Austria-Hungary in the war: 1916 and 1917 campaigns. Deterioration of the empire

Having decided that Russia was no longer capable of conducting a serious offensive on the Eastern Front, the German General Staff decided to transfer the main blow to the Western Front, again trying to withdraw France from the war. Austria-Hungary focused its efforts on defeating the Italian army and removing Italy from the war.

However, in the summer of 1916, the Russian Empire presented an unpleasant surprise to the Central Powers. Contrary to the expectations of Berlin and Vienna, the Russian command decided to conduct a major offensive (meeting the wishes of the allies), which was very successful, although it did not lead to a fundamental change in the situation on the Eastern Front.

The frontal offensive operation of the South-Western Front of the Russian Army under the command of General Alexei Brusilov (May-July, 1916) led to the victory. The Austrian front was broken through. Russian troops occupied Lutsk, Dubno, Chernivtsi, Buchach. Our troops advanced from 80 to 120 km deep into enemy territory and occupied most of Volyn, Bukovina and part of Galicia. Austro-German troops lost 1,5 million people killed, wounded and captured (up to 500 thousand people were captured).

The combat capability of the Austro-German army was finally undermined, the Austrians held out only with the help of the Germans. Of the 650, the thousands of soldiers and officers who held the Habsburg Empire on the Russian front in the summer of 1916, in two months, 475 was lost to thousands of people, that is, almost three-quarters. The military power of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken. Within Austria-Hungary itself, defeatist sentiment intensified sharply.

To repel the Russian offensive, the German and Austrian commanders had to redeploy the Western, Italian and Thessaloniki fronts 31 infantry and 3 cavalry divisions, which eased the position of the Anglo-French troops on the Somme and saved the Italians from defeat. Under the influence of Russian success, Romania decided to take the side of the Entente. The strategic initiative finally moved from the Central Powers to the Entente countries.

However, a strategic breakthrough on the Eastern Front did not happen. The “disease” of the Russo-Japanese War played its role: the indecision of the Russian Stavka, the inconsistency of the actions of individual fronts and dullness, the lack of initiative of a significant part of the Russian generals. Brusilov rightly noted the “absence of the supreme leader” of the Russian army, since Emperor Nicholas II looked unconvincing in this role. The poor coordination of the strategy of the Entente powers played its role: Anglo-French troops launched an attack on the Somme only on July 1, when the first phase of the Russian offensive was already completed, and the Italians could not develop any noticeable activity in their direction until the beginning of August. Apparently, there is a fair grain in the opinion that the Western powers continued the strategy of "continuing the war to the last Russian soldier."

Brusilov himself wrote: “This operation did not give any strategic results, and could not give it, because the decision of the military council of April 1 was not implemented to any extent. The western front did not deliver the main attack, and the Northern Front had “patience, patience and patience” familiar to us from the Japanese war with its motto. The stake, in my opinion, did not in any way fulfill its purpose of controlling the entire Russian armed force. The grandiose, victorious operation, which could have been accomplished with the proper course of action of our supreme commander in 1916, was unforgivably overlooked. ”

Brusilovsky breakthrough forced Bucharest to side with the Entente. Romania, like Italy, has long traded, wishing to get the maximum benefit from the sale of its services. Having decided that the defeat of Austria-Hungary would make it possible to take away Transylvania from Vienna, the Romanian government went over to the side of the Entente. 17 August 1916 Russia, France and Romania signed a convention under which Bucharest, after winning, could expect to receive Transylvania, Bucovina, Banat and southern Galicia. 27 August Romania declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Romanian army invaded poorly protected Transylvania. However, Bucharest overestimated its strength and underestimated the enemy. The Romanian army had low moral qualities, was poorly prepared, there was no rear service (the railway network was practically absent), it was not enough weaponsespecially artillery. The command was unsatisfactory. As a result, even the Austrian army turned out to be stronger than the Romanian. The 1 th Austro-Hungarian army, with the support of the 9 th German army, quickly seized the strategic initiative and ousted Romanian troops from the Hungarian Transylvania. Then the Austro-Bulgarian troops under the command of the German General Mackensen attacked from Bulgaria. At the same time, the 3-I Bulgarian army, supported by the 11-I German army and Turkish units, launched an offensive in Dobrudja. The Russian command sent auxiliary troops under the command of General Zayonchkovsky to help the Romanians. However, the Russian-Romanian troops suffered a heavy defeat. Mackensen crossed the Danube, and the Austro-German-Bulgarian forces launched an offensive against Bucharest in three directions. 7 December Bucharest fell. The Russian command had to transfer considerable forces to the southern strategic direction and create the Romanian front, it included Russian troops and the remnants of the Romanian army.

Thus, Bucharest, hoping to profit at the expense of Austria-Hungary and thinking that it was a good time to enter the war, miscalculated. The Romanian army was unable to act independently and could not resist the Austrians, who were supported by the Germans and Bulgarians. The Romanian army suffered a crushing defeat, the capital fell. Most of Romania was occupied by the Central Powers. Russia had to allocate additional troops and funds in order to close the gap. On the whole, the entry of Romania into the war did not improve the position of the Entente. Russia received only a new problem. In addition, the Central Powers were able to strengthen their resource base at the expense of Romania. Germany and its allies received the oil of Constanta and the Romanian agricultural resources, which significantly improved the economic situation of the Central block.

On the Italian front, both sides planned to go on the offensive and achieve decisive results. In March, the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo took place, but the advance of the Italians did not lead to success. In May, the Austrians launched an offensive (the Trentine operation). The Austrians broke through the Italian defense, but by the end of the month their advance was exhausted. On the Eastern Front, Russian troops launched an offensive, and the Austro-Hungarian command had to transfer large forces to the East. The Italians in the middle of June launched a counterattack, the Austro-Hungarian troops retreated to their original positions. The bloody battle did not change the strategic situation at the front. In August, the Italians again launched an offensive against the Isonzo and achieved some success. Until the end of the 1916 campaign, the Italian army conducted three more (seventh, eighth and ninth) offensive at the Isonzo in September, October and November. But they all ended in vain.

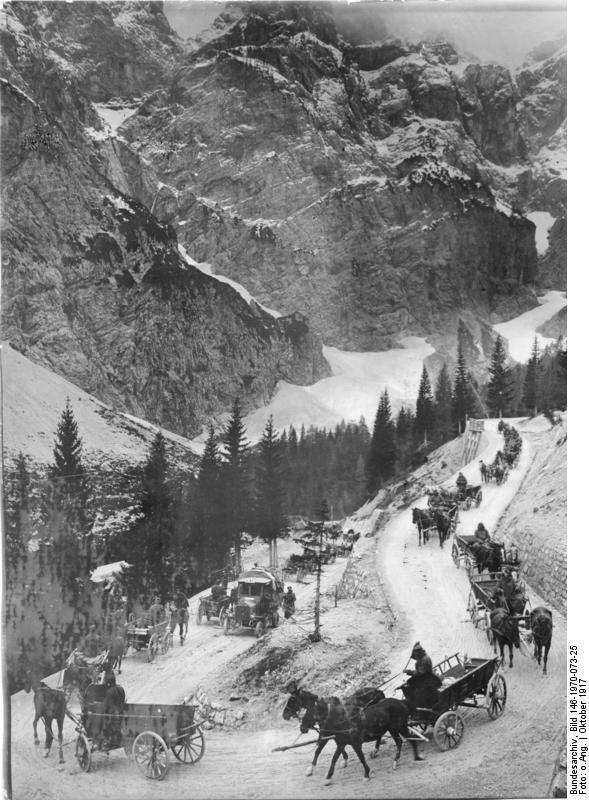

Austro-Hungarian highland artillery

1917 Campaign

In June 1917, the Russian army launched an offensive, achieved some success. But the offensive failed due to the catastrophic fall of discipline in the Russian army. After the revolution, the meaning of war for soldiers and a significant part of the officers was completely lost. In July, the Austro-German troops, meeting insignificant resistance, advanced through Galicia, and were stopped only at the end of the month. On the Romanian front, Russian-Romanian troops also initially succeeded, but in August the Austro-German forces launched a counter-offensive. However, here the Russian-Romanian troops have not yet decomposed and stopped the enemy.

On the Italian front in May, the Italians launched a new offensive on the Isonzo (already the tenth in a row). The Italian troops achieved some success, but failed to break through the defenses of the Austrians. In June, the Italians attacked in the Trentino area. Initially, the Italian Alpine arrows achieved success, but the Austrians launched a counterattack and rejected the enemy. The attacks of the Italian troops continued until June 25, but were unsuccessful and were accompanied by heavy losses. In August, the eleventh battle of the Isonzo began, which lasted until October. Italians have captured a number of important positions.

Thus, the Austro-Hungarian army retained the main positions, the Italians achieved local success, “biting” into the enemy defense. However, Austria-Hungary was already “shaken”, the army, having suffered huge losses (especially in the East), decayed. Society is tired of war. In Vienna, they began to fear that in the event of a powerful new offensive by the Italian army, supported by the British and French, the front would simply collapse, which would be the end of the empire.

The Austro-Hungarian command believed that the situation could be saved only by a powerful offensive, which is possible only with the help of the Germans. Unlike 1916, when the German General Staff refused large-scale support to the Austrians, assistance was rendered in 1917. A strike force was formed from eight Austrian and seven German divisions. From it created a new 14 th army under the command of the German General Otto von Belov. October 24 Austro-German troops launched an offensive. Austro-German troops broke through the Italian defense and captured Plezzo and Caporetto. The Italians hastily retreated, there was a panic. To save an ally, France and England began to hastily send reinforcements to Italy. It cheered the Italians. Emergency measures allowed to strengthen the defense. In November, the enemy was stopped on the Piave River, the front with the support of the Anglo-French forces stabilized.

Movement of convoy of Austro-Hungarian troops in the Isonzo Valley

New emperor

21 November 1916 died Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, who reigned 68 years (since 1848 year). His great-great-nephew Karl-Franz-Joseph becomes the new emperor under the name of Charles I. He was not prepared for such a high mission. Until the summer of 1914, the young archduke was in the shadow of Franz Ferdinand. And after his death, the emperor Franz Joseph did not dedicate his great-nephew to the intricacies of high politics. There are two main reasons. Firstly, the aged pessimistic emperor, apparently from the very beginning of the war, guessed its outcome and did not want the name of the young heir to be associated with the decision to start the war. This gave Karl the opportunity for a political maneuver.

Secondly, the highest civil and military bureaucracy of Austria-Hungary already lived its own life, pushing aside the monarch. Franz Joseph was old and passive, which allowed the highest dignitaries to play their game. The Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy was not interested in the fact that the new heir had the influence of his deceased predecessor. Therefore, the Archduke Charles from the very beginning of the war fell into a silent isolation. Karl could not get out of this situation on his own, as he was not a strong personality like his uncle.

In August, Charles 1914 was seconded to the General Staff, but had no influence on the development of military plans for the empire. At the beginning of 1916, the heir received an appointment to the Italian Front, where he headed the 20 corps. Karl managed to command the 1 Army, which in August 1916 entered the battle with the Romanians. On the Romanian front, the heir felt the taste of victory, but he also saw that Austria strongly depended on German aid. When in November 1916 a telegram came about a sharp deterioration in the health of the emperor, he departed to the capital to take power. By this time, he did not have time to acquire intelligent and loyal advisers and did not have a plan to transform the empire.

Emperor of Austria-Hungary Charles I (Karl Franz Joseph)

Rear

Hurray-patriotic moods disappeared quickly. Within a few months, it became clear that the war was total and would be delayed for a long time. Even long wars with Napoleon did not require so much strength and had breaks. It soon became clear that in such a war, the economic foundation of the country plays a crucial role. The front demanded a huge amount of weapons, ammunition, various ammunition, food, horses, etc.

Economically, the Habsburg Empire was ready for a short-term campaign in the Balkans against a weak adversary. But a protracted war destroyed Austria-Hungary. A huge stream of young and healthy men went to the front, the process of constant mobilization caused irreparable damage to the national economy. In January 1916, men of 50-55-age were declared military service. About 8 million people were drafted into the army, of whom more than half died and were injured. The number of working women and teenagers has grown. But they could not replace men. This led to a drop in production in such important industries as the extraction of coal and iron ore. Things reached the point that in 1917, the Austrian government obliged the church to hand in the bells to be melted down. The authorities conducted campaigns to collect scrap metal among the population, declared “rubber weeks”, “wool weeks”, etc. In 1917, in Budapest, due to a shortage of coal, all theaters, cinemas and other entertainment establishments were closed.

True, some industries that received military orders flourished. For example, the Czech shoe company Tomas Bata, which produced about 350 pairs of shoes per day before the war, by the year 1917 produced about 10 thousands of pairs a day, and the number of its employees grew almost 10 times over three years.

The decline in production occurred in agriculture. The further the war went on, the stronger were the contradictions between the two parts of the empire, since Hungary was better supplied with food and did not want to make additional deliveries to the Austrian Cloning. As a result, food shortages in the Austrian lands began to be felt from the first months of the war. The Austrian government has introduced cards on the most important types of food products, has established maximum allowable prices for most products. However, due to the crisis of agriculture, the shortage of food became more and more every year. A kilogram of flour in Zisleletania in the summer of 1914 cost an average of 0,44 crowns, a year later - 0,80, and in the summer of 1916 years - 0,99 crowns. And it was extremely difficult to buy it for this money, and on the black market (it appeared in 1915), a kilogram of flour could cost 5 times more. In the last two years of the war, price increases have become even more noticeable. At the same time, the rate of inflation was far ahead of the income growth of the vast majority of the population. Real wages fell by almost half in industry and by a third in employees.

At the end of 1916, the crisis of the Austro-Hungarian economy escalated sharply. However, until 1917, the population’s discontent was almost not manifested. From time to time there were strikes of workers (in enterprises that were engaged in military production, strikes were forbidden under the threat of a military tribunal), but the strikers generally put forward economic demands. The first two years were a time when the society got used to the war and still hoped that a favorable outcome was possible.

However, the ruling circles understood that the danger of a social explosion intensified by national sentiments was very high. In July, 1916, the emperor Franz Joseph told his adjutant: “Our situation is bad, maybe even worse than we assume. In the rear, the population is starving; this cannot continue like this. Let's see how we can survive the winter. Next spring, undoubtedly, I will end this war. ” Until spring, the old emperor did not live. But Charles came to the throne, too, convinced of the need for speedy peace.

To the world of Vienna was pushing the impending bankruptcy of the country. The point was not only in the weakness of the financial system of the empire, before the war the situation in it was fairly stable, but in the resource supply. Austria-Hungary did not have as many resources as its opponents. The Austro-Hungarian industry was weaker than the German industry and could not satisfy all the needs of the army and rear for several years. And external sources of supply of raw materials and goods were almost all cut off by the enemy. Austria-Hungary also lost the opportunity to obtain loans abroad to keep the economy afloat. It was not possible to negotiate loans with the United States, and in 1917, America sided with the Entente. It remained to hold domestic loans, which during the war years spent more than 20: 8 in Austria and 13 in Hungary. The Austrian krone was devalued throughout the war: in July 1914 for one dollar was given 4,95 crowns, at the end of the war more than 12 crowns for a dollar. Gold reserves were rapidly shrinking. During 1915 alone, the amount of gold reserves in monetary terms decreased by almost a third. By the end of the war, the gold reserves of 1913 were reduced by 79% compared to December.

At the same time, Austria-Hungary fell into not only military but also economic dependence on Germany. The economy of the Danube monarchy increasingly depended on Germany. Already in November 1914, German banks, with the support of the government, acquired Austrian and Hungarian government securities worth 300 million marks. Over the 4 of the war year, the amount of loans provided by the German Empire of Austria exceeded 2 billion marks, and Hungary received 1,3 billion marks.

Despite the revolution in Russia, which eventually led to the elimination of the Eastern Front, the participation of the Austrian troops in the occupation of Little Russia and stability on the Italian front did not improve the internal situation of Austria-Hungary. The war burden overwhelmed the stability of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Political situation

In the political and public life during the war in the Habsburg Empire "screwed the nuts." After the dissolution of the Reichsrat in March 1914, political life stopped. Even in Hungary, where parliament continued to work, Premier Tisa actually established an authoritarian regime. All the efforts of the empire were focused on achieving a military victory. Fundamental civil liberties — unions, assemblies, the press, correspondence secrets, and the inviolability of the home — were restricted; Censorship was introduced, and a special department was created, the Office of Supervision during the war, which was responsible for the observance of emergency measures. Restrictions concerned various aspects of life: from the ban to comment on the progress of military actions in newspapers (it was allowed only to print dry official reports) to toughening the rules for owning hunting weapons.

The struggle with the "unreliable" elements, which are primarily seen in the Slavs, began. The worse the situation at the front was, the more they looked for “internal enemies”. Austria-Hungary literally turned into a "prison of nations" before our very eyes. The Ministry of War has instructed to establish particularly careful supervision of the Slavic teachers called up for military service, primarily the Serbs, Czechs and Slovaks. They were afraid that they would conduct "subversive propaganda."

In the Czech Republic, Galicia, Croatia, Dalmatia, folk songs banned peacefully for hundreds of years were prohibited, children’s primers, books, poems, etc. were confiscated. Above the "politically unreliable" permanent surveillance was established, "suspicious people" were put in special camps. Moreover, these repressions were clearly unjustified. Despite the weariness of the war, the deterioration of life and restrictive measures until the death of Emperor Franz Joseph and the return to parliamentary life in Austria in the spring of 1917, there was no mass opposition. A strong and organized opponent of the monarchy arose only in 1917-1918, and the main reason for the sharp growth of the opposition was a military defeat.

Thus, the policy of the Austrian and Hungarian authorities towards the "underprivileged" peoples turned out to be disastrous and led to opposite results. “Tightening the screws” and repressions only strengthened the national movement, which for a long time was in a “sleeping” position.

This was most pronounced in the Czech Republic. Among Czech politicians, at the beginning of the war, a small group of separatists formed, who firmly stood for the destruction of the Habsburg empire and the creation of independent Czechoslovakia. They fled west through Switzerland or Italy. Among them was Tomas Masaryk, who led the Czech Foreign Committee created in Paris (later the Czechoslovak National Council) and will become the first president of Czechoslovakia. Among his assistants was E. Benes, the future second president of Czechoslovakia and one of the pioneers of combat aviation Slovak M. Stefanik. This committee was actively supported by France. In 1915, the Czech Committee stated that if earlier Czech parties sought independence of the Czech people within the framework of the Habsburg empire, now Czech and Slovak political emigration will seek independence from Austria-Hungary.

However, the influence of political emigration for the time being was small. In the Czech Republic itself was dominated by activists, members of activism, a movement that sought to achieve Czech national autonomy within the Hapsburg empire. Representatives of other nations during the war also emphasized their loyalty to the Hapsburg. But after the accession of Karl to the elite, liberal tendencies prevailed, and national movements quickly took the path of radicalization.

One of the leaders of the movement for the independence of Czechoslovakia Tomas Masaryk

The Austrian Germans were loyal to the dynasties and alliance with Germany. However, almost all influential Austro-German parties, except for the Social Democrats, also sought reforms. In 1916, the “Easter Declaration” was announced, in which it was proposed to create a “Western Austria”, which would include Alpine, Bohemian lands and Slavic Krajna and Goritsa. Slavic Galicia, Bukovina and Dalmatia were to receive autonomy.

At the beginning of the war, the Hungarian political elite almost all occupied right-wing, conservative positions, united around the Tisza government. However, a split gradually occurred. Liberals, nationalists and other traditionalists who relied on the aristocracy, the nobility and the big bourgeoisie, were opposed by a moderate opposition in the person of the Independence Party, which insisted on the federalization of the kingdom. However, until the death of Franz Joseph, Tisza’s position was unshakable.

Transylvanian Romanians were politically passive. The Slovaks, after a long period of Magyarization, also showed no political activity. Representatives of the Slovak emigration worked closely with the Czechs and the Entente. They chose between different scenarios: targeting Russia, Poland, or the Polish-Czech-Slovak Federation. As a result, she took up the line to create a common state with the Czechs.

The special situation was the Poles. The Polish national liberation movement was split into several groups. Right-wing Polish politicians headed by R. Dmowski considered Germany to be the main enemy of Poland and were on the side of the Entente. They believed that the Entente could restore the national unity and independence of Poland, even under the auspices of the Russian Empire. The Polish socialists headed by Yu. Pilsudski hated Russia and everything Russian and relied on Germany and Austria-Hungary. However, Pilsudski was a flexible politician and kept in mind the scenario that tsarist Russia would collapse, but the Central Powers would lose the war between England and France. As a result, the Poles fought on both sides of the front line. Another Polish political group was in Galicia. The Polish Galician aristocracy believed that the restoration of Poland at the expense of the Hapsburgs would be the best solution. But this scenario was opposed by Hungary, which feared the infusion of new Slavs into the Habsburg empire and, accordingly, the weakening of the dual principle.

In Berlin, after the Kingdom of Poland was conquered in the summer of 1915, they began to think about creating a loyal Polish buffer state closely connected with the German Empire. The Viennese court did not support such an idea, since pro-German Poland was shaking the Austro-Hungarian empire. However, Vienna had to yield. 5 November A joint Austro-German declaration was proclaimed on 1916, proclaiming the independence of the Kingdom of Poland. The definition of the borders of the new state was postponed for the postwar period. The Poles could not count on Galicia. On the same day, Vienna granted extended autonomy to Galicia, making it clear that this province was an inseparable part of the Hapsburg Empire. The Poles, who lived under German rule in Silesia and other areas, were also cheated, they remained part of Germany. New Poland was going to create only at the expense of Russia. At the same time, the Austrians and Germans were in no hurry to form the Polish kingdom. They could not agree on the candidacy of the Polish king, the Polish army was formed slowly. As a result, the Poles began to look towards the Entente, which could offer them more.

In the South Slavic lands, the situation was difficult. Croatian nationalists, whose core was the Croatian Party of Law, favored the formation of an independent Croatia - within the framework of the Hapsburg Empire or fully independent. Croatian nationalists claimed not only Croatia and Slavonia proper, but also Dalmatia and Slovenia. Their position was anti-Serb. Serbs were considered less cultural (Orthodox), backward and "younger" branch of the Croatian people. According to this theory, Slovenes were also recorded in Croats - so-called. "Mountain Croats". Croatian nationalists demanded the privatization of Serbs and Slovenes, copying the policy of Magyarization in Hungary.

The Serbian nationalists opposed the Croatian radicals. Their main goal was to unite all the southern Slavs within the “Great Serbia”. However, in order to oppose the Hungarian authorities, with their policy of Magyarization, gradually moderate Croatian and Serbian politicians came to the conclusion about the need for a union. The Croatian-Serbian coalition came to power in Dalmatia, then in Croatia, and advocated a trialist solution. However, the repressions of the authorities gradually transferred a large proportion of Slavic politicians to radical rails. Tensions increased in Croatia, Dalmatia and especially Bosnia. After the start of the war, the Slavs began to flee over the front line from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Banat and other provinces. Thousands of volunteers who fled from Austria-Hungary joined the Serbian army.

In 1915, in Paris, Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian politicians created the Yugoslav Committee, which was headed by the Croatian politician A. Trumbic (in 1918, he became Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). Later the committee moved to London. However, until 1917, there was no full-scale national liberation movement in the south of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Loyal political figures prevailed. Especially calm was in the Slovenian lands.

To be continued ...

Information