Armor-piercing tips of naval shells 1893–1911

After talking about testing methods for domestic projectiles, let's move on to armor-piercing tips.

It is quite obvious that the armor-piercing qualities of projectiles are increased as a result of strengthening its body through the use of high-grade steel and special heat treatment. However, in the 19th century it became clear that there was another way to increase the effectiveness of overcoming armor.

The appearance of armor-piercing tips in the Russian Imperial Navy

In Russia, the idea of an armor-piercing tip was conceived and proposed by Admiral Stepan Osipovich Makarov in the early 1890s. One can argue whether he was the discoverer, or whether such a tip was invented earlier somewhere else, but for the purposes of this article this is completely unimportant. But it is very important to understand that in those years the physics of the process of overcoming armor with a projectile was still completely unstudied. That is, it was clear that the tip made it possible to enhance the armor-piercing effect of the projectile, but no one understood why.

In Russia, at first they tried to explain the increase in armor penetration by the fact that the tip seemed to soften the stress upon impact, which helps maintain the integrity of the head of the projectile. Accordingly, the first experiments were carried out with armor-piercing tips made of soft metal. However, our gunsmiths, who considered the armor-piercing projectile to be the main weapons ships, did not stop there and experimented a lot with tips of different shapes, made of different metals. It turned out that hard steel tips provide projectiles with better armor penetration than “soft metal” ones.

The theory behind this fact was the following: the task of the tip is to destroy the cemented layer of armor, in which case it itself will collapse. But in this way the tip will pave the way for the projectile, moreover, its fragments will compress the head of the projectile, protecting it from destruction in the first moments of impact on the armor. Our gunsmiths came to this hypothesis based on the results of experimental firing, during which it was revealed that the armor-piercing tip of hard steel was almost always destroyed upon impact, and its fragments were usually found in front of the plate, and not behind it. In addition, this hypothesis well explained the fact that the armor-piercing tip was useful only for overcoming surface-hardened armor, and had no effect when firing at uncemented armor plates.

As I already wrote earlier, among domestic 12-inch shells, for the first time an armor-piercing tip appeared on 305-mm ammunition mod. 1900, but in fact such shells did not even make it in time for the Battle of Tsushima. Only part of the 152-mm shells of the ships of Z.P. Rozhdestvensky’s squadron had armor-piercing tips. And, unfortunately, the sources available to me do not answer the question of whether the first serial armor-piercing tips were “soft metal”, or whether hard steel tips immediately went into production.

Professor E.A. Berkalov in his work “Design of Naval Artillery Shells” indicates that in Russia they switched to tips made of durable steel, similar in quality to that from which the shells themselves were made very quickly and earlier than other powers . Alas, this is all I have at the moment.

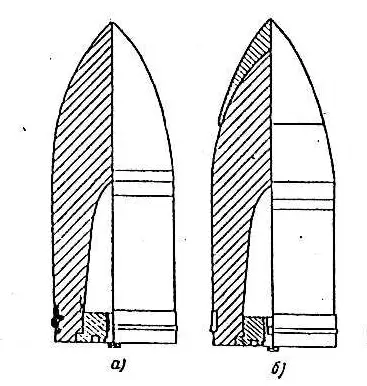

As for the shape of the armor-piercing tip, it is in the Russian Imperial navy was adopted as pointed, that is, looking at the silhouette of the projectile from the side, an inexperienced person may not even understand that the projectile has a tip.

In this form, armor-piercing tips existed in the Russian Imperial Navy until the advent of projectiles mod. 1911, which we will return to a little later.

Armor-piercing tips in the US and foreign navies

Very interesting are the arguments of Mr. Cleland Davis, published in the United States Naval Institute magazine for 1897, regarding the state of affairs with armor-piercing caps in the USA. I will give the main postulates below.

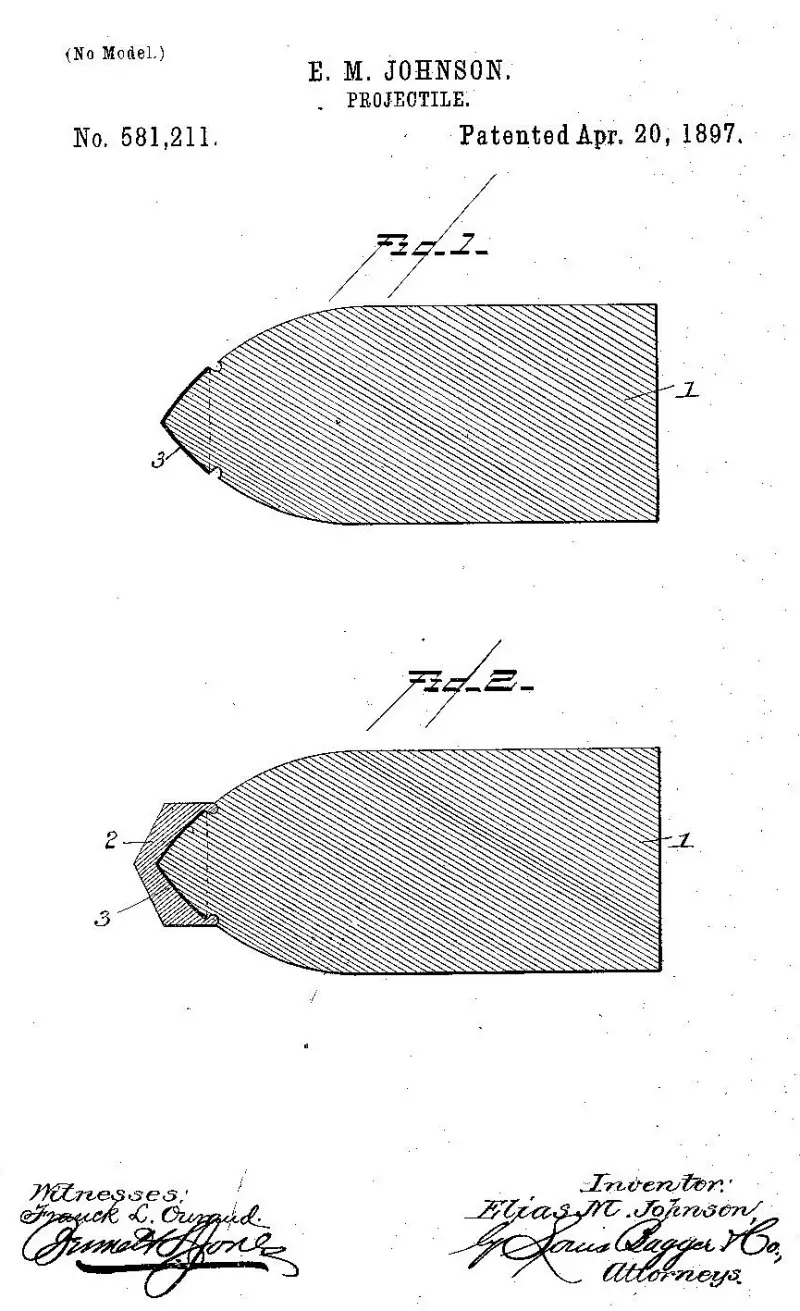

The US Artillery Department experimented a lot with various types of armor-piercing caps (as in the translation of the article given by Naval Collection No. 1 for 1898), until it settled on one of the options, which was extended to all available shells. This cap was a cylindrical piece of mild steel, with a diameter of half the caliber of the projectile. In the lower part of the armor-piercing cap, a recess was made in the shape of the top of the projectile to a depth of 2/3 of its length - in fact, with this recess the cap was put on the projectile. In this case, a shallow recess of 0,03 inches (about 0,76 mm) was made on the inner surface of the cap adjacent to the projectile, which contained a lubricant.

Cleland Davis describes the tip as cylindrical, but in the picture we see a slightly different shape. However, if you look at photographs of American shells, the shape of the tip is really close to a cylinder and certainly does not look pointed.

It is interesting that, according to Cleland Davis, in the USA no one really understood how this tip works. According to the patent obtained by Mr. Johnson, the effect of the cap was that, covering the top of the projectile, it strengthens the projectile by increasing the resistance to its lateral deflection and longitudinal compression. Others thought that the whole point was that the armor-piercing cap acts as a kind of buffer between the projectile and the armor, weakening the impact upon impact on the projectile body - that is, the same version was in circulation as in Russia in relation to mild steel tips.

However, Cleland Davis considered both versions as not entirely reliable and was inclined to explain the effect of armor-piercing hard steel tips in Russia. Its essence was that such a tip makes a “hollow in the slab,” that is, it damages the cemented layer, thereby facilitating the passage of an armor-piercing projectile through the slab. At the same time, Cleland Davis believed that lubrication could play a significant role in helping the movement of the projectile in the armor.

In general, Cleland Davis gave the following conclusions based on the results of firing tests of armor-piercing tips:

1. A projectile equipped with a solid cap of the final shape, but without lubrication, turned out to be better than a projectile without a cap.

2. A tip in the form of a simple cylinder with thick walls has the same effect as a solid cap if both are used without lubrication.

3. A thin-walled cap with lubricant does not have any effect.

4. The best result is a thick-walled or solid tip made of mild steel with lubricant.

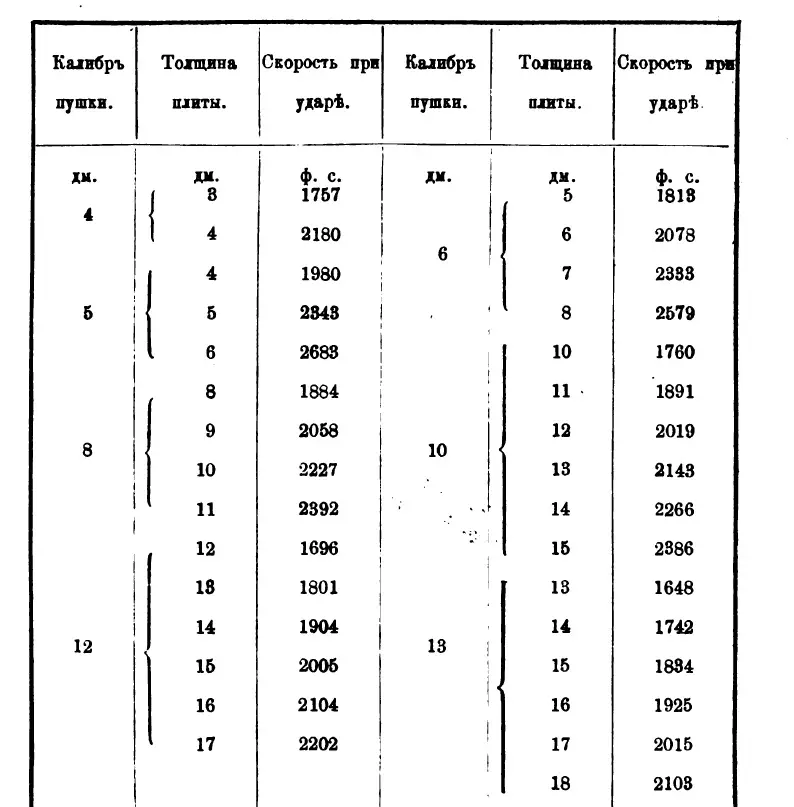

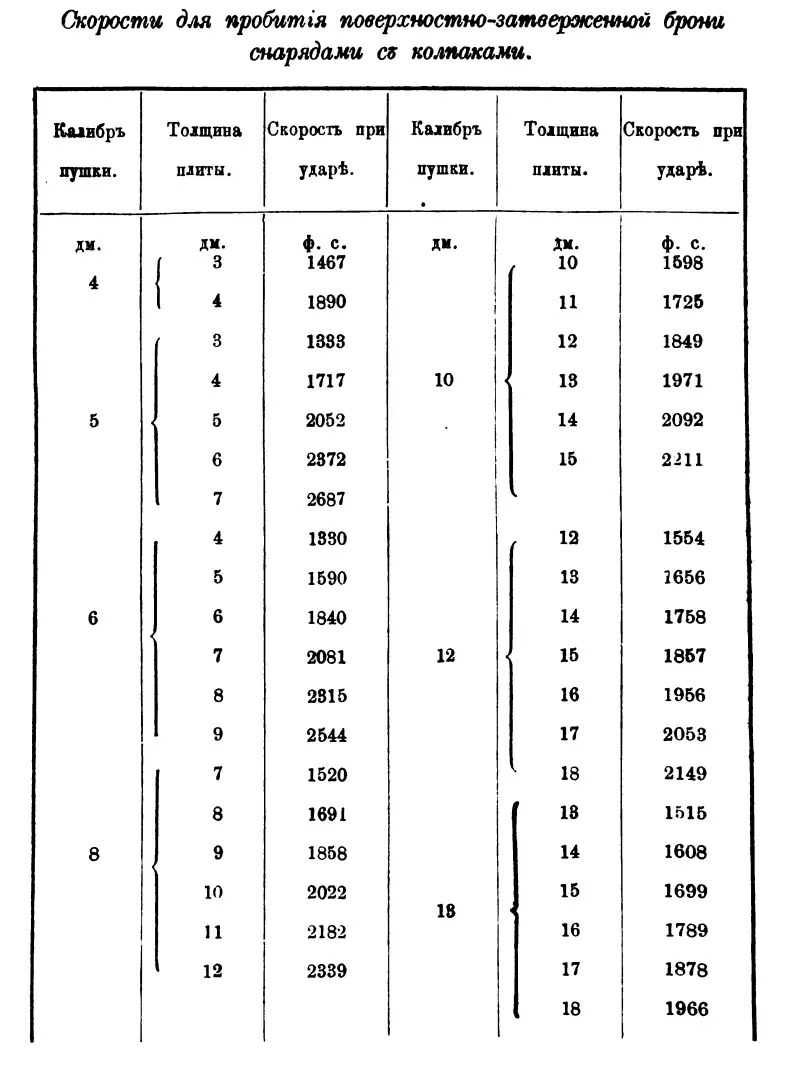

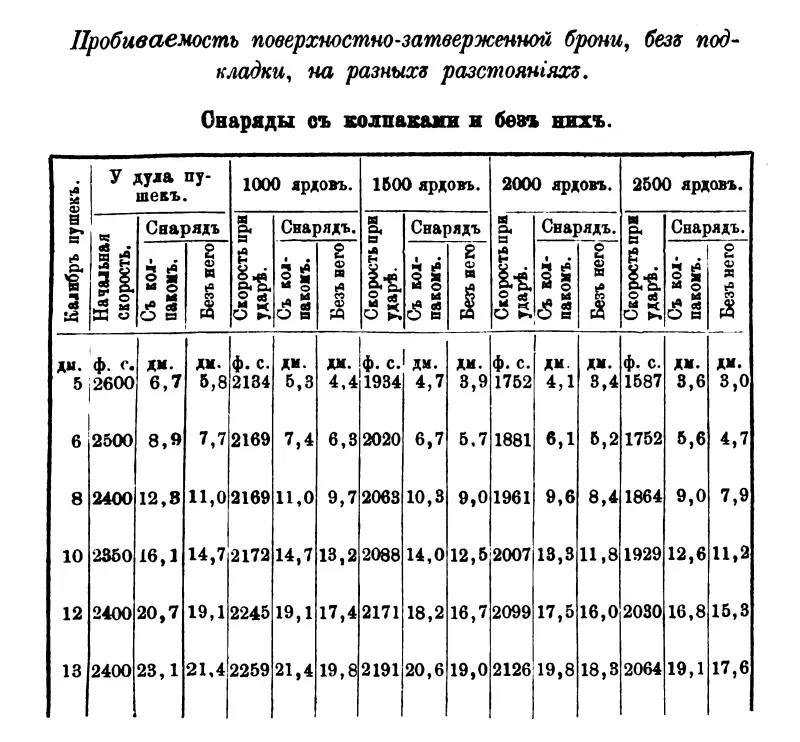

In general, the effect of the armor penetration of American armor-piercing caps is perfectly described by the following tables. The first of them demonstrates the speeds at which, according to the standards of the American Navy, shells of the specified caliber penetrate armor of one thickness or another. The second is the same thing, but with a cap, and the third is the comparative armor penetration of projectiles equipped and not equipped with armor-piercing caps, for different distances.

From the tables we see that, for example, when firing a 12-inch projectile at a 305 mm thick plate, the American soft metal tip made it possible to reduce the speed of the projectile on the armor by 8,37%.

Were our armor-piercing tips better than the American ones presented by IG Johnson?

Professor E.A. Berkalov points out that “in our shells, the projectiles are mod. 1911, as well as in most foreign shells, a pointed tip was used... In the German experimental shells by Krupp and the English by Hatfield, a cylindrical tip was used, which, according to information, gave an advantage over the pointed tip, apparently due to the larger area of work of the tip in moment of impact. But a projectile with such a tip receives a shape that is not satisfactory in ballistic terms and in actual conditions, due to the greater loss of speed by the projectile during flight, it may turn out to be worse than a pointed one.”

However, it is necessary to take into account that in the domestic fleet, test firing was carried out exclusively at normal range. At the same time, “experiments in shooting at armor at angles showed the undoubted advantage of flat-cut tips, both foreign and our shells switched to such tips” (E. A. Berkalov).

Armor-piercing tips arr. 1911

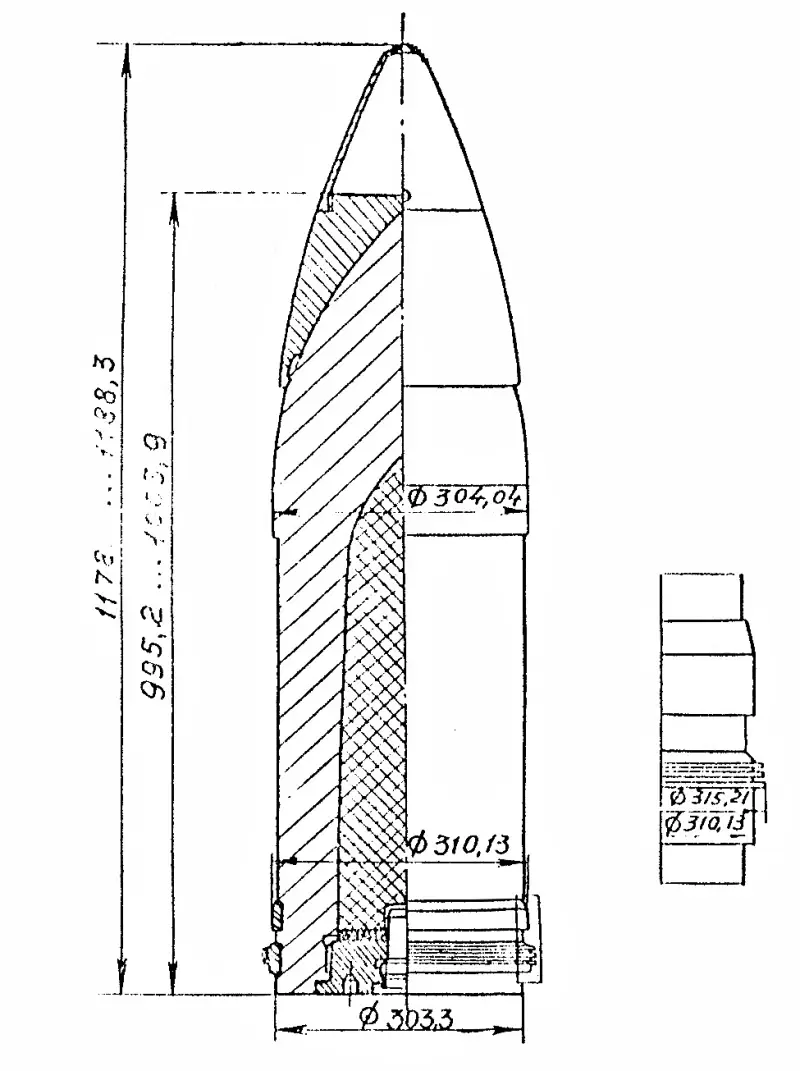

Having realized the advantages of flat-cut tips, domestic artillery specialists began to look for a method that would neutralize their disadvantages. The answer was found quickly enough - in the form of a ballistic tip. Simply put, armor-piercing 305-mm shells mod. 1911 were equipped with two tips - an armor-piercing flat-cut one, attached to the head of the projectile, and a ballistic tip, which was attached to the armor-piercing one and ensured the preservation of favorable ballistic qualities.

However, the first ballistic tips made of steel, showing excellent results when shooting at armor plates in the normal direction, did not allow them to penetrate armor at an angle of 25 degrees deviation from the normal. That is, it turned out that a projectile with a new armor-piercing tip, but without a ballistic tip, penetrated armor properly, while maintaining the integrity of the body, but with a steel ballistic tip did not penetrate the same armor plate at all.

Such a discouraging result required additional research, during which they came to the use of extremely thin (1/8 inch or 3,17 mm) brass tips, which were used in projectiles mod. 1911. It was obvious that such a delicate structure could easily be damaged when overloading or repositioning shells. A solution was found in a simple fastening of the ballistic tip - it was simply screwed onto the armor-piercing one, and 10% of spare ballistic tips were sent to ships to replace damaged ones.

In general, the design of the tips for the 305-mm armor-piercing projectile mod. 1911 looked like this. The armor-piercing tip had the shape of a truncated cone with a height of 244 mm, the larger base of which had a diameter of about 305 mm, and the smaller one (the front cut, which, in fact, the tip hit the armor) - about 177 mm. This cone, on the side of the larger base, had a recess in the shape of the head of the projectile, which was attached to the projectile, while the very tip of the projectile almost reached the smaller base.

Along the edge of the smaller base of the cone there was a small recess with a thread into which a hollow brass ballistic tip with a height of 203,7 mm was screwed. The height of the void in the ballistic tip was thus 184,15 mm (7,25 in). The method of attaching the armor-piercing tip to the projectile was the same as the ballistic one - using a conical screw thread.

E. A. Berkalov especially notes that in increasing the area of the front cut of the flat-cut tip, we went further than all known designs, which gave our armor-piercing tip a significant advantage over all the tips that existed at that time in the world.

At the same time, the professor specifically stipulates that it is possible to increase the area of the front cut only to a certain limit, beyond which the need to thicken the walls of the ballistic tip, “put on” over the armor-piercing one, will negate the increase in armor penetration, as happened with the first versions of the steel tips described above.

Of course, the use of a thin brass ballistic tip also made it possible to increase the armor penetration of domestic projectiles, since the flat-cut tip no longer deteriorated the ballistic qualities of the projectile.

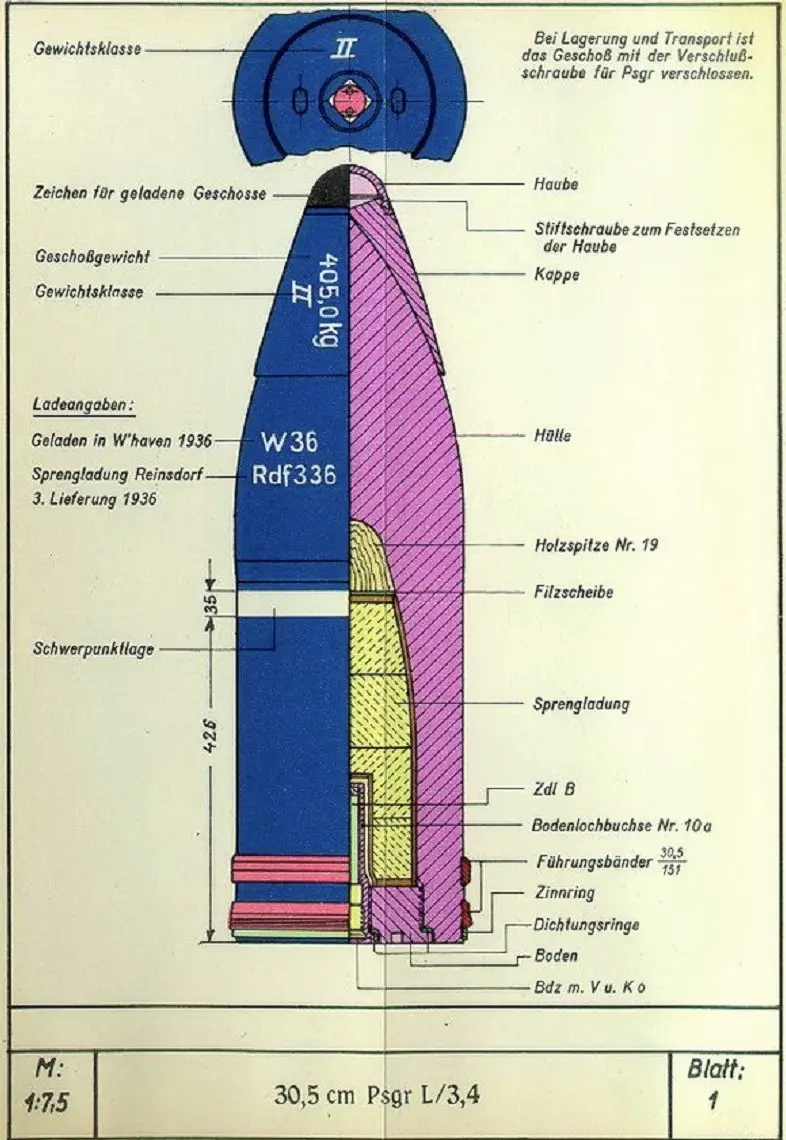

Similar tips appeared in other naval powers, but, as E. A. Berkalov points out, “foreign armor-piercing shells have an armor-piercing tip with a significantly smaller cutting area.” Still, it should be assumed that foreigners in this matter caught up to our level quite quickly, as is hinted at by the drawings of the German 305-mm projectile from the First World War era: however, the study of this issue is beyond the scope of this article.

It is noteworthy that the German tip has a significant difference - instead of a flat-cut shape, we see a cone-shaped recess. E. A. Berkalov found it difficult to characterize its usefulness, which could only be confirmed by conducting numerous experiments comparing this form of tips with ours.

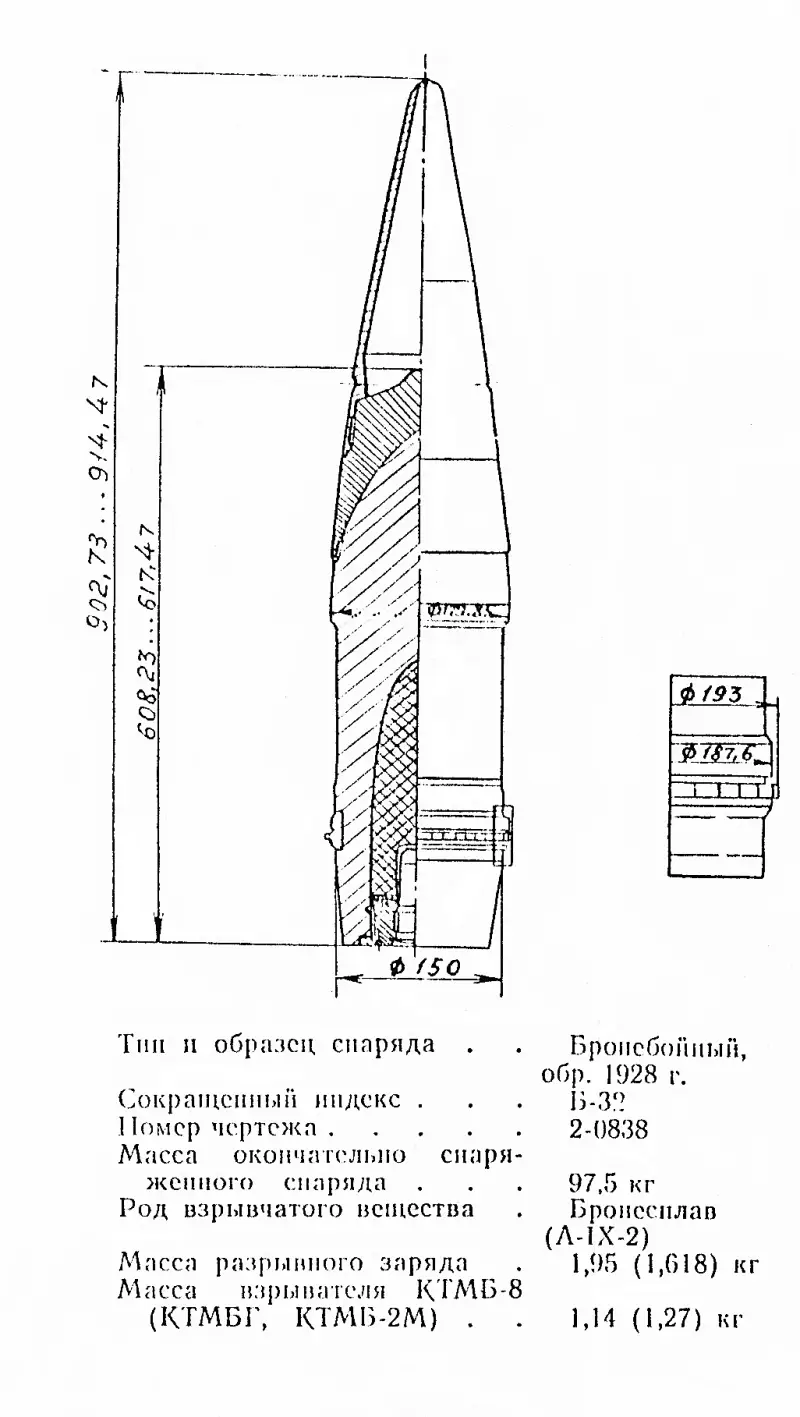

One can, however, assume that the optimal shape was neither one nor the other, but rather intermediate between the pointed Makarov tip and the flat-cut tip. In the “Album of Naval Artillery Shells” from 1979, we see such tips on armor-piercing projectiles mod. 1911 and 180-mm caliber shells, while in the 1934 album these same shells are equipped with conventional “flat-cut” tips.

It must be said that E. A. Berkalov, noting the obvious advantage of the combination of armor-piercing flat-cut and ballistic brass tips on projectiles mod. 1911, compared to other domestic and foreign products for a similar purpose, I was still not sure about the optimality of the “flat cut”. Therefore, it can be assumed that further research led to the determination of a more advanced form of armor-piercing tip. However, such an evolution of the tip occurred much later than the period we are studying, and is not related to the topic of this cycle.

The second significant difference between foreign armor-piercing tips and domestic ones was the method of attachment to the projectile. Ours were screwed on using a screw thread. Foreign ones were attached by pressing the tip into special recesses or into a circular ledge made in the head of the projectile.

E. A. Berkalov believes that the foreign method is better than the domestic one, but under one condition. Namely, if abroad it was possible to achieve a tight fit of the tip, because although when moving in the barrel bore and in flight, “our projectiles are protected from screwing together the tips, still when handling the projectiles one can assume the possibility of at least partial unscrewing, and therefore violation tightness and strength of fastening.”

The effectiveness of the armor-piercing tip of projectiles mod. 1911

Obviously, the effectiveness of an armor-piercing tip is determined by the reduction in the speed of the projectile on the armor to penetrate it, in comparison with the same projectile not equipped with a tip. Numerous domestic experiments have revealed that armor-piercing tips arr. 1911... they love everything big. That is, the greater the caliber of the projectile and the armor plate being penetrated, the higher the effectiveness of such a tip. E. A. Berkalov gives a reduction in speed for projectiles with tips of different calibers when firing at a 305 mm plate:

1. For a 203 mm projectile – 7,25%.

2. For a 254 mm projectile – 11,75%.

3. For a 305 mm projectile – 13,25%.

Unfortunately, E. A. Berkalov does not provide similar data on the armor penetration of the “Makarov” tip. In the future, after analyzing the results of firing domestic projectiles with tips of this type, I will try to find the answer to this question myself.

It is not possible to evaluate the effectiveness of American (IG Johnson) and domestic (pointed “Makarovsky”) tips when a projectile hits the plate at an angle other than 90 degrees.

On the one hand, with the same projectile speed on the armor, a flat-cut tip shows a noticeably better result than a pointed one.

But on the other hand, due to worse ballistics, a projectile with a flat-cut tip will not produce the same projectile velocity on armor as a projectile with a pointed tip fired from the same gun.

To be continued ...

Information