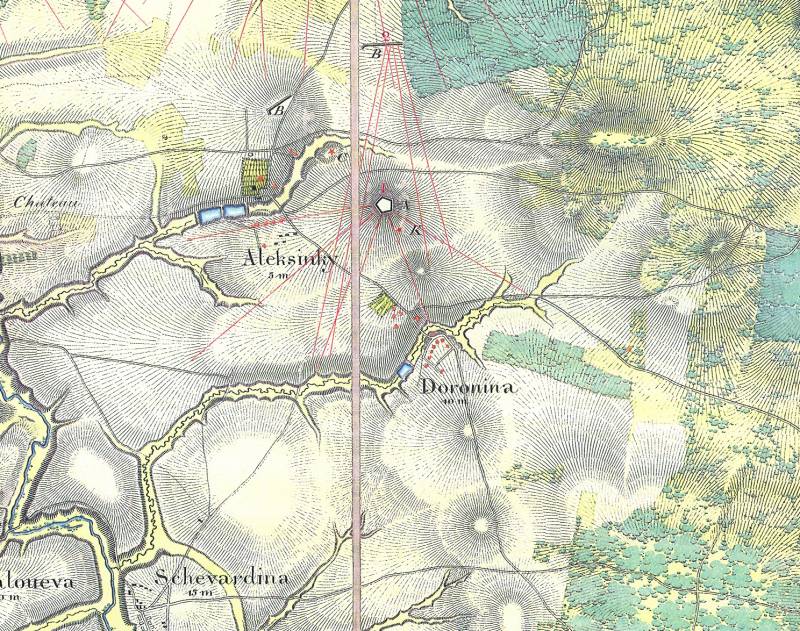

Red numbers 1 and 2 indicate Russian fortifications (Shevardinsky redoubt and the battery supporting it from the east); red lines indicate the number of guns. The names of the villages of Aleksinki and Shevardino are swapped. This plan was taken by the French topographical engineers Press, Chevrier and Regno “a few weeks later” after the Battle of Borodino and captured by our Cossacks as a trophy in November 1812 near Korytnya. The original is stored in the Lefortovo Military Historical Archive (F. 846. Op. 16. D. 3803. L.1). It is especially good because it gives a complete nomenclature of Russian fortifications on the Borodino field. In particular, it is on it that we find the mentioned Russian fortification under the number 2, located east of the Shevardinsky redoubt to support it, as well as a redoubt to the west of Borodino with 4 guns, which completely dropped out of the historiography of the Battle of Borodino. Unfortunately, I didn’t save the entire plan - the disk with the illustrations was out of order. However, there is a small black and white copy which I have also enclosed for reference; the mentioned Borodino redoubt is marked there with the number 8. On the attached colored fragment of the French plan, red stars with the letters “C” and “K” indicate Napoleon’s headquarters, respectively, at the beginning of the Borodino (not Shevardino!) battle and at its end. Both of our fortifications, the Shevardinsky redoubt and the battery supporting it numbered 2, after the Russian army abandoned the position at Shevardin, were turned into French fortifications (marked with the letters “A” and “B”, respectively). Another battery under the letter "B" was erected by the French to protect Napoleon's headquarters

“Surprise” turns out to be the key word in describing the Battle of Shevardin, but with one caveat: if Napoleon’s attack on the 24th was unexpected for us, we did not expect it on that day! - then for the French, such a surprise was the stubborn resistance of the Russian troops, which they arrogantly called “stupid” and “disastrous.”

D. V. Dushenkevich, lieutenant of the Simbirsk Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division, says:

“Distant shots” - this was the work of our rearguard at Valuevo, two miles ahead of Borodino, where “our cavalry and Cossacks destroyed several squadrons of its best cavalry, and captured Adjutant Ney.” The fact that this matter, as Konovnitsyn writes, took place “in the morning... shortly before the rearguard entered the army position,” and the battle along the Great Smolensk Road, in front of the center of our position, lasted “several hours,” suggests that this matter was mixed with case at the Borodino redoubt, which took over the retreat of our rearguard. This is confirmed by the testimony of the “old Finnish”, who says:

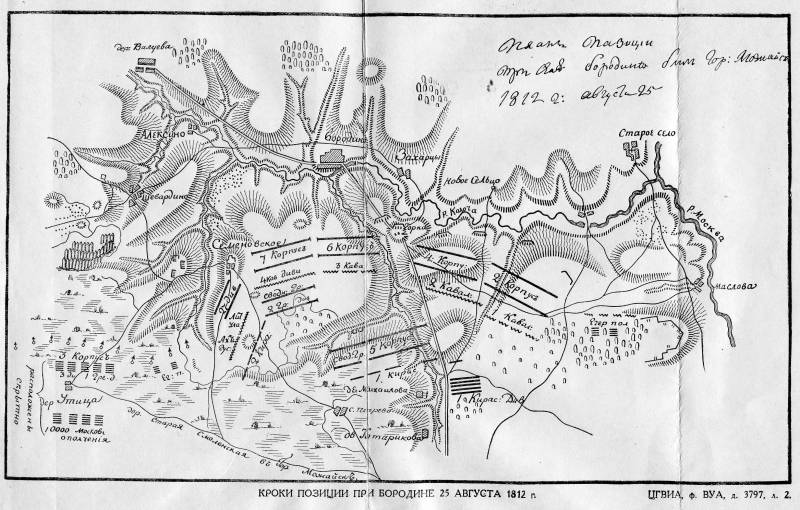

Crocs of the Borodino position, attached to Kutuzov’s report to Emperor Alexander on August 25 - it clearly shows that there is no fortification on the central mound yet

The Borodino redoubt was abandoned sometime after noon - this time is indicated by Barclay in his report:

When approaching the position of our army, the French army stopped at a distance of a cannon shot, which forced our entire army to become armed right up to the very reserves, as reported by F. Ya. Mirkovich:

The Horse Guards, in which Mirkovich served, belonged to the 1st Army and stood deep in reserve, near the village of Knyazkovo; this gives us an idea of the combat readiness of our entire army on that day.

This movement was already a consequence of the orders of Napoleon, who arrived at the line of his troops at two o'clock in the afternoon.

In the 18th bulletin of Napoleon, the attack made by the French army on the left flank of our position is as follows:

The emperor, having learned about this, decided not to hesitate and take this position by storm. He ordered the King of Naples to cross the Colocha with Compan's division and cavalry.

Prince Poniatowski, who approached from the right, was able to go around the position.

At four o'clock the attack began. An hour later, the enemy redoubt was captured along with the cannons, the main enemy forces were expelled from the forest and put to flight after a third of their composition remained on the battlefield. At seven o'clock in the evening the fire ceased.

What do we actually see based solely on the evidence of sources?

Poniatowski's corps was the first to get involved. Kolaczkowski (headquarters of Poniatowski’s 5th Corps) says:

The Cossacks standing on the Old Smolensk Road reported the approach of the enemy. "Soon he appeared in large columns of cavalry, infantry and artillery and clearly showed his intention to attack the left flank of the army," – writes in his report the commander of the 4th Cavalry Corps, Mr. K.K. Sievers.

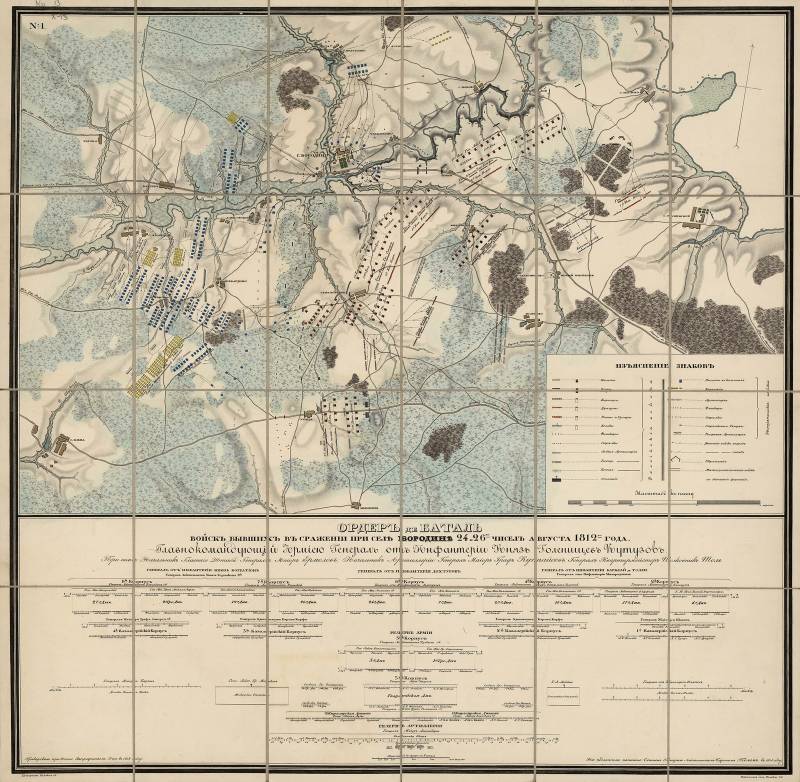

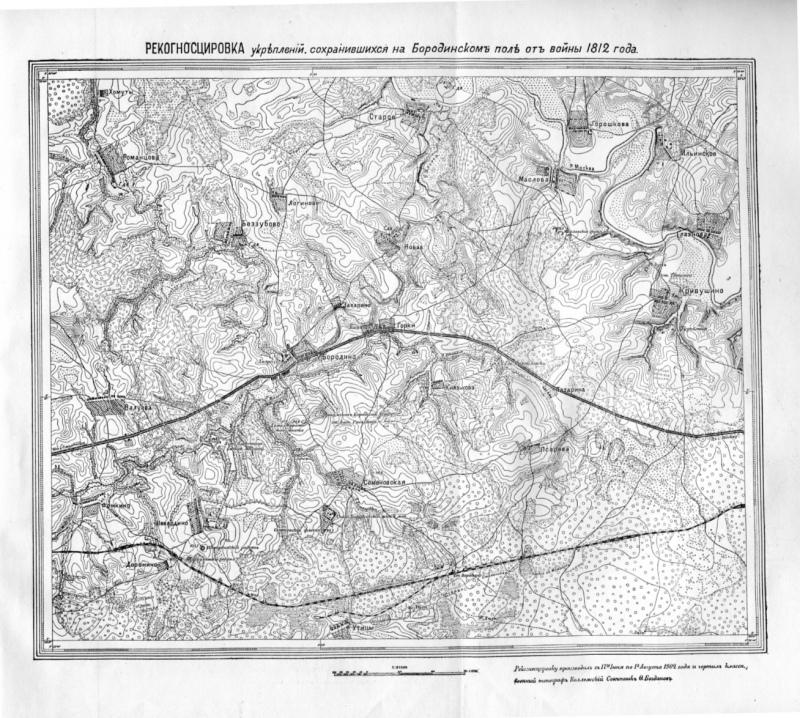

Plan K.F. Tolya, where those huge French batteries in the area of Shevardino and Aleksinka are visible, about which the plan of Press, Chevrier and Regnault is silent; and 3) a plan for reconnaissance of fortifications surviving from the War of 1812, which was drawn up by military topographer F. Bogdanov in August 1902 in preparation for the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino; it is here that we find the Krivushinsky fortifications, which guarded Napoleon’s headquarters after the Battle of Borodino from August 27 to 28 and which, therefore, are documentary evidence that Napoleon did not at all consider himself the winner in the Battle of Borodino

N. I. Andreev (50th Chasseur Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division) tells, confirming the time of the start of hostilities on our left flank: “It was August 24 at 2 pm. Before the people had even eaten, the battalion was ordered to go to the riflemen, and the 3rd Grenadier Company moved forward from the regiment, but stood near the edge of the forest, where I was. Our riflemen were in the forest for three hours.”

The Poles themselves were so little sure that they were attacking the left flank of the Russian position that they considered this attack a collision with the Russian rearguard. “The copses and bushes covered the Russian rearguard and did not allow us to accurately determine its location,” says Kolachkovsky. “Only two hillocks were visible, of which the nearest one contained a fortification armed with strong artillery, and the rear one, lower and 500 fathoms distant from the first one, was adjacent to the forest and seemed to serve as shelter for the reserve.”

Here we have the first (and, it seems, the only) undoubted evidence of two fortifications that were built on the left flank of the Russian position - the Shevardinsky redoubt and the battery covering it from the east. On the French map they are marked 1 and 2 respectively.

“The position taken by the Russians a few hundred fathoms in front of their main position had the character of an advanced one, designed to break the first attacks of the enemy,” continues Kolachkovsky. - Soon, fire flashed from the fortification, a hail of cannonballs showered the head of the Polish column and forced the battalions to turn around. Prince Poniatowski built a battle order in relation to the conditions of the area.

The battalions of the 16th Division moved with riflemen in front; the battalions of the 18th Division, formed in the same order, formed the right flank and began a battle with the enemy rangers, who stubbornly held out in dense thickets; 24 guns were moved to the hill opposite the redoubt to bombard the plain ahead.

The cavalry provided the right flank and maintained communication between the left flank of the 5th Corps and the rest of the Grand Army.

On both sides, the most lively battle ensued, with a noticeable preponderance of Russian artillery, which, occupying a more advantageous position, showered the Polish lines with a hail of shells. After a half-hour battle, the position of the Polish battery was strewn with people and horses.

Evidence of the same battle from the Russian side in Sivers’ report:

Enemy tyraliers and our riflemen, as well as batteries from both sides, began to operate.

Two squadrons of the Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment, located at the cover of the left battery under the command of Captain Aleksandrovich, struck one infantry column approaching the battery and overturned it; Captain Bibikov with the flankers stopped the enemy flankers intending to go around the flank.”

The "left battery" here referred to was Lieutenant-Colonel Parkenson's Horse Artillery Battery No. 9, consisting of eight guns. It was installed on the Doroninsky mound southwest of the Shevardinsky redoubt and, according to the documents, “the first, having opened the battle, held back the enemy that was advancing strongly, bringing it under the main battery,” that is, the Shevardinsky redoubt.

The other four guns of this battery were installed “on the right side of the large redoubt,” apparently in that same “rear” fortification 500 fathoms east of the Shevardinsky redoubt that Kolachkovsky speaks of. Both of these batteries were covered by Sievers' cavalry. French authors write that in the battle in this area the Poles lost up to 150 people as prisoners. And only now French troops appear on the battlefield.

From Sievers' report:

i.e., on the village of Doronino and the forest to the south of it.

Andreev (50th Jaeger Regiment) reports the same: "Then the enemy, to the right of us, began to appear in columns on the field." It was Davout's infantry and Murat's cavalry that led the attack on our left flank. Taking into account the time that, according to Andreev, our rangers “were in the forest” from the moment they moved there - “three hours”, it turns out that the French troops really appeared in front of our left flank no earlier than the 5th hour in the afternoon.

We find confirmation of this in French sources. Vossen (111th line regiment of the Kompan division) says: “About 4 o’clock in the evening, General Davout’s corps lined up along the road along the Kolochi River; The 2nd brigade of Compan's division, 111th and 108th regiments, received orders to cross the Kolocha; on its right bank there was a hill, although unfortified, but well furnished with Russian guns. Enemy infantry and cavalry were also visible close to him. Our brigade moved forward in closed ranks. The enemy opened cannon fire, we formed a front, rifle fire began, and soon a murderous battle began.”

So the French units, advancing from the Great Smolensk Road, entered into action at Shevardin later than the Poles; the latter had already suffered significant losses before, as Kolachkovsky writes, "large masses of French reserve cavalry began to form regimental ledges between the left flank of the 5th Corps and Compan's division of the 1st Corps, which moved forward to attack the redoubt."

A colorful description of this attack is given by the French Colonel Griois: “Our troops presented a wonderful sight in their animation. The clear sky and the rays of the setting sun, reflected on sabers and guns, increased its beauty. The rest of the army watched from their positions the advancing troops, proud that they had the honor of opening the battle; she accompanied them with shouts of approval. Discussions about methods of attack and possible obstacles were peppered with military jokes. And everyone rightly believed that the enemy would retreat before such troops; The emperor must have been convinced of this if he tried to attack at such a late hour against a strong position, which the enemy apparently valued, since taking it would open up his left flank.”

Kompan crossed Kolocha “much higher than Shevardin, over the hill from the redoubt” and, as a Russian source notes, “unexpectedly for us.” Following Kompan, “moving back along the Great Road somewhat back,” Murat’s cavalry (1st and 2nd cavalry corps) crossed Kolocha. Two other divisions of Davout's corps, Friant and Moran, crossed Kolocha near the village of Aleksinki, apparently in the area of the Aleksinsky Ford.

It is reported that, having passed Fomkino, Kompan divided his troops: he himself, at the head of the 1st brigade (57th and 61st regiments), moved to Doronino, intending to capture the Shevardinsky redoubt from the south, the other brigade (111th and 108th regiments) ) moved in the direction between the redoubt and the village of Shevardino, bypassing the redoubt from the north. Murat supported Compan's attack.

The description of this attack by the French authors follows the lapidary nature of the 18th bulletin. Pele: "The enemy was overthrown, and the redoubt was taken in less than an hour with the most brilliant valor". Caulaincourt: "This attack was carried out with such force that we took possession of the redoubt in less than an hour." Labom: “... having risen high enough, the Kompan division surrounded the redoubt and took it after an hour-long battle. Trying to return, the enemy was utterly defeated; finally, after 10 p.m., he left the neighboring forest and fled in disorder to a high hill to join the center of his army.

It seems that nothing compares to the arrogance of French authors.

But here is what the Russian sources report. N.I. Andreev (50th Jaeger Regiment) tells:

The massacre did not last long, and their regimental commander was wounded in the back of his body by a bullet. They carried him away, and the regiment began to waver.

His place (that is, the regiment commander - author's note) was taken over, the regiment was stopped, and he again rushed with bayonets and worked gloriously.

Then they stopped, driving the enemy away, and they replaced us.

However, our rangers, who occupied Doronino and the forest south of this village, “bypassed by other enemy columns,” were forced to retreat to the redoubt. Their retreat and removal of guns from the Doroninsky mound was covered by Sivers' cavalry, which attacked the enemy infantry and cavalry.

At the same time, a battle breaks out in another part of the position.

The commander of the 26th Infantry Division, Mr. I. F. Paskevich:

They held out until the evening, the enemy could not overthrow my Jaeger brigade, and although of the 12 guns of Colonel Zhuravsky (actually Zhurakovsky; light No. 47th company - author's note), many were knocked out and at least half of the horses were lost , but the artillery did not retreat.

This matter cost me up to 800 people, and a horse under me was wounded by a bullet.”

The 26th Infantry Division of Paskevich stood on the right flank of the 2nd Army, adjoining the center of the Borodino position, which means that on August 24 the battle went along the entire front of the 2nd Army, i.e. not only between the village of Shevardino and the forest south of the Shevardinsky redoubt, but also to the right of the village of Shevardino, against the center of the Borodino position. The Chief of Staff of the 2nd Army, Mr. M., also writes about this. E.F. Saint-Prix:

This is probably the main thing for us news days on August 24, allowing you to imagine the real scale of the Shevardino battle.

That this was exactly the case is confirmed by the testimony of the chief of artillery of the 2nd Army, Mr. K.F. Levenshtern, who reports on the actions of the batteries he placed “on the right flank of the 2nd Western Army”: “light company No. 47 and 4 guns of light company No. 21, which, despite the strongest cannonade from the enemy batteries, responded with the greatest damage to the enemy until the very night.”

Here, "in the center of the line", where the "enemy crashed", the most fierce battle took place. Prince Eugen of Württemberg says: “The site of the main, most stubborn battle, apparently, became the bushes in front (that is, to the north. - Author's note) of Shevardin. The rifle fire thundered there with such force, as if thirty battalions were directly involved in this matter.”

The picture of the battle in this area is supplemented by the story of N. B. Golitsyn, Bagration's orderly:

The fighting battalions, Russian and French, with a stretched front, separated only by a steep but narrow ravine, which did not allow them to act cold weapons, approached at the closest distance, opened one on the other rapid fire, and continued this murderous skirmish until death scattered the ranks on both sides.

The sight became even more striking in the evening, when rifle shots sparkled in the darkness like lightning, at first very thickly, then less and less, until everything died down due to the lack of fighters.”

This unprecedented bitterness of the opponents cannot be explained solely by tactical considerations; its reason was rather moral and rooted in the spirit of the troops: the French, led by Napoleon, considered themselves invincible and did not even think that they could yield to anyone on the battlefield; The Russians, embittered by the long retreat and impunity of the enemy, who had taken advantage of their forced inaction for so long, were looking here for an opportunity to finally satisfy their thirst for revenge and settle accounts with the hated enemy. No one thought about mercy and did not seek it for themselves.

Hence the huge human losses in the ranks of those who fought. And we emphasize that these losses were primarily the result of the self-sacrifice of the troops. The fact that French historiography does not provide evidence of this fierce battle only proves that in reality the French have nothing to boast about before the Russians at Borodino.

However, on their side we find evidence that does not quite fit into the dogma of Bulletin 18. So, Kolachkovsky, mentioning the entry into the business of the Kompan division and "large masses of the French reserve cavalry", continues: “A hot battle ensued. The redoubt changed hands several times and finally at 9 o’clock in the evening it remained with the French.”

Segur paints a similar picture: “Compan deftly took advantage of the mountainous terrain; the hills served him as platforms for placing guns with which he fired at the redoubt, and as a cover for the infantry, which was built in columns. The 61st Regiment took the redoubt three times and was driven out three times, but at last he took possession of it, bleeding and losing half of the soldiers.

Tyrion, the senior sergeant of the 2nd cuirassier regiment of Nansouty’s corps, also speaks about the duration of the Shevardino battle: “Until the evening the light cavalry did not cease making their numerous attacks on the flank and on both sides of the redoubt, until the Russians cleared it and it remained in our hands.”

Coignet (the headquarters of the imperial guard) also writes about the “terrible efforts” required to capture the Shevardinsky redoubt.

That the Shevardinsky redoubt really changed hands during the battle is also confirmed by Prince Eugene of Württemberg, who was next to Kutuzov during this battle: “One report was replaced by another: either they announced that the enemy had taken possession of the redoubt, then they reported that he had been beaten off again.”

In Russian sources we also find vivid details of the battle for the redoubt.

Dushenkevich, lieutenant of the Simbirsk infantry regiment of the 27th division, says:

The excessive superiority of the enemy forces forced the grenadier regiments behind us to move to meet them, and by the time they approached us, we were already bombarded with our redoubt by grenades, cannonballs, grapeshot and bullets.”

However, the grenadier regiments did not enter the battle as quickly as it might seem from Dushenkevich’s story.

We learn about this from the story of the St. George Cavalier from the Neverovsky division:

“They’re in a fever” means: they’re trying to recapture the redoubt from a numerically superior enemy with small forces. We find confirmation of this in the report of Sievers, who writes that he tried twice, but in vain, to recapture the redoubt.

Продолжение следует ...

Information