World history of cutting: Barrels

The first screw thread

In fact, there was no noticeable difference in the rate of fire. The roots of the error lie in the wrong comparison. As a result for a smooth-bore weapon, the normal rate of fire of a rifle is usually taken with record numbers for smooth-bore guns, and also obtained under ideal conditions (cartridges and a horn are seated on the table, the ramrod between shots is not removed in the bed, no need to aim). In the field, the usual gun did not do five or six, but only one and a half rounds per minute. The statistics of the Napoleonic Wars era showed that soldiers with ordinary guns lead only to 15 – 20% more frequent fire than choke hands.

Charging rifle rifle from the barrel was very difficult. To do this, a plaster (oily rag) was put on the muzzle and a bullet on the plaster, which was then driven into the barrel by a wooden hammer against the ramrod. To the edges of the projectile imprinted in rifling, had to make a lot of effort. The plaster, on the other hand, facilitated sliding, rubbed the trunk and prevented lead from cutting into rifling. It was impossible to overdo it. Going too deep, the bullet crushed the powder grains, which reduced the power of the shot. To prevent such cases, the cleaning rod was often supplied with a cross-guard.

The service life of the nozzle was also small. He usually held all 100 – 200 shots. The grooves were damaged by a ramrod. In addition, despite the use of the patch, they quickly leaded and filled with scale, and then erased when cleaning the barrel. To preserve the most valuable specimens, the ramrod was made of brass, and a protective tube was inserted into the barrel during cleaning.

But the main defect of such guns was the imperfection of the rifles themselves. The bullet kept in them too firmly and the powder gases did not immediately manage to push it, because the charge was burning in a minimal volume. In this case, the temperature and pressure in the breech breech of the rifles turned out to be noticeably higher than that of the smooth-bore guns. So, the trunk itself had to be made more massive to avoid a gap. The ratio of the muzzle energy to the mass of the guns was two to three times worse.

Sometimes the opposite situation occurred: the bullet kept in rifling too weakly and, picking up speed, was often torn from them. The oblong cylindrical bullet (experiments with one kind of ammunition were carried out from the 1720 year), in contact with the slits of the entire side surface, was too difficult to hammer into the barrel from the side of the barrel.

Another reason why rifle rifles have not been distributed in Europe for so long is their relatively low power. The "hard" progress of the bullet at the first moment of movement in the barrel and the danger of breaking from rifling closer to the muzzle did not allow the use of a large charge of gunpowder, which negatively affected the flatness of the trajectory and the destructive force of the projectile. As a result, the effective range of a smooth-bore shotgun was longer (200 – 240 versus 80 – 150 m).

The advantages of a smooth barrel were manifested only in the case of volley fire on group targets - a closed infantry formation or an avalanche of attacking cavalry. But this is exactly how Europe fought.

Angular cutting

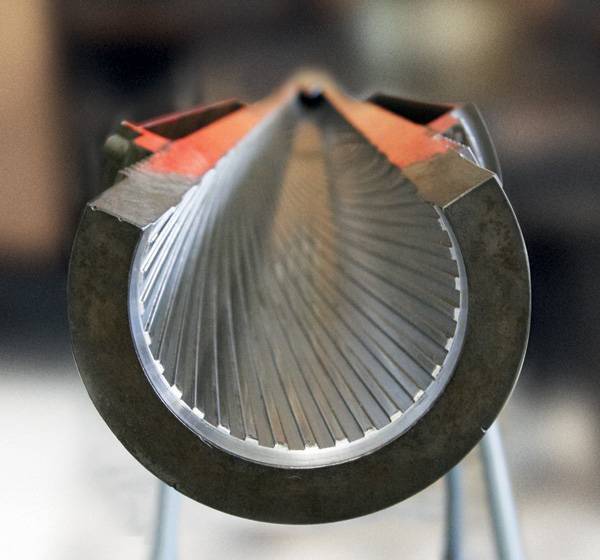

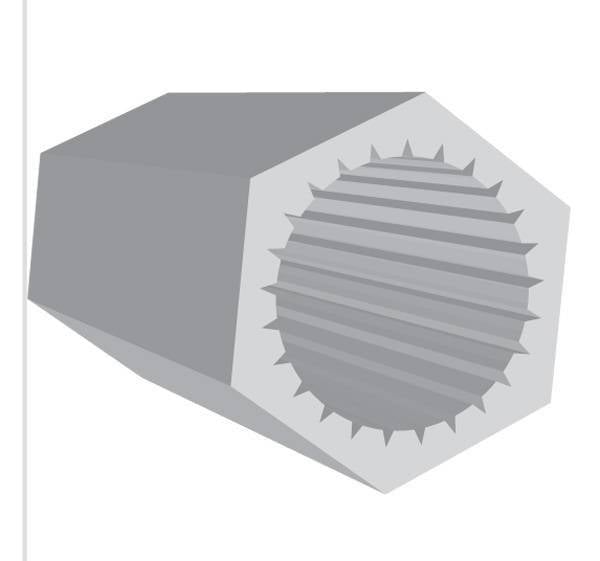

The first attempts to radically improve the rifling were undertaken in the XVI century. In order to improve the "grip", the inner surface of the trunks of the first fittings was completely cut. The number of grooves reached 32, and the course of cutting was very gentle - only a third or half of the turn from the treasury to the muzzle.

In 1604, gunsmith Balthazar Drechsler ventured to replace the now traditional, rounded, wavy cutting of a new, acute-angled. It was assumed that the small triangular teeth piercing the lead would hold the bullet stronger and it would not be able to break loose from them. In part, this was true, but the sharp edges cut through the patch, which protects the grooves from lead-in, and were more quickly erased.

However, in 1666, the idea was developed. In Germany, and a little later, rifles with very deep and sharp cuttings in the shape of a six-, eight- or twelve-rayed star became widespread in Kurland. Sliding along sharp edges, the bullet easily entered the barrel and held tightly into the grooves at their greatest steepness. But the deep “rays” did not respond well to cleaning, and it happened that they cut the lead shell in the barrel. It was still impossible to put a powerful charge of gunpowder under a bullet. Most often, star-shaped cuts were obtained by chinks — small-caliber rifles known from the 16th century for hunting birds. They were distinguished from other long-barreled weapons by a butt designed to rest not on the shoulder, but on the cheek.

Ribbed bullet holes

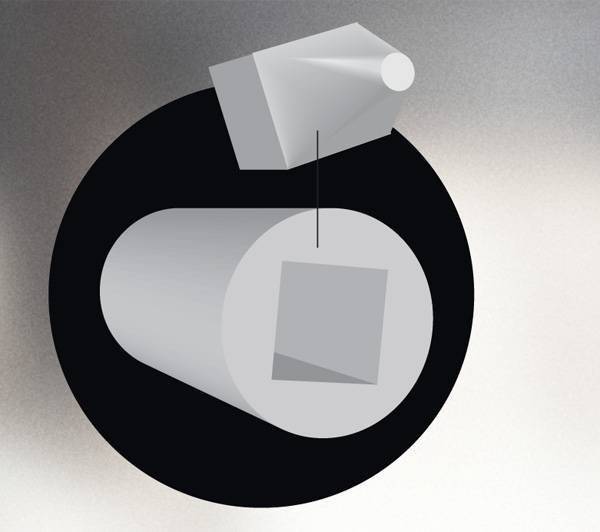

In 1832, Berner, a general of the Brunswick Army, designed a rifle that had a barrel of the usual caliber 17,7 mm with only two grooves 7,6 wide and 0,6 depth each. The union was recognized as a masterpiece, massively produced in the Belgian city of Luttich and was in service with many armies, including the Russian.

The Berner-like slicing has been known since 1725. The secret of the success of the union was in the pool, which was cast with a finished belt. It was not required to hammer in the grooves with a hammer. The ball, thickly plastered with grease, was simply inserted into the grooves and slid to the treasury under its own weight. The gun was charged almost as easily as a smooth-bore. The difference was in the need to replace two wads instead of a plaster or a crumpled paper cartridge. The first is for the oil not to wet the charge, the second is for the bullet not to fall out.

Criticism caused only shooting accuracy. As a rule, the "luteas" beat along with the best carbines of the usual cut. But there were frequent “wild” deviations: the bullet acquired too complex rotation, simultaneously twisting in cuts along the axis of the barrel and rolling along them, like in grooves. Later this flaw was eliminated by the introduction of two more rifling points (and bullets with two crossing bands) and the replacement of a round bullet by a cylindrical one.

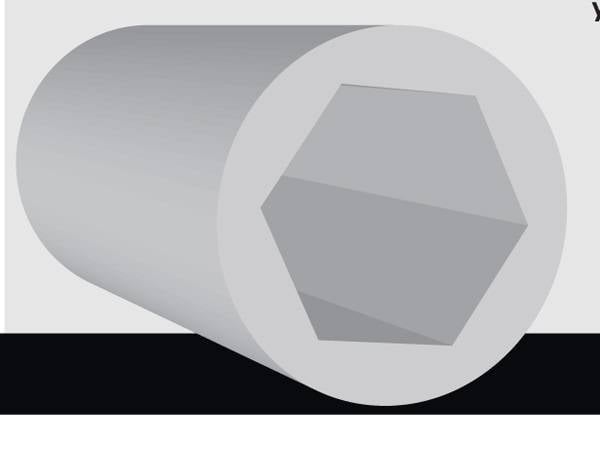

Polygonal rifling

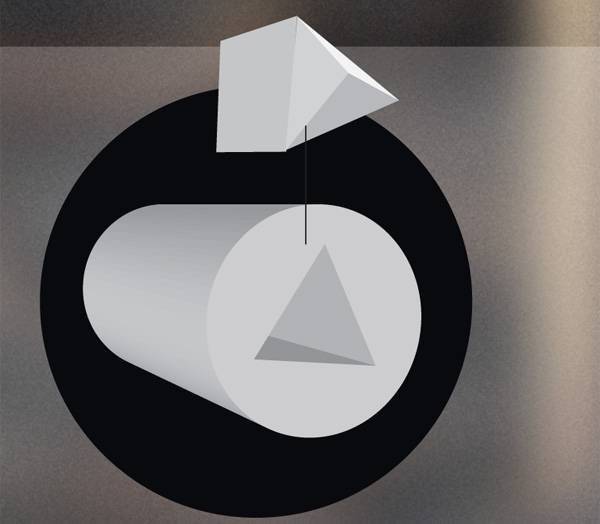

The barrel bore, the cross section of which is a circle with protrusions corresponding to the cuts, seems to be not only customary but also the most practical: it is easiest to drill a round hole. The Cossack rifle of the Tula master Tsyglei (1788 year), whose bore had a triangular cross section, seems all the more strange. However, experiments with triangular bullets were carried out before, since the 1760-s. It is also known that in 1791, a gun was tested in Berlin, the bullet to which was to have the shape of a cube.

Despite the boldness and extravagance of the plan, he was not devoid of logic. Polygonal rifling radically eliminated all the shortcomings inherent in rifles. The bullet of a triangular or square section was not required to flatten a ramrod. The power density of the weapon was also higher than that of a conventional choke, since the bullet went just as easily from the treasury to the muzzle. She could not get off the rifling. In addition, the trunk practically did not lead, was easy to clean and served for a long time.

The obstacles to the proliferation of weapons with polygonal rifling were mainly economic considerations. Forging a barrel with a faceted bore cost too much. In addition, the projectile in the form of a cube compared with the spherical had the worst ballistic performance and more complex aerodynamics. In flight, the bullet quickly lost speed and strongly deviated from the trajectory. Despite the obvious advantages of polygonal cutting, it was not possible to achieve better accuracy than when firing a round bullet.

The problem was solved in 1857 by the English gunsmith Whitworth, and in a very original way: he increased the number of faces to six. A bullet with “ready-made rifling” (i.e. hexagonal section) received a sharp tip. Whitworth's rifles remained too expensive for mass production, but were rather widely used by snipers during the war between the northern and southern states, becoming one of the first guns equipped with a telescopic sight.

The polygonal rifles proved to be the best, and already in the 19th century, ordinary round bullets began to be used to shoot from them. Overloading made lead fill the bore.

The proliferation of rifles with polygonal grooves, as well as the rapid progress of weaponry at the end of the nineteenth century, prevented the spread of innovation. During this period, the charge from the breech was widely used, smokeless powder appeared, the quality of the barrel steel radically improved. These measures allowed rifles with traditional rifles to completely drive out smooth-bore guns from the army.

Nevertheless, the idea of polygonal rifles is still being returned. The American Desert Eagle pistol and advanced automatic rifles have a barrel bore in the shape of a six-sided twisted prism, that is, classic polygonal cutting.

Traditional screw-cuts today dominate the rifled weapon. Polygonal cutting is much less common, not to mention the various exotic varieties.

It was available with five and four grooves. Used primarily by Thomas Turner (Birmingham) and Reilly & Co for short-barreled shotguns.

Beginning with 1498, the master Gaspar Zolner made barrels with grooves that did not inform the pivot of the rotational motion. The purpose of their introduction was to increase the accuracy of fire by eliminating the "reeling" of the bullet, whose diameter was usually much smaller than the caliber of the weapon. To score a bullet tightly interfered with soot - a real scourge of old guns. If the soot was pushed into grooves, it was easier to load the rifle with exactly the same caliber bullet.

Polygonal cutting is the main alternative to the traditional one. At different times, the number of faces-polygons varied from three to several dozen, but the hexagon is still considered the optimal scheme. Today, polygonal cutting is used in the construction of the American-Israeli pistol Desert Eagle.

Information