Short Mayo Composite. Composite aircraft system

Short Mayo Composite

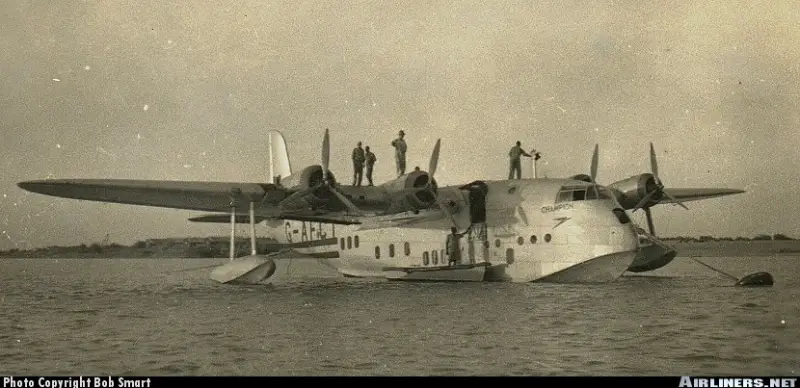

The world record for long-distance seaplane flight was achieved by a Mercury aircraft, the upper component of the Short Mayo Composite, which took off from the Tay estuary at Dundee on 6 October 1938.

The seaplane was mounted on the fuselage of the Maia flying boat to facilitate takeoff, allowing it to carry more fuel. The planes separated in the skies north of Dundee and the Mercury flew 6 miles to Alexander Bay, South West Africa.

Two experimental aircraft, the Mercury and the Maya, were built by Short Brothers Ltd. for Imperial Airways and are designed to transport mail over long distances without refueling..."

Have you heard about the collision over Brocklesby?

It is possible that you did not know about this name, but if I tell you history this incident, then you will say something like: “oh yes, I already knew about that!”

The Brocklesby collision occurred in the skies over the Australian village of the same name on September 29, 1940. That day, two Avro Anson patrol aircraft fought with each other. The turret of the lower aircraft was wedged into the root of the upper wing, and the fin and elevator touched the horizontal tail of the upper Avro Anson.

The engines of the plane on top failed - the propellers were blocked by the engine nacelle of the bottom one. However, the engines of the lower plane remained operational, due to which both planes, being in coupling, were able to stay in the air. The pilot of the lower Avro Anson and two navigators bailed out immediately after the collision, but the pilot of the upper one, Leonard Fuller, discovered that the two-plane structure could be controlled using flaps in conjunction with the lower aircraft's still functioning engine.

As a result, the pilot made a successful emergency landing in a field near the village of Brocklesby. All four crew members survived, and only one was injured. The aircraft were repaired and subsequently used in the service of the Australian Air Force.

And why did I remember this story today?

Composite aircraft systems

Moreover, our today's hero deliberately consisted of two aircraft, and his first flight took place two years before the collision over Brocklesby. I am sure that the story that will be discussed next will greatly surprise you, because such components aviation Even today the systems seem extremely unusual and difficult to operate, and even more so in the first half of the 20th century.

So, today we will talk about the British composite system of two aircraft - Short Mayo Composite.

Sikorsky S-42

In 1934, the high-speed aircraft Sikorsky S-42 appeared in the USA, which had quite good performance, being a four-engine “flying boat”. The symmetrical response from our British colleagues was logical.

Urgent measures were taken to catch up with the Americans who had taken the lead. First of all, the British Ministry of Aviation prepared a task for a high-speed seaplane that could significantly improve communications with the dominions: at that time, Great Britain was the strongest metropolis on Earth, which imposed obligations on providing logistics between the colonies. First of all, we are talking about remote Australia.

At the same time, the Empire Air Mail Program, formulated by Sir Eric Geddes, was born, according to which all “first-class” mail should be delivered within the empire by air. It is curious that in order for the program to satisfy the financial appetites of the British government, its support was required, including subsidies from the dominions, which became a big obstacle to the implementation of the plan. In accordance with these requirements, the new aircraft had to transport 24 passengers, 5 crew members and 1500 kg of mail at a speed of at least 210 km/h with a headwind of 60 km/h. The service life of the machine had to be at least 10 years.

Short, a well-known company at that time, responded to the government’s initiative. Their proposal was a four-engine “flying boat” S. 23. Imperial Airways immediately ordered 28 aircraft. The company's technical advisor at that time was Major Robert H. Mayo, who developed the specifications for the future Short aircraft. A contract was signed with the manufacturer for the amount of 1 pounds sterling - a huge amount of money at that time. Delivery of the first copy was expected on May 750, 000.

Another, but not the last customer was the Australian airline Qantas Empire Airways. This, by the way, was not provided for when organizing the Empire Air Mail Program plan.

The design work was led by Briton Arthur Goudge. Unlike previous sea-based airliners such as the S. 8 Calcutta and S. 17 Kent, the new aircraft was not a biplane, but a cantilever high-wing aircraft. Engine nacelles were installed directly in the wing. All this, by the way, was already on the competitor Sikorsky S-42. Four Bristol Pegasus Xc engines were chosen as the power plant. The model of the future airliner was carefully tested in a wind tunnel and a water channel.

The finished copy (serial number S. 795) was launched on July 2, 1936. It took two years to develop the vehicle. The new car was called the telling name Short Empire. The prototype received the tail number G-ADHL and the name Canopus.

On July 3, 1936, the Short company organized a sports festival. Pilot John Lankestor Parker had to demonstrate the seaworthiness of the new car during runs along the River Medway. However, the car behaved so obediently that Parker could not resist and lifted it into the air, holding the S. 23 in this position for 14 minutes.

Here I will interject and say that in such alliteration the story seems extremely strange. Uncoordinated flights, although rare in aviation, do occur sometimes. You don’t have to look far for examples: YF-16, U-2, A-12 - the first flights of these machines were unexpected for the creators and inconsistent. But if we analyze these situations, we can come to the conclusion that they were all more likely aviation incidents than full-fledged first flights. And in the case of the General Dynamics YF-16, the creator company, after the first unofficial flight on January 21, 1974, had to conduct the official first flight on February 2, 1974.

In the case of Short Empire, this was not the case, and this story seems to be even boasted about.

One way or another, official tests began the very next day, so the story of the unofficial first flight could really turn out to be an advertising brochure. They went very well, with almost no comments.

Serial production began on December 4, 1936. Like the prototype, production vehicles were produced at the Short plant in Rochester, Kent. Arthur Goodge, by the way, was also from Kent, but was born west of Rochester: in the city of Northfleet. The aircraft was successfully operated on long-distance routes - from Great Britain to South Africa and Australia.

We won’t dwell on the exploitation of Short Empire and will go straight to one fleeting story that plays a very important role in today’s story.

Transatlantic mail

Since the time when aviation became a more or less competitive type of technology, as soon as aircraft designers from different countries figured out how airplanes work and operate, attempts immediately began to fly an airplane across the Atlantic Ocean. Goal: to connect the Old and New Worlds, to establish communication not only with the help of ships.

We will not dwell in detail on the comparison with the history of Caproni Ca. 60 Transaereo, within the framework of which we would definitely need knowledge of the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, but let's immediately move on to the important.

Short S. 23 G-ADHM Caledonia and G-ADUV Cambria

In 1937, on the basis of the Short Empire, the possibilities of using the machine on the transatlantic line were explored. Two examples, G-ADHM Caledonia and G-ADUV Cambria, were modified (designated S. 23 Mk. III). Due to the reduction in the number of passengers, the flight duration increased to 20 hours. From July 5 to 6, 1937, Caledonia flew from Foynes Harbor (Ireland) to Botwood (Newfoundland), from there to Montreal and on to New York. I returned home the same way.

In total, as part of the tests, Caledonia performed three flights in both directions, Cambria - two. However, the planes flew without cargo. It was clear that the S. 23 would not cross the Atlantic with a payload.

Short S. 30

For this reason, a new modification was created - S. 30, with Bristol Perseus XII engines and a range almost doubled. Nine such aircraft were produced. For a short time they actually flew across the North Atlantic. In addition, two aircraft of the S. 33 modification were built with a more powerful Bristol Pegasus Xc engine.

The result is not considered a failure, but it was obvious that conceptual changes to the design were urgently needed. Otherwise, the decision to create an effective cargo aircraft could take many years, which was clearly not part of the plans of the monopolists in the field of medium-haul and long-haul flights Imperial Airways. At this stage, the only payload that such an aircraft could carry was fuel.

John Lankester Parker and Major Robert H. Mayo respectively

And one of those for whom the creation of a cargo aircraft capable of flying across the Atlantic Ocean while maintaining a large payload was a fixed idea was the already mentioned several times Major Robert H. Mayo. As the technical general director of Imperial Airways, he understood better than many others that the creation of a production aircraft that would connect North America and Europe was extremely important at the moment. Because humanity is developing, the need for fast communication is increasing more and more, and as a result, mail, which was very popular in those years, must be delivered in large quantities and quickly enough. Namely, demand gives rise to supply or, as in our case, the desire of aircraft designers to respond to this request in different ways.

In general, we can talk about the history of mail planes for a very long time and in some detail, but I will focus on one problem that is especially important for our history: international transportation.

Composite aircraft

At that time, in this formulation, this was not a problem: in September 1920, even an intercontinental flight had already been completed. The problem was in the transatlantic flight, because a lot of mail is also transported on this route, which is still delivered only by ship, which is very expensive and not fast.

Moreover, until aviation took some leadership in mail delivery, countries such as Great Britain and the United States relied on the most reliable transport companies and the best steamships to transport mail. The fastest transatlantic liners flying the British flag were called Royal Mail Ship. This emphasized that this ship was so reliable and prestigious that the crown itself trusted it to carry mail.

To speed up the mail delivery process, the two best German transatlantic ships, Bremen and Europa, were equipped with catapults from which a small seaplane could launch. When the liner approached the shores of the destination country, it was the mail that was sent forward. Thus, its delivery was accelerated by several hours.

From this one could conclude that similar requirements will be imposed on aircraft, but no. After the advent of this type of technology, airplanes became a very expensive and high-status mode of transport, in which only the richest people in society traveled. This is how the unwritten rule turned out that mail must be delivered as soon as possible, after all, a method of communication, but in critical circumstances (for example, in an accident), it may be lost, and the passenger, in which case, can wait, but he must reach your destination safe and sound.

As a result, the mail plane was subject to much less stringent safety requirements than the passenger plane. As a result, postal aviation developed according to laws different from passenger aviation.

The UK's Department of Trade began the creation of the future transatlantic aircraft by issuing strict requirements for the future machine: a passenger flying boat that can continue to fly confidently at only three-eighths of its maximum available power.

Simply put, a four-engine aircraft had to ensure the safety of its passengers with the complete failure of two engines and the cruising thrust of the remaining two. In this regard, the design of the seaplane was seen as another compromise, because if such an aircraft’s engines failed, it would be able to make an emergency landing on water, and there is a lot of it on planet Earth and there are clearly more of them than there are runways.

And even here, in matters of the design of a seaplane, on which the safety of the cargo on board directly depends, the division in favor of passenger cars is clearly visible to the naked eye. The latter must have a boat-like fuselage that is sufficiently seaworthy and safe even on large waves. At the same time, the mail plane could have a significantly smaller power reserve, and as landing devices it was allowed to install light floats, whose performance during a forced landing in a stormy sea left much to be desired.

In some cases, the mail plane, packed to capacity with cargo and flooded with gasoline, simply did not have enough power to take off into the air, so it had to take off from a catapult or using other external launch devices.

After the UK Ministry of Trade drew up a specification, from which all the requirements for the future aircraft were completely clear, the Ministry of Aviation took on its work, drawing up its own specification, with the characteristic number 13/33.

In fact, not much is known about the contents of this specification. Based on the title, we know that it was published in 1933, and what was to be built to that specification: a transatlantic aircraft designed by Robert Mayo.

And here, it seems to me, it’s worth revealing the cards and telling how, in Robert Mayo’s mind, the machine that would later go down in history under the name Short Mayo Composite should have looked like.

Short Mayo Composite

It has long been known that aircraft can sustain flight with a larger payload than is possible at takeoff. Robert Mayo was aware of this (depending on how you look at it) disadvantage or advantage of aircraft, and therefore proposed a very avant-garde, but extremely smart solution for delivering a large number of payloads on medium- and long-haul routes.

First of all, the previously mentioned Short Empire, with which he was already intimately familiar, was needed as a large carrier aircraft, on the back of which a small long-range seaplane could be mounted. Using the combined power of both, they would rise into the sky to lift the smaller one to operating altitude, after which separation would occur: the lower one would return to base, and the upper one would fly to its final destination. Equipped with only floats, the upper plane would carry mail, while the carrier would be capable of carrying a number of passengers, and, according to the previously mentioned unwritten law, it would be a “flying boat”.

The proposal was accepted by the Ministry of Aviation and Imperial Airways, who jointly awarded Shorts a contract to design and build such a composite aircraft system. The initiator of the idea, Robert Mayo, begins working with them.

On November 7, 1935, a large article was published in Flight magazine with an eloquent and intelligible title - “Composite Aviation System” (can also be translated as “composite aircraft”). It was written by an author who signed himself as S. M. Poulsen, and I saw the most understandable explanation of the purpose of creating such a machine from him. It sounds like this:

In addition, the article presents a sound analysis of the pros and cons of creating such a coupling. I encourage those interested to read it, but it is worth noting that I was only able to find a fragment, part of this article: the rest was simply not archived.

USS Akron and USS Macon

And the solution to the problem of the dependence of flight range on the number of payloads on board turned out to be truly ingenious. By that time, the airships USS Akron and USS Macon already existed, capable of carrying on board five Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk fighters at once, but the creation of two sufficiently large aircraft capable of separating directly in flight, while taking off in a composite state, only for the purpose of lifting one of them to a working height, no one had worked on it until that moment. And even after the successful creation of the Short Mayo Composite, the implementation of such a concept will remain extremely difficult, and not everyone will undertake its implementation.

Felixstowe Porte Baby, on the wing of which you can see a Bristol Scout fighter, and John Cyril Porte himself

And let’s go back a little to the phrase that no one had worked on composite aircraft systems before Short Mayo Composite.

Flying boat

It would be more accurate to say that practically no one, because on November 20, 1915, the Felixstowe Porte Baby aircraft, created under the leadership of John Cyril Porte, took off into the sky. It was a virtually undistinguished reconnaissance seaplane from the First World War, apart from its impressive dimensions, of course: length 19,21 m; wingspan 37,8 m; height 7,62 m; wing area 219,7 m². At the same time, 3 in-line piston engines Rolls-Royce Eagle VII V12 with a power of 345 hp. With. each, as a result of which the speed of the aircraft could reach 141 km/h. He could carry 3 Lewis light machine guns, one of which was in the nose, and the other two in the tail.

From November 1915 to 1918 it was the largest flying boat built and flown in the United Kingdom. But its peculiarity lay in something else: on its upper wing it could carry a Bristol Scout fighter.

The idea was to intercept German Zeppelin airships far out at sea, beyond the normal range of land-based or shore-based assets. Despite the successful first flight of the coupling on May 17, 1916, the design did not receive further development.

In the end, only 11 Felixstowe Porte Baby were built, of which the composite structure was used only once: on the previously mentioned flight on May 17, 1916. Production aircraft were used to patrol the North Sea, but its slow speed and large size made it vulnerable to fighter attack, ending the story of what was ultimately the first composite aircraft system.

And, I’ll be honest, I don’t know how these two planes were held together. I can only assume that John Port, rich in smart solutions, anticipated the design of the pyramid, which would later be used by Vladimir Sergeevich Vakhmistrov in his “Link” project to fasten the I-5 and TB-3 to each other. I have no other options, because the documentary film, entirely dedicated to this aircraft and filmed in 1917, is not available for viewing in any country outside the UK.

So, yes, the Short Mayo Composite was definitely not the first composite aircraft system, but its much greater contribution to history, due to the well-known fastening scheme and the ambitions of the creator, makes it more often remembered in the context of the annals of composite aircraft that it was the brainchild of Robert Mayo, and not John Porta.

Anyway, let's go back to the history of Robert Mayo's concept, and this time it makes sense to talk about the problems of such a design.

Problems

After gaining altitude and separating from the carrier, the mail plane had to cross the Atlantic and splash down in the waters of the destination port, unload, pick up the oncoming cargo of mail, wait for calm weather and fly back, heading for the native British islands, driven by favorable westerly winds.

At the same time, there would be enough fuel, but if a thunderstorm front appeared on the plane’s path over the middle of the Atlantic or, God forbid, a headwind, it was necessary to think about an emergency landing at sea. To reduce the risk on the return route, it will be necessary to consider the option of using the southern route, with intermediate refueling in the Azores and Portugal.

It was precisely because of the great risk of traveling in an easterly direction that the whole idea of Major Mayo's coupling was subject to fierce criticism from many aviation specialists, both in England and in other countries. Because, on the one hand, we have an original concept of a composite aircraft that takes off in a coupling and flies to its destination alone, and on the other hand, the obligatory possibility of returning home independently under its own power.

What is the point then, if it is commercially successful only in one direction, when the concept invented by Mayo works, while on the return route the problems of Short S. 33 return. For when the mail plane returns, it will deliberately be loaded with fuel so that the flight is successful at all , which means the payload that it can carry will also drop to the same level as the Short S. 33. And, which is typical, based on the results of all the developments, ideas and experiments, the payload should have been only 454 kilograms of mail!

Thus, from the point of view of the postal department, the introduction of the Mayo coupling into operation made some sense only from the point of view of maintaining the prestige of England as an aviation power, but there was no talk of commercial success.

However, the history of the composite aviation system is so full of adventurism that one doesn’t even want to think about it until, of course, we talk about analyzing the operation of such machines.

In any case, Short Brothers receives the previously mentioned Specification 13/33, the chief engineer of the entire company and the father of the Short Empire, Sir Arthur Goodge, is assigned to the project, and the long process of creating the first composite aircraft system in history is finally moving.

But the implementation of the concept, forgive the unexpected pun, was divided into two parts: designing the carrier and the mail plane. It had its own characteristics, which we’ll talk about now.

The potential customer for the composite aircraft, the British Post Office, insisted that both parts of the system be developed from scratch. If I correctly understood their line of thought, then they were overwhelmed by the desire to increase the speed of this design, and the implementation of this required detailed study and the creation of a new machine. Simply modifying the Short S. 23 Empire and, debatably, the Short S. 16 Scion could not get away with this: the task facing the company was too complex, ambitious and responsible.

It was also assumed that the transatlantic mail plane would have a speed higher or at least the same as the best land bombers and promising passenger aircraft created by that time in the United States and Europe. For example, the good bombers of the 1930s, the Martin B-10 and Avro Anson, had cruising speeds in the range of 250 to 300 km/h.

Well, I’ll keep the cruising speed of the resulting aircraft a secret for now.

And speaking about this customer requirement, I would like to point out that it was extremely ambiguous.

On the one hand, increasing the speed of new aircraft is a good thing, especially in the 1930s, when behind this there was also a desire to develop our own aviation as quickly as possible. The same Short company, which we will talk a lot about during the article, also dealt with bombers, as a result of which the creation of two completely new vehicles to the 13/33 specification could greatly help them in the future.

On the other hand, civil and postal transportation is not the best place for experiments, and using a simpler but proven solution in this industry was a good position. It’s not for nothing that they talk so much about the principle of “evolution, not revolution,” which, it seems to me, should have been adhered to in creating the model under discussion. At least the carrier could be created on the basis of the proven Short Empire, and that’s not so bad.

In any case, due to such requirements, the aircraft designers working on this project demonstrated some misunderstanding of the original concept: building a simple, cheap, sufficiently lifting and at the same time high-speed float-float seaplane was indeed a difficult task. Or rather, it is unreasonably difficult, because some requirements could well be abandoned in favor of implementing Mayo’s original, very correct idea.

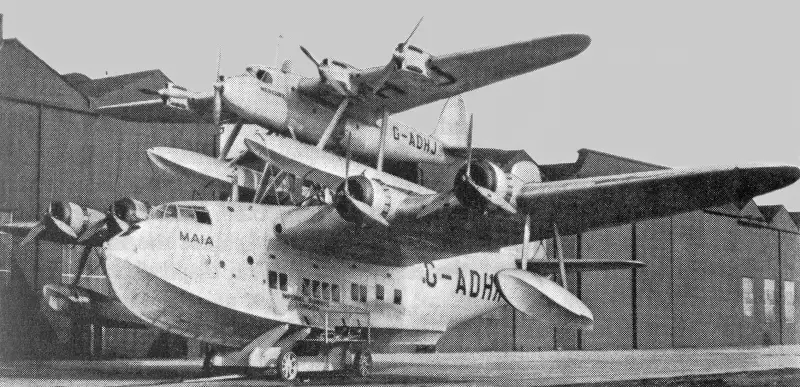

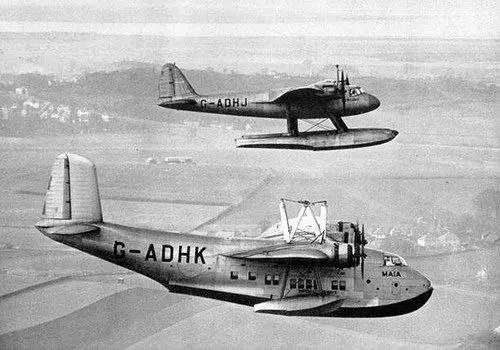

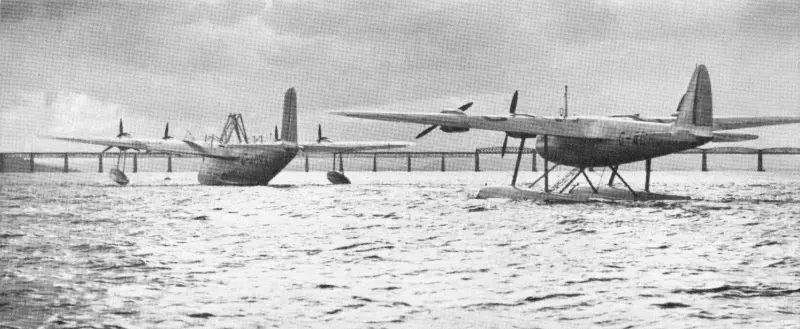

Be that as it may, the project began, and now it moved on to the design of the two components of the entire concept, which received their own names Short S. 21 Maia (G-ADHK) and Short S. 20 Mercury (G-ADHJ). The first was the carrier aircraft, and the second was the main part of the structure - the mail plane. And both of these parts were quite unusual, even though the medium was based on Short Empire. Both of them contained interesting technical features, the appearance of which was primarily determined by the operation of both machines in a composite state.

Let's briefly go over the design of each aircraft.

Design

Short S.21 Maia

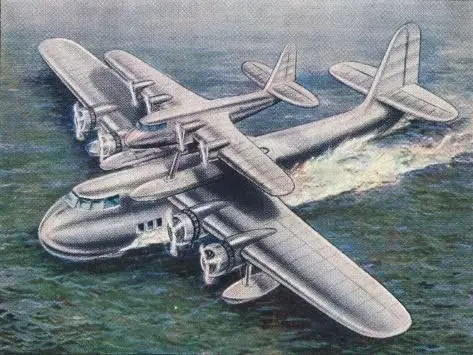

Although the Short S. 21 Maia was similar in general to the Short S. 23 Empire, it differed significantly in detail: the sides of the hull were widened to increase the planing surface (necessary for higher take-off weight) and had a "tumbling house" design (generally the term tumblehome came from shipbuilding and was created to describe a hull that becomes narrower than its beam above the waterline) rather than vertical as on the original car; large surface area of control systems; increasing the total wing area from 140 m² to 163 m²; the engines were mounted further back from the wing root to keep them clear of the Short S. 20 Mercury floats, and the rear fuselage was raised up to raise the tail relative to the wing.

The power plant of the car was as follows: 4 nine-cylinder Bristol Pegasus XC radial engines with a power of 919 hp. With. every. Like the Short Empire boats, the Short S. 20 Mercury carrier aircraft could be equipped to carry 18 passengers.

The Short S. 21 Maia's maiden flight, so far solo, took place on July 27, 1937, with Shorts chief test pilot John Lankester Parker at the controls.

Specifications:

Crew: 3

Capacity: 18 passengers

Length: 25,88 m

Wingspan: 34,75 m

Height: 9,95 m

Wing area: 163 m2

Empty weight: 11 kg

Maximum takeoff weight: 12,565 kg (Maia weight limit for combined launch)

Maximum takeoff weight: 17 237 kg

Powerplant: 4 × 9-cylinder Bristol Pegasus XC radial engines, 915 hp With. every

Maximum speed: 320 km / h

Range: 1 km

Practical ceiling: 6 100 m.

By the way, from another article in Flight magazine, or rather, a fragment from there, because I could not find it in its entirety, dated August 19, 1937, entitled “The Great Experiment,” we can learn that the creation of the Short S. 21 Maia was greatly delayed, due to the fact that the Short Brothers company was heavily loaded with the production of the Short Empire and unnamed military aircraft for the needs of the Royal Air Force. But although they are not named, I am inclined to conclude that we are talking about Short Singapore, the production of which ended exactly by June 1937.

As you can see, many of the features of the Short S. 21 Maia were designed in the name of increasing lifting power. Because Short has not yet been involved in the creation of a composite aviation system, and this suggests that they did not know about many of the nuances of operating such a design. In those places where it was possible to play it safe and improve the performance of the car without a lot of expense, this was done there.

But now let's move on to the main part of the whole concept: the Short S. 20 Mercury, created specifically for the 13/33 specification.

And this is not a figure of speech, unlike the carrier, the mail plane was completely original, but did not receive further development.

By the way, they played well with his name: in ancient Roman mythology, he is not only the patron god of trade, but also the son of the Pleiad sister Maya. As a result, quite interesting analogies arise: Short S. 20 is an airplane that establishes trade relations, and Short S. 21 is the goddess who created it.

Short S.20 Mercury

The Short S. 20 Mercury seaplane was an all-metal, two-float, four-engine (four 16-cylinder Napier Rapier VI piston engines with a power of 365 hp each) high-wing aircraft, created according to a normal aerodynamic configuration, with a crew of one pilot and navigator, who sat in tandem in a closed cabin. It could carry 450 kg of mail and 5 liters of fuel. Gas tanks occupied almost the entire volume of the wing, including the large box-shaped spar.

The flight controls, with the exception of the elevator and rudder trims, were locked in the neutral position until separation from the mothership. The maiden flight of the Short S. 20, also piloted by John Parker, who may be considered the little hero of this article, took place on September 5, 1937.

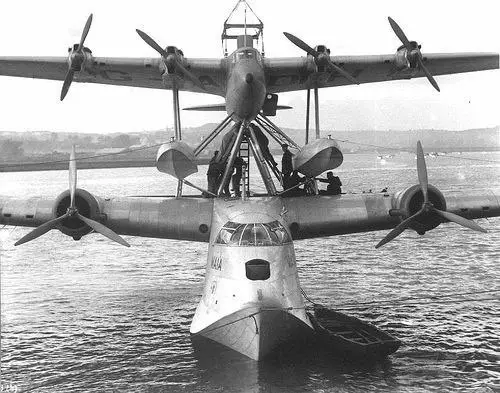

The mechanism holding the Mercury and Maia together was designed with lacy support trusses, securely connected by locks for the fuselage and floats that held the two aircraft together. In this case, a function was assumed, due to which a small movement was allowed even before uncoupling. Indicator lights indicated when the top component was in longitudinal balance so the trimmer could be adjusted before releasing. Pilots could then remove the corresponding locks. At this point, the two aircraft remained secured together only by a third lock, which automatically opened with a force of 13 N. The design was such that when separated, the Maia tended to fall and the Mercury to rise.

General characteristics:

Crew: 2 (pilot and navigator/radio operator)

Capacity: 454 kg mail

Length: 15,54 m

Wingspan: 22,25 m

Height: 6,17 m

Wing area: 56,8 m2

Empty weight: 4 kg

Maximum take-off weight: 7 kg (single take-off)

Twin weight:

9 kg (normal take-off weight)

12 kg (record starting weight)

Powerplant: 4 × Napier Rapier VI piston 16-cylinder engines, 365 hp. With. every

Performance:

Maximum speed: 341 km / h

Cruising speed: 314 km / h

Range: 6 km

*Extended range: 9 m

Wing load: 164 kg / m2.

And now everything is ready.

Flight

Two aircraft, which should become a single part of the communication between the Old and New Worlds, have been created, have been tested and are ready for use. But there is no hurry: a lot of money has been spent on the program, and if at least one of the planes is lost during a plane crash, the entire enterprise is closed.

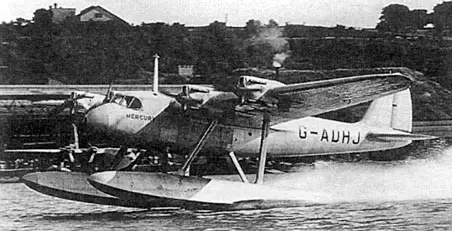

On January 20, 1938, the first flight of the Short composite aircraft system took place, but so far without disengagement in the air. However, this omission would be corrected on February 6, 1938, when the first successful mid-air separation was carried out in the skies over the Short company plant in Borstal, Rochestar, involving the Short S. 21 Maia and Short S. 20 Mercury aircraft. The first was flown by the permanent John Lancaster Parker, while the second was helmed by Harold “Pip” Lord Piper, a test pilot originally from New Zealand who came to Short in 1934.

After the first successful separation in air, a period of testing began, with the help of which it was necessary to confirm, refute or clarify the characteristics of the composite system. And so on July 21, 1938, the Short S. 21 Maia, piloted by Captain A. S. Wilcoxon, took off from the ground in the harbor of the Irish port of Foynes, at the mouth of the Chenon River, holding on its fuselage an aircraft that was destined to overcome the Atlantic Ocean.

Having reached the required altitude, they separate, and the Short S. 20 Mercury, which came completely under the control of Captain Donald Clifford Tindall Bennett, assisted by Midshipman A.T. Koster, heads to Montreal, and then New York. It is worth noting that in the cargo compartments of the Mercury, which appeared in his floats, there were about 270 kilograms of mail and the latest press.

The results

With your permission, I will quote from an article in Flight magazine dated July 28, 1938 entitled "Mercury Gives Good Results":

Mercury, the top of the Rapier-powered Short Mayo composite system, was launched at a normal gross weight of 20 pounds (800 kg), including 9 pounds of cargo, which included newsreels, press photographs, and so on.

Undocking from Maia took place on Thursday at 19:58, July 21.

After 13 hours and 29 minutes of flying over Cape Bald, Newfoundland, Mercury completed a record-breaking east-west crossing of the Atlantic. Boucherville, Montreal, was reached in 20 hours and 20 minutes.

The next stop was Manhasset Bay, Port Washington, Long Island, which was reached in 2 hours 11 minutes, making the entire flight take 22 hours 31 minutes, covering approximately 3 kilometers. Meteorological data indicates that they (the crew) encountered an average headwind of approximately 240 mph (25 km/h). Several long sections were covered in winds significantly exceeding this speed.

The flight was conducted primarily at altitudes ranging from 5 feet to 000 feet (11 to 000 meters)."

The remaining fragment interests us not so much, but if the story interests you, then below are the links where you can familiarize yourself with the primary sources (first and second).

The result of the first non-stop commercial transatlantic flight on a heavier-than-air aircraft was the following data: such a flight is possible, and Robert Mayo’s concept is working; the average speed of the Short S. 20 Mercury over the entire length of the journey was 284 km/h (or 177 mph from the original source).

To formulate another conclusion, let’s return to the article from Flight magazine:

This fuel efficiency coupled with the Mercury's high cruising speed gives some indication of the efficiency of the four 355/370 Napier Napier Mark VI engines, with range and speed well beyond original requirements. In fact, it (Short S. 20 Mercury) has proven that it can do significantly more than a 2-mile crossing of the Atlantic in a 000 mph headwind.”

The last judgment is, of course, ambitious, but after the successful flight, the euphoria of success probably overwhelmed not only the British written publications about aviation, but also the creators of the newly-minted newspaper hero, not to mention the investors and passengers who were lucky enough to be the first to cross the Atlantic.

The Short Mayo Composite continued to be used on various Imperial Airways routes, including numerous flights from Southampton to Alexandria, Egypt in December 1938, carrying a typically large volume of mail on Christmas Eve.

But one of the most important parts in the history of Mayo's composite aviation system happened in October of that year, and it is to this event that the epigraph at the beginning of the article is dedicated.

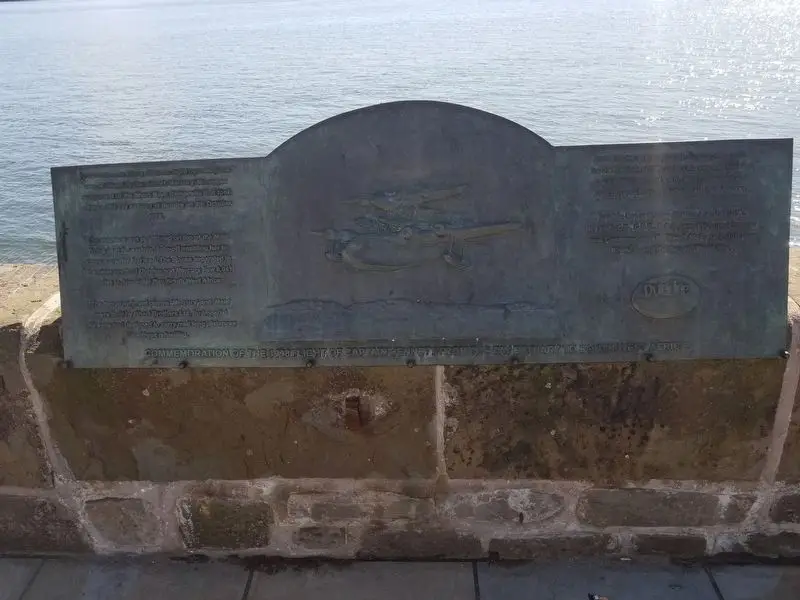

On October 6, 1938, the Short S. 20 Mercury, which had recently undergone a modernization aimed at increasing its flight range, set a new range record for non-stop flight for seaplanes: 9 kilometers. To achieve this, in its typical configuration on the Short S. 728 fuselage, the Maia Short S. 21 took off from Dundee in Scotland and landed at Orange River, Alexander Bay, South Africa. The entire flight took 20 hours, but, apparently, it was never registered by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, because the S. 41,5 took off not from the water, but from its carrier aircraft.

Such a long flight turned out to be not very tiring for the pilot, since the S. 20 was equipped with very advanced on-board equipment, in particular, the best autopilot at that time produced by Sperry Corporation. The S. 20's record-breaking flights across the Atlantic and to South Africa created excellent publicity for both Short Brothers and Imperial Airways, which once again demonstrated the absolute reliability of its aircraft.

And this flight took its place in history. On Tay Quay, near the RRS Discovery, a bronze plaque is attached to the causeway. It is dedicated precisely to this unregistered world record. It shows in relief two planes that are still connected, but have reached the altitude at which they must separate. There is also an inscription on the memorial plaque, a fragment of which I inserted at the beginning of my article, cutting it off in the final paragraph. Here's what it sounds like:

Short S. 26

Bleak End

True, the rest of the story is not so joyful.

It soon became clear that the success of Short Mayo Composite would quickly fade away. On July 21, 1939, the Short S. 26 G-class took off into the sky, which was supposed to take the place of the Short S. 20 in navy Imperial Airways. Its flight range was 5 kilometers, which was enough for a transatlantic flight without taking off from a carrier aircraft. The payload of the S. 100 reached 26 kilograms, and this also without the tricks of taking off from a carrier.

Aviation has simply stepped far forward, and the previously promising design found itself in the role of catching up, while having nothing that could be opposed to new aircraft in the industry.

Of course, the Short S. 26 was not a success: a total of three were produced, one of which was handed over to Imperial Airways to begin crew training in late September 1939, but just a few days after delivery the airline was informed that all three boats were together with their crews should be sent to military service (it is no coincidence, because just on September 1, 1939, the Second World War began).

Within the framework of the history of the Short Mayo Composite, what is important to us is the conclusion that it was inferior in many characteristics to a not very outstanding machine, which was never accepted for mass operation, and therefore, as well as with the characteristic problems of composite aircraft, the development of a refueling system in air in the UK, partly thanks to the company Flight Refueling Limited, and the outbreak of the Second World War, after which civil flights in general became very difficult, subsequent operation in the civilian sector was not possible.

But just as the S. 26 found itself in the ranks of the Royal Air Force at the outbreak of war, so the S. 20 and S. 21 were transferred to military service.

The S. 21 Maia was destroyed in Poole Harbor on 11 May 1941 after a German bomber raid, but the Mercury was reassigned to No. 320 Squadron RAF, which was based on personnel from the Royal Netherlands Naval Service. The aircraft in service with this squadron were often patrol planes and bombers, so I have two options: either the S. 20 was in the wings and used as a transport aircraft, or it was sent into the thick of things as a patrol aircraft .

Anyway, this squadron was based at RAF Pembroke Dock at the time. When this squadron was re-equipped with the Lockheed Hudson, the Mercury was returned to Shorts in Rochester on 9 August 1941 and was dismantled so its aluminum could be recycled for military use.

This is the end of the Short Mayo Composite story.

Heritage

The legacy that this aircraft left is perhaps invaluable.

The concept implemented by Robert Mayo, created in a certain context of time and for specific tasks, was unsuitable for the mass transportation of passengers and mail, as evidenced, among other things, by the resounding failure of the Empire Air Mail Program. At the very least, the Short Mayo Composite was an unsuccessful example of a composite aircraft system as intended by the chief designer, but this does not change the fact that this idea continued to live after the completion of the Short Mayo Composite.

FICON program to create the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin parasite fighter in conjunction with the Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber; Boeing 747SCA, designed to carry Space Shuttle orbiters; the Lockheed D-21 reconnaissance drone, which was originally part of the Lockheed M-21, but soon went under the wing of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress; many other real and only sketch projects, which include such iconic ones as the Bartini A-57, and, of course, everyone’s favorite An-225 Mriya. A machine that has earned its cult status, having not made many flights with the Buran on its back, but was originally developed as a carrier of oversized cargo, with an eye to using a composite system design.

It would be bad manners or even some careless simplification to say that Short Mayo Composite appeared in the wrong place at the wrong time. It seems to me that this machine was created in its time, by the people who were supposed to work on it, but the concept itself is ineffective when it comes to creating something systematic: bombers or passenger planes.

It exhibits brilliant qualities during less than ordinary use, such as use as a shuttle carrier. And one of the implemented concepts, in which all the best aspects of composite aircraft systems could be demonstrated, was tested in Germany at the end of World War II.

In the next article, I hope we will be able to find out the history of the “Beethoven device”...

Information