An-12 in Afghanistan

In a rich variety of events stories An-12 Afghan war was destined to occupy a special place. Afghanistan has become an extensive chapter in the biography of a transporter, full of combat episodes, hard work and inevitable losses. Almost every participant in the Afghan war had to deal with military transport in one way or another. aviation and the results of the work of transporters. As a result, the An-12 and the Afghan campaign turned out to be difficult to imagine without each other: the participation of the aircraft in the events there began even before the Soviet troops entered and, lasting more than a decade, continued after the departure of the Soviet Army.

In the broadest way, BTA aircraft began to be involved in work on Afghanistan after the April Revolution in the country, which took place on April 11 of the year 1978 (or 7 of the month of the Saur 1357 of the year according to the local lunar calendar - in the country, according to the present calendar, the yard was 14 th century). The Afghan revolution had its own special character: in the absence of revolutionary strata in a semi-feudal country (by Marxist definition, only the proletariat free from private property can belong to those) the army had to accomplish it, and the former commander-in-chief of the Air Force, Abdul Kadir, who was removed from office by the former authority of Crown Prince Mohammed Daoud. The officer with considerable personal courage and stubbornness, being out of work, headed the secret society of the United Front of the Communists of Afghanistan, but being a man to the core of the military, after “overthrowing despotism” transferred full power to the more democratic political people in political affairs Party of Afghanistan '(PDPA), and he himself chose to return to the usual business, taking literally won the post of Minister of Defense in the new government. The commander of the Air Force and Air Defense became Colonel Gulyam Sahi, who was the head of the Bagram airbase and contributed a lot to the overthrow of the previous regime, organizing the strikes of his pilots on the "stronghold of tyranny" in the capital.

The PDPA leaders, who came to power in the country and were fascinated by the ideas of the reorganization of society, embarked on radical transformations with the aim of building socialism as soon as possible, which it was planned to achieve in five years. In fact, it turned out that it was easier to carry out a military coup, than to govern a country with a pile of economic, national and social problems. Faced with a confrontation committed to the traditions, way of life and religious principles of the population, the plans of revolutionaries began to acquire violent forms.

It has long been known that the road to hell was laid out with good intentions: the implanted reforms ran into opposition to the people, and the directive abolition of many commandments and foundations became for the Afghans personal intervention, from time immemorial here intolerable. The alienation of the people from power was suppressed by new violent measures: a few months after the Saur revolution, public executions of “reactionaries” and clergy began, repression and cleansing became widespread, capturing many of yesterday’s supporters. When the authorities in September 1978 began to publish lists of executed in the newspapers, 12 already had thousands of names in the first, more and more prominent in the society of people from party members, merchants, intellectuals and military. Already in August 1978, among other detainees, was also Minister of Defense Abdul Kadir, who was immediately sentenced to death (he was saved from this fate only after repeated appeals by the Soviet government, worried about the excessively clearing revolutionary process).

Local discontent quickly escalated into armed uprisings; It could hardly have happened otherwise in a country not spoiled by benefits, where honor was considered to be the main advantage, devotion to traditions was in the blood and as traditionally a fair portion of the population had weapon, valued above prosperity. Armed clashes and insurrections in the provinces began as early as June 1978, and by the winter they acquired a systemic character, covering also the central regions. However, the government, just as usual relying on force, tried to suppress them with the help of the army, making extensive use of aircraft and artillery for strikes against recalcitrant villages. Some deviation from the democratic goals of the revolution was considered all the more insignificant because the resistance of the disgruntled was of a focal nature, was fragmented and, for the time being, few in number, while the insurgents themselves were seen as derogatory and backward with their grandfather's guns and sabers.

The true scale of resistance and the intensity of events was already apparent several months later. In March, 1979, in Herat, the third largest city in the country and the center of a large province of the same name, broke out in an anti-government insurgency, to which the local military garrison joined with its commanders in the most active way. Only a few hundred people from the 17 Infantry Division remained on the side of the authorities, including the Soviet military adviser 24. They managed to retreat to the Herata airfield and gain a foothold while holding it in their hands. Since all the warehouses and supplies were in the hands of the rebels, the rest of the garrison had to be supplied by air, delivering foodstuffs, ammunition and reinforcements from transport airplanes from the airfields of Kabul and Shindand.

At the same time, the danger of the development of the insurrection and the coverage of the new provinces by it was not ruled out; even the rebel infantry division, numbering 5000 bayonets, was expected to attack Kabul. The local rulers, stunned by what was happening, literally bombarded the Soviet government with requests for urgent assistance with both weapons and troops. Not really trusting their own army, which turned out to be not so reliable and committed to the revolution, in Kabul they saw a way out only in the urgent involvement of parts of the Soviet Army, which would assist in suppressing the Herat insurgency and protect the capital. To help come quickly, Soviet soldiers, again, should be delivered by transport aircraft.

For the Soviet government, this turn of events had a very definite resonance: on the one hand, an anti-government armed uprising took place at the southernmost borders, less than a hundred kilometers from the border Kushka, on the other - just acquired an ally, so loudly declaring a commitment to the cause of socialism, signed full of his helplessness, despite the very substantial assistance rendered to him. In a telephone conversation with Afghan leader Taraki 18 in March, Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers A.N. Kosygin, in response to complaints about the absence of weapons, specialists and officers, was inquiring: “It can be understood that there are no well-trained military personnel or very few in Afghanistan. Hundreds of Afghan officers were trained in the Soviet Union. Where did they all go? ”

The entry of Soviet troops was then determined to be an absolutely unacceptable decision, in which both the leadership of the armed forces and the party leadership of the country agreed. L.I. Brezhnev at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU rationally indicated: "We are now not befitting to get involved in this war." However, the Afghan authorities were assisted by all available measures and methods, first of all, by urgent deliveries of weapons and military equipment, as well as by sending advisers down to the highest rank, engaged not only in preparing the local military, but also in direct development of operational plans and guidance in struggle against the opposition (their level and attention to the problem can be judged from the fact that, to assist the Afghan military leadership, the Deputy Minister of Defense Oysk, Colonel-General IG Pavlovsky). To ensure the urgency of military deliveries, BTA was involved, especially since there was a direct government reference to this point, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU was voiced by the words of A.N. Kosygin: "To give everything now and immediately." The long-term transport aviation marathon began, without a break that lasted more than ten years later. For the most part, with planned deliveries, equipment, ammunition, etc. were supplied from warehouses and storage bases, often it had to be taken directly from the parts, and, if necessary, from the factories. It turned out that transport aviation played a crucial role not only in deliveries and supplies - its presence was somehow projected onto almost all events of the Afghan company, which makes it appropriate not only to transfer flights, cargo and destinations, but also a story about related events private character.

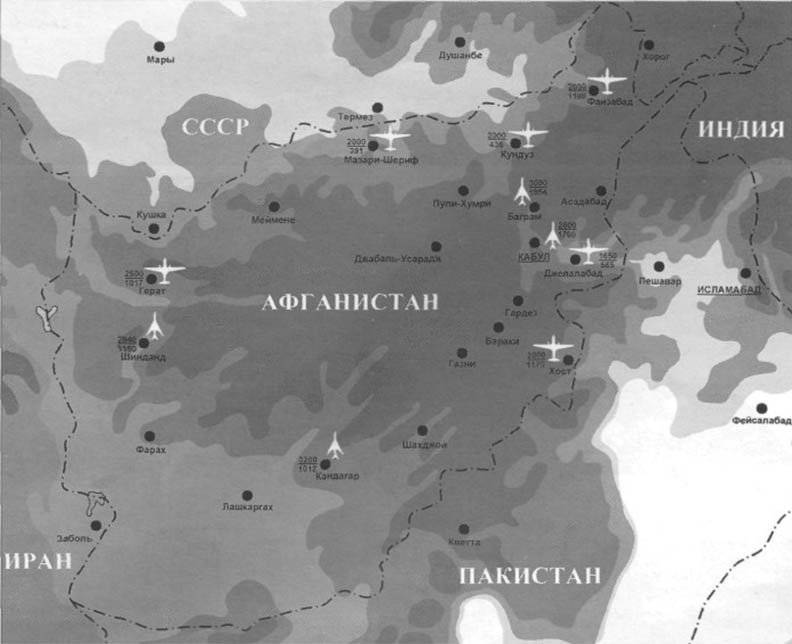

The special role of the An-12 in flights to the Afghan direction was dictated by their very predominance in the BTA line: by the end of 1979, aircraft of this type made up two-thirds of the general fleet - An-12 had 376 units in ten air regiments, while the newest IL-76 was more than half as much - 152, and An-22 - just 57 units. First of all, the crews of local air transport units located on the territory of the Turkestan military district — the 194 military transport regiment (paratrooper) in Fergana and the 111 separate air regiment in Tashkent at the district headquarters where An -12 was the most powerful technique. The aerodromes of their home base were closest to the “destination”, and the goods delivered to the Afghans after a couple of hours were already at the recipient. For example, X-NUMX of March made An-18 flights from Tashkent to the airfields of Kabul, Bagram and Shindand, the following days mainly operated IL-12 and An-76, carrying heavy equipment and armored vehicles, but 22 in March four An-X arrived from Bagram. -21, and from Karshi - another 12 An-19 with weights.

The problem with Herat with the military assistance provided was finally resolved by forces of the Afghan commando and tank crews transferred to the city. The city remained in the hands of the rebels for five days, after a series of air strikes, the rebels scattered and by noon 20 in March, Herat was again in the hands of the authorities. However, this did not completely solve the problems - the Herat story was only a “wake-up call”, testifying to the growth of the opposition forces. In the spring and summer of 1979, armed attacks swept the whole of Afghanistan - it didn’t take a few days for reports on the next foci of insurrections, the seizure of villages and cities, uprisings in garrisons and military units and their transition to the counter-revolution. When they gained strength, the opposition forces cut off communications to Khost, blocking the center of the province and the garrison there. Given the overall difficult situation on the roads, which are extremely vulnerable to enemy attacks, the only means of supplying the garrisons was aviation, which also guaranteed prompt resolution of supply problems.

However, with an abundance of tasks, the own forces of the Afghan transport aviation were quite modest: by the summer of 1979, the government air forces had nine An-26 aircraft and five piston Il-14 aircraft, as well as eight An-2 aircraft. There were even less trained crews for them - six for the An-26, four for the Il-14 and nine for the An-2. All transport vehicles were assembled in the Kabul 373 transport regiment (tap), where there was also one aerial surveyor An-30; Afghans somehow got it for aerial photographing of the terrain for cartographic purposes, but for the original purpose it was never used, it was mostly idle and was lifted into the air exclusively for passenger and transport traffic.

Civilian aircraft Ariana, which operated on foreign flights, and Bakhtar, which served local routes, were also involved in military transport, but they did not solve the problems due to the limited fleet and the same not very responsible attitude.

On this score, Lieutenant Colonel Valery Petrov, who arrived in 373 th for the post of adviser to the regiment commander, left colorful remarks in his diary: “Flight training is weak. Personnel preparing to fly unsatisfactory. They love only the front side - I'm a pilot! Self-criticism - zero, self-esteem - great. Flight-methodical work must start from zero. Unassembled, they say one thing in the eyes, make another for the eyes. Work go extremely reluctantly. I estimate the state of the technology entrusted to me with a plus. ”

In relation to the materiel chronic, it was plainly not carried out the preparation of equipment, violation of the regulations and frankly devil-may-care attitude to the maintenance of machines. The works were carried out for the most part carelessly, quite often turned out to be abandoned, unfinished and all this with complete irresponsibility. As usual, aircraft with malfunctions, tools and equipment forgotten here and there, as well as frequent theft from the sides of accumulators and other things needed in the household, were the usual thing to do, and the aim of putting the cars under guard was not so much protection from forays of the enemy, how much from the theft of their own. One of the reasons for this was the rapidly developing dependency: with the ever-increasing and almost gratuitous supplies of equipment and property from the Soviet Union, it was possible not to care about any kind of thrifty attitude to the materiel. Evidence of this was the mass without regret that the vehicles were written off in malfunction and abandoned at the slightest damage to the vehicles (in the 373-m tap, four aircraft were broken by the careless pilot Miradin in a row).

The work on equipment, and even the performance of combat missions, was increasingly “re-trusted” to Soviet specialists and advisers, the number of which in the Armed Forces of Afghanistan by the middle of 1979 had to be increased more than four times to 1000 people.

The issue of transport aviation remained very pressing, since air travel along with road transport were the main means of communication in the country. Afghanistan was a fairly large country, the size of more than France, and the distance, by local standards, were rather big. As a digression, it can be noted that the conventional wisdom that there was no railway transport in Afghanistan was not quite true: there was a formal way, though the entire length of the railway was five or so kilometers long and it was an extension of the Central Asian railway line stretched from the border Kushka to the warehouses in Turagundi, which served as a transit point for the goods supplied by the Soviet side (although the “Afghan railway workers” were not there, and the local people were busy except that as movers).

The leading role in transportation was taken by motor transport, which was privately owned by 80%. With a general shortage of state-owned vehicles, the usual practice was to attract the owners of the Burbuhek, whom the state hired to transport goods, including the military, good for good baksheesh who were ready to overcome any mountains and passes and make their way to the most distant points. The supply of military units and garrisons privately, as well as the presence of a private transport department in the government dealing with state-owned problems, was not quite common for our advisers.

The established procedure for resolving transport issues was quite satisfactory in peacetime, but with the aggravation of the situation in the country turned out to be very vulnerable. There was no assurance that the cargo would reach its intended purpose and would not be looted by the Dushman troops. Wielding on the roads, they impeded transportation, took away and destroyed sent goods, fuel and other supplies, burned recalcitrant cars, because of which intimidated drivers refused to take government orders and military supplies. Other garrisons sat unattended for months, and the starving and imprisoned soldiers scattered or passed on to the enemy and the villages got to him without a fight. Indicative figures were cited by Soviet advisers under the Afghan military department: with the full size of the Afghan army in 110 thousand people in the ranks by June 1978, there were only 70 thousand soldiers, and by the end of 1979, their numbers were completely reduced to 40 thousand, their staffing - 9 thousand people.

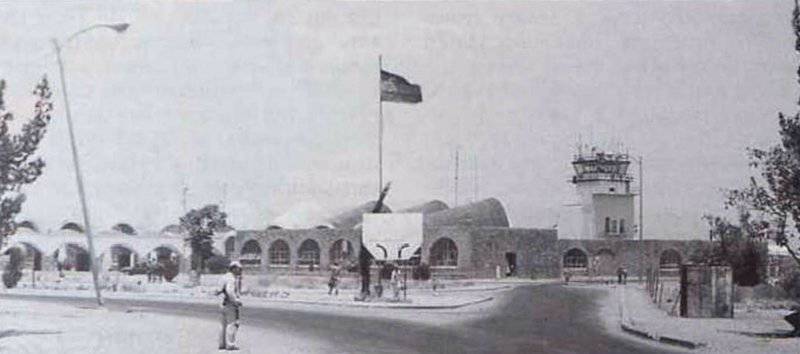

With the underdeveloped road network in Afghanistan, the role of air transportation became very significant. The country had 35 airfields, even if for the most part not of the best quality, but a dozen and a half of them were quite suitable for flights of transport aircraft. The airfields of Kabul, Bagram, Kandahar and Shindanda had very decent solid cast concrete runways and properly equipped parking lots. Jalalabad and Kunduz had asphalt strips; at other “points”, they had to work with clay soil and gravel pads. Doing without the involvement of special construction and road equipment, gravel was somehow rolled away a tank, sometimes fastened with watering liquid bitumen, and the runway was considered ready to receive aircraft. Somewhat protecting from dust, such a coating spread out in the heat and was covered with deep ruts from taxiing and taking off planes. The problems were added by highlands and complex approach patterns, sometimes one-sided, with the possibility of approach from a single direction. So, in Fayzabad, the landing approach had to be built along the mountain glen stretching towards the airfield, guided by the bend of the river and performing a steep right turn to reduce it to go around the mountain blocking the target of the strip. It was necessary to land from the first approach - right next to the end of the runway the next mountain towered, leaving no opportunity to go to the second round with inaccurate calculation.

The growing need for air travel was also dictated by the fact that air transport provided more or less reliable delivery of goods and people directly to remote locations, eliminating the risk of interception by the enemy on the roads. In some places, air transport at all became practically the only means of supplying the blocked garrisons, cut off by Dushman cordons. With the expansion of hostilities, the promptness of solving transport aviation problems was becoming invaluable, capable of quickly transferring the required parts to the warring units, be it ammunition, food, fuel or replenishment - in the war, as anywhere, the word “egg is dear to Christ Day” applies (although in Eastern the country more appropriately heard the remark of one of the heroes of the “White Sun of the Desert”: “The dagger is good for whoever has it, and woe to the one who does not have it at the right moment”).

There were plenty of tasks for the government transport aviation: according to the records of Lieutenant Colonel V. Petrov about the work of 373 th, only one day 1 of July 1980 by the regiment forces, according to the plan, were required to deliver a person 453 and 46750 kg of cargo by return flights taking wounded and oncoming passengers. One of the flights to An-30 immediately flew 64 people from local party members and military, heading to the capital for the People's Democratic Party plenum and crowded into the cargo compartment, even though the plane had no passenger seats at all. The delivery of army cargo and military personnel was interspersed with commercial and passenger traffic, since the local merchants, despite the revolution and war, had their own interests and knew how to get along with military pilots. The same V. Petrov stated: “Sheer anarchy: whoever wants, he flies, whoever they want, and that they carry”.

The helicopter pilot A. Bondarev, who served in Ghazni, described such carriages “in the interests of the population” in the most picturesque way: “They loved flying, because buses and cars were regularly robbed by outlaws. It is safer to get through the air, so a crowd of people willing to fly away gathered near the airfield barrier. Working with their fists and elbows, using all their cunning, the Afghans were bursting closer to the plane. Then the soldier from the airport guard gave a line over their heads. The crowd rolled back, crushing each other. The order was restored. The Afghan pilot recruited passengers for himself and led them to the landing, having previously checked things for ammunition, weapons and other things forbidden. What I found out - confiscated, the weapons that many had were supposed to take and were put in the cockpit. The most annoying and those who strove not to pay were denied the right to fly and, having received a kick, were removed from the airfield. Others burst on board, as if mad. I saw this only in the movie about the twenties, how people storm the train: they climb over their heads, push away and beat each other, push out of the cabin. Passengers they took, how much will fit. If too much was stuffed, then the pilots brought the number up to the norm, throwing out the extras along with their huge suitcases. About the suitcases are a special conversation, they must be seen. Afghan suitcases are made of galvanized iron and locked with padlocks. And the dimensions are such that the Afghans themselves can live in it or be used as a shed "

Lt. Gen. I. Vertelko, who arrived in Afghanistan for the Office of the Border Guards, where he was deputy chief, once had to use passing Afghan An-26 to get from Kabul to Mazar-i-Sharif. The general described the flight quite vividly: “As soon as I boarded the plane, the hatch slammed shut behind me and I felt like a little bug in a shark's belly. By the characteristic "flavors" and slippery floor I realized that before me there was a beast being transported here. When the plane lay down on the course, the cockpit door swung open, a young Afghan pilot appeared on the threshold and began to say something, waving his arms. It seemed to me that the Afghan demands "Magarych" for the service rendered. Running my hand into the inner pocket of my jacket, I took out a pair of brand new, crispy, “Chervonets” paint that still smelled. My "reds" disappeared into the hands of an Afghan, as if by magic, and he, putting his hands to his chest in a gesture of thanks, said the only word: "Bakshish?" - "No, - I say, - a souvenir." Although he probably had one hell, that baksheesh, that souvenir, the main thing - money in your pocket. As soon as the door closed behind this “gobsek”, another pilot appeared on the threshold. Having received “their own” two gold coins, he, in broken Russian, invited me to enter the cabin, crossing the threshold of which I found myself under the gun of five pairs of brown attentive eyes. In order to somehow defuse the lingering pause, I open my small traveling suitcase and start handing the contents to the left pilot (the right one is holding the steering wheel): a few cans of canned food, a stick of sausage, a bottle of Stolichnaya. From the wallet, I grabbed all the cash available there. Accidental coincidence, but also to those who did not present it earlier, got two gold pieces. The pilots cheered up, started talking at once, confusing Russian and Afghan words. It turned out that the one who speaks good Russian, graduated from college in the Union. ”

A relevant question is why, with such a demand for transportation, Afghan transport aviation was limited to the operation of lightweight aircraft and did not use An-12 - machines that were widespread and popular not only in the Soviet Union, but also in a dozen other countries? For the time being in aircraft of this type there was no particular need, and local conditions did not promote the use of a fairly large four-engine machine. The main nomenclature of cargo for air transportation during everyday maintenance of the army did not require a heavy aircraft: the most dimensional and heavy were the engines to the aircraft, which were units weighing up to 1,5-2 t, other needs were also limited to a level not exceeding 2-3 t. An-26 did quite well (just as in our urban transportation the most popular truck is the Gazel). In addition, the twin-engine car was extremely unpretentious to the conditions of local aerodromes, due to its low weight and having the capabilities of short take-off and landing, which was especially noticeable when working in high mountains and from short lanes (X-NUMX-ton take-off weight of the An-20 - this is not 26 tons from An-50!). Due to such advantages, An-12 could fly from almost all local aerodromes that were not suitable for heavier aircraft.

The An-12 was also unprofitable in terms of distance, here it is redundant, since most of the flights were operated on a “short arm”. Afghanistan, despite the complexity of the local conditions and the inaccessibility of many areas, was a “compact” country, where the remoteness of most of the settlements was a concept related to location rather than distance, due to which residents of many villages lying in the mountains near Kabul no messages with the city and in the capital have never been. Located in the east of the country, Jalalabad was only a hundred kilometers from Kabul, and the most distant routes were measured by distances in 450-550 km, covered by plane per flight hour. When it took tanks to suppress the Herati insurgency, it took a little more than a day to complete the march of the tank unit from Kandahar, which was at the other end of the country. In such conditions, An-12, capable of delivering a ten-ton load over three thousand kilometers, would constantly have to be driven half empty and for the Afghans it seemed to be the most suitable vehicle.

The situation began to change after the April events. The deeper the government and the army got involved in the struggle with the opposition, trying to extinguish the increasing armed uprisings, the more forces and means were needed for this. The suppression of insurrections, the organization of the struggle against the Dushman troops, the cleansing of the provinces and the supply of the provincial centers and garrisons needed means of supply and delivery. Meanwhile, these tasks, by definition, were answered by military transport aviation, the main purpose of which, among other things, was air transportation of troops, weapons, ammunition and materiel, ensuring maneuver of units and formations, as well as evacuation of the wounded and sick. In a specific Afghan environment, the range of tasks of transport workers was significantly expanded by the need to deliver domestic cargo, since small civil aviation was primarily engaged in passenger transportation.

Faced with problems, the Afghan authorities literally flooded the Soviet side with calls for help. The needs of Kabul were plentiful and plentiful, from food and fuel support to increasingly large-scale deliveries of weapons and ammunition, which were the real necessities of the revolutionary process.

With enviable persistence, the Afghan authorities demanded that the Soviet troops be sent to fight the rebels, but for the time being they were denied this. Such requests to the Soviet government were around 20, but both government officials and the military demonstrated sanity, pointing to the unreasonableness of engaging in someone else's unrest. Explaining the inexpediency of such a decision, the politicians listed all the pernicious consequences, the leadership of the Ministry of Defense pointed out that there was “no reason to deploy troops,” Chief of the General Staff N.V. Ogarkov spoke in a straightforward military manner: “We will never send our troops there. We will not establish order there with bombs and shells. ” But after a few months, the situation will change radically and irreparably ...

So far, 1500 trucks have been allocated to the Afghan allies as a matter of urgency to meet the urgent transportation needs; The corresponding instructions to the USSR State Planning Committee and Vneshtorg were given at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU 24 in May 1979, together with the decision on gratuitous deliveries of "special property" - weapons and ammunition, which would be enough to equip an entire army. However, the request of the Afghans to "send helicopters and transport aircraft with Soviet crews to the DRA" was again denied. As it turned out, not for long: the complicated situation in the country spurred Kabul rulers who insisted on a direct threat to the “cause of the April revolution” and openly speculated that “the Soviet Union could lose Afghanistan” (it is clear that in this case Afghanistan would immediately find itself in the clutches of imperialists and their mercenaries). Under such pressure, the position of the Soviet government began to change. In view of the obvious weakness of the Afghan army, the case tended to the fact that it would not be enough to supply weapons and supplies alone. The reason was the events around the blocked Khosta, for the supply of which at the end of May 1979, the main military adviser L.N. Gorelov requested the support of the forces of the Soviet VTA, temporarily transferring An-12 squadron to Afghanistan.

Since the voice of the representative of the Ministry of Defense joined the requests of the Afghans, they decided to satisfy the request. At the same time, in order to guard the squadron, in a restless situation, they decided to send a landing battalion.

Since the Afghans also experienced an acute shortage of helicopters and, especially, trained crews for them, they also decided to send a transport helicopter squadron to Kabul. Consent to satisfy the requests of the Afghan allies was an obvious concession: Kabul’s perseverance did not remain unanswered, while the Soviet side “kept a face”, distancing itself from engaging in Afghan civil strife and participating directly in hostilities; the sent transport workers are non-combat planes, and the landing battalion was assigned exclusively security tasks (besides, the fighters had to be located at the base of the base).

The implementation of the government order was delayed for two full months for reasons of a completely subjective nature. The equipment was immediately available: airplanes and helicopters were supplied from the aviation units located in the territory of the Turkestan military district, An-12 - from the Ferghana 194-th vtap, and Mi-8 - from the 280-th separate helicopter regiment deployed in Kagan under Bukhara . These parts were not far from the border and the equipment, together with the crews, could be at the destination on the very day. Difficulties arose with the personnel: since it was required to keep secret the appearance of Soviet military units in Afghanistan, even if of a limited composition, in order to avoid international complications and accusations of intervention (highly experienced AN Kosygin noted in this regard a bunch of countries will immediately come out against us, but there are no pluses for us ”). For these reasons, the planes should have looked civil, and transport helicopter helicopters, with their protective “military” color, should have been equipped with Afghan identification marks. The flight and technical staff decided to use from among persons of the eastern type, natives of the republics of Central Asia, so that they resembled the Afghan aviators outwardly, the benefit of those flying-technical form was completely Soviet-style and our “clothes” looked completely their own. The Afghans themselves suggested this idea - the country's leader Taraki asked to “send Uzbeks, Tajiks in civilian clothes and no one would recognize them, since all these nationalities exist in Afghanistan”.

Such precautions might seem like over-reinsurance - not so long ago, during the Czechoslovak events, a whole army was sent to the “fraternal country”, not really worrying about the impression made in the world. However, much has changed since then, the Soviet Union was proud of its achievements in the field of detente and its importance in international affairs, claiming to be the leader of progressive forces, and the third world countries gained some weight in the world and had to reckon with their opinion.

True, things were completely unsatisfactory with the personnel of the aviation professions. There were literally a few of them. Pilots were collected through DOSAAF, and already in March 1979, a special accelerated training kit for immigrants from Tajikistan was arranged at the Syzran Flight School. We also conducted an organizational recruitment in local departments of civil aviation, Dushanbe, Tashkent and others, attracting those who wanted an unprecedentedly high salary for a thousand rubles and a promotion to crew commanders after returning to the Civil Air Fleet. As a result of these measures, in the 280th helicopter regiment, it was possible to form an abnormal 5th squadron, nicknamed the "Tajik". Still, it was not possible to fully equip her with “national” crews, the six pilots remained “white”, from the Slavs, as well as the commander, Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Bukharin, for whose position they could not find a single Turkmen or Tajik. The navigator of the squadron was senior lieutenant Zafar Urazov, who had previously flown on the Tu-16. A good half of the personnel had no relation to aviation at all, being recruited for retraining from tankmen, signalmen and sappers, there was even a former submariner who flaunted naval black uniform. In the end, due to delays in the preparation of the “national” group, the full-time third regiment squadron led by Lieutenant Colonel A. A. Belov left for Afghanistan instead. The helicopter squadron, numbering 12 Mi-8s, arrived at the place of deployment in Bagram on August 21, 1979. For its transfer, along with technical staff and numerous aviation technical equipment, it was necessary to complete 24 An-12 flights and 4 Il-76 flights.

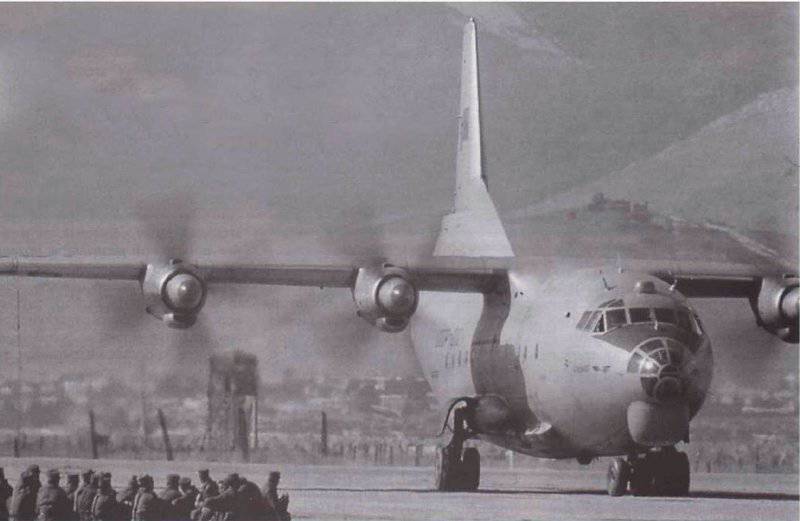

There were no such problems with the military transport squadron - An-12 with their "Aeroflot" marking looked quite decent and left for the place of business trip before the others. We even managed to observe the “national qualification” of the 194 transport workers, finding Lieutenant Colonel Mamatov for the post of squadron commander, who was later replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Shamil Khazievich Ishmuratov. Major Rafael Girfanov was appointed his deputy. A separate military transport squadron, named 200-I separate transport squadron (otae), arrived in Afghanistan already 14 June 1979 of the year. It included eight An-12 aircraft with crews of guards. Majors R. Girfanova, O. Kozhevnikova, Yu. Zaikina, Gv. Captain A. Bezlepkin, Antamonova N., N. Bredikhina V. Goryachev and H. Kondrushina. The entire air group was subordinate to the chief military adviser in the DRA and was intended to perform tasks at the request of the advisory apparatus in the interests of the Afghan state and military bodies.

This is how V. Goryachev, one of its participants, described the business trip, at that time the captain, the commander of the An-12 crew: “On June 12, our group (according to legend, it was a GVF detachment from Vnukovo airport) flew to Afghanistan at Bagram airfield . The group was selected to civil aircraft registration number (in large part the shelf planes had just such numbers). On these machines shot guns. All of them were equipped with underground tanks. Hence, from the airfield in Bagram, we carried out the transportation of personnel, weapons and other goods for the benefit of the Afghan army. In the summer, they flew mostly to the ringed Khost (14 times a week). Usually transported soldiers (and there, and back), ammunition, flour, sugar, other products. These flights for the hostages blocked by the rebels were very important. This is evidenced by the fact that the An-2 is designed for a maximum of 12 paratroopers. In reality, however, there in the airplanes it was "crowded" sometimes up to 90 Afghans. And they often had to fly standing. And, nevertheless, the commander of the garrison Khost was very grateful for such flights. The ability to change personnel favorably influenced both the physical condition and the morale of his subordinates.

It was assumed that the stay of the crews of the “Ishmuratov group” in Afghanistan would last three months. But then the term of our trip increased to six months. And then the introduction of troops began, and for a while there was no point in changing us, and indeed the possibilities. Often he had to fly to Mazar-i-Sharif, where from Hairatan on trucks delivered munitions. We then transported them all over Afghanistan. They also flew to Kabul, to Shindand, and to Kandahar. I had to visit Herat less often, and even less often - in Kunduz. The detachment did not suffer losses on both missions. ”

Placement of transport workers at the Bagram military base instead of the capital's airfield had its reasons. First of all, the same goals were being pursued to disguise the presence of the Soviet military who arrived with a fairly large number - two squadrons and a battalion of paratroopers from the Fergana 345 separate parachute regiment for their protection were under a thousand people, whose appearance at the Kabul international airport would inevitably attract attention and caused unwanted publicity. “Behind the fence” of the air force base they were far away from prying eyes, not to mention foreign observers and omnipresent journalists (in Kabul, then, more 2000 Western reporters were working, not without reason suspected of intelligence activities). It seems that they didn’t really know about the appearance of Soviet aviators and paratroopers in Afghanistan, since neither the press nor the western analysts of their presence had noted these months.

There were other considerations: at the beginning of August, the Kabul zone became a turbulent place - army troops launched armed uprisings in the capital garrison, and the opposition in the Paktika grew so strong that it defeated the government units there; They also talked about the upcoming campaign of the rebels in Kabul. Soviet Ambassador AM Puzanov these days even reported about the "dangers arising capture the airfield near Kabul." A well-defended military base with Bagram with a large garrison in this regard seemed to be a more reliable place. Over time, the aircraft for the military transport squadron had its own individual parking, located in the very center of the airfield, in the immediate vicinity of the runway.

As a result, it turned out that the first of the Soviet armed forces in Afghanistan were precisely the transport workers and the paratroopers who arrived to protect them. Although the patriotic-minded domestic press has long been arguing about the illegality of comparing the Afghan campaign with the Vietnamese war with the numerous arguments that international duty had nothing to do with the aggressive policies of imperialism, certain parallels in their history are said to suggest themselves. The Americans, even a few years before sending the army to Vietnam, faced with the need to support their military advisers and special forces with helicopter units and transport aircraft necessary to support their activities, to carry out logistics and other tasks. The inexorable logic of the war with the expansion of the scale of the conflict soon demanded the involvement of strike aircraft, and then strategic bombers.

In Afghanistan, events developed even more dynamically, and together with the entry of the Soviet troops, in a matter of months, front-line aviation was involved with the involvement of all its clans, from fighters and reconnaissance aircraft to the strike forces of fighter-bombers and front-line bombers immediately involved in combat work.

Transport squadron literally from the first days attracted to work. All tasks came through the line of the Chief Military Adviser, whose apparatus was increasing, and Soviet officers were already present in almost all units and formations of the Afghan army. Air transport provided a more or less reliable supply of remote areas and garrisons, because by that time, as the Soviet embassy informed, "under the control of detachments and other opposition groups (or outside the government's control) is about 70% of Afghan territory, that is, almost all rural areas ". Another figure was also called: as a result of the lack of safety on the roads, which “the counterrevolution chose as one of its main targets”, the average daily export of goods supplied by the Soviet side from border points to the end of 1979 decreased by 10 times.

The transport workers had more than enough tasks: in just one week of work during the exacerbation of the situation from 24 to 30 in August 1979, the X-NUMX of the An-53 flight was completed - twice as many as the Afghan IL-12 did. On the fly, An-14 was inferior in these months only to the omnipresent An-12, whose versatility allowed them to be used for communications with almost all aerodromes, whereas only ten of them were suitable for flying An-26.

Another tendency was gaining momentum - the desire of the Afghans to shift the solution of tasks to a stronger partner that appeared on time, which was confirmed by the continuing and ever-increasing requests for sending Soviet troops or at least militia forces that would take on the struggle against the opposition. The same character traits were noted when working with the Afghan military by Soviet instructors who drew attention to such behaviors of the local contingent (such “portraits” were compiled on the recommendation of military aviation medicine to optimize relations with national personnel): “Non-executive, attitude to service reduced when confronted with difficulties. In complex situations, passive and constrained, fidgety, deteriorating logical thinking, not independent and are looking for help. For seniors and those who depend on, they can be courtesy and offer gifts. They like to emphasize their position, but they are not self-critical and not independent. Prone to speculation things. " It is not difficult to notice that this characteristic, related to the trained military personnel, fully described the activity of the “leadership group” that came to power in the country.

Meanwhile, “revolutionary Afghanistan” was increasingly turning into ordinary despotism. The massacre of dissatisfied and yesterday's associates, the growing number of refugees to neighboring Iran and Pakistan, and the ongoing insurrections in the provinces have become commonplace. Injustice and repression led to riots of the Pashtun tribes, militant and independent nationalities, who traditionally left the main state apparatus and the army, and now for many years became the mainstay of the armed resistance, the mass character of which adds a large part of the country's population (in those the traditions of the Pashtuns never paid taxes, retained the rights to own weapons, and a good third of the men were permanently members of tribal armed groups). In response, authorities resorted to bombardments of recalcitrant villages and punitive actions of troops in previously independent Pashtun territories.

“The Revolutionary Process” in Afghanistan went its own course (readers will surely remember the popular song on our radio “There is a revolution in the beginning, there is no end in the revolution”). As a result of the aggravation of discord between recent colleagues in October 1979, the recent leader of the revolution Hyp Mohammed was eliminated Taraki The PDPA General Secretary, who considered himself to be a global figure, is no less than Lenin or at least Mao Zedong, was not saved by merit and self-esteem - yesterday's associates choked him with pillows and did not spare the family imprisoned.

On the eve of the protection of Taraki in Kabul, were going to transfer the "Muslim battalion" Major Halboeva. The commandos were already on the planes when the command came on the rebound. The authorities still hoped to resolve the Afghan crisis local media, relying on the "healthy forces" in the PDPA. However, just a couple of days later, Taraki was deprived of all his posts, charged with all mortal sins and imprisoned at the suggestion of his closest party comrade, the head of government and minister of war Amin. The paratroopers were again tasked to fly out to rescue the head of a friendly country, however, Amin prudently ordered that the Kabul airfield be completely closed on September 15. In response to an appeal to the chief of the Afghan General Staff, General Yakub, about receiving a special ship with an amphibious group, he replied that Amin was given the command to shoot down any aircraft that arrived without agreement with him.

Hafizullah Amin, who took power into his own hands, was a cruel and shrewd figure, continued to praise the Soviet-Afghan friendship and, not really trusting his own environment, he again expressed his wishes about the deployment of troops of the Soviet Army to Afghanistan (as the subsequent events showed, he succeeded - on his own head ...). Insisting on sending the Soviet troops, it was increasingly argued that the unrest in the country was inspired by the foreign intervention of the reactionary forces. Thus, the conflict acquired an ideological tinge, and the concession in it looked like a loss to the West, all the more inexplicable because it was about losing a friendly country from the USSR’s inner circle, with the frightening prospect of the appearance of omnipresent Americans with their troops, missiles and military bases. This picture fully fit into the dominant scheme of the confrontation between socialism and aggressive imperialism, the expansion of which across the globe was a popular theme of domestic propaganda, political posters and cartoons.

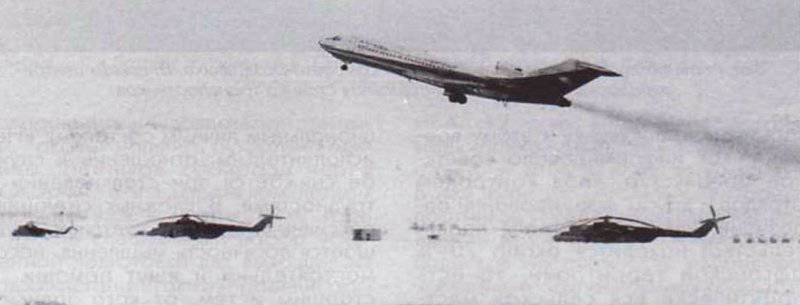

Reports of Amin's contacts with Americans were added to the fire. Even Amin’s sudden refusal to use a Soviet-made personal aircraft, in exchange for which the USA bought a Boeing-727 with a hired American crew, was considered evidence of this. The very appearance of American pilots and a technical group at the capital's airfield caused alarm - there was no doubt that under their guise secret service agents were hiding. Amin hurried to explain that this aircraft was received against previously frozen deposits in American banks, this is a temporary matter, Boeing will soon be leased to India, and the Afghan leadership, as before, will use Soviet aircraft. One way or another, the suspicions about Amin intensified and the decisions made on his account directly affected both himself and the activities of the Soviet transport squadron.

Changes in the top of Afghanistan soon affected the attitude towards the Afghan problem. In the position of the Soviet leadership, the recent almost unanimous reluctance to get involved in the local strife has been replaced by the need to take power actions, helping the "people's power" and getting rid of odious figures in Kabul. People from the environment L.I. Brezhnev pointed out that the sensitive general secretary made the death of Taraki. Upon learning of the massacre of Taraki, whom he favored, Brezhnev was extremely upset, demanding decisive measures against Amin, who drove him by the nose. Over the next couple of months, the entire military machine was activated and a plan of measures was prepared to resolve the Afghan issue.

The base of transport workers in Bagram unexpectedly became involved in the events of big politics. It was she who was used when the implementation of the plan for the transfer of individual Soviet units and special groups to Afghanistan, provided for the case of the very "sharp aggravation of the situation."

Formally, they were sent in agreement with the requests of the Afghans themselves, with the aim of strengthening the protection of particularly important objects, including the airbase itself, the Soviet embassy and the head of state’s residence, others arrived without much publicity and with less obvious objectives.

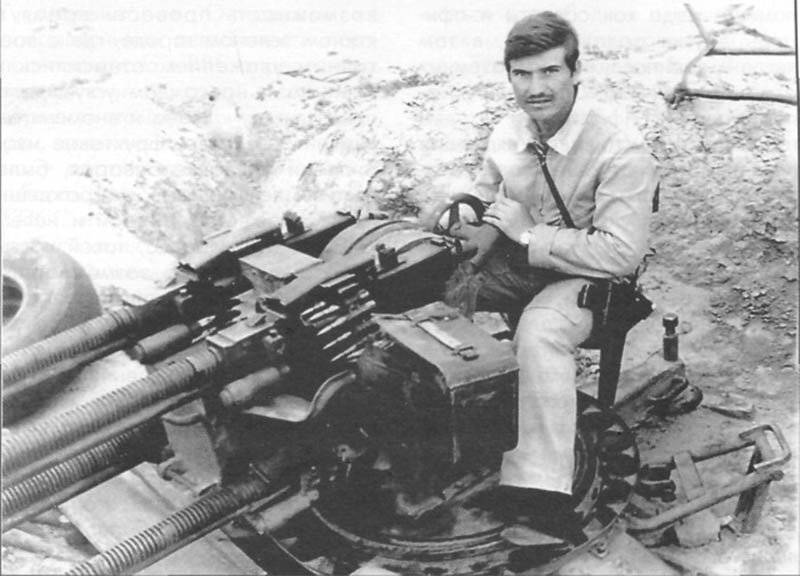

It was the base of transport workers that became the location for the special forces detachment, which was to play a leading role in the events that followed soon (by the way, Amin himself had time to suggest that the Soviet side "could have military garrisons in those places where she wished"). In subsequent events, transport aviation played a role no less important than the well-known actions of paratroopers and special forces. The redeployment of the "Muslim battalion" of the GRU special forces under the command of Major Habib Khalbaev was carried out on 10-12 in November 1979 of the year, transferring it from the airfields of Chirchik and Tashkent with BTA aircraft. All heavy equipment, armored personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles, were transported to the An-22 from the 12 th military transport aviation division; personnel, as well as property and supplies, including tents, dry rations and even firewood, were delivered to An-12. All officers and soldiers were dressed in Afghan uniforms and outwardly did not differ from the Afghan military. Uniformity was violated except by the commander of the anti-aircraft “Shilok” company, Captain Pautov, a Ukrainian by nationality, although he was dark-hair and, as Colonel V. Kolesnik, who led the operation, noted with satisfaction, “was lost in the general mass when he was silent”. With the help of the same An-12, the following weeks carried out all the provision of the battalion and communication with the remaining command in the Union, which more than once arrived in Bagram.

Based on the site, the battalion took up training in anticipation of the team to perform the "main task", for the time being not concretized. Two more units were redeployed to Bagram 3 and December 14 1979. Together with them, December 14 illegally arrived in Afghanistan, Babrak Karmal and several other future leaders of the country. Karmal, who was to become the new head of the country, was brought aboard the An-12 and secretly stationed at the Bagram air base guarded by the Soviet military. The new Afghan leader promised to attract at least 500 his supporters to help the special forces, for which transport aircraft to the base organized the delivery of weapons and ammunition. Only one came at his call ...

The given historical excursion into the prelude of the Afghan war seems all the more justified because in all these events transport aviation, which played the leading roles, was directly involved. With the decision to conduct a special operation, Colonel V. Kolesnik, responsible for it, in the morning of December 18 flew from Chkalovsky airfield near Moscow. The route flew through Baku and Termez; border Termez, instead of the usual transit airport of Tashkent, where the TurkVO headquarters were located, arose along the route due to the establishment of an operational group of the USSR Ministry of Defense in December 14, which was formed to coordinate all actions to deploy troops in Afghanistan and headed by the first deputy head General Staff Army General SF Akhromeev.

During the flight, there were problems with the equipment, which led to the search for another plane and the last part of the journey had to be overcome at the local An-12, which arrived late at night in Bagram. Two days before the order of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces was formed and brought into full combat readiness field control formed for entry into Afghanistan of the 40 Army. Its basis constituted units and positioned in the Turkestan and Central Asian military regions, preferably cropped, i.e. having a standard armament and equipment, but minimally manned (in essence, it was a peacetime logistics reserve, if necessary, staffed up to the regular strength with a call from soldiers and reserve officers). Naturally, the units and formations that were part of the army had a local “residence permit” from TurkVO and SAVO, and the personnel for their deployment were recruited from among the local residents through the recruitment envisaged by mobilization plans through the military enlistment offices. To this end, more than 50 thousands of soldiers and officers were called up from the reserve.

This option was directly envisaged by mobilization plans in the event of wartime or exacerbation of the situation, allowing for the rapid deployment of military units. According to the plan, immediately after the call-up of the military-required military specialties and their arrival at the nearby registered units, it was enough for them to receive uniforms, weapons and take up places on the equipment, so that they could almost immediately be ready to perform the assigned tasks.

Over time, a version was received that the soldiers of predominantly Central Asian nationalities were called upon to intentionally conceal the fact of the invasion of troops, “camouflaging” the appearance of an entire army in the neighboring country. For example, the book “War in Afghanistan” by American author Mark Urbain, considered to be a classic work on this topic in the West, says: “The Soviets were confident that the local call would keep in secret preparation for military operations.” Insight brings Western and domestic analysts: it suffices to note that the soldiers and officers, even if of the "eastern call", were dressed in Soviet military uniforms, which left no doubt about their identity, not to mention the TASS statement that followed a few days later aid to Afghanistan ”, however, with the excuse clause“ about the repeated requests of the DRA government ”. The formation of an army association based on units and formations of the local military districts was the most reasonable and, most obviously, speedy and “economical” way of creating the “expeditionary corps” of the Soviet troops.

In total, in the period from 15 to 31, December 1979 of the year, in accordance with the directives of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces, were mobilized and brought to full alert 55 formations, units and institutions included in the regular set of the 40 army. Bringing the troops into full combat readiness should be carried out in the shortest possible time, dictated, according to the instructions of the General Staff, by "glowing the military-political situation and by a sharp struggle for the initiative." At the time of the mobilization, the “first echelon” was the part of constant readiness that was on combat duty: border guards, command and control agencies, communications, airborne units and air forces, as well as all types of support. Inevitably, the responsible role was assigned to VTA, whose tasks included the provision and transfer of troops.

The decision to send troops to Afghanistan has been brought to the administrative board of Defense Minister at a meeting in December 24 1979 years.

As you know, the decision to bring troops into Afghanistan was communicated to the management team by the Minister of Defense at the December 24 1979 meeting. The next day, December 25 1979, the verbal instruction was confirmed by the directive of the USSR Ministry of Defense. But the lively work of the military transport aviation began in early December, when, according to the oral instructions of D. Ustinov, the mobilization of troops began, as well as the transfer of a number of units, primarily airborne units, to TurkVO. The airborne units, as the most mobile and combat-ready type of troops, had to play a leading role in the operation, having occupied key targets in the Afghan capital and central regions even before the bulk of the troops approached. December 10 was ordered to upgrade the Vitebsk 103 airborne division to increased readiness, concentrating forces and resources on loading airfields in Pskov and Vitebsk, December 11 to bring five BTA divisions and three separate regiments to increased readiness. Thus, the forces involved in the military operations were almost completely involved in the operation, including all five then-existing military transport associations - 3. Smolensk vtad in Vitebsk, 6-yu Guards. Zaporizhzhya Krasnosnamyonnay vtad in Krivoy Rog, 7-th vtad in Melitopol, 12-th Mga Krasnosnamyonnay vtad in Kalinin and 18-th Taganrog Red Banner vtad in Panevezys, as well as three separate regiment - 194-th in Fergana, 708-th in Kirovabad and 930-th in Zavitinsk (all - on An-12). When forming an air transport group, even aircraft from the instructor squadrons of the Ivanovo 610 training center were involved, from which they attracted 14 An-12 (almost all of them were based) and three IL-76 (from a dozen that were available).

In one of these compounds, the 12 th vadad, all the An-22 units in the number of 57 units were concentrated. The rest partially managed to re-equip the newest IL-76, which numbered 152, but not all of them were properly mastered by personnel. The main forces of the VTA, which accounted for two thirds of the aircraft fleet, were represented by the An-12.

In addition to the paratroopers, with the help of air transport it was necessary to make the transfer of control, communications and aviation-technical support groups.

Powered war machine all the time needed for the mass transportation transfer of thousands of people and pieces of equipment. The efficiency of the tasks required the use of many regiments of the military aviation aviation, whose crews had to go into combat work on the move. The involvement of a large number of aircraft in the operation and the sharply increased flight intensity were not without incident. At the intermediate landing at the border airfield Kokayty 9 December suffered An-12BK, out of order. The crew of Captain A. Tikhov from the Krivoy Rog 363 of the V-Tap performed the task of transporting the Su-7 aircraft for the Afghan Air Force from the repair plant. Having violated the established landing pattern at the airfield, moreover, in the approaching darkness of the night, the pilots began to approach it from a straight line and touched a two-kilometer-high mountain that was right along the course. The crew, as they say, was born in a shirt: having brushed belly across the top, having touched it with the propeller of the leftmost engine and leaving some details in place, the plane could still continue flying. Already on lowering, it turned out that the nose landing gear does not come out and knocks the oil out of the extreme right engine, which also had to be turned off. Landing was carried out on two main racks on the unpaved runway. Neither the cargo nor the people on board were injured, but the car was pretty damaged: the skin on the bottom of the fuselage was crumpled and torn, the hydraulic pipelines were torn, two engines were out of order. Repair work on the car required such a volume of labor, which lasted until the end of next year.

On the same day of December 9, while flying from Chirchik to Tashkent, another An-12AP crashed, on board of which, besides the crew, were two specialists who were flying to investigate the breakdown. In Tashkent, it was necessary to pick up representatives of the flight safety service from the army headquarters and move on to the scene. The entire flight to Tashkent with a length of 30 km was supposed to take a few minutes, and the crew did not need to gain any decent height. After the take-off made at night, the crew commander, Senior Lieutenant Yu.N. Grekov occupied the 500 m train, contacted the Tashkent airfield and began building an approach. Not very experienced pilot, just commissioned and flying with someone else's crew, did not have sufficient skills to fly in mountainous areas. Having made a similar mistake and violated the exit scheme from the departure aerodrome, he hurried with the installation of an altimeter on the landing aerodrome lying in the valley. Being sure that there is a reserve of height, while maneuvering while descending, already in Tashkent’s visibility, the pilot took the plane directly to one of the peaks of the Chimgan Range, which rose almost a kilometer. When colliding with a mountain, the plane fell apart and caught fire, all on board were killed in the crash. The plane and the crew belonged to 37-mu in the south of Ukraine. Together with the others on the eve, he was transferred to the Afghan border, and misfortune trapped him thousands of miles from his homeland ...

At the first stage of the entry of the Soviet troops, the task was to capture the airfields of Kabul and Bagram, taking control of administrative and other important objects, carried out by the airborne forces and special forces. As it was foreseen, in 15.00 Moscow time 25 December 1979 of the year began the transfer of airborne troops with a land landing on the airfields of Kabul and Bagram. Preliminary at a meeting of Soviet advisers gathered at the Kabul airport, a briefing was given and instructions were given to prevent the Afghan military units assigned to them from countering and hostile actions against the arriving Soviet troops (East is a delicate matter, although the top of the Afghan government asked for their entry, not local performances and armed attacks of army soldiers not engaged in big politics were excluded).

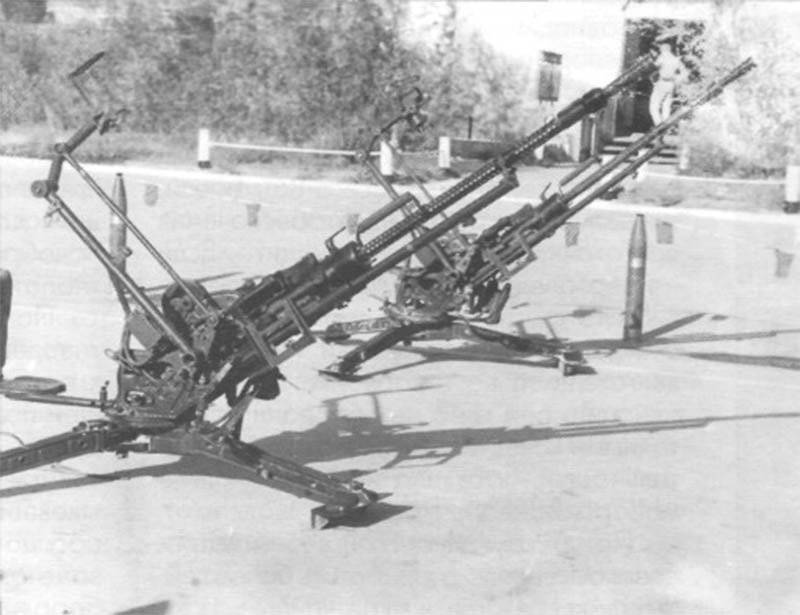

To prevent shelling of assault forces and landing aircraft at airfields, it was decided not to limit themselves to explanations among the Afghan military, but to take radical measures to remove sights and locks from anti-aircraft installations and to remove the keys to stored ammunition. Since relations with the Afghan soldiers were, for the most part, normal and trusting in nature, these actions were carried out without any special excesses. Among the military units of Bagram there was a military aircraft repair plant with a fairly numerous staff of Afghan soldiers (by the way, it was located next to the parking of Soviet transport workers). The adviser to his chief was Col. V.V. Patsko, says: "We, Soviet, at the plant were only two: I and adviser of the chief engineer. And now, through our advisory channels, we receive information that our troops have entered Afghanistan and that the task of disarming the personnel of this plant is set before us !!! Yes, they would have strangled us with bare hands. I call the director of the plant, an Afghan colonel. I explain to him - so, they say, and so. I understand that the order is stupid, but something must be done, somehow done. I looked, he darkened face. But he restrained himself. We were on good terms with him, humanly. He thought a little, then said: "You do not interfere, I myself." I gathered my officers, argued about something for a long time, then they all gave up their weapons. ” As a result, the landing of the aircraft with the landing force proceeded in accordance with the plan and without any incidents.

The first units of the 12-th separate parachute regiment were deployed to Bagram on An-345, then the paratroopers and equipment of the Vitebsk division began to arrive at the capital airfield. The paratrooper and poet Yury Kirsanov who participated in the operation described what happened in the following lines:

In the night a mighty caravan flies,

Over the people and technology stuffed,

Told us - fly to Afghanistan,

To save the people, Amin confused confused.

Gul sadivshihsya aircraft was clearly audible in the presidential palace Taj Beck, where Amin in the evening gave a reception. On the eve of the Soviet ambassador FA. Tabeev told Amin about the imminent introduction of Soviet units. Being confident that it was about fulfilling his own request, Amin elatedly told those present: “Everything is going fine! Soviet troops are already on their way here! ”The fact that special forces groups and paratroopers were already on the way, he was not mistaken, not realizing only that the events were not going according to the scenario he had planned and that he had only a few hours to live.

In total, the operation of the transfer of parts and divisions of the Airborne Forces required the 343 aircraft to be flown. The task took 47 hours: the first plane landed on December 25 on 16.25, the last one landed on December 27 on 14.30. On average, the landing of transport vehicles followed at intervals of 7-8 minutes, in fact, the intensity of the landing was much more dense, since the planes approached in groups and, after unloading, again went after the landing party. During this time, 7700 manpower, 894 units of military equipment and over 1000 tons of various cargoes, from ammunition to food and other materiel, were delivered to Kabul and Bagram. During the landing, the main part of the sorties was made by An-12, which made 200 flights (58% of the total), another 76 (22%) performed Il-76, giving an interesting coincidence of numbers - 76 / 76, and 66 - An -22 (19%). Sometimes these figures are referred to as the final results of the BTA’s work when troops are deployed, which is wrong: these data refer only to the transfer of the first echelon of paratroopers, communications and control units, after which the work of the BTA did not stop the delivery of personnel, equipment and logistics ensure continued without interruption for a day.

The predilection for free handling of numbers leads to some missteps: for example, N. Yakubovich in one of the Aviacollections issues devoted to the IL-76 aircraft, ranked all the work of the BTA aircraft in this operation exclusively to Il-76 transports, which looks frank by postscript - as can be seen from the above data, their real participation due to the above reasons was rather limited, and the main “burden” was delivered by An-12, which made almost three times more flights. The role of An-12 was explained primarily by their large number in the VTA grouping; on the other hand, a smaller payload compared to larger counterparts required for performing a typical task of transferring, for example, an amphibious battalion with standard armament to attract an additional number of airplanes and to perform a larger number of sorties.

In the following days, continuing the deployment of a group of troops, the transport workers were engaged in the logistics of the arriving forces and the delivery of new units and subunits, including aviation. The total strength of the 34 Air Corps at the beginning of the new, 1980, was 52 combat aircraft and 110 helicopters of various types. The work of the aviation group required the delivery of all the necessary ground support equipment, including all kinds of ladders, lifts and accessories necessary for servicing the machines, related equipment, as well as airmobile equipment for heat and power supplies. It was also necessary to support the engineering and technical staff, communications, controls, which was the task of the same BTA. Special vehicles and overall equipment of the support units from the OBATO (separate airfield-maintenance battalions attached to each aviation unit) went on their own, as part of military convoys.

In the period of its deployment, the aviation grouping was carried out mainly from the units of the 49 Air Army stationed on the Central Asian airfields - as can be seen, the formation of the aviation forces was supposed to be done with the same “improvised means” in number rather modest. Among them were the MiG-21bis squadron from 115-iap, stationed in Bagram, and the MiG-21Р reconnaissance squadron from the 87 orapp, deployed there, and the Su-17 squadron from the XNXX from the X-NXX, from the X-NXX in the X-NXX, and from the X-NXX, in the X-NXX, and from the X-NXX, in the X-NXX, in the X-NXX, in the X-NXX. also a squadron of MiG-217PFM fighter-bomber arrived in early January from the Chirchik 21 apb. One of their enumerations is able to give an idea of the scale of work on the delivery of everything necessary to support aviation activities (helicopter pilots in this regard were somewhat more independent, being able to deliver part of the means and technical personnel on their own).

After a few months, as the situation changed, there was a need to increase the air force, which required the involvement of the air forces of other districts (in the Armed Forces at that time, irrespective of the Afghan events, widespread reform of military aviation began, aimed at achieving closer cooperation with the army, during which the air armies of the front-line aviation, according to the Order of the Ministry of Defense of 5 in January 1980, were transformed into an air force of military districts, subject to the "red stripes" - the commander of the troops Amy districts). The air group redeployed to Afghanistan did not escape this fate; due to the expansion, it changed the status of the air corps to the Air Force title of the 40 Army, an aviation association of its own kind, since no other combined army had its own Air Force.

Among the other units in the 40 Air Force, the army immediately provided for the presence of transport aircraft (just as in the control of all military districts and groups of troops there were "their own" mixed air transport units). Its tasks were a variety of transportation, communications and support for the activities of the troops, the demand for which was constant and imperishable (with the peculiarity that in Afghanistan they were also added to direct participation in hostilities with the bombing assault, assault landings, patrols and reconnaissance missions ). To this end, when forming a military group, it was originally stipulated to give it a separate mixed air regiment, which included transport aircraft and helicopters. The corresponding directive of the Ministry of Defense appeared already on 4 on January 1980 of the year, in addition to which an order was issued by the Air Forces Main Command from 12 on January 1980, specifying the composition, staffing and equipment of the unit.

The formation of the 50-th separate mixed aviation regiment was carried out on the basis of the forces of TurkVO from January 12 to February 15, 1980, with the involvement of personnel and equipment from other districts. Helicopter units were the first to fly to Afghanistan, and by the end of March all the forces of the regiment moved to Kabul, where 50-th smallpox soon became widely known as “fifty dollars” (by the way, there was another fifty dollars in the army, the 350- th airborne regiment). The battle flag of the 50-th Aviation Regiment was awarded 30 on April 1980. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the activity of the regiment somehow affected virtually all the soldiers and officers of the army: while in Afghanistan, 50 thousands of people and 700 thousand tons of cargo were transported by 98 helicopters and helicopters only when carrying out transport tasks the regiment transported the entire army of one hundred thousand men seven times in a row!). 3 March 1983, the regiment’s combat work was awarded the Order of the Red Star.

In the early days, the BTA transport and landing operation was limited to disembarking at two central aerodromes, with the aim of ensuring the occupation of metropolitan administrative and key facilities, including the largest airbase, and other designated points were engaged in advancing ground-level echelon of troops and redeploying units on helicopters of army aviation to remote locations . The large volume of BTA tasks was also facilitated by the fact that the deployment of a group of troops took place during the winter months in Afghanistan is far from being the best, when roads and passes were covered with snowfall, followed by storming winds and storms — the famous “Afghan” gaining strength just in winter. Air transport in such an environment was not only the most expeditious, but also a reliable means of delivering everything necessary. Significant was the fact that the Soviet garrisons, for the most part, settled just near the airfields, which were the source of supplies and communications with the Union. Thus, in Kandahar, two cities were distinguished - the “Afghan”, which was the center of the same province of the same name, and the “Soviet”, which included army units and units located around the local airfield.

The whole special operation on taking the most important objects in Kabul took only a few hours from special forces and troops. The tasks were solved with minimal losses, although there were no overlaps caused partly by inconsistency, partly - by the secrecy of plans: at several sites the fighters fell under fire of their own units, and at the governmental palace Taj Bek, already taken by special forces, sent to support the Vitebsk the paratroopers did not recognize those of their own, shot them with armored personnel carriers and the case almost came to a head-on battle.

Babrak Karmal, who was in the position of the 345 Parachute Regiment, acted as the new leader of the country the next day, hurrying to announce that the change of power was the result of "a popular uprising of the broad sections of the population, the party and the army." It is curious that even today, other authors share a look at the events of the then Afghan ruler: in a recent publication by V. Runov “The Afghan War. Combat operations "claimed that the change of power in Kabul was carried out by a" small group of conspirators ", and the entry of Soviet troops served only as a" signal for a successful government coup "- a statement capable of causing considerable surprise to the participants in the events; No doubt, the author announced with a dashing stroke of the pen the “conspirators” of 700 of our soldiers and officers who participated in the storming and received military awards by a government decree of 28 of 1980 of April of the year. In the old days, the winners entered the capitals on a white horse, Karmal had to be content with the inconspicuous transporter An-12. Over time, when its star begins to decline, the Afghan ruler in search of refuge again will have to use an aircraft of Soviet transport aircraft.

In the meantime, the wounded during the assault of the fighters were taken to the Union on the Il-18, and in early January 1980, the entire personnel of the special forces battalion also flew home. The combat equipment was handed over to the paratroopers, the fighters and officers were loaded onto two transport workers who took off for Chirchik. It didn’t go without checking those returning to their homeland: it occurred to someone upstairs that the participants in the assault in the destroyed palace could find considerable valuables and subjected them to inspection, removing a couple of captured pistols, several daggers, a transistor receiver and a tape recorder, as well as stuck as souvenir local money - Afghani. Although in the Union colorful papers - “candy wrappers” were no good for anything, under the pretext that the money allowance in the “foreign business trip” was not issued, it was all handed over to a special department. The episode might seem insignificant, but it became a precedent for organizing a rather severe customs barrier at the airfields - the first thing that met the returning “internationalist fighters” in their homeland.

Unfortunately, the very beginning of the work of the “air bridge” confirmed the truth of the long-held truth that there is no war without loss. In the very first wave of 25 transporters in December, 1979 of the year crashed Il-76 of captain V. Golovchina, crashing into the mountain on the way to Kabul at night. In less than two weeks, An-7BP from the Ferghana 1980 th horn was injured when landing at 12 in January of 194, at the Kabul airport. As in the previous case, the cause of the accident was the error of the pilots when building the approach. The crew had little experience of flying in the mountains, although its commander, Major V.P. Petrushin was the pilot of the 1 class.

The accident occurred during the day in clear weather, when the destination airfield opened from afar. Nevertheless, in view of the proximity of the approaching mountains, the pilots began to build a landing maneuver too tightly, “squeezing the box”, because of which the aircraft set off on a landing course at a distance of 12 km instead of the established 20 km. Seeing that the plane was coming with a fair blunder, the pilot was confused, but did not go to the second round and continued to decline. Having flown almost the entire lane, the plane touched the ground just 500 meters from the end of the runway. The commander did not use emergency braking, and did not even try to evade the steering control from the obstacles rushing towards him. Having flown out of the runway to the 660 m, the plane hit the parapet and suffered serious damage: the nose strut was broken, the wing, screws and engines were damaged, after which the car flew into the SU-85 self-propelled gun. A collision with a twenty-ton armored obstacle was accompanied by especially grave consequences: an airborne captain Nelyubov and radio operator Sevastyanov suffered heavy blows upon impact, and in the crumpled bow cabin fatal injuries killed the navigator Senior Lieutenant M.L. Weaver (as usual, no one was tacked on the An-12 in flight, especially the navigator, who was uncomfortable working on a leash). The dead Mikhail Tkach, a recent graduate of the Voroshilovgrad Aviation School, from an early age dreamed of flying and in part was the youngest navigator, only the second year he came to the Ferghana regiment. The cause of the incident was called “mistakes in piloting technique of Major Petrushin, which were the result of his poor training, conceit and weak moral and psychological preparation, which was aided by the neglect of unstable pilot piloting techniques and surface preparation for flight”. Before this, the crew spent a week on a business trip, transporting the bodies of the first casualties brought by troops from Afghanistan, returning from which he went on his first and last flight to Kabul.

After the formation of the grouping of Soviet troops in Afghanistan, about 100 formations, units and institutions, which included almost 82 thousand people, were deployed in its structure. Already in February-March, the quick-change "guerrillas" of the Central Asian republics were replaced by personnel officers and conscripts (almost half of the original army had to be replaced). In addition to improving the combat capability of the units, these measures corrected the “national imbalance” of the army contingent: the professional level of the “reserves”, which was already low, was aggravated by their equipment - when transporting personnel, the crews of transport workers were amazed to see a wild, slanted and unshaven public in uniforms sticking with a stake overcoats of the war years and with PPSH machine guns taken from warehouse stores.