India's nuclear arsenal today

Collecting and analyzing accurate information about India's nuclear forces is more challenging than for many other nuclear-armed states. India has never disclosed the size of its nuclear arsenal, and Indian officials do not regularly comment on the capabilities of the country's nuclear capabilities. While some official information may be gleaned from parliamentary inquiries, budget documents, government statements and other sources, India generally maintains a culture of relative opacity regarding its nuclear arsenal.

Previously, India refused to disclose the cost of some nuclear weapons programs. weapons, and in 2016, the Indian government added the Strategic Forces Command, the agency responsible for managing the country's nuclear arsenal, to the list of security organizations exempt from India's Right to Information law.

In the absence of official information from the Indian government and military, local news and the media tends to embellish details about the country's nuclear arsenal; for example, some media outlets regularly claim that certain weapons systems are “nuclear capable” despite the absence of any official evidence to that effect.

To this end, we generally rely on official sources—as well as commercial or freely available satellite imagery—to analyze India's nuclear arsenal and, whenever possible, attempt to confirm the veracity of any unofficial claims through multiple sources. In particular, the research of open source analysts like @tinfoil_globe has proven to be very valuable in analyzing Indian military bases using satellite imagery.

India continues to modernize its nuclear weapons arsenal and is rushing to operationalize the nascent triad.

India currently has eight different systems capable of carrying nuclear weapons: two aircraft, four land-launched ballistic missiles and two sea-launched ballistic missiles. At least four more systems are in development, most of which are believed to be nearing completion and will be ready soon. Beijing is now within range of Indian ballistic missiles.

India is estimated to have produced approximately 700 kilograms (give or take 150 kilograms) of weapons-grade plutonium, enough to produce between 138 and 213 nuclear warheads (International Panel on Fissile Materials, 2022); however, not all of the material was processed into nuclear warheads. Based on available information on the structure and strategy of the nuclear delivery force, India has produced 160 nuclear warheads. The Indian military will need more warheads to arm the new missiles it is currently developing.

The source of weapons-grade plutonium in India was the operating Dhruva plutonium production reactor at the Bhabha Atomic Research Center complex near Mumbai, and until 2010, the CIRUS reactor at the same location. India plans to significantly expand its plutonium production capacity by building at least one more plutonium production reactor. Moreover, the 500-megawatt prototype fast breeder reactor (PFBR) being built at the Indira Gandhi Atomic Research Center near Kalpakkam has the potential to further boost India's plutonium production capacity.

PFBR was originally planned to reach criticality in 2010; however, it is marked by significant delays and is expected to reach a critical point by October 2022 (Government of India 2021a). The director of the research center additionally stated that six more fast breeder reactors will be commissioned over the next 15 years. It is known that the construction of the first two, which will be located on the territory of the center, will begin in October 2022 and it is planned to put them into operation by the early 2030s (World Nuclear News 2022).

Nuclear doctrine

Tensions between India and Pakistan represent one of the most troubling nuclear flashpoints on the planet. The two nuclear-armed countries engaged in open hostilities as recently as November 2020, when Indian and Pakistani soldiers exchanged artillery fire over the Line of Control, killing at least 22 people.

The clash followed another incident in February 2019 when Indian fighter jets dropped bombs near the Pakistani town of Balakot in response to a suicide bombing carried out by a Pakistan-based militant group. In response, Pakistani planes shot down and captured the Indian pilot and brought him back a week later. The skirmish turned nuclear when it prompted the convening of the Pakistan National Command, the body that controls Pakistan's nuclear arsenal.

Speaking to the media at the time, a senior Pakistani official noted:

In this context, the risk of escalation of the conflict between India and Pakistan remains dangerously high.

In March 2022, the Indian missile team carried out an unauthorized launch of a ground-launched cruise missile "BrahMos" at a range of 124 kilometers into Pakistan, causing damage to civilian property. Pakistani officials subsequently said India did not warn them through a high-level military hotline, and India did not make a public statement about the accident until two days later.

Although the BrahMos is a conventional weapon, the unprecedented incident - as well as India's inadequate response - has serious implications for the crisis in stability between the two countries. In the absence of any de-escalation measures from India, Pakistan is reported to have suspended all military and civil aircraft flights for nearly six hours and withdrawn forward bases and strike forces. Aviation into a state of high alert. If the same accidental launch had occurred during a period of heightened tension, it is possible that the incident could have escalated into a very dangerous phase.

While India's primary deterrence relationship is with Pakistan, its nuclear modernization indicates that it is placing increased emphasis on its future strategic relationship with China. In November 2021, the then Chief of Defense Staff of India said in a press conference that China has become the biggest threat to India's security (September 2021). Moreover, almost all of India's new Agni missiles have ranges that suggest their primary target is China.

This position was likely strengthened after the Doklam standoff in 2017, during which Chinese and Indian troops were put on high alert over a dispute near the border with Bhutan. Tensions remained high in subsequent years, especially after another border skirmish in June 2020 that left both Chinese and Indian soldiers dead.

More casualties have been reported from Sino-Indian military clashes as recently as January 2021.

The expansion of India's nuclear forces against a militarily superior China in terms of both conventional and nuclear forces will lead to the deployment of significant new capabilities over the next decade. This development could also potentially impact how India views the role of its nuclear weapons against Pakistan. The power requirements India needs to effectively threaten assured retaliation against China may allow it to pursue more aggressive strategies—such as escalating dominance or the “magnificent first strike”—against Pakistan.”

India has long maintained a policy of no first use of nuclear weapons.

This policy, however, was weakened by India's announcement in 2003 that it could potentially use nuclear weapons in response to a chemical or biological attack, which would therefore constitute first use of nuclear weapons, even if carried out in retaliation .

Moreover, during the border skirmishes with Pakistan in 2016, then Indian Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar made it clear that India should not “bind” itself to a no-first-use policy. Although the Indian government later explained that the minister's remarks reflected his personal views, the debate highlighted the conditions under which India would consider using nuclear weapons.

Current Defense Minister Rajnath Singh has also publicly questioned India's future commitment to the no-first-use policy, tweeting in August 2019 that "India strictly adheres to this doctrine. What happens in the future depends on the circumstances."

Recent studies have also questioned India's commitment to a no-first-use policy, with some analysts arguing that "India's NFU [no-first-use] policy is neither a stable nor a reliable predictor of how Indian military and political leadership might actually use nuclear weapons."

Despite questions about the future of India's NFU policy, it could somewhat limit the scope and strategy of India's nuclear forces during the first two decades of its nuclear era.

Additionally, while it has long been believed that India keeps its nuclear warheads separate from deployed launchers, some analysts have suggested that India may have increased the readiness of its arsenal over the past decade by "pre-matching" some warheads to ballistic missiles deployed on launchers. installations, and possibly also storing some bombs at air bases.

There is still uncertainty about the day-to-day readiness of the arsenal as the missiles - Agni-V and Agni-P - are not yet operationally deployed. But this trend is likely to accelerate with the deployment of land-based launchers and India's development of the naval component of its nuclear triad.

Aircraft carrying nuclear weapons

Fighter-bombers were India's first and only nuclear strike force until 2003, when the first Prithvi-II ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead was deployed. Despite significant progress since then in developing a diverse arsenal of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles, airpower continues to play a prominent role as a flexible strike force in India's nuclear policy. According to American experts, three or four squadrons of Mirage 2000H and Jaguar IS aircraft at three bases are carrying out nuclear strikes on Pakistan and China.

Mirage 2000H Vajr (Divine Thunder) fighter-bombers are deployed with the 1st, 7th and possibly 9th squadrons of the 40th Airlift Wing at the Maharajpur Air Force Base (Gwalior) in the northern region of Madhya Pradesh. One or two of these squadrons have a secondary nuclear mission. Indian Mirage jets also occasionally fly from Nal Air Force Base (Bikaner) in western Rajasthan, and other bases could also potentially function as nuclear weapons dispersal bases.

The Indian Mirage 2000H was delivered by France in 1983–1984, which used its domestic version (Mirage 2000N) as a nuclear weapons carrier for 30 years until its decommissioning in the summer of 2018. India's Mirage 2000H is being upgraded to extend its service life and enhance its capabilities, incorporating new radars, avionics and electronic warfare systems; the upgraded version is called Mirage 2000I.

Although the modernization program for 51 Mirage 2000I aircraft was scheduled to be completed by the end of 2021, the program is behind schedule, with only about half of the aircraft upgraded by the expected date. India also intends to purchase 24 Mirage 2000 aircraft, which were previously retired from the French Air Force, and will use the spare parts obtained to maintain the existing Mirage squadrons of the Indian Air Force.

The Indian Air Force also operates four squadrons of Jaguar IS/IB Shamsher (Sword of Justice) aircraft at three bases (a fifth squadron operates the naval version of the IM). These include the 5th and 14th squadrons of the 7th Wing at the Ambala Air Force Base in northwestern Haryana, the 16th and 27th Squadrons of the 17th Wing at the Gorakhpur Air Force Base in northeastern Uttar Pradesh, and 6 and 224 Squadrons of the 33 Wing at Jamnagar Air Force Base in southwest Gujarat.

One or two squadrons at Ambala and Gorakhpur (one at each base) could be assigned the task of a secondary nuclear strike. Jaguar aircraft also occasionally fly from Nal Air Force Base (Bikaner) in western Rajasthan. The Jaguar, developed jointly by France and Britain, was capable of carrying nuclear weapons when used by those countries.

The Jaguar is aging and could soon be retired from its nuclear mission - if it hasn't already. Half of the Jaguars have received the so-called DARIN-III precision attack and avionics upgrade since 2017, but the upgrade for the other half of the fleet was canceled in August 2019 due to its prohibitive cost. Instead, as mentioned, the Air Force will gradually reduce its Jaguar fleet over the next 15 years.

In October 2019, the Indian Air Chief Marshal stated that the Indian Air Force's six Jaguar squadrons, comprising approximately 108 fighter-bombers, would begin to retire in early 2020; however, this deadline may have been pushed back to 2024 to bring India closer to its goal of maintaining enough squadrons to simultaneously deter Pakistan and China over the coming decade.

On September 23, 2016, India and France signed an agreement for the supply of 36 Rafale aircraft. The order has been significantly reduced from the original plans to procure 126 Rafales. The Rafale is used for nuclear missions by the French Air Force, and India could potentially convert it to serve a similar role in the Indian Air Force, with an eye toward taking on an airborne nuclear strike role in the future.

The Indian Defense Minister officially received the first Rafale (tail number RB-001) at a special ceremony in France in October 2019, followed by two more a month later. After initial delays due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent restrictions in France and India, full delivery of 36 aircraft was completed on schedule by April 2022.

All 36 Rafale aircraft are equipped with 13 "India-specific enhancements" which include new radars, cold weather engine starting, 10-hour flight data recorders, helmet-mounted sights, and electronic warfare and identification friend or foe systems. "

The Rafales are deployed in two squadrons of 18 fighters and four two-seat trainers: one squadron (17 Golden Arrows Squadron) at Ambala Air Base, located just 220 kilometers (137 miles) from the Pakistani border, and another squadron (101 Squadron "Falcons of Chamba and Akhnoor") at Hasimara Air Force Base in West Bengal. Both bases are building new infrastructure to accommodate the aircraft, and the Indian Air Force has restored the squadrons to combat readiness after both were decommissioned several years earlier (Indian Air Force, 2021).

Ground-launched ballistic missiles

India has four types of land-based ballistic missiles carrying nuclear warheads in service: short-range Prithvi-II and Agni-I, medium-range Agni-II and Agni-III. At least three other Agni missiles are in development and close to deployment: the medium-range Agni-P, the medium-range Agni-IV, and the limited intercontinental range Agni-V.

It remains to be seen how many of these types of missiles India plans to keep in its arsenal. Some of these could serve as technology development programs for longer-range missiles. While the Indian government has made no announcements regarding the future size or composition of its ground-based missile force, short-range and reserve missile types could potentially be phased out, with only medium- and long-range missiles deployed in the future to provide a mix of strike options Pakistan and China. Otherwise, the government appears to be planning to field a diverse missile force that will be expensive to maintain and operate.

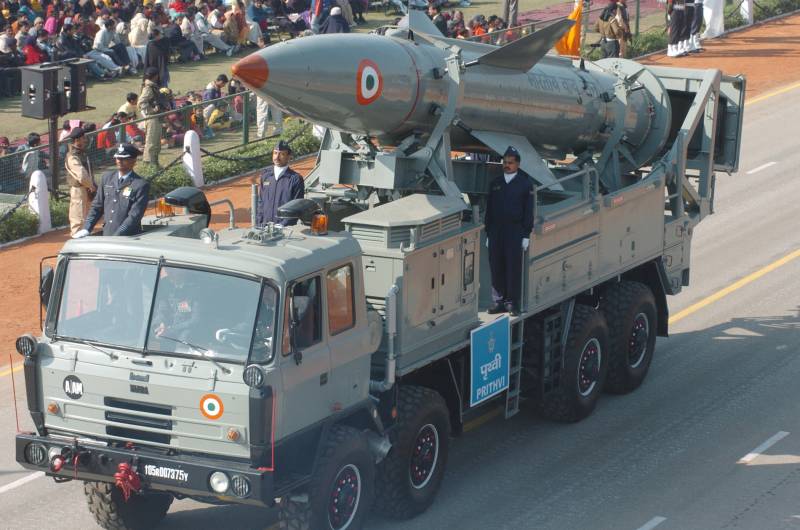

According to the government, the Prithvi-II missile was “the first missile developed” under India’s Integrated Guided Missile Program for “Indian nuclear deterrence” (Press Information Bureau, 2013). The missile can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a range of up to 350 kilometers. Given the relatively small dimensions of the Prithvi missile - nine meters in length and one meter in diameter - the launcher is difficult to detect in satellite imagery, so little is known about its locations.

India is believed to have four Prithvi ballistic missile battalions (222nd, 333rd, 444th and 555th) with about 30 launchers, all deployed near the border with Pakistan. Possible locations include Jalandhar in Punjab, and Banar, Bikaner and Jodhpur in Rajasthan.

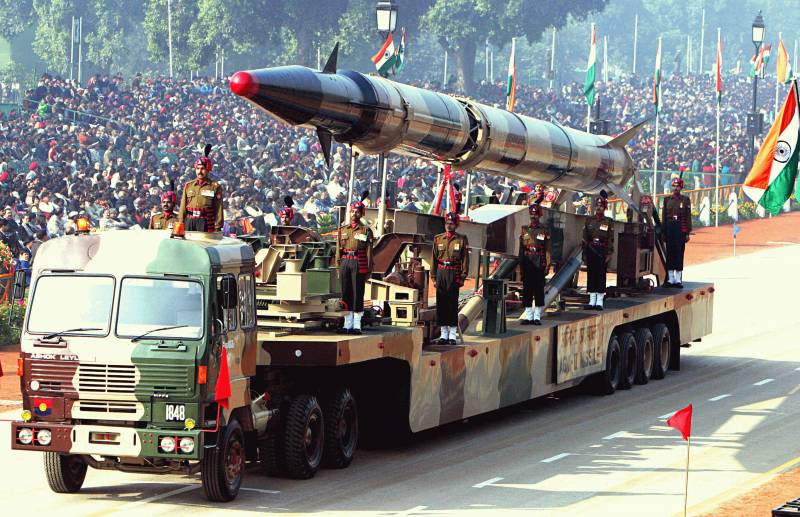

The Agni-I two-stage solid-propellant mobile (SGRK) operational-tactical missile entered service in 2007. A short-range missile can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a distance of approximately 700 kilometers. The Agni-I mission is believed to be aimed at missile attacks on military targets inside Pakistan, with up to 20 launchers deployed in western India, possibly including the 334th Missile Division. In September 2020, India used the Agni-I booster (first stage) to test its experimental scramjet-powered hypersonic guided warhead.

The Agni-II two-stage solid propellant mobile MRBM, an improved version of the Agni-I, can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead over a distance of more than 2 kilometers. The missile entered service in 000, but technical problems delayed its combat readiness until 2008.

There are believed to be about 10 launchers deployed in northern India, including the 335th Missile Battalion. The missiles are likely aimed at military targets in western, central and southern China. Although the Agni-II appears to have suffered from technical problems during its early operational service and failed several previous test launches, later successful tests in 2018 and 2019 indicate that the technical problems may have since been resolved.

Agni-III, a two-stage solid propellant mobile medium-range ballistic missile, can deliver a nuclear warhead over 3 kilometers. In 200, the Indian Ministry of Defense stated that the Agni-III was “in the arsenal of the armed forces” (Ministry of Defense 2014), and the Strategic Forces Command conducted a fifth test on November 2014, 30, launched from a test site on Abdul Kalam Island, the target area was on Abdul Kalam Island, East Coast of India.

The Agni-III MRBM failed its first night test, which was considered a "very important" test: the missile fell into the sea after the separation of the first stage. Since the test failure in 2019, no test firings of Agni-III have been publicly reported.

Agni-III deployment is still in its early stages; Fewer than 10 launchers are likely deployed and full operational status is unknown. The longer range potentially allows India to deploy Agni-III units further from the borders of Pakistan and China.

More than a decade ago, when the missile was still under development, an Army spokesman noted:

(India Today, 2008) - although this would require the Agni-III to be launched from the north-eastern part of India. From this region, the Agni-III IRBM will for the first time make it possible to keep the capital of China, Beijing, at gunpoint.

India is also developing the Agni-IV missile, a two-stage solid-fuel mobile medium-range ballistic missile capable of delivering a single-unit nuclear warhead to a range of over 3 kilometers, with the Ministry of Defense citing a range of 500 kilometers (Ministry of Defense, 4). After the final series of tests in 000, the MoD announced that Agni-IV would “begin serial production soon.”

Since then, the Strategic Forces Command has conducted three test launches, the last of which took place in December 2018, but the missile is not yet fully operational.

The Agni-IV MRBM will be capable of hitting targets throughout almost the entire territory of China, right up to Beijing and Shanghai. India is also developing a longer-range Agni-V MRBM - a three-stage solid-fuel mobile-based one. An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) of limited intercontinental range, capable of delivering a nuclear warhead over a distance of more than 5 kilometers. The increased range will allow the Indian military to establish Agni-V missile bases in central and southern India, further from the Chinese border.

In total, Agni-V underwent successful flight tests for eight launches, with the last test launch taking place in October 2021. The 2021 test was the first time the production Agni-V has been tested by combat crews, and more testing is likely to be required before the missile enters service.

The Agni-V missile brings important new capabilities to the Indian strike force. Unlike India's current ground-launched ballistic missiles, the Agni-V is placed on a launcher in a sealed container. The first two test launches were carried out from a railway launcher, but since 2015 all launches have been carried out from an automobile mobile launcher.

The TCT-5 launcher is a 140-ton, 30-meter, 7-axle transporter towed by a 3-axle Volvo truck. The container launcher design “will significantly reduce reaction time. Just a few minutes from stop to start,” said the former head of the Indian Defense Research and Development Organization in 2013 (Times of India 2013).

In June and December 2021, India test-fired its new two-stage solid-fuel medium-range ballistic missile, Agni-P, which the Indian government calls a “new generation” ballistic missile capable of carrying nuclear weapons (Government of India 2021c). Agni-P is India's first shorter-range ballistic missile, incorporating more advanced rocket motors, fuel, electronic components and navigation systems used in India's new longer-range missiles such as Agni-IV and Agni-V. .

One senior DRDO official observed during the early stages of Agni-P development:

Such statements are coupled with a clear improvement in the capabilities of the Agni-P compared to the earlier Agni-I and Agni-II missiles, which use older and less reliable solid fuels, hydraulic drives, and less accurate systems guidance, suggest that Agni-P will eventually replace these older missiles once they become operational.

India is also developing a conventional ballistic missile known as Pralay. Pralay was last tested in December 2021 and is said to be intended to take over the traditional role currently occupied by the Prithvi-II and Agni-I dual-use ballistic missiles.

Separating nuclear and short-range conventional strikes between the new Agni-P and Pralay missiles, respectively, could help reduce the risk of miscommunication during a conflict. This could be helped by the fact that the new Agni-P missile is likely to be operated by the Strategic Forces Command, which is responsible for India's nuclear arsenal, while the Pralay will be used by the Indian Army Ordnance Corps.

According to rumors, during the test of the Indian Agni-P missile in June 2021, two maneuverable decoys were used, simulating a payload equipped with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV); however, this information has not been confirmed by the Indian Ministry of Defense.

Similarly, press reports surrounding the Agni-V test in October 2021 claimed that the missile could be equipped with a MIRV. However, there are good reasons to doubt that India will add MIRVs to its missiles any time soon. There are no official reports that the Indian government has approved the MIRV development program, and loading multiple warheads on the Agni-V will reduce its range, which is a key goal of the missile's development in the first place.

The Agni-V is estimated to be capable of delivering a payload of 1,5 tons (the same as the Agni-III and Agni-IV), and India's first and second generation warheads, even modified versions, are considered relatively heavy. It took the Soviet Union and the United States hundreds of nuclear tests and 25 years of continuous effort to develop nuclear weapons small enough to equip a MIRV ballistic missile.

Moreover, the deployment of missiles with multiple warheads will raise questions about the credibility of India's minimum deterrence doctrine. The use of MIRVs would reflect a strategy of quickly hitting multiple targets and would also pose the risk of triggering a nuclear arms race with neighbors Pakistan and China.

However, it is likely that China's recent decision to equip some of its intercontinental ballistic missiles with MIRVs and Pakistan's announcement in January 2017 that it had test-fired the new Ababil medium-range ballistic missile with MIRVs could strengthen the position of India's defense industry. complex, which advocates the development of MIRV capabilities, if for no other reason than to avoid falling behind Pakistan in the development of MIRV technologies.

While Defense Ministry officials said several years ago that India's strategic missile force "will be limited to the Agni-V for now, with no successor or next series on the horizon or even on the drawing board", India has also apparently begun development of a full-fledged ICBM. known as Agni-VI.

Official details are sparse, but an article published on the government press information bureau website in December 2016 claimed that the Agni "will have a launch range of 8–000 kilometers" and "will be capable of being launched from submarines, and also from sushi.” How accurate these claims are is unknown, as a range increase of approximately 10 to 000 percent over the Agni-V seems unlikely.

India is also working on an anti-satellite interceptor.

In March 2019, the Defense Research and Development Organization completed its first successful anti-satellite test, called Mission Shakti, by shooting down one of its own satellites. According to the Indian Ministry of Defense, the interceptor was a three-stage missile with two solid rocket boosters, derived from an indigenous missile defense program (Ministry of Defense 2019, 96).

The destruction of the satellite created a large debris field consisting of hundreds of fragments, and while most of it re-entered Earth's atmosphere and burned up in the atmosphere, dozens were thrown into a higher orbit by the impact. Unidentified Indian military sources have also suggested that the interceptor will likely use the same propulsion system as the Agni-V ballistic missile.

Sea-launched ballistic missiles

India's arsenal consists of a ship- and submarine-launched ballistic missile carrying a nuclear warhead, a boosted implosion-type nuclear warhead containing a 4 kg plutonium core with a yield of 12 kt, and is developing a more advanced submarine-launched ballistic missile for possible deployment on submarines.

The ship-based ballistic missile "Dhanush" is a single-stage liquid-fuel short-range ballistic missile (400 kilometers), designed to be launched from the stern of two specially trained Sukanya class patrol ships (Subhadra and Sukanya). Each ship can carry two missiles. "Dhanush" is a ship version of "Prithvi-II".

The Dhanush missile has not been tested since February 2018, and its usefulness as a strategic deterrent weapon is severely limited due to its relatively short range; ships armed with the missile would have to sail dangerously close to the coasts of Pakistan or China to strike targets in those countries, leaving them vulnerable to counterattacks. Both ships are based at Karwar Naval Station on the west coast of India. The Dhanush will be decommissioned once one or two Arihant-class nuclear submarines become fully operational.

India's first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN), INS Arihant, was commissioned in August 2016, but spent much of 2017 and the first half of 2018 under repairs after its propulsion system was damaged. In November 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that Arihant had completed its first containment patrol, officially marking the completion of India's nuclear triad. He also said the deployment represented "a fitting response to those involved in nuclear blackmail."

The "containment patrol" lasted about 20 days; however, it is unclear whether the boat was actually equipped with nuclear weapons. The Arihant is very similar in design to the Russian-built Kilo-class attack submarines in service with the Indian Navy, except for a unique missile bay designed to accommodate Indian submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

Although INS Arihant conducted two underwater tests of the K-2018 missile in August 15, sources indicate that it will primarily serve as a training vessel and technology demonstrator and will not be used for "nuclear deterrence" patrols as more SSBNs arrive. These claims are further strengthened by the fact that the Arihant has been rarely seen, photographed or written about in recent years, despite the SSBN being a significant technological achievement for the Indian Navy.

The second SSBN INS Arigat (previously supposed to be called Aridhaman) was launched on November 19, 2017 and was commissioned into the Indian Navy in 2020, however, sea trials of the Arigat began only in early 2022, and as of May 2022 no there was no announcement confirming the boat's entry into service, indicating that the boat's entry into service was likely delayed.

Arigat will be followed by two more SSBNs, which are scheduled to enter service before 2024; however, it is likely that these boats will also be detained. The first of them, code-named S4, was launched in November 2021 and is noticeably longer and wider than the first two Indian SSBNs. Satellite images show that the S4 is about 18 meters longer than the first two SSBNs and is equipped with eight missile launchers, twice as many as the Arihant and Arigat.

India also appears to be developing the next generation of SSBNs, the S-5 class. A series of tweets by the Vice President of India during his visit to the country's Naval Science and Technology Laboratory revealed some details about what this new class of submarines might look like (Vice President of India, 2019). Photos show the new submarines will be significantly larger than the current Arihant-class submarines and could have eight or more launch tubes.

Analysts suggest that this new class of submarines could enter service in the late 2020s, once all four Arihant-class boats are completed. The Varsha SSBN naval base is currently under construction near Rambilli on the east coast of India and will reportedly be located adjacent to a facility associated with the Bhabha Atomic Research Center, India's premier nuclear research institute, which is also associated with its nuclear research program. nuclear weapons. INS Varsha is undergoing extensive construction with numerous mountain tunnels, large piers and support structures.

To arm SSBNs, India has developed one sea-launched ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead and is working on another: the current K-15 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) (also known as Sagarika or B-05) with a range of about 700 kilometers and the promising K-4 SLBM of a heavier class with a launch range of about 3 kilometers.

The relatively short range of the K-15 will not allow SSBNs to target not only Islamabad. Despite entering service in the summer of 2018, the K-15 should be viewed primarily as a bridge program designed to develop technologies for future, more capable missiles.

The K-4, which is said to have similar characteristics to the Agni-III medium-range ballistic missile, has undergone six test launches, two of which took place within just five days of each other in January 2020, and is said to have “virtually ready" for mass production. Video footage of the K-4 SLBM launch shows that instead of the cold launch system typically used on most SLBMs, whereby the missile is ejected from the launch tube using a gas generator, the K-4 uses two small engines on the front of the missile to lift it several meters above the surface of the water before the first stage propulsion engine starts.

Rumors about the K-4 claim that it is highly accurate, achieving "near-zero circular error probability," according to the Defense Research and Development Organization, and one official has been reported as saying, "Our CEP calculations are much more complex than the Chinese missile." . However, such claims should probably be taken with a grain of salt.

With a range of 3 kilometers, the K-500 will be able to target the entire Pakistan and most of China from the northern Bay of Bengal. Each SSBN launch tube will be capable of carrying one K-4 or three K-4. As is typical with nuclear programs, there are rumors and speculation that each K-15 SLBM will be capable of carrying more than one warhead, but this seems unlikely. Each boat is capable of carrying 4 K-12 Sagarika SLBMs or 15 K-4 SLBMs.

In addition, senior Indian defense officials said the Defense Research and Development Organization is said to be planning to develop a 5-kilometer range SLBM that would match the land-based Agni-V design and would allow Indian submarines to be targeted across Asia, parts of Africa, Europe and the Indo-Pacific region, including the South China Sea. The missile will have the same K-series designation as two other SLBMs currently in development, and was initially expected to be tested sometime in 000, although no such launch has occurred as of May 2022.

Cruise missiles

India is developing the Nirbhay land-launched cruise missile.

The missile is similar in appearance to the American Tomahawk or the Pakistani Babur and can also be intended for deployment in the air and at sea. The Indian Ministry of Defense describes Nirbhay as “the first long-range subsonic cruise missile developed in India, with a range of 1 kilometers and capable of carrying warheads weighing up to 000 kilograms” (Ministry of Defense 300).

After a series of unsuccessful tests beginning in 2013, successful flight tests in November 2017 and April 2019 indicate that some technical problems have been resolved.

While there are many rumors that Nirbhay has dual potential, neither the Indian government nor the US intelligence community has publicly stated this.

The test of the Nirbhay cruise missile with an Indian-made propulsion system was scheduled for April 2020; however, the test was delayed until August 2021 and was a partial success as the engine operated stably but the rocket subsequently crashed.

In early 2020, the Defense Research and Development Organization confirmed that additional variants of the Nirbhay cruise missile, including submarine-launched and air-launched versions, are in the early stages of planning and development.

Information