Electronic warfare. Battle of the Atlantic. Ending

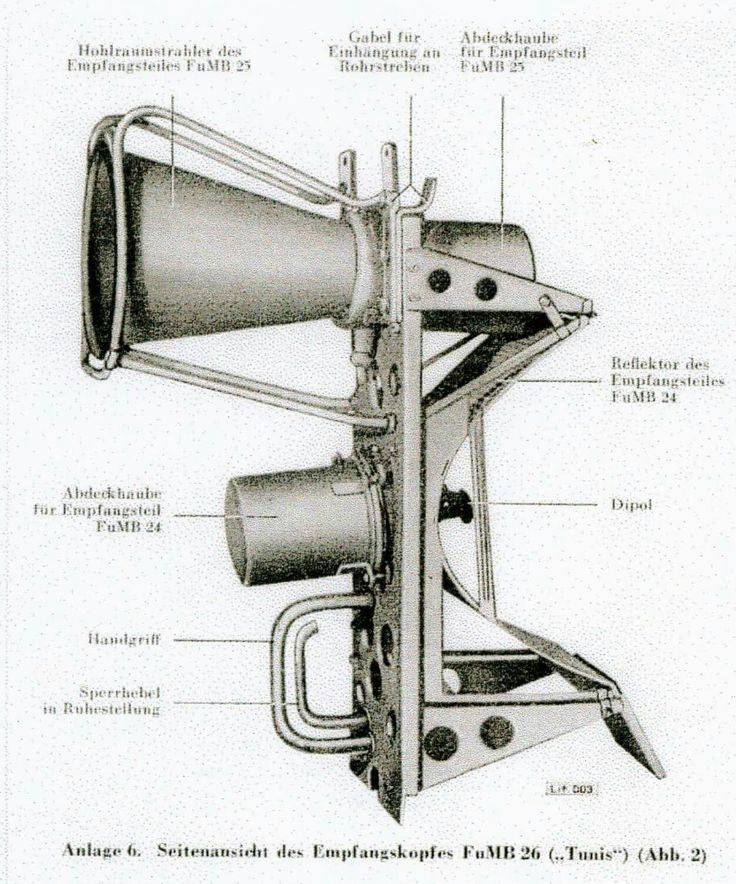

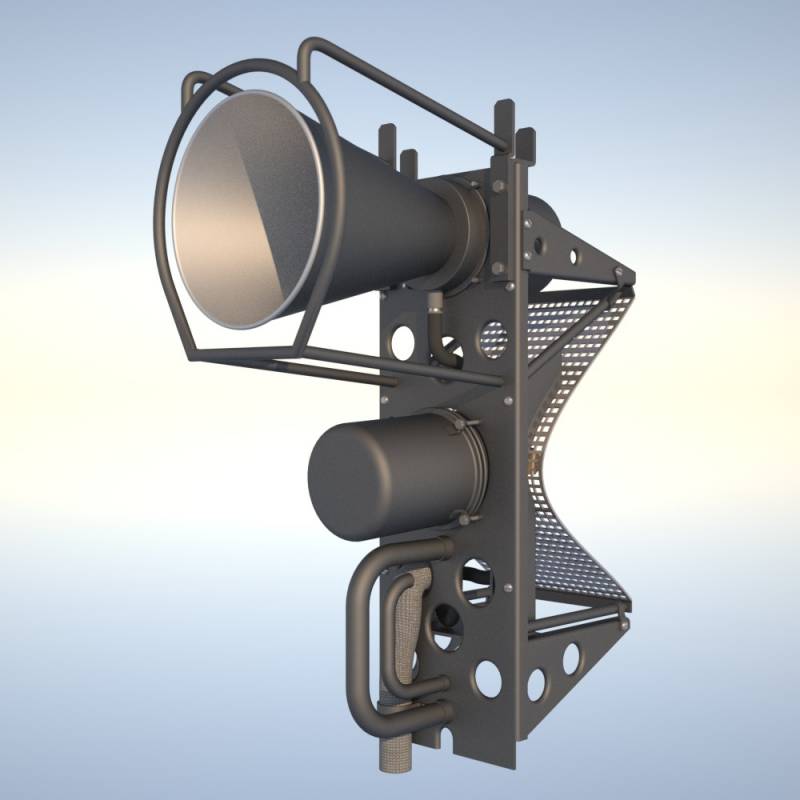

In the fight with enemy surface ships, German submariners used centimeter radar in low visibility conditions. At the same time, for fixing enemy radio emission at the beginning of 1944, the submarine had a FuMB 26 Tunis radio receiver, which was a combined system that included the FuMB 9 Mücke 24-centimeter FuMB 3 Fliege and 25-cm.

Radio FuMB 26 Tunis

Its effectiveness was quite high - Tunis "saw" the radar of the enemy at a distance of 50 km, in particular 3-cm, the English DIA Mk.VII radar. "Tunisia" was the result of a thorough examination by the Germans of the wreckage of a British aircraft shot down over Berlin, equipped with an 3-centimeter radar. Funny stories Happened to American reconnaissance aircraft that wandered across the Atlantic in search of radio waves krigsmarine. By the end of the war, they almost ceased to fix the radiation - it turned out that the Germans were so scared by the enemy’s response that they simply stopped using radars.

One of the copies of the British aviation Radar station in the museum

Among the retaliatory tricks of the German fleet were imitators of surface targets, called Aphrodite and Tetis. Aphrodite (according to other sources, Bold) was mentioned in the first part of the cycle and consisted of hydrogen-filled balls with aluminum reflectors that were attached to a massive float. Tetis was even simpler - a rubber bottle supporting reflectors coated with aluminum foil. And this primitive technique turned out to be quite effective. American planes with the British found them at the same distance as real targets, and the signature of the traps did not give out anything. Even the most experienced radar operators could not confidently distinguish Aphrodite and Tetis from German ships.

The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen in the hands of the Americans

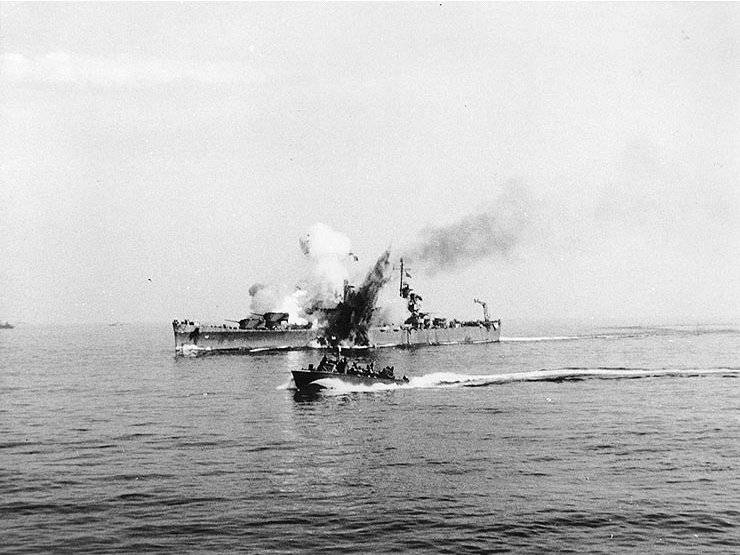

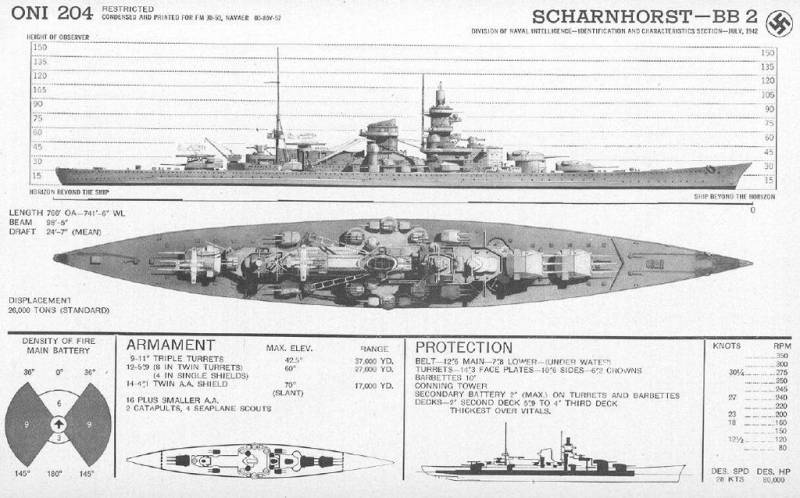

Despite some backwardness in matters of EW, the Germans still had something to be proud of. On the night of February 12, 1942 was actively hampered by British locators on the south coast of England, thanks to which the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen together with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau battleships managed to slip through the English channel almost unnoticed. The ships themselves should have been at maximum speed to escape from the French Brest, while all radar instruments on them were turned off. All the work of jamming the British was done by the Breslau II - a coastal transmitter on the French coast and three He 111H. The latter were equipped with Garmisch-Partenkirchen imitation jamming transmitters, which created phantoms of the approaching large bomber formations on the English locators. In addition, a special squadron was formed, which specifically plied around the British Isles, further diverting attention. And such harmonious integrated work of the Germans was crowned with success - later the British newspapers wrote bitterly that "since the seventeenth century the royal fleet has not experienced anything more shameful in its waters." The most interesting is that the British could not identify the electronic attack on their locators. Until the very last moment, they believed that they had encountered malfunctions. On the Germans side there was a dark night and thick fog, but still they were discovered, but not by locators, but by patrol aircraft. Prinz Eugen, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau even managed to fall under the shelling of the coastal battery of the British, who worked on ships of all pairs from 26 km distance. The battle for the breaking through ships were conducted both in the air and by the artillerymen of the coastal batteries on both sides of the English Channel. Scharnhorst, barely able to fend off annoying torpedo boats, ran into a mine and rose, risking becoming a simple target for British bombers. The British attacked 240 bombers, who in a desperate attempt to drown the fugitives. But the sailors of Scharnhorst quickly eliminated the damage, and under the cover of the Luftwaffe, the battleship continued to move. Gneisenau later also distinguished himself with a meeting with a mine, which, however, did not bring anything significant, and the ship continued to move.

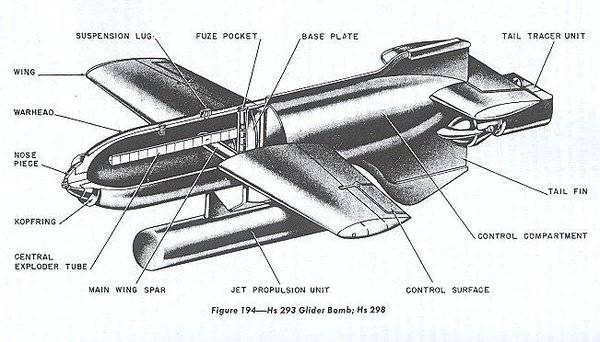

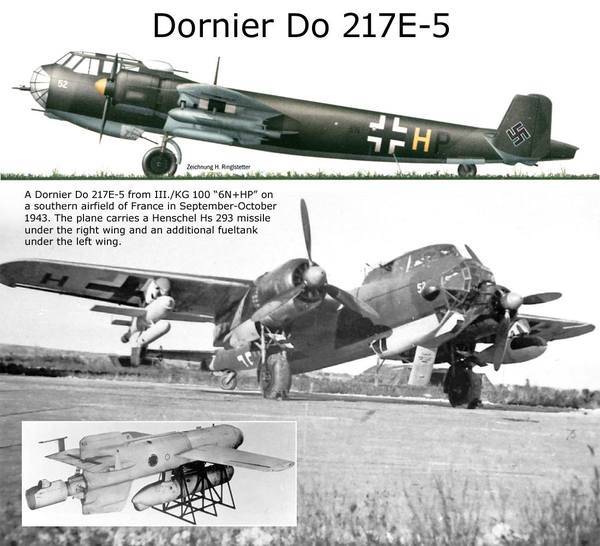

Planning UAB Fritz X

The allies had to fight with one more unexpected misfortune from the German side - guided weapons. In the middle of the war, the fascists had Herschel Hs 293A guided bombs and planning guided bombs like the Fritz X. The operating principle of the new products was quite simple by modern standards - the Kehl radio transmitter on the plane and the Strassburg receiver on ammunition were the core of this system. The radio command system worked in the meter range, and the operator could choose between 18 operating frequencies. The first attempt to “silence” such weapons became the jammer XCJ-1, which appeared on the American destroyers involved in escort escorts at the beginning of 1944. Not everything went smoothly with XCJ-1 with the suppression of massive attacks of guided bombs, as the operator had to tune to a strictly defined frequency of a single bomb. At this time, the remaining Herschel Hs 293A and Fritz X operating at different frequencies successfully hit the ship. I had to turn to the British, who at that time were the undisputed favorites in the EW. The English 650 type jammer worked directly with the Strassburg receiver, blocking its connection at the 3 MHz activation frequency, which prevented the German operator from selecting the radio control channel. The Americans, following the British, improved their transmitters to XCJ-2 and XCJ-3, while Canadians had a similar Naval Jammer. As usual, such a breakthrough was not accidental - the German Heinkel He 177, which was equipped with a control system for new bombs, fell on Corsica in advance. Careful study of the equipment and gave the Allies all the trump cards.

An example of a successful guided bomb hit in the Allied ship

AN / ARQ-8 Dinamate from the United States generally allowed to intercept the management of German bombs and remove them from escorts. All these measures forced the Germans to abandon the use of radio-controlled bombs by the summer of 1944. Hope gave the transition to control by wire at Fritz X, but in these cases, the goal had to get too close, which eliminated all the advantages of planning bombs.

The standoff in the Atlantic was an important, but by no means the only example of successful use or disastrous neglect of EW capabilities. The Germans, in particular, had to frantically resist the armadas of Allied Air Force bombers, who at the end of the war leveled the country to the ground. And the fight on the radio front played here not the last value.

Based on:

uboat.net

wiki.wargaming.net

Paly A.I. Radiovna. M., Military Publishing, 1963

Mario de Arcangel. Electronic warfare From Tsushima to Lebanon and the Falkland Islands. Blandford Press poole dorset, 1985

Pirumov V.S., Chervinsky R.A. Radio electronics in the war at sea. M .: Voenizdat, 1987

Electronic warfare. From past experiments to the decisive front of the future. Ed. N. A. Kolesova and I. G. Nasenkova. M .: Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies, 2015

Information