Czech machine guns in the armed forces of Nazi Germany

Between the world wars, Czechoslovakia was one of the most developed countries in Europe. armory an industry that not only fully met the needs of the national armed forces, but also actively supplied its products for export. In the 1930s, Czech machine guns, which were put into service in a number of countries, enjoyed great success on the world market. Moreover, samples designed by Vaclav Holek were produced under license in the UK and China.

After the annexation of the Czech Republic, these machine guns were actively used by the armed forces of Nazi Germany and its allies. At the first stage, the production of Czech machine guns continued, but from the second half of the war, German-made weapons began to replace them in production.

Light machine guns

Soon after the formation of the army of Czechoslovakia, there was an urgent need for a light machine gun that could be used for fire support of an infantry squad, carried and serviced by one soldier.

The troops had a number of French Fusil-Mitrailleur Chauchat Mle 1915 light machine guns and Danish Madsen M1922 and M1923 light machine guns. However, these samples did not satisfy the military. The French "Shosha" was one of the most unsuccessful machine guns of the First World War, and the "Madsen" was quite complicated and time-consuming to manufacture, and it was considered unsuitable for production in Czechoslovakia.

In 1922, the Czechoslovak Defense Ministry announced a competition for a new light infantry machine gun. In 1926, the military chose the ZB-26 light machine gun (army designation vz. 26), designed by Vaclav Holek.

The magazine-fed ZB-26 with a top-mounted cartridge receiver was based on the Praga I.23 belt-fed machine gun that had not been accepted into service. Mass production of the ZB-26 began in 1928.

Machine gun ZB-26

The ZB-26 light machine gun has established itself as a reliable and unpretentious weapon. For firing from it, a German cartridge of 7,92 × 57 mm was used. The automatic machine gun functioned due to the removal of part of the powder gases from the bore. The barrel was locked by skewing the bolt in a vertical plane. The trigger mechanism allowed firing single shots and bursts. The barrel is quick-change, a handle is fixed on the barrel, which is designed to facilitate the process of replacing the barrel and carrying the machine gun. Shooting is carried out relying on a bipod, or from a light machine, which also had the ability to fire at air targets.

With a length of 1 mm, the mass of the ZB-165 without cartridges was 26 kg. Food was supplied from a 8,9-round box magazine inserted from above. The rate of fire is 20 rds / min, but, due to the use of a small-capacity magazine, the practical rate of fire did not exceed 600 rds / min.

In fairness, it must be said that the upper location of the receiving neck has both minuses and pluses. The disadvantage is the limited visibility when firing, but at the same time, such an arrangement speeds up loading and avoids clinging to the ground with the magazine body.

Machine gun ZB-30

The ZB-30 light machine gun was distinguished by the design of the eccentric that set the shutter in motion, and the firing pin actuation system. The weapon had a gas valve that allowed to regulate the flow of powder gases into the cylinder, and a tide for installing an anti-aircraft sight. The mass of the ZB-30 has increased to 9,1 kg, but it has become more reliable. Rate of fire: 500–550 rds/min.

After the occupation, the Germans had more than 7 ZB-000 and ZB-26 machine guns at their disposal. Czech light machine guns in the armed forces of the Third Reich received the designation MG.30 (t) and MG.26 (t).

For firing from German machine guns, K98k rifle cartridges were mainly used. The main cartridge was considered to be 7,92 × 57 mm sS Patrone, with a heavy pointed bullet weighing 12,8 g. In a 600 mm barrel, this bullet accelerated to 760 m / s. For lightly armored and air targets, the Germans widely used cartridges with SmK armor-piercing bullets. At a distance of 100 m, a bullet weighing 11,5 g with an initial velocity of 785 m/s could normally penetrate 10 mm armor. The ammunition load of infantry machine guns could also include cartridges with armor-piercing incendiary bullets PmK

The MG.26(t) and MG.30(t) light machine guns were mostly used by the German occupation, security and police units, as well as by the Waffen-SS formations. In total, the German armed forces received 31 Czech light machine guns. Such machine guns were also in service in Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia and Croatia.

Although the ZB-26 and ZB-30 lost in practical rate of fire to the German MG.34 and MG.42, Czech-made light machine guns had a simpler design and were lighter. A machine gun with a magazine for 20 rounds in terms of fire density could not compete with German machine guns that had belt feed, but a machine gunner who personally carried 6-8 magazines had the opportunity to act independently and dispense with the second number of the calculation, which significantly increased mobility and flexibility of use.

The refusal of their production at the Waffenfabrik Brünn enterprise (renamed Zbrojovka Brno) in 1942 was not associated with the shortcomings of weapons, but with the desire of the German command to unify machine gun armament, which, however, failed. One way or another, the ZB-26 and ZB-30 machine guns, as well as their foreign clones, were used by the warring parties until the end of World War II, and in some countries they are still in service.

In 1942, the production of German belt-fed MG.42 machine guns began in Brno. The MG.34 and MG.42 machine guns had a very high rate of fire and are considered the first mass-produced single machine guns. The work of their automation is based on a short stroke of the barrel with the shutter locked by rollers with breeding to the sides. The problem of barrel overheating during prolonged shooting was solved by replacing it. The barrel was supposed to be changed every 250-300 shots. For this, the kit included two or three spare barrels and an asbestos glove. During offensive operations, these machine guns mainly fired from bipods. In a stationary position in defense, they were often mounted on a machine.

MG.42 machine gun

The MG.42 machine gun had a length of 1 mm. Weight without cartridges - 200 kg. Depending on the mass of the shutter, the rate of fire was 11,57–1 rds / min. The MG.000 differed from the MG.1 in lower cost and was better adapted to mass production. In the manufacture of the MG.500, stamping and spot welding were widely used. In order to simplify, they abandoned the possibility of feeding the tape from either side of the weapon, store food and the fire mode switch.

The production of machine guns under the German order in the Czech Republic continued until the end of April 1945. In the first post-war decade, MG.42 machine guns, along with other weapons chambered for 7,92 × 57 mm, were in service with the Czechoslovak army.

Machine guns

As a legacy from Austria-Hungary, the armed forces of Czechoslovakia inherited several thousand machine guns Maschinengewehr Patent Schwarzlose M.07 / 12, Škoda M1909 and M1913.

Machine gun Škoda M1909

The Škoda M1909 and M1913 machine guns quickly disappeared from the scene, and the much more successful Schwarzlose machine guns were modernized and remained in service until the annexation of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany.

The water-cooled Schwarzlose machine gun, which used the 8×50 mm R Mannlicher cartridge, had a semi-free bolt locking system, which simplified the design and reduced the cost. However, for reliable operation of automation, the machine gun barrel had to be shortened to 66 calibers (530 mm) at a time when other easel machine guns had a barrel length of 90-100 calibers. In this regard, the initial speed of the bullet that left the shortened barrel was relatively low, which adversely affected the accuracy of shooting at medium and long distances.

In the early 1920s, the Schwarzlose machine gun was modernized under the guidance of engineer Frantisek Janecek. The converted heavy machine gun received a 630 mm barrel extended to 7,92 mm, a modified bolt and a modified cartridge supply system. Modernized machine guns had the designation vz. 7/24, newly made - vz. 24. In total, about 8 machine guns were modernized and manufactured.

Machine gun vz.7/24

According to the characteristics of the easel machine gun vz. 24 was a solid middle peasant among his peers. The body weight of the machine gun without coolant was 19,3 kg. Together with a tripod machine - 40,3 kg. The initial speed of the bullet is 755 m / s. Rate of fire - 520 rds / min. Belt capacity - 250 rounds. Calculation - 3 people.

In the mid-1930s, the vz. 24 was considered obsolete, and it was planned to replace it with a new, much lighter and faster-firing machine gun ZB-53. However, a water-cooled machine gun could still be quite effective when it was not necessary to change the firing position frequently. In this connection, machine guns vz. 24 were transferred to the border fortified areas, where they were used in long-term fortifications.

At the end of 1938, the Czechoslovak army had 7 vz. 141/7 and vz. 24. Subsequently, the Germans mainly placed them in the fortifications of the Atlantic Wall, but several hundred of these machine guns hit the Eastern Front. They were also in the Slovak formations that fought on the side of the Nazis.

One of the best heavy machine guns of World War II is considered to be the ZB-53, the designer of which was Vaclav Holek. Like other Czechoslovakian weapons of the interwar period, it used the 7,92x57mm cartridge. Officially, the ZB-53 entered service in 1937 and had the army designation vz. 37.

Machine gun ZB-53

The automatics of the ZB-53 machine gun worked by removing part of the powder gases through a side hole in the barrel wall. The barrel bore is locked by tilting the bolt in the vertical plane. In case of overheating, the barrel could be replaced. The mass of the machine gun with the machine was 39,6 kg, length - 1 mm. There was a rate of fire switch from 096 to 500 rds / min. A high rate of fire was necessary when firing at aircraft. For anti-aircraft fire, the machine gun was attached to the swivel of the folding sliding rack of the machine.

Due to the relatively small weight for a heavy machine gun, high quality workmanship, good reliability and high accuracy of firing, the ZB-53 was popular among the troops.

In the armed forces of Nazi Germany, the ZB-53 was called MG.37 (t). In addition to the Wehrmacht and the SS troops, the Czech machine gun was widely used in the armies of Slovakia and Romania. In total, representatives of the German Ministry of Armaments accepted 12 Czech-made machine guns. Unlike other foreign-made machine guns, which were used mainly in the rear and police units, the MG 672 (t) machine guns were very actively used on the Eastern Front.

The German command as a whole was satisfied with the characteristics of the machine gun, but according to the results of combat use, they wanted to have a lighter and cheaper model, and when firing at air targets, increase the rate to 1 rds / min. The specialists of the Zbrojovka Brno enterprise, in accordance with these requirements, created several prototypes, but after the cessation of production of the ZB-350 in 53, its improvement was stopped. The formal reasons for ending the production of the ZB-1944 are the complexity of manufacturing, metal consumption and high cost. However, the main reason for the transition of the weapons factory in Brno to the production of MG.53, apparently, is still the desire of the German command to reduce the variety of machine guns, at least in the units directly involved in the hostilities.

Aviation, anti-aircraft and heavy machine guns

Before the Second World War, the Czechoslovak industry produced the entire range of weapons necessary to equip the national army: individual and group small arms, artillery, transport and armored vehicles, Tanks and combat aircraft.

For aviation in Czechoslovakia, a machine gun of rifle caliber vz. 30 (CZKvz.30). As the designation suggests, it was put into service in 1930. When creating an aircraft machine gun vz. 30, the inspiration for the design team led by Frantisek Mouse was the British Vickers Mk.III. The Czechs had experience in operating the Vickers aircraft and evaluated it positively. In the 1920s, Czechoslovakia acquired several hundred British-made aircraft machine guns. The fighters used fixed belt-fed Vickers Class Fs, while the defensive turrets used disk-fed Lewis machine guns.

Although Czechoslovakia acquired a license to manufacture the Vickers Mk.III, and it was produced under the designation vz. 28, the military wanted to get a single aircraft machine gun suitable for use in offensive and defensive installations. For this, the details of the Vickers Mk.III receiver have been significantly redesigned.

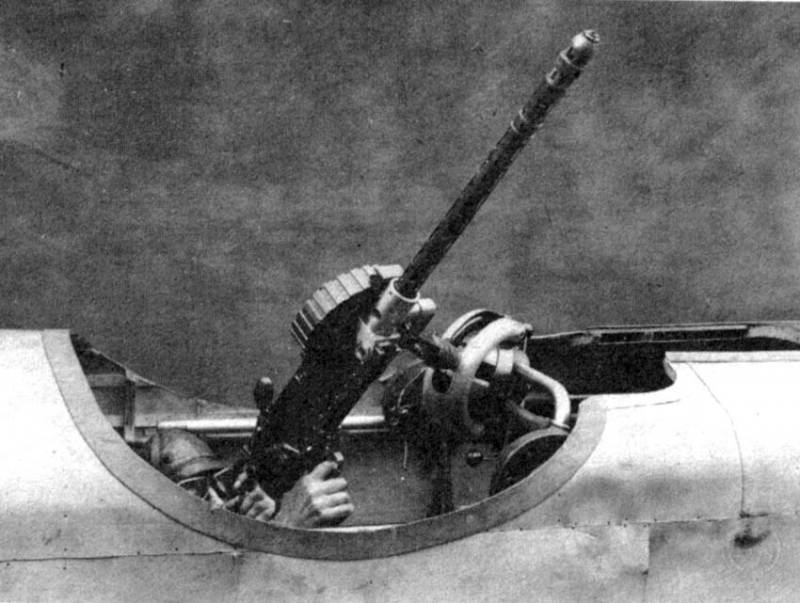

On the Czechoslovak aviation machine gun vz. 30, it was possible to change the power scheme from tape to magazine, which used a disk magazine with a capacity of 50 rounds. An easily dismantled pistol grip with a trigger was attached to the bottom of the bolt carrier, in the back there was an easily removable folding shoulder rest.

Aviation machine gun vz. thirty

As on the British Vickers Mk.III, vz. 30 worked due to the short stroke of the barrel during recoil. Depending on the version, the weight of the machine gun was 11,4–11,95 kg. Length - 1 mm. Barrel length - 033 mm. The rate of fire with magazine feed was 720 rds / min, with tape - 950 rds / min. The ammunition, in addition to the usual ones, included tracer and armor-piercing incendiary bullets weighing 1–100 g.

Release of machine guns vz. 30 deployed at the state arms factory in Strakonice (Česká zbrojovka Strakonice). Until 1938, about 4,5 thousand of these machine guns were assembled at the plant, which were used in Czechoslovakia and were exported. In particular, the vz.30 batch was sold to Greece. Given the higher rate of fire than that of infantry models, some of the aircraft machine guns were used in ground-based anti-aircraft installations, which were intended to provide air defense for airfields.

The new owners converted the Czech machine guns that the Germans got for the most part into anti-aircraft guns, and many of them ended up on the Eastern Front.

In the middle of the war, the arms industry of the Third Reich no longer had time to compensate for losses in the east, and there was a shortage of machine guns in the troops.

The war of attrition led to the fact that frankly outdated weapons were withdrawn from the warehouses and they were forced to use various ersatz samples, including aviation machine guns mounted on bipods converted for use in infantry.

In the mid-1930s, due to the increase in flight speed and the security of combat aircraft, the design bureau of the Zbrojovka Brno enterprise began to create a heavy machine gun that could also fight light armored vehicles.

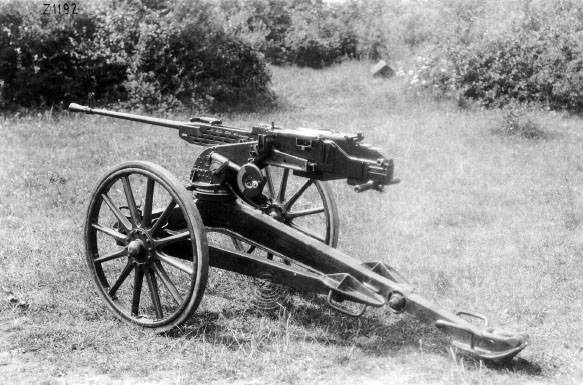

Shortly before the dismemberment and occupation of Czechoslovakia, a large-caliber 15-mm machine gun ZB-60 was adopted. Small-scale production of these machine guns at the Škoda enterprise began in 1937.

15 mm machine gun ZB-60 in transport position

The design and operation of the automation of the 15 mm machine gun had much in common with the 7,92 mm ZB-53 machine gun, but the rate of fire was significantly lower - 420-430 rds / min. For firing, the ZB-60 used a 25-round belt, which limited its practical rate of fire. The body weight of the ZB-60 machine gun without a machine tool and ammunition is about 60 kg. The total mass of weapons on a universal machine exceeded 100 kg. Length - 2 mm. The original cartridge 020×15 mm with a muzzle energy of about 104 kJ was used for firing. The muzzle velocity of a bullet weighing 31 g was 75 m/s, which ensured a long range of a direct shot and excellent armor penetration. The ZB-895 ammunition could include cartridges: with ordinary, armor-piercing and explosive bullets.

Czech military officials could not decide for a long time whether they needed this weapon. The decision to mass-produce 15-mm machine guns after repeated tests and improvements was made only in August 1938. Before the German occupation, only a few dozen 15-mm machine guns were produced for their own needs. No more than a hundred ZB-60s were assembled until 1941 at the Škoda enterprise, which, under German control, became known as Hermann-Göring-Werke.

Subsequently, the Germans also captured a number of British 15 mm BESA machine guns, which were a licensed version of the ZB-60. Due to the limited amount of ammunition for captured 15-mm machine guns, during the Second World War, the production of 15-mm cartridges was launched at German-controlled enterprises. In this case, the same bullets were used as for the MG.151 / 15 aircraft machine guns. This approach made it possible, thanks to partial unification, to reduce costs in the production of ammunition. Since these German 15 mm bullets had a leading belt, they were structurally artillery shells.

When firing from a regular tripod-wheel machine, the accuracy of the 15-mm machine gun left much to be desired. Acceptable accuracy had the first 2-3 shots. In this regard, the Germans often mounted the captured ZB-60 and BESA machine guns on massive pedestals, and in stationary use they mounted them on a log dug into the ground.

15-mm machine guns had parts of the SS, anti-aircraft gunners of the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine. In German documents, this weapon was called MG.38(t). The refusal to continue production of the ZB-60 was explained by their high cost and the desire to free up production capacity for weapons developed by German designers.

The ZB-60 had a very high potential and was comparable in its characteristics to the Soviet 14,5 mm KPV machine gun, which was put into service after the war. But due to the high saturation of the German army with 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, the high cost and complexity of production, they refused to modernize and further produce 15-mm machine guns.

Продолжение следует ...

Information