Features of approaches to ship construction

Launching of HMS Cambridge

How long can a sailing ship last? The question is not an idle one, because, for example, on our God-saved 1/6 of the land, the ordinary reader is sure that “in England the ship served for 50 years, in Russia - 5 years“, and therefore global conclusions were made that Russia is not a maritime power, it does not need a fleet, it is even contraindicated, and in general, as Captain Blood said to Captain Lavasseur:

Where did this look come from? From uncritical reading of English sources the fleet. However, first things first.

Fleet and Parliament

And to start with the basics, we will have to travel back to the XNUMXth century, to the time of the “Merry King” Charles II Stuart. At that time, England was fighting for supremacy at sea with Holland, and life itself forced the islanders to somehow streamline their maritime policy.

Since the time of the father of the current monarch, Charles I, Parliament has arrogated to itself the prerogative of approving the construction of new ships (or refusing this undertaking). Since Charles I had a constant conflict with Parliament, and still wanted a fleet, he even went to direct violation of this rule by introducing a well-forgotten old tax - “ship money”, which went directly to the royal treasury, bypassing the treasury of Parliament. The House of Commons appealed to the Magna Carta, according to which any tax imposed without the consent of Parliament is illegal. It is clear that Parliament declared Karl’s initiative illegal, and all contractors began to refuse the tax one after another. As a result, by the 1640s, a revolutionary situation had developed in the kingdom, and then the English Revolution began.

In 1660, Charles II came to power, but the problem of building a fleet remained. For example, in 1677, during a debate in Parliament regarding the building program "thirty ships“The Admiralty came out with a request to allocate 1,6 million pounds for the fleet, to which parliamentarians simply stood on their hind legs. As one of the deputies said:

Samuel Pepys

Admirals and members of the Fleet Council were simply infuriated by the constant discussion in Parliament of issues of financing the fleet. In addition, Secretary of the Admiralty Samuel Pepys insisted that some kind of systematization was needed in the construction of the fleet. For example, if we have 100 ships, and each ship serves for 10 years, then it is clear that we need to lay down 10 ships every year in order to maintain the number of ships at the proper level.

With the same level of administration that existed in the 1660s and 1670s, the fleet was either showered with golden rain or choked by financial drought.

And in 1686 Pepys found a way out. According to Bryant's book "Samuel Pepys: Savior of the Fleet", Pepys found an ingenious legal solution - now the rebuilding and timbering of ships was carried out as a permanent expense for the Admiralty, while the construction of new ships was necessarily approved by Parliament. That is, Parliament allocates money for repairs without discussion or debate.

Since coordination with Parliament was a long and tedious matter, in 1686 the number of ships was fixed, within which it was possible to carry out light and major repairs, and this number was fixed at around 100 ships.

According to Davis's book Pepys's Fleet: Ships, Men and Battles, 1649-1689, in 1688 Pepys took advantage of the innovation to "to repair“(in fact, build anew) 69 Royal Nevi ships, which puzzled parliamentarians a little - they say, did we resolve everything correctly? And as a result, the following agreement was reached - the timber hulls of the ships were divided into upper (repair) and deep (rebuild). There were restrictions on the number of the latter per year.

What is timber?

What was meant in the English fleet (not always, but quite often) by deep timbering (rebuild)? Let’s say that the conventional battleship “Monсk” has fallen into disrepair, and in theory it should be scrapped and a new ship built. But! The construction of a new ship, as we remember, is coordinated with Parliament, which we absolutely do not want to do. As a result, the “Monсk” is brought into some Sheerness for disassembly, the damaged parts are thrown out, the good ones are stored, and at this time in the conditional Chatham, an actually new ship is being built, where parts of the old ship are used (and sometimes not used), but the ship is still it is also called “Monсk”, and its service is continuous.

Do you think this is a joke? Absolutely not. For example, the already mentioned 52-gun “Monck” built in 1659 in 1677 was timbered, as a result of which its length was increased from 32 to 42 meters along the keel, its width from 10 to 11 meters, and it itself became 60-gun.

In 1702, another deep restructuring was carried out, and the ship was scrapped only in 1720. That is, we see that as a result of the repair a completely new ship appeared, but anyone who reads the sources uncritically will tell us that HMS Monck served for 50 years, although these 50 years actually fell on three different ships.

Chatham Dockyard in the XNUMXth century

Nevertheless, Pepys's innovation was a giant leap forward - now the size of the Royal Navy's ship's personnel was legally fixed, and it was possible to form a permanent maritime budget.

Real life times

So how long did English ships actually serve?

The Correspondence of the Honorable John Sinclair (1842), page 242, gives the following data on the service life of oak in shipbuilding:

Russian Kazan oak – 10 years.

French oak – 15 years.

Polish oak – 15 years.

German oak – 15 years.

Danish oak – 20 years.

Swedish oak – 20 years.

English oak – 25 years.

The best English oak is 40-50 years old.

And here is the Westminster Review, volume 6 for 1826. There, on pages 129 and 130, is a report by the British and Colonial Forestry Commissioners, according to which the average life expectancy of ships built for the Royal Navy from 1760 to 1788 was 11 years and 9 months.

There, just below, is a report for Parliament made by the Third Lord of the Admiralty, Robert Sappings, according to which the service life of a ship, depending on the wood, ranges from 3 to 9 years.

Comparison of ships built from colonial wood with ships built from Baltic wood (by this we mean, first of all, Polish and German oak; on the colonial side, here is Canadian oak and Canadian pine):

HMS Cydnus – 3 years 2 months.

HMS Eurotas – 3 years 8 months.

HMS Nigeria - 3 years.

HMS Meander - 3 years 4 months.

HMS Pactolus – 3 years 11 months.

HMS Tiber – 4 years 10 months.

HMS Araxes - 2 years 8 months.

Average service life – 3 years 6 months.

Baltic wood:

HMS Maidestone - 8 years 11 months.

HMS Clyde - 8 years 6 months.

HMS Circle – 8 years 11 months.

HMS Hebe – 6 years 6 months.

HMS Jason - 9 years 11 months.

HMS Minevra - 8 years 6 months.

HMS Alexandria - 7 years 10 months.

Average service life is 8 years 3 months.

HMS St Albans launched

In the same note, Seppings, commenting on his data, proposes that in order to adjust timber reserves from Canada, we should approximately accept the data that the service life of a ship made of Canadian wood is equal to half the service life of a ship made of Baltic wood.

In the 1830s, the service life of oak ships increased to 13 years.

Some conclusions

First of all, let's note that no oak ship, even the best one, can withstand 50 years without repairs. The whole question is the price and labor intensity of this repair. As an example, HMS Victory, Admiral Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar, was built in 1765 at a cost of £63. But the amount of its repairs amounted to 176 thousand pounds, that is, 215 times more than the cost of the ship itself.

Logic dictates that it would be much easier to break down a ship that has fallen into disrepair and build a new one. But... we remember about coordination with Parliament. Besides, there was another reason. In England, already in the XNUMXth century, the last oak forest was eliminated, and starting from the time of Charles II, the British were forced to import ship timber. In this situation, you have to be careful with what you already have, hence the constant repairs, timbering, rebuilding, etc. This at every stage made it possible to at least somehow save on the purchase of wood in third-party countries.

But is such a system an example to follow?

I’ll say a seditious thought - such a system was not needed anywhere except... England, with its parliamentary troubles.

In ordinary countries, these legal tricks would not make sense; everything would be determined by the availability of money and the need for a fleet at a particular moment. Let us take as an example a country that was not particularly good at building a fleet - the early USA. As soon as the war - Congress allocates money for the construction of the fleet, while the fleet is being built - the war is over, and unfinished ships can stand, gradually rot and collapse on the stocks for decades.

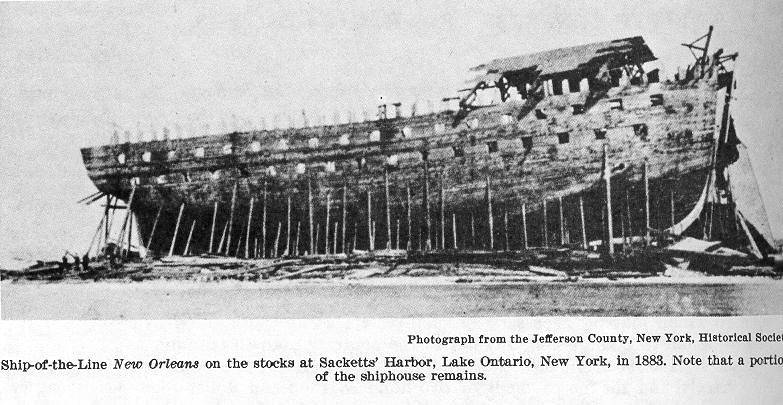

USS New Orleans, construction of which began in 1814. Photo from 1883

Here's another example. Throughout the 25th century, Denmark pursued a consistent maritime policy and was always concerned about having 28-XNUMX battleships at hand; They introduced both an accounting system and timely replenishment of the number of personnel by the king himself, without any tricks. The cost of repairs and the cost of building a new ship were honestly considered, and what was more profitable was simply done. Without any legal hassles.

And what about Russia?

You and I remember that the original question contained the phrase “the ship served in England for 50 years, and in Russia for 5 years" What is the real service life of Russian ships?

If we take, for example, the array of Russian 50-gun ships built between 1712 and 1720, then on average each ship served for 8 years and 2 months. Yes, in the statistics there is the 50-gun Vyborg, which served for only 3 years (it crashed), but there are also the ships Riga and Rafail, which honestly served for 11 years.

If we take the Russian 80- and 90-gun Peter - then even if we take the service of the ship "Lesnoye" for one year (built in 1718, had an accident in 1719, was repaired by 1720), then the average service life of the Russians “heavyweights” will be 13 years and 4 months versus 17 years and 11 months before the first deep timber season for the British. If the Lesnoye accident is not taken into account, then the time frame will be quite comparable.

Another question is that Peter I did not need those very timber allowances as a fact, since Russia was a rude, non-parliamentary country, the tsar himself approved the spending. And he himself monitored the size of the fleet.

It is clear that all these comparisons are a little manipulative. For example, English ships sailed much more, and in different latitudes, in different seas and oceans. On the other hand, Russian ships froze into ice every winter, which did not contribute to the life expectancy of the ship, as everyone understands.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that with different approaches and different uses, the parties arrived at approximately the same service life.

The main problem of the Russian fleet was a completely different problem. Construction from substandard or unseasoned wood affected the quality of the construction. No, there were quite enough such ships for the Baltic. Problems began when the Russian fleet entered the seas and oceans. Already in the Archipelagic expeditions, big problems arose with the condition of the ships, and this was just a transition from the Baltic to the Mediterranean Sea along the coast.

At the same time, for those same Spaniards, whom all lovers of sea adventures love to make fun of, ocean crossings were not heroism, but a standard task, an everyday occurrence. That is, in Spain they treated the quality of construction much more strictly than in Russia.

Replica of the 52-gun ship "Poltava" at the naval parade in St. Petersburg

This is how a Spanish commission agent assessed the Russian ships in 1818, after carefully examining them:

In just a few sentences, the Spaniard quite clearly described the shortcomings of the “Russian approach” to the construction of ships. Yes, it's cheap. But it makes sense to build such ships when you are sailing close to the shore. Ocean voyages require a completely different quality of construction.

References:

1. JD Davies "Pepy's Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 1649-89" - Seaforth Publishing; 1st Edition edition, 2008

2. A. Bryant “Samuel Pepys; The Savior of the Navy" - The Reprint Society Ltd; Reprint edition, 1953.

3. Robert Greenhalgh Albion “Forests and sea power; the timber problem of the Royal Navy, 1652-1862", 1926.

4. Sir John Sinclair. "The Correspondence of the Right Honorable Sir John Sinclair, Bart. With Reminiscences of the Most Distinguished Characters Who Have Appeared in Great Britain, and in Foreign Countries, During the Last Fifty Years" - London: H. Colburn & R. Bentley, 1831.

5. "The Westminster Review", t.7, oct. 1826-jan. 1827 - Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1827.

6. Lyon D. “The Sailing Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy-Built, Purchased and Captured-1688–1860 (Conway's History of Sail)” - Conway Maritime Press, 1998.

7. “Sea Collection”, 1896, No. 3.

8. V.G. Andrienko. “Sale of the Russian squadron to Spain in 1817–1818” // Gangut: Sat. Art. - St. Petersburg, 2006. - Issue. 39.

9. On the state of the Russian fleet in 1824: from a manuscript found in incomplete form in the papers of Vice Admiral V.M. Golovnin / op. Midshipman Morekhodov [pseud.]. - St. Petersburg: type. Mor. m-va, 1861.

10. Barcos rusos para Fernando VII // Singladuras por la historia naval: https://singladuras.jimdofree.com

Information