"Phalanx" opens the battle account. 45 years after its appearance

Yes, it happens: developed in the 60s of the last century, put into serial production in 1978 and put into service in 1980, the Mark 15 Phalanx CIWS anti-aircraft artillery system or simply “Phalanx” recently won its first official victory.

It would seem, what is wrong with this event? Well, a gun. Well, with radar. Well, she shot down an anti-ship missile on approach to the ship. Everything is as it should be, isn't it? In fact, everything is much deeper than it seems at first glance.

The fighting that unfolded between the Yemeni (also called the Houthis) and the American military in the Red Sea proves that the Phalanx close-in combat system works, and works quite effectively. However, then the second question arises: how effective are the long-range defense systems on American ships, now that the last line of defense system is in use?

However, it is in order.

In general, it is worth noting that the development of shipborne air defense systems has proceeded quite smoothly since its inception.

During the First World War, these were ordinary machine guns and guns that were installed on ships and taught to shoot at the upper sector.

The sighting devices left much to be desired, but given that the targets were airplanes and airships whose speed did not exceed 200 km/h, Maxim’s machine guns, together with Lander’s cannons, more or less coped with their tasks.

During World War II, a typical US Navy warship might have a dozen or more 40mm Bofors guns and even more 20mm Oerlikons.

The Giering-class destroyer, which formed the basis fleet wartime destroyers, was equipped with six 127 mm guns, 12 40 mm Bofors automatic guns and 11 20 mm Oerlikons.

The task of the calculations was as simple as possible: to shoot a large amount of ammunition into the sky in order to create an insurmountable space for aircraft from stern to bow.

It turned out, let's say, differently. The anti-aircraft gunners of the destroyer Aaron Ward (third) succeeded, but somehow the crews of the battleship Yamato did not succeed.

Radar and automation changed all that. With radar, a single artillery system with a computer brain can detect multiple targets, calculate their distance, speed and direction, and precisely destroy threats in order of priority. This promised to free up tons of space on warships, with one such weapon performed the work of more than 20 World War II guns.

Of course, there were certain changes. Anti-aircraft installations, both missile and artillery, and missile and artillery began to be installed not on the sides and on the bridges, but along the axis of the ship, in order to ensure the largest possible sector of fire.

Here's a video of the Phalanx on the amphibious assault ship USS Germantown using a Marine Harrier jet as a targeting target.

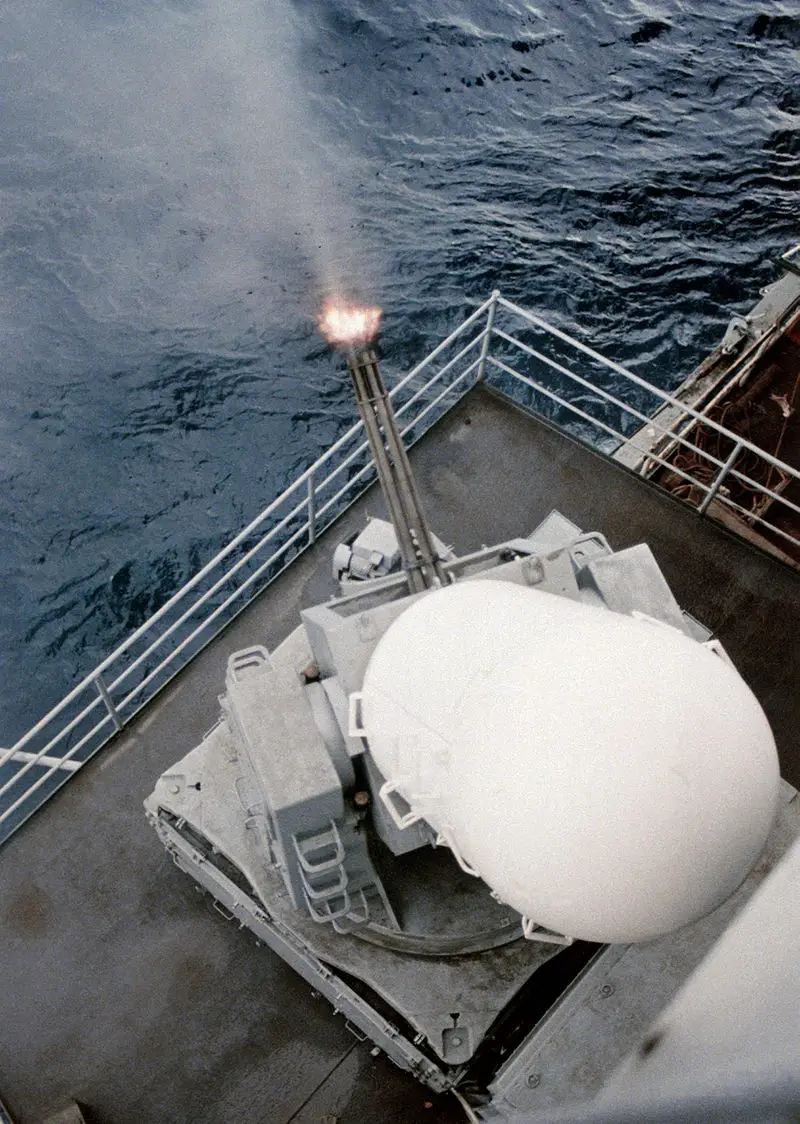

What can be said about a system about which everything or almost everything has been said? The Mk-15 Phalanx is an M61A1 Gatling system, the same six-barrel cannon found on the F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon fighters, mated to a Ku-band radar and computerized fire control system. Naturally, the Phalanx has changed its electronic components more than once over almost half a century, this is understandable. And remote control was improved.

The system works like this: after the weapon is activated from the ship's combat information center, it automatically begins scanning the sky for incoming airborne threats. The system is fully automated: the need to combine radar and ballistic data and accurately fire on the target just a few seconds before impact with the ship eliminates human intervention. Only a computer can react fast enough.

As the Phalanx's radar begins to detect incoming missiles, it prioritizes the first six missiles at a range of 5,58 miles. The Phalanx automatically engages incoming threats at a range of 9 km, sending a hail of 20mm shells towards the incoming missile. The M61A1 has a rate of fire of 4500 rounds per minute and can carry 1500 rounds of ammunition with a tungsten or depleted uranium core. The ammunition is enough for 20 seconds of shooting. According to calculations, the “Phalanx” should fire for about 1-2 seconds per battle.

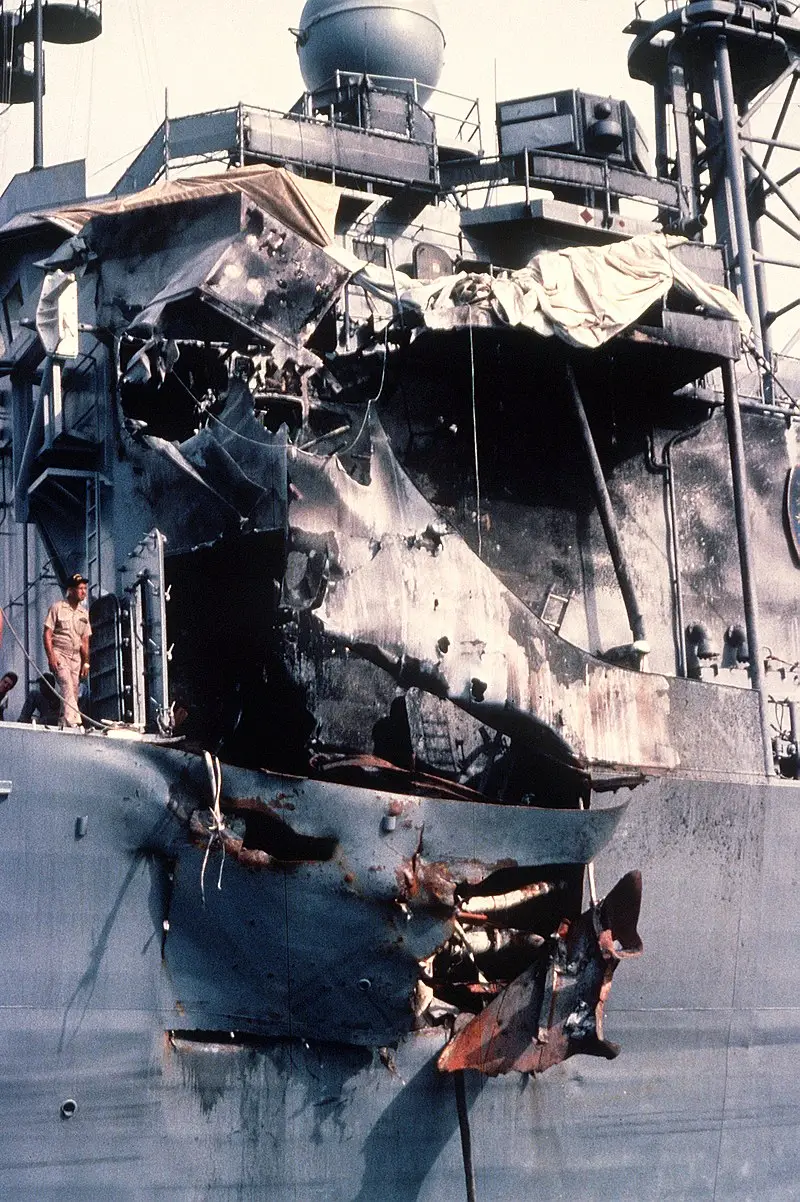

There are, of course, such cases as with the frigate Stark.

Why, you ask, if the Phalanx is such a gorgeous weapon? And it’s simple: on May 17, 1987, the crew of the frigate saw the Iraqi Mirage, they assumed that the plane posed a threat, and a combat alert was sounded on the ship. But the anti-aircraft missile control post of the frigate Stark reported that the Mk 92 fire control station of the Phalanx complex could not detect the target, since the ship’s superstructures “shaded” the bow heading angles from which the aircraft was approaching. According to Navy instructions, in such cases the ship should turn away from its course at an angle of up to 90°, but the Stark continued to follow its previous course.

As a result, Stark received two Exocet missiles on board, one of which, fortunately, did not explode. 37 crew members were killed, who then had to fight for survivability in full.

The Phalanx's first real kill occurred in 1996, but it was a situation where things didn't quite go as planned.

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer Yugiri, participating in an air defense firing exercise, somehow inexplicably pointed its Phalanx at a US Navy A-6 Intruder bomber that was towing a target. A-6 was shot down, fortunately, the crew escaped safely.

And finally, the most recent developments: last week, a complete naval battle broke out in the Red Sea, during which the US Navy destroyer Gravely successfully fought off four Houthi anti-ship missiles. And the last, fourth missile was shot down less than a mile from the ship.

In general, the Yemeni guys have tried to attack warships before, but their missiles were shot down by the coalition’s naval missile defense systems long before they could even theoretically hit the ships of Britain and the United States.

But time passed, the Houthis gained combat experience, paying, in general, not with the most modern missiles. And as the coalition forces stretched and the ships' ammunition was used up, the missiles began to fly closer and closer.

And while the crew of the destroyer Gravely fought off the missiles that were flying at it with all their might, and fought back successfully, the Houthis planted a fifth missile on the side of a British cargo ship, which the destroyer was supposed to guard.

On the one hand, this is a victory for the Phalanx, which in almost 40 years of service has not committed a single combat defeat of a target. This is generally good because the system is the last line of defense for Navy ships. Typically, US Navy warships have three or more air defense ranges.

The outer radius consists of the Aegis combat system complete with SM-2 and SM-6 air defense missiles.

The next range is the Evolved Sea Sparrow, and in some cases the 127mm Universal Artillery System.

The third radius is the Phalanx, as well as the SEWIP jamming component and the MK 53 Nulka decoy launch system.

In general, US Navy destroyers have participated in battles before, but this is the first time that an anti-ship missile penetrated to the third air defense radius.

What's next?

It is not easy to draw conclusions. We really don't know what happened in detail, and how it happened that the Houthi anti-ship missiles came close to the destroyer. Did the long-range missiles miss? Did the ship's radar detect them too late?

In general, on the one hand, we now know that the Phalanx can indeed destroy an anti-ship missile, but on the other hand, the two defensive radii of American destroyers are not ideal.

This is undoubtedly useful information both for those who will try to break through the defenses of American ships in the future, and for those who rely on protection. Including the last line of defense - the Phalanx.

Information