From galleons to Dunkirk frigates

The early 1500s are often referred to as the "shipping revolution." The artillery had finally established itself on navy, but brought with it many problems. First of all, this is the distribution of weights. The cannon ports invented by the French, on the one hand, made life easier for the artillerymen themselves, but on the other hand, they became a headache for the sailors.

If the port was too close to the waterline, the ship risked sinking. And vice versa, if the main artillery deck was located high, due to the high center of gravity, the ship simply risked capsizing.

Thus, the famous ship Mary Rose sank due to the fact that its ports were only 40 cm above the waterline and during the list they simply did not have time to slam them shut. On the other hand, the Swedish Vasa had a high center of gravity, tilted during a gust of wind, water rushed into the open gun ports, and the ship sank.

Both Mary Rose and Vasa were large, impressive ships for their time, and embody the ideal "technical error during construction."

Spanish and English fleets

Before 1600, most of the large cannon used on ships came from the army. There were no uniform calibers, and to top it all off, in the first half of the 1530th century, these guns were most often unsuccessfully placed either in the bow or in the stern. Only around the 1540s did the Spaniards, and from the XNUMXs everyone else, begin to distribute cannons along the sides.

The truly naval cannons were the so-called “culverins”, whose barrels were very long, as well as canons and demi-canons. Thus, the Spanish culverin had a caliber of 20 Castilian pounds (1 Castilian pound - 460,093 grams), a barrel length of 4,65 meters and a weight of 70–72 quintals (3,22 tons). The English culverin had more modest characteristics - caliber 17 pounds, barrel length - 2,44 meters, weight - 30 handreveits (1,524 tons).

Spanish canon (cannon) - caliber 36 pounds, length 2,9 meters, weight 50 quintals (2,3 tons). English canon - caliber 30 pounds, barrel length 3 meters, weight - 42 handerweight (2,184 tons).

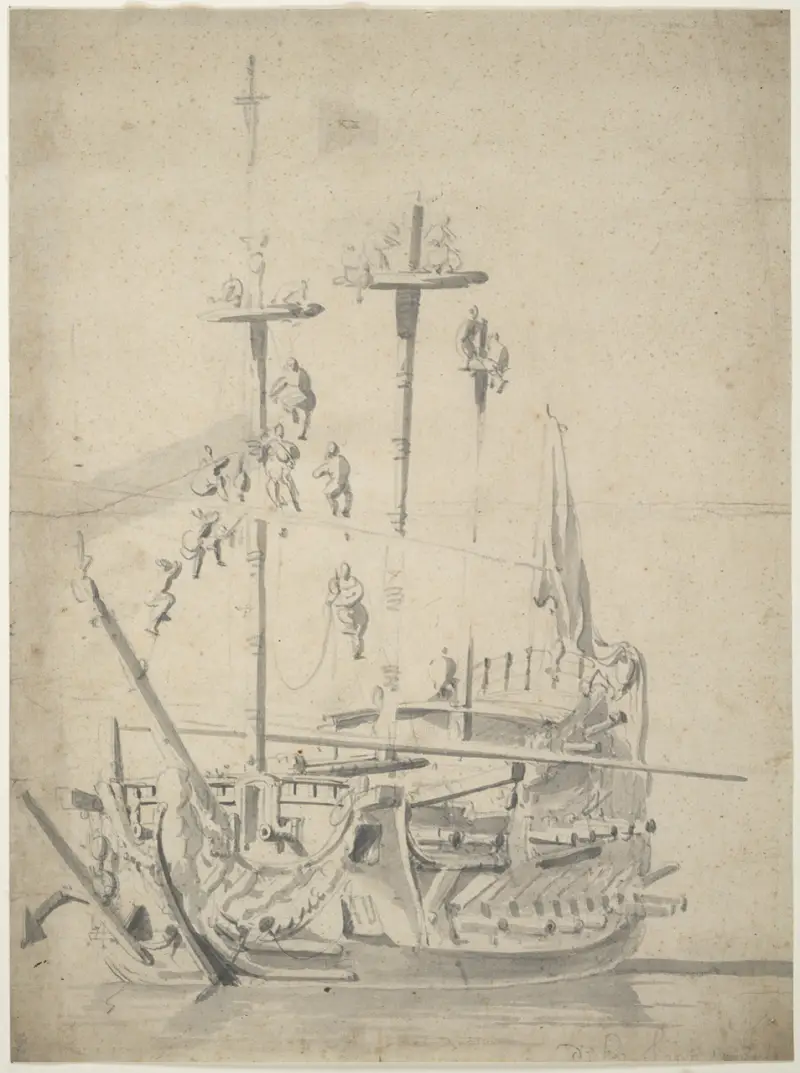

The Spanish Armada off the English coast.

The disparity in the armament of ships is perfectly illustrated by the following examples. For example, the galleon San Martin was armed with 6 canons, 4 demi-canons, 6 stone throwers, 4 culverins, 12 half-culverins, 14 swivel cannons. Of this total, 32 cannons fired iron, cast iron or bronze cannonballs, and 18 fired stone cannonballs.

If you think that the British had more order, you are mistaken. For example, the famous Revenge (built in 1585) carried 2 demi-canons, 4 perrier canons, 10 culverins, 6 half-coulevrins, 10 sacre, 2 falcons, 2 port pisses (10-pounder guns), 4 fowlers, 6 basses. Here it is also necessary to separate the cannons that fired wrought iron cannonballs, cast iron cannonballs and stone throwers.

As for ships, at that time the galleon reigned supreme in the sea. The Spanish fleet of the Armada times can be quite conditionally (adding large naos here) divided into four types of galleons. These are Class I galleons, most often flagships or vice admiral's ships, displacing 1–000 tons, which carried 1 to 200 guns (the Armada had seven); class II galleons, displacing 30 to 50 tons, which carried 750 to 900 guns (30 units); Class III galleons, most of which were assigned to the Biscay and Castilian Armadas, had a displacement of 40 to 30 tons and carried 520 guns (540 units); and finally, class IV galleons, from 24 to 16 tons, which had from 250 to 400 guns (16 units).

Of all these galleons, only the flagship seven were built as warships, the rest were military merchant ships, with spacious holds and a hastily armed menagerie of guns of different calibers.

Model of the English "fast galleon" Revenge, 1577.

As for the British, during this period they developed the so-called “fast galleons”, that is, galleon-type vessels in which the forecastle and sterncastle were greatly reduced, and the length-to-width ratio was 3,5 to 1. “Fast galleons”, in rare cases with the exception, they had a displacement of 150 to 400 tons and carried from 20 to 40 guns.

Nevertheless, in 1588 both Spanish and English ships were still to some extent derivatives of medieval ships.

Dutch experience

In this regard, the Netherlands went its own way. Throughout the 40th century, sailors from Holland, who were mainly engaged in fishing, began to build a new type of vessel, which they borrowed from the Scandinavians and called “busse” (buche, busse). The ships were pot-bellied, small, with a displacement of 80 to XNUMX tons. But the epoch-making innovation in them were the sides heaped inside and a flat bottom.

It was this principle that was used in 1595, when a new type of merchant ship, the flute, was launched in Horn. The ship had a length to width ratio of 4 to 1, a pear-shaped cross-section, inward sides and an almost flat bottom. This ship was the first to have a steering wheel instead of a tiller. To control the steering wheel, the Dutch came up with a scheme of blocks and cables.

The flute usually carried straight sails on the foremast and mainmast and a forward sail on the mizzen. By the way, the length of the masts was increased, and a little later they began to place not two, but three tiers of sails on the masts for ease of control.

Model of a Dutch flute.

The ship turned out to be light, seaworthy, easy to operate; most often, both beads and flutes were built from pine or spruce.

The first flutes had a displacement of 80 to 150 tons, but the project turned out to be successful, and the tonnage began to be increased. Due to the absence of locks in the stern and bow, the center of gravity of the flute was located quite low, the ship turned out to be stable, and naturally, the Dutch thought about its military reincarnation. And soon 400- and 500-ton flutes appeared, armed with 40 or 50 guns.

Privateer frigates

During the Thirty Years' War, the Dunkirk corsairs discovered that galleons and flutes were difficult to operate in shallow waters, and they needed a new type of vessel.

No, at first they tried to make do with galleons and flutes, simply reducing them in size. So, in the 1640s, in the Flemish Armada, a galleon was a ship with 12 to 24 guns, three masts and a displacement of 150 to 300 tons. Slightly smaller ships began to be called “flybots”, in fact, these were flutes with a displacement of 80 to 120 tons, carrying the same 12–24 guns, but at the same time more maneuverable and speedy, due to the increased length (the ratio of length to width became 6 to 1) and three tiers of sails.

In 1634, the strongest galleon of the Flemish Armada had 48 guns and a crew of 300, and of the 21 royal ships at Dunkirk, 14 had only 24–26 guns for a crew of 130–150 men.

It is clear that such characteristics were limited by the depth of Dunkirk harbor. Dunkirk was unable to accept anything more powerful and deep-sea.

Therefore, another thought arose - what if we creatively developed and used the concept of galleys? Spanish masters had been building galleys almost since the 1630th century; they knew how to build them to perfection; moreover, Spanish generals were very fond of galleys. However, rowing was considered a shameful, slavish activity in Spain, and rowers were most often recruited from prisoners. Since by the XNUMXs the Dutch had learned to fight, there were few prisoners. After this, the Dunkirk privateers began, on the orders of Spinola, to capture English ships and send English sailors to the galleys (although England was a neutral power at that time):

But there weren’t enough of them either, so in the Flemish Armada they tried to switch to half-galleys, reducing the number of cans from 20–24 to 7–12. This type of rowing vessel was lighter, requiring only one person per oar, and most often the rowers on them were not criminals or prisoners, but civilian sailors.

Spanish galley of the 17th century.

From the half-galley, the pinnace was born - this is a small sailing and rowing ship with two masts, ten pairs of oars and carrying 10-12 guns, three in the bow, and the rest - light ones - located on the sides. The cannon deck was placed above the rowing row, and this protected the rowers from waves and wind.

It was the pinnace squadron that was commanded in Dunkirk in the 1630s by a certain Gaspard Bar, the uncle of the future famous French privateer Jean Bar.

Well, then the Flemings did the simplest thing. They connected the narrow, pointed profile of the pinnace, removing the oars from there, and installed square-rigged masts on the ship with three tiers of sails on the first two masts. In addition, the oars were also retained, only now the rowing deck was simply removed, and, if necessary, weights began to be inserted into the cannon ports. That is, the ship could either row or use cannons.

Blockade of Dunkirk by the Dutch fleet. Note the pear-shaped stern of the flutes.

The first Dunkirk frigate was built in 1626 by shipwright Jacques Folbier, called La Esperança, had a displacement of 32 tons and carried 6 small cannons. The ship turned out to be exceptionally fast and maneuverable and, of course, it soon began to increase in size, and by 1636 it had reached a displacement of 100–200 tons.

These Dunkirk frigates made a big splash off the Dutch coast, the Dutch wrote:

End

After the capture of Dunkirk in 1646 by the Duke of Enghien, Abraham Duquesne, future admiral of France and conqueror of de Ruyter, was ordered to visit Dunkirk with a commission of inspection. After inspecting the shipyards, he proposed maintaining shipbuilding in the city and starting to build Dunkirk frigates in even greater quantities. Cardinal Giulio Mazarin approved this idea.

On the other side of the English Channel, other events took place. In 1636, the British fell into the hands of a real Dunkirk frigate - Nicodemus (6 guns, 105 tons, length 73 feet, width 19 feet), as the British themselves described it - “the fastest ship in the world” (most absolute sailer in the world).

HMS Constant Warwick, 1645.

English craftsmen creatively reworked the project, greatly increased its size, installed heavy guns, and as a result, in 1645, the first real frigate was laid down - the 32-gun Constant Warwick. But this is completely different story.

References:

1. Patrick Villiers “Les corsaires du littoral: Dunkerque, Calais, Boulogne, de Philippe II à Louis XIV (1568–1713)” – Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2000.

2. Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker “The Spanish Armada” – Manchester Univ Pr., 2002.

3. EW Petrejus “La flûte hollandaise” – Lausanne, 1967.

4. Unger, Richard W. “Dutch Shipbuilding in the Golden Age” – History Today. Vol. 34, No. 1, 1981.

5. H. Malo “Les corsaires dunkerquois et Jean Bart”, volume I – Des origines à 1682. Paris, Mercure de France, 1913.

6. Dr Lemaire, “La frégate, navire dunkerquois” – Bulletin de l'Union Faulconnier, tome XXX, 1933.

7. La Roncière “Histoire de la marine française”, tome IV – Revue d'Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine Année, 1910.

Information