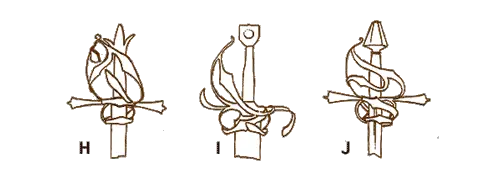

Museum affairs. Three different schiavones at once

Venetian Schiavone swords 1480–1490. and shestopers of the XNUMXth century. Venice and Hungary. They had a horizontal crosshair curved in the shape of the letter S. Traditional weapon Doge's Guard. Arsenal of the Doge's Palace in Venice. Author's photo

endure difficulties

do your job -

proclaim the Good News,

do your service.

Apostle Paul's 2nd Epistle to Timothy

Culture and story. It would seem, what relation do these words from the epigraph have to the topic of Venetian schiavona and museum affairs? But if you think about it, it's the most direct. There are more than enough difficulties in the work of museum workers, as in any other good job. True, they are of a somewhat specific kind.

Well, for example, a man came to you and brought you a handle from a French sapper cleaver to your department. Appearance – “so-so”. There is no blade. The French did not enter your region in 1812. And what should we do with “this”? Take it for storage, give it to a restorer, or throw it away, and that’s the end of it.

Cleaver handle. Photo by the author

Here's another interesting artifact.

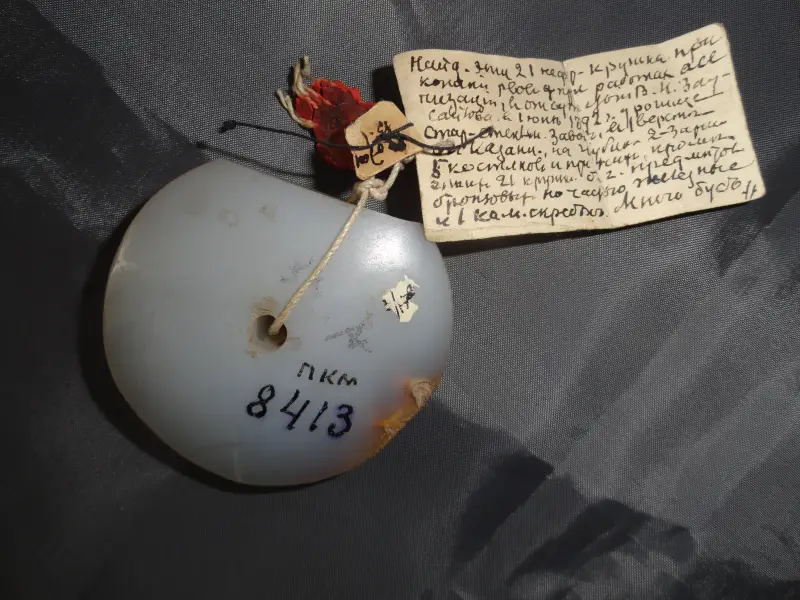

Onyx disc. Found back in 1892, some miles from Kazan at a depth of 2-3 arshins among five skeletons. Many beads, bronze rings and mugs, iron objects and a stone scraper were also found there. All this was written on the accompanying piece of paper, apparently, even before 1917. And... then this disk was placed... in the reconstruction of a Mordovian burial (!), on the skeleton’s chest as a decoration.

Meanwhile, this is nothing more than the pommel of the hilt of a Sarmatian sword, evidence of which is analogues of such disks found in Bulgaria. That is, it could well have been a chest decoration. That is, people dug up a Sarmatian burial, saw it, liked it, and put it on themselves. It’s just that it wasn’t indicated anywhere...

The pommel of a Sarmatian sword. Penza Regional Museum of Local Lore. Author's photo

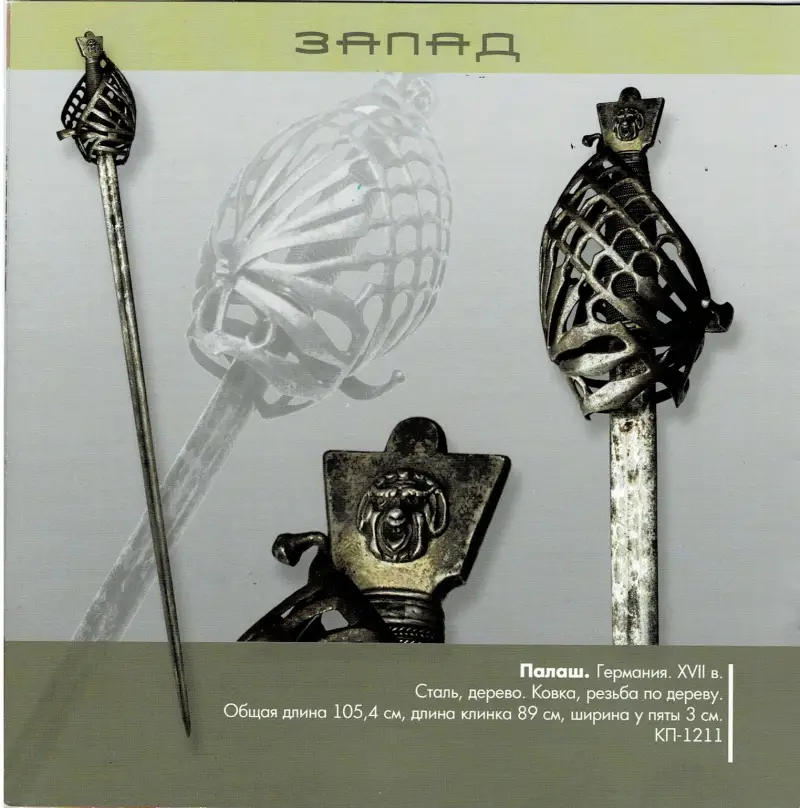

And here is a page from the catalog of the 2016 exhibition “West - East. The shine of the blade and the sound of cold steel”, held at the Samara Regional Museum of History and Local Lore named after. P. V. Alabina. And on it you see a typical schiavona, which was simply called a broadsword. Which, in principle, is correct, but could be clarified. The weapon is very interesting. Yes, but is its weight indicated? No, although it is interesting. It is not listed because our regional museums simply do not have large scales. They are not entitled to them... What a pity!

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, their schiavona is also not named after them. There it is called broadsword, which translated into Russian means “broadsword”. But all the necessary measurements are present in the description. Time: XVIII century Cultural affiliation: Italy, Venice. Materials: steel, brass, wood, leather. Total length 98,4 cm. Blade length 83,8 cm. Weight: 1 g.

By the way, the American Schiavona looks exactly like the example from Samara. So, maybe the dating in it should be changed from the 17th century to the 18th?

But I would still like to know more about this weapon.

It turned out that this topic was dealt with not only by such a master of weapons science as Evart Oakeshott, but also by Nathan Robinson, a professional web developer from San Francisco, who even founded his own resource dedicated to edged weapons, and in particular the same Schiavone.

So let's see what we can learn from their materials published at different times.

First of all, it is noted that schiavons are found with both single-edged and double-edged blades of different lengths with and without a fuller. In modern Italian, the word schiavo means "slave" and slavo means "Slav". In Venetian Italian, contemporary to the sword itself, this word referred to... a “Slavic woman,” and perhaps a Dalmatian. This translation is interesting because it suggests: the name of the weapon corresponds to the habit of calling the sword “she”.

But the generally accepted definition of schiavona, quoted in many texts and specifically meaning “mercenary soldier,” is most likely incorrect. Although, despite the confusion with the name itself, the schiavona can certainly be associated with soldiers recruited from the territories that were under the influence of Venice in the Balkans. Moreover, it was from them, as foreigners who had no roots in Venice, that the bodyguards of the Venetian Doge were recruited.

Early swords of this type were characterized by a “cat’s head” pommel, called katzenkopfknauf in German, and an S-shaped crosshair, which can be found on surviving examples of swords with a hilt of the 14th century. These types of swords are now often called schiavonesca, but it is probably more accurate to call them "spada schiavona" (meaning "Slavic sword").

The question of the name schiavona for swords with basket hilts becomes even more complicated - after all, did they come from somewhere?

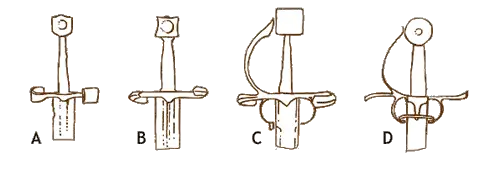

Let's look at the first picture, and there are the first two swords (A and B). They demonstrate the ancient Hungarian cross-hilt style, which developed in the late Middle Ages. Then came the C-arm - with the addition of finger rings. Example D - how this type of handle developed and became more refined

A continuing development is the E sword hilt, which incorporates the distinctive Spanish incised design. The F sword is similar, it is not slotted but has a unique pommel. The G sword represented an unusual variant of the typical Hungarian-Venetian square pommel

Looking again at the trident pommel of the F sword, we can see not only some similarities and connections between this early style and the newer schiavona.

The hilt of the H sword has a characteristic trident-shaped pommel, like the F sword, but is combined with a typical South German hilt and already has a basket guard, more reminiscent of a schiavone guard. By the way, the last three handles (H, I and J) are extremely important in order to draw any conclusion about the origin of the fully developed schiavona

Type 1 and type 2

Ewart Oakeshott divided schiavona into two main categories, which he called type 1 and type 2. Type 2, in turn, has two variants of increasing difficulty called 2a and 2b. As shown in the figure, Type 1 is not only visually simpler than the others, but also differs from it, so that it could be classified as a completely different handle shape if not for the general manufacturing methodology and the characteristic “cat’s head” pommel. This might suggest that these hilts were issued by the regiment, but this cannot be confirmed.

The guards on Type 1 handles are flattened, wide and always have a simple leaf-shaped shape. The rear cross has a square cross-section, flares out at the end, and usually curves outward. At the bottom of the basket, covering the ricasso area of the blade, there are two pointed rods, intersecting and attached at the ends. Type 1 hilts appear to have originally always had a "cat's head" pommel, although its shape and material may have varied.

Type 2 guards are more complex. The upper loop of the handle, in contrast to the three flattened shapes seen in Type 1, is formed by a pair of diagonal narrow strips connected to each other by a series of short strips located at right angles to the loops. Pommels were made of iron, bronze or brass, and even solid silver.

Type 2a and Type 2b

The type 2b design is the most complex due to the addition of another row of security loops creating three rows of cutouts. Of all four types, Type 2 hilts have the greatest variety of designs and decorations. It is unknown which type of handle arose first or whether one evolved from the other. This issue is complex, so after all of the above it is reasonable to conclude that different types of hilts were modern and it is quite possible that the schiavone guards developed differently in different regions.

By the way, in Venice itself, a variety of swords were in use, and not just schiavones, which clearly remained a weapon of heavy cavalry. Arsenal of the Doge's Palace in Venice, photo by the author

In any case, according to Nathan Robinson, the main thing about Schiavone is that she... was. It was in the 17th–18th centuries. and was used on the territory of Italy and the German principalities, and is somehow connected with the Slavic peoples of the Adriatic region.

Now let's return to our Penza schiavone with a handle that has, unfortunately, been replaced. As you can see, it belongs to type 2. It is interesting that on its blade, in addition to the image of the Passau wolf, there are several other marks. Author's photo

"Cross and Circle"

"Head of the King"

Well, the famous “running wolf” is right there...

PS

By the way, the schiavona from the Samara museum clearly belongs to their most complex and late type and cannot possibly date back to the 17th century.

Information