Two shipbuilding methods

Since the beginning of time

The question that we will raise in this article is a controversial and ambiguous issue, on which not only historians, but also shipbuilders are still debating, but which is not only important for understanding the shipbuilding of the times of sail, but also incredibly interesting.

And this question sounds like this: what is the best way to build a ship? First create its skeleton, and then cover it with boards, or first create a “skin”, a “shell”, which is then reinforced with a skeleton?

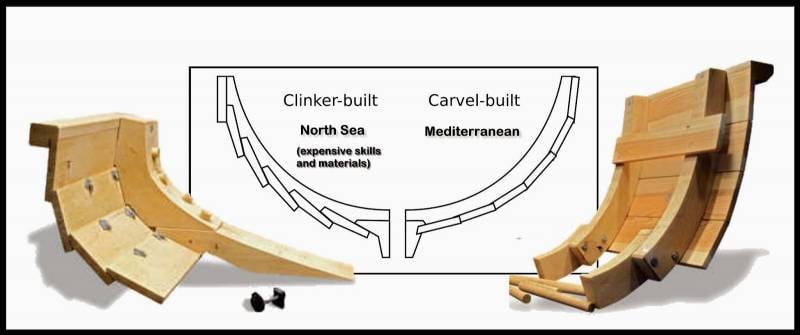

It must be said that initially, both in the Mediterranean Sea and in the rest of the world, ships were built in the second way - first by creating a “shell”, and then strengthening it with frames. It’s just that the methods of attaching the boards of this “shell” varied. If in the Mediterranean the boards were fastened joint to joint, then in Western and Northern Europe they were overlapped. The first method was called carvel cladding, the second - clinker.

Clinker (left) and carvel (right) method of fastening the cladding

Around the XNUMXst century BC. e. The Romans took a step forward - they first began to create the skeleton of the ship, that is, the keel, frames, etc., and then sheathed this skeleton with boards using carvel technology. Several factors contributed to this. First of all, the development of mathematics and geometry, as well as the invention and production of saws, which could be used to cut boards of the required size and thickness. This method of shipbuilding was established throughout the ancient world on the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic coast approximately to the level of the Portuguese Douro River. All areas to the north used the clinker technology method.

What was he like? This method originates from single-tree boats. In ancient times, they took a large log, hollowed out the core, then filled the hollowed-out space with water, and placed such a dugout over the fire in order to steam the wood and spread the sides, inserting spacers. It is clear that during this procedure the sides were lowered down, and their height had to be increased, for which boards were added to them at full length. Since these boards were made by people who did not know saws, they were obtained from logs using a cleaver or an ax. This method was called barbaric, in defiance of the carvel lining, called Roman or ancient.

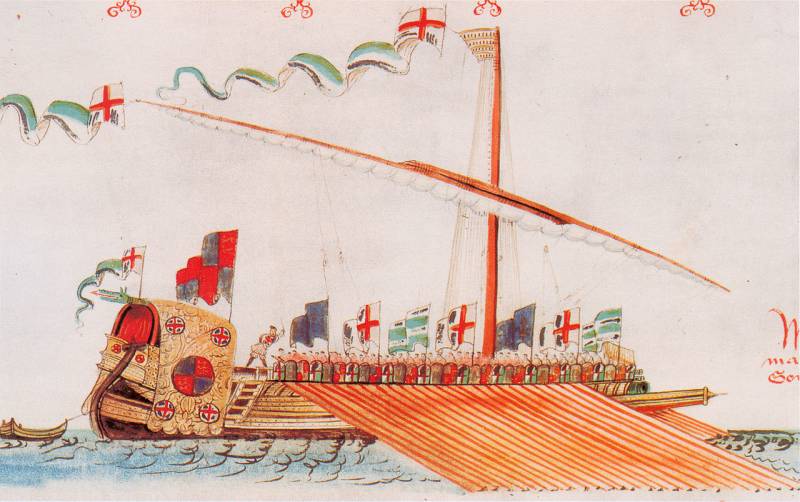

But, oddly enough, initially ships made using the clinker method were stronger and more seaworthy. This is due to the fact that clinker was invented by peoples who settled in stormy and harsh seas (the Bay of Biscay, the North and Baltic Seas), while the Roman method was suitable for the softer Mediterranean Sea and was initially used in the production of various types of galleys, that is, ships with low silhouette and lighter. Galleys in the Nordic countries were difficult to use not only because of their limited seaworthiness and loading capacity, but also because of limited human resources. The Romans sent slaves as rowers to the galleys, whom they captured in large numbers in their endless wars. Any Britons or Germans could not afford such luxury.

Reconstruction of a Roman galley. The skin is clearly visible

It must be said that both of these methods existed independently of each other for quite a long time. The only innovation that all sailors introduced by the beginning of the XNUMXth century was a composite keel, which made it possible to increase the size of ships. But even in the XNUMXth century, northern peoples first collected the “shell” and then built up the skeleton. For the keel, a particularly long and strong tree was selected, the bow and stern stems were attached to it, and then the skin was assembled overlapping from the bottom to the sides, and only after final assembly the fasteners and frames were installed.

Coggs and carracks

However, in the XNUMXth century, the Germans developed new types of ships - coggs. Cogg differed from previous versions of the ships in that its frames protruded beyond the side line, the steering oars were replaced by a tiller and rudder, and in the bow and stern, in order for the crew to wait out bad weather, a forecastle and sterncastle were built - bow and stern superstructures. Soon their main function became to station archers and javelin throwers against possible boarding by pirates' rowing ships. The high side of the cogg was difficult to storm from below, especially since the gunners on the superstructures and the top were literally knocking out the boarding teams from top to bottom.

New ships quickly spread throughout the countries of Northern and Western Europe, and, for example, in the battle of Sluys in 1340, it was the coggs that formed the main striking force of both the English and French fleets.

In the middle of the XNUMXth century, coggs gradually began to give way to carracks. The birthplace of this type of ship was Genoa, but the Northern Europeans did not copy, but reworked the Genoese design, combining it with the cogg.

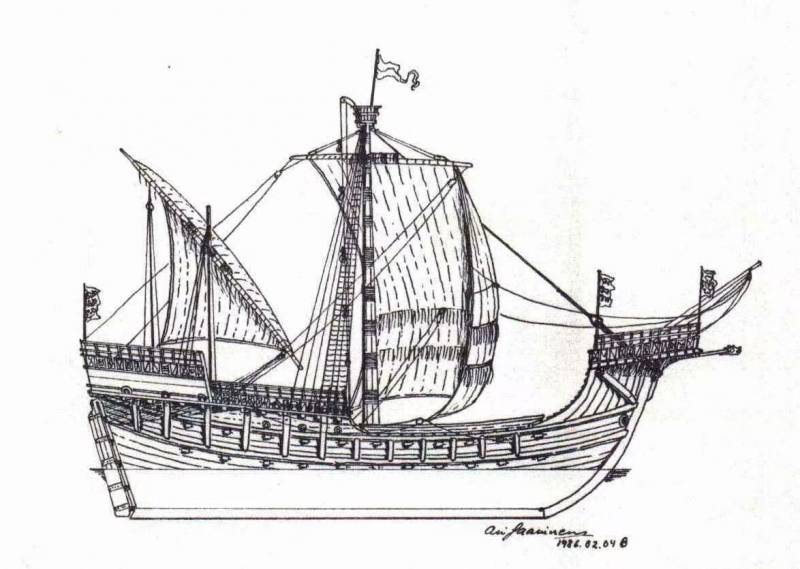

Reconstruction of a Hanseatic cogg

Unlike the cogg, in the karakka the skeleton of the ship was first assembled from the keel and frames, which was then sheathed with boards, naturally, using the carvel method. Next, the joints between the boards were caulked, and voila, the body is ready. The northern countries greatly appreciated the construction from the skeleton to the skin, only the skin was fastened in the old fashioned way not smoothly, but overlapping. If the coggs had a displacement of 200-300 tons, then the karaks had a displacement of 400-500 tons. But the increase in the weight of the ship led to the fact that with conventional masts it had virtually no speed, so super-long and strong trees were initially sought out for karakkas. However, sequoia does not grow in Europe, so soon carracks began to be equipped with two masts.

The British “met” the carracks in 1413, when the next round of the Hundred Years’ War began. The French hired them from the Genoese to raid the British Isles. The English coggs were not in a very good position in the clashes - the carracks were larger and taller, and carried more warriors. However, with the help of English archers, the British were able to capture 8 French carracks and immediately wanted to build something similar.

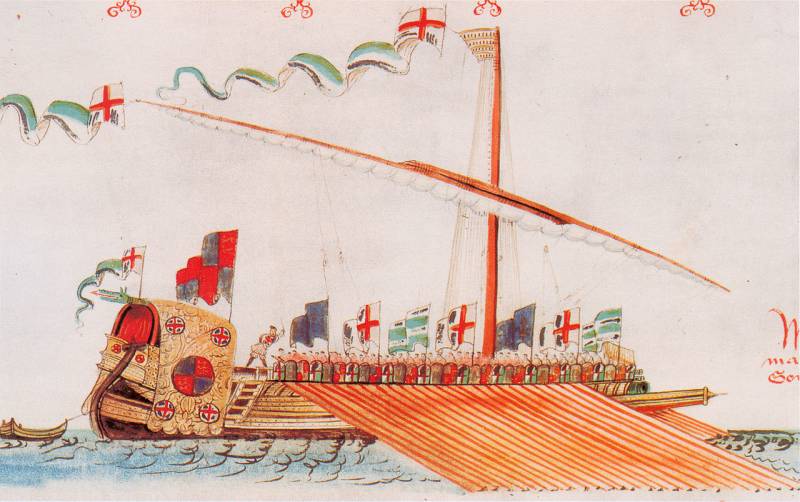

The first carracks in England were built in 1416, and they were initially built the old fashioned way - a composite keel, a hull set from bottom to top, and only then frames and fastenings. Holigost, Jesus and the giant Grace Dieu (1400 tons) were built according to this type, and the latter had a triple skin. Since Grace Dieu could not “carry” two masts, they also installed a third mast – a mizzen. This, however, did not prevent the ship from leaving the sea, and its first attempt to leave ended in a mutiny by the crew.

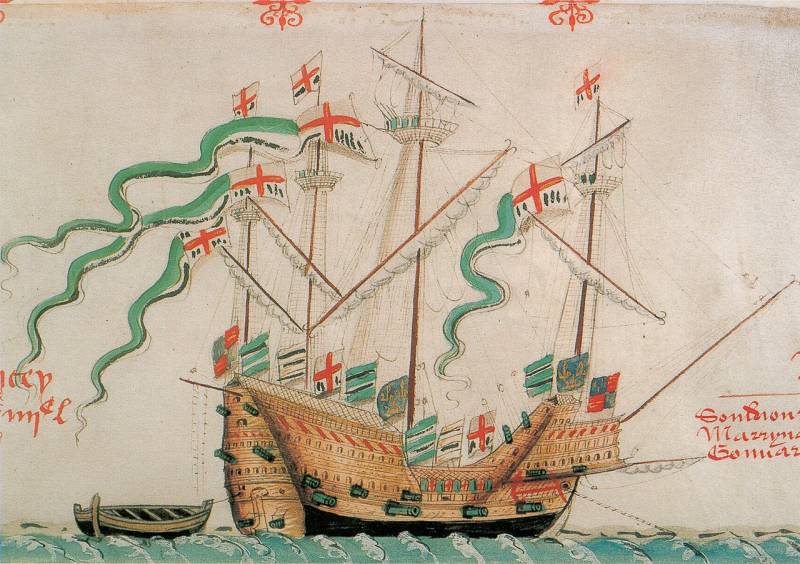

Caracca Grace Dieu (1418)

Despite such large-scale construction fleet, Henry V decided the struggle for supremacy at sea on land - at Agincourt.

Transition to carvel technology

And here we should start with Spain. The fact is that the year 1425 became a watershed there. Until this time, the main shipbuilding facilities of the Kingdom of Castile and Leon were located in Cantabria, in the Four Cities of the Sea - Santander, San Vicente de la Barquera, Laredo and Castro Urdiales. The Cantabrians built ships using clinker technology, which was no different from European countries. However, in 1425, a series of fires occurred at the shipyards, in which not only the buildings burned down, but also a lot of supplies and prepared materials.

As a result, the center of Spanish shipbuilding moved to Seville, Cadiz and Cartagena, which built ships in the Mediterranean tradition. Around this time, Spanish shipbuilders introduced an innovation that would later spread carvel technology north. Since single carvel cladding was less durable than clinker, they began to make it double, and the cladding boards were arranged in a checkerboard pattern, which increased the strength of the hull many times over. At the same time, instead of one large sail on the masts, they began to install two smaller sails, which made it easier for the team to work with the sails.

What about England?

In 1419, English troops captured Rouen, where the main French shipyard for the construction of galleys and small ships was then located. Genoese and French craftsmen were also captured there; in 1423 and 1424 they built several ships for England according to their own designs, and only in 1436 the British were able to reproduce a similar ship, later this type was called the “Genoese carrack”. It was these carracks that turned out to be the first ships built according to the Mediterranean method - first the skeleton in the form of a keel and frames, then the plating.

The first English "Genoese carrack" launched had a displacement of 600 tons and was called "Libelle Englyshe Polycye". The six “Genoese carracks” had two masts, which was a novelty for the British at that time, but the problem, as it turned out, was not even in the construction, but in ongoing repairs. Already in 1424, the chief carpenter wrote to the king:

That is, the problem was that the British simply did not know how to fasten the skin smoothly.

English galleas of Mediterranean type

As a result, the Venetians and Genoese were hired, who carried out routine repairs of the ships, while delighting the English craftsmen with a new method of heeling, that is, to clean and repair the bottom, the Italians simply tilted the ships on one side or the other. But it was impossible to contact them constantly. Moreover, the cost of repairs exceeded the usual fourfold.

As for caravels, they appeared in Northern Europe in 1438-1440. The first caravel was built in Sluys by the Portuguese shipbuilder Jehan Perouse. The British had ships of this type only in 1448, when master Claes Stephen received money from the king for construction

That is, it was the 1450s that became the time when the British finally mastered the carvel method of shipbuilding. From 1453 to 1466, 20 flat-planked caravels were built in England, but all other ships were built using the clinker method.

However, with the introduction of artillery into the fleet, everything turned upside down. A century earlier, galleys irrevocably lost a naval battle to sailing ships, and then... after they decided to install artillery on sailing ships, it turned out that only light cannons could be placed there (because initially they were placed on superstructures - out of habit, to shoot from top to bottom), because otherwise problems with stability began. And the rollback of the guns - there was simply no room for it on the ships. On the galleys there was no such problem - the guns were placed in the bow, and the rollback could be of any kind - from the bow along the rowers' banks all the way to the mast. As a result, in 1513, near Brest, a detachment of French galleys without the slightest difficulty broke through the formation of the English sailing fleet, sinking one ship and seriously damaging another.

Attempts to install larger guns on superstructures led to disasters - in fact, this is how the karakka Mary Rose sank. The irony of fate is that we now know and study shipbuilding of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries using the worst examples - Mary Rose and Vasa.

In order to somehow counteract the galleys, the British began to build galleasses - essentially these were sailing and rowing ships with a superstructure and increased artillery weapons.

Karakka Pansy

Well, then the British gained invaluable experience. In 1553, Queen Mary Tudor ascended the throne of England and the following year married Prince Philip of Spain, the future King of Spain, Philip II. In 1555, Spain's relations with France began to deteriorate. England was in an alliance with Spain, and therefore the queen (or rather Philip of Spain) decided to restore the English fleet. Philip invited, among other things, Spanish and Flemish shipwrights to England. Since 1556, the well-known Bernardo de Mendoza, captain-general of the galleys of Spain, the hero of the landings in Algeria and the leader of the capture of Mahdia (1550), worked as a consultant at the shipyards of England since 1554. From 1557 to 4, 5 royal ships were laid down according to Spanish designs and 5 ships were rebuilt (one of the ships built by the Spaniards, Lion, served with reconstructions right up to the end of the XNUMXth century). Moreover, the quartet exactly repeated the design of the Spanish galleons with smooth plating, had two decks, that is, two closed artillery decks, and XNUMX were rebuilt from useless galleasses into galeonsetes (small galleons). English craftsmen were able to get acquainted with the principles and features of Spanish shipbuilding.

It was from this time that English shipbuilding finally switched to carvel technology and the construction of a ship from the skeleton to the planking.

References:

1. Fernández Duro, Cesáreo “Armada Española desde la Unión de los Reinos de Castilla y Aragón” -Museo Naval de Madrid, Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval, Madrid, 1972.

2. HR Fox "English Seamen under the Tudors", - London, 1868.

3. William Laird Clowes, Clements Robert, Sir Markham “The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present” - Chatham Publishing; Reissue edition, 1997

4. de Casado Soto, José Luis “Arquitectura naval en el Cantábrico durante el siglo XlIl” - Altamira, 1975.

5. Olesa Muñido, Felipe “La organización naval de los estados mediterráneos, y en especial de España durante los siglos XVI y XVII” - Madrid, 1968.

6. Phillips, Carla Rahn “Six Galleons for the king of Spain. Imperial Defense in the Early Seventeenth Century" - "The John Hopkins University Press", Baltimore and London, 1986.

7. Eriksson, N. “Between Clinker and Carvel: Aspects of hulls built with mixed planking in Scandinavia between 1550 and 1990” - Archaeologia Baltica, 14(2): 77-84.

8. Dotson, J. E. “Treatises on Shipbuilding Before 1650. Cogs, Caravels and Galleons. The Sailing Ship 1000-1650" - London, 1994.

9. Hutchinson, G. “Medieval Ships and Shipping” - London: Leicester University Press, 1994.

Information