Kentucky rifle, Pennsylvania rifle, long rifle or widowmaker

"Kentucky Rifle"*, ca. 1810 Gunsmith John Spitzer. Maple stock with silver and brass finish. Overall length: 162,3 cm. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

St. John's Wort finally exclaimed. –

It's really a pity that it fell into the hands of women.

The hunters have already told me about him,

and I heard that it brings certain death,

when it is in good hands.

Look at this castle -

even a wolf trap is not equipped with one like this

accurately working spring,

the trigger and the pawl operate simultaneously,

like two singing teachers,

singing a psalm at a prayer meeting.

I've never seen such an accurate sight,

Fidget, you can be sure of that.

James Fenimore Cooper "St. John's Wort, or the First Warpath"

Weapon and people. It often happened that the development of firearms and, in particular, the same rifles, was influenced by factors of a natural geographical nature. For example, the so-called Little Ice Age, a time of global relative cooling on Earth during the 14th–19th centuries, caused a demand for cloth (and the development of cloth making in Europe) and an increased demand for furs, and in particular for beaver pelts. And since there are practically no beavers left on European territory, they began to be hunted in the lands of North America.

Hunters went away from residential areas for a long time, and carried everything they owned, including weapons and ammunition for it, on themselves, so the weight of round bullets began to be of particular importance, as well as the accuracy of each individual shot. Another factor was barter with the Indians. They were also sold guns and demanded in payment for them furs, stacked from the butt to the end of the barrel!

It is clear that the profit from such trade was simply colossal, but it was soon noticed that the accuracy of such guns was much higher than that of relatively short-barreled and large-caliber muskets. Then rifled barrels began to be installed on such guns, which became known among hunters as “deer-killers”**, which further increased the accuracy of such long guns.

A typical "long rifle" with a flintlock. Gunsmith: Henry Young (c. 1775 – c. 1833). Date of manufacture: approx. 1800–1820 Pennsylvania, Easton Township, Northampton County. Material: wood (maple), steel, iron, brass, silver. Overall length: 154,9 cm. Barrel length: 116,5 cm. Caliber: 12,4 mm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

True, initially on the border they preferred long-barreled firearms - a smoothbore musket, which was produced at enterprises in England and France and sent to the colonies for sale. But gradually long rifles became more and more popular due to their longer firing range.

The effective range of a smoothbore musket was less than 100 yards (91 m), while a rifled rifle shooter could hit a man-sized target from a distance of 200 yards or more. True, the price of such accuracy was that reloading a long rifle took much longer.

A case for bullets and wads on the butt of a rifle by gunsmith J. Benjamin Caf. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This, or something like this, is how the famous long rifle was born, which was developed on the American frontier in southeastern Pennsylvania in the early 1700s.

Most likely, this was the work of German gunsmiths who emigrated to the USA and organized the production of hunting rifles here. States such as Pennsylvania, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio and North Carolina became the centers of their production, and they were produced until the 20th century as a very practical and effective firearm for rural areas of the country.

The fact is that they could be made entirely by hand, using the simplest tools, in frontier conditions.

Long rifle of George Schreyer the Elder (1739–1819). Date of manufacture: approx. 1795 Pennsylvania, York County. Material: wood (maple), steel, iron, brass, silver. Total length: 153 cm. Barrel length: 115,3 cm. Caliber: 12,7 mm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In his book, The Kentucky Rifle, Captain John G. W. Dillin wrote the following about it:

Light in weight; graceful in formation; economical in the consumption of gunpowder and lead; deadly accurate; clearly American; she immediately gained popularity; and for a hundred years the model was often slightly varied, but never radically changed.”

Well, she got her nickname “Kentucky Rifle” in honor of the popular song “Kentucky Hunters”, dedicated to the victory at the Battle of New Orleans during the war with England in 1812.

As noted here, the smaller caliber*** required less lead per shot, which reduced the weight the shooter had to carry; a longer barrel gave the black powder more time to burn, which also increased the muzzle velocity and accuracy of the shot.

As a result, the accuracy of shooting from the Kentucky was simply fabulous for those times: at shooting competitions, trappers at a distance of 150–200 meters from this rifle could easily cut off the head of a turkey with a bullet! A typical rifle of this design had a 42-inch (1 mm) to 100-inch (46 mm) barrel, .1 caliber (200 mm) and a curly maple stock that went all the way to the end of the barrel. The butt was shaped like a crescent.

From an artistic point of view, the "long rifle" is known for its elegant stock, often made of curly maple, with its elaborate decoration, decorative inlays and a built-in bullet and wad case with a securely locking brass lid, and was one of the most beautiful examples of firearms of the 18th century. – beginning of the 19th century.

A rule of thumb used by some gunsmiths was to make the rifle no longer than the customer's chin so that he could see the muzzle while loading, especially since a long barrel allowed for better aim. It is therefore not surprising that by the 1750s it was common to see frontiersmen armed with just such rifles.

By the way, it was at that time in 1755 that the “long rifle” passed its first test in battle with the regular army. Then 400 settlers, armed with these rifles, attacked the French fort Duquesne on the Monongahela River. The French lined up in battle formation, but... only they had no one to fight with, since the enemy was not visible, and only bullets, arriving from somewhere unknown, mowed down the French soldiers one after another. Volleys fired into the forest yielded nothing, since the French bullets simply did not reach the settlers holed up in it.

As a result, practically without losses (7 were wounded, one himself broke his leg), the detachment calmly returned back.

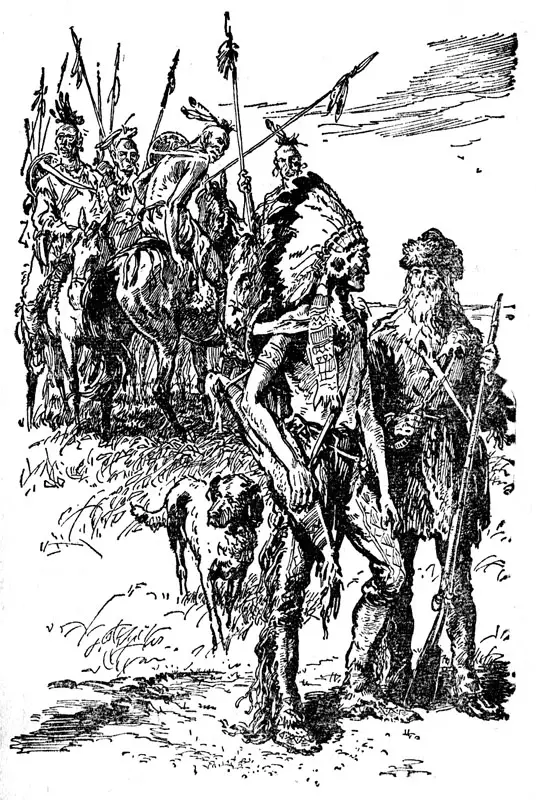

Indian and white hunter with Kentucky Rifle. Illustration from J. Fenimore Cooper's novel The Prairie. State Publishing House of Children's Literature, Moscow, 1962.

In Pennsylvania, the earliest gunsmiths known to have produced long rifles were Robert Baker and Martin Meylin, who began production in 1729.

There is also documentation that the first high-quality long rifles were made by a gunsmith named Jacob Dickert, who moved with his family from Germany to Berks County, Pennsylvania in 1740. Moreover, the name “Dickert Rifle” became its “trademark” over time.

They were produced in ever-increasing quantities, so that by 1750 it was common to meet a border resident with just such a rifle.

In 1792, the US Army shortened its barrel length to create the Model 1803, which became known as the "Plains Rifle." Originally a very simple long rifle, by the 1770s they began to decorate with applied and embedded parts made of brass and silver, and also cover metal surfaces with engraving. Flintlocks were usually purchased in bulk in England, but gradually they began to be produced in the colonial states themselves.

During the Revolutionary War (1776–1789), it turned out that American militia, being out of range of the British Brown Bess smoothbore musket, successfully hit individual British soldiers and officers from a great distance. George Washington was very glad that his men were armed with Pennsylvania rifles, although most soldiers still used the musket because it was much easier and faster to load in battle.

But an American sniper with his long rifle could easily shoot the British general, who thought he was safe because he was far enough from the battlefield. The English generals were indignant that the uncouth American border guards, wearing shirts that hung down to their knees, shot at patrolmen and officers from extremely long distances.

In this regard, one of the generals ordered the capture of such a shooter in order to look at his weapon. The raiding party brought in Corporal Walter Crouse from York County, Pennsylvania, with his “long rifle.” And this is where the British made a serious psychological mistake by not fully thinking through the consequences of their next step.

And this is what they did: they sent the captured shooter to London.

And there, Krause, who was ordered to demonstrate his remarkable weapon in public, began to hit targets every day at a distance of 200 yards, which was four times the practical range of a smoothbore military shotgun of that time.

It turned out that this was bad PR, as the story goes that recruitment immediately stopped following these demonstrations, and King George III was forced to hire Hessian marksmen to fight the American sharpshooters. Then, by the way, she was also nicknamed “the widowmaker”!

When cap locks came into use, “Kentucky rifles” with cap locks also appeared. Photo of Rock Island Auction Company

True, in a situation where hand-to-hand combat could occur, the “long rifle” turned out to be too fragile to be used as a club. A blow to a hard object, such as someone's head, could easily result in the stock breaking. The long, thin wrought iron barrel was relatively soft and could bend easily.

The Americans knew about this and tried not to damage their main hunting weapon. In battle, reloading a Kentucky rifle also took twice as long as reloading a Brown Bess musket.

In addition, due to the length of the barrel, the shooter almost always had to stand up to carefully measure the powder and load the bullet. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Pennsylvania riflemen, for example, hid behind trees so as not to expose themselves to the danger of being hit by enemy fire, and the tactics of that time did not at all approve of this behavior of soldiers.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the main weapon during the revolutionary war on both sides was the Bran Bess smoothbore musket, as, indeed, in the war against Napoleon. And only less than 10% of American soldiers carried long rifles. However, this was enough for everyone to see the undeniable benefits of rifled weapons in the army!

*This rifle had several names, and the name depended on where it was used. But no matter what it was called, the Kentucky Rifle, the Southern Poor Man's Rifle, or the Tennessee Rifle, many of them were made in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

**This is exactly the gun that the legendary Nathaniel Bumppo, the hero of the Leatherstocking novel series by the American writer James Fenimore Cooper, owned.” They say that Bumpo hunted and fought with a gun with an unusually long barrel. He received this weapon as a gift from Judith Hutter in the novel "Deer Killer", and the Indians call it "Long Carbine", which seems to indicate its rifled barrel, and the hunter himself calls it "Deer Killer" and does not mention anywhere that it rifled. However, judging by the fact that he loads it with a bullet with a soft leather patch, it can be assumed that this “deer-killer” could well be a German hunting rifle with straight rifling. Just the same ones that were used at the beginning of the 17th–18th centuries.

***The calibers of the Kentucky Rifle ranged from .50 to .40 (12,7 to 10 mm), and sometimes even .38 (9 mm). But they were all smaller than the army ones.

Information