Third Republic Bombers

Only in November 1914, through 3 a month after the outbreak of hostilities on the Western Front of World War I, was the 1-I Bomber Air Force of France established, and then, in less than 6 months, four more others.

From May to September 1915, the raids of the 1, 2 and 3 bomber air groups equipped with Voisin planes raised unfounded optimistic hopes.

But due to the appearance of effective German fighters in 1915, the crisis day began to develop in the development of daytime bomber aviation.

Opposition to German fighter aircraft caused heavy losses to the French. Slow and slow, unable to fire back, Voisin was ill-equipped for defense against enemy fighters.

Already in July, the 1915 of the command of the 3 Bombing Air Force ordered that the bombing should be carried out only at sunrise or at nightfall. From October 1915, day bombers were carried out only under the cover of fighters and for a short distance - 20-40 km from the front line.

The day-to-day bombing crisis was so serious that by March 1916, the squadrons of the 1, 2, and 3 bomber air groups had already specialized almost exclusively in night bombing.

The only aircraft capable of performing daytime bombing operations were the twin-engine G-4 Codrons, which, in particular, were armed with the S-66 squadron that made a raid on Karlsruhe in June 1916.

The 4-I Bomber Air Force operating in Lorraine had planes like Maurice Farman, albeit more agile than the Voisins, but equally incapable of defense from the rear.

This air group carried out raids on Alsace and the Duchy of Baden (Friborg), but at the cost of heavy losses and with insignificant tactical results. These attacks were carried out by 4 - 5 aircraft, occasionally - a dozen cars.

As a result, the 1-I Bomber Air Company transferred 3 its squadrons to the Fighter Aviation (squadrons No. 102, 103, 112), the 2-I Bombing Air Group was disbanded, transferred three of the same structure, I’ve turned out to I’m, I’ve left I’m to I’m now I’ve been able to do this, I’ve turned on I’ve been in charge, I’ve turned on I’m using my own squadron, I’ve transferred my own squadron, I’ve transferred I, I’m now I am 104). The S-105 squadron was temporarily assigned to the 106 Army, and took part in the attack on the Somme as a reconnaissance unit.

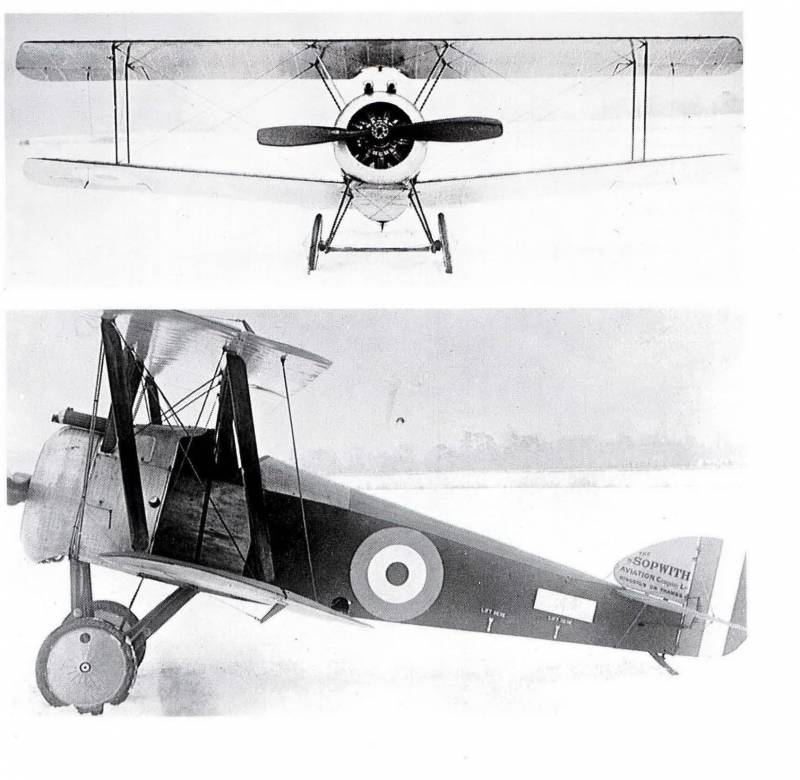

In 1917, the French day-to-day bomber squadrons were reequipped for single and double Sopvichi. This allowed them to resume their work, but rather timidly, and without leaving the near-bombing zones.

Although Sopvich had really good flight data, he appeared on the French front with a delay of a year, and the French version of the aircraft, made according to the English models, lagged behind the latter qualitatively.

Under such conditions, squadrons of the 1 and 3 of the daytime Bomber Air Group participated in the attack on the r. En (April - May); the squadron of the 1 th air group was on the offensive near Verdun (August and September), and no deep raid into the enemy’s defenses was carried out by the bombers.

In Lorraine, the 4-I Bomber Air Force, also re-armed with Sopwits, carried out several raids on Alsace and the Duchy of Baden, interacting with several English squadrons.

The losses, however, were heavy, and with the exception of a few group raids (Friborg, Oberndorf), the operations of the 4 Bombing Air Group were more and more reduced to night raids by individual aircraft or to raids on nearby enemy rear forces in Upper Alsace.

The number of daytime bombings of the French Air Force was as follows:

a) Targets distant from the front not further than 30 km: in 1915, 18; in 1916, 9; in 1917, the city (until August) - 2; from September 1917-th to 21-th of March 1918-th - 26; from March 21, 1918, to the Armistice, 6. Accordingly, all - 61 bombing.

b) Targets remote from the front not further than 60-km: in 1915-m - August of 1917-th. - 15; in September 1917 th - November 1918 th. - 11. Total - 26 raids.

c) For targets located at a distance greater than 100 km, there are only 6 raids belonging to the period before September 1917.

However, if during this period, daytime bombardment achieved inconsequential results, it played a more significant role on the battlefields of 1918.

Moreover, the Germans and daytime group bombing were very rare and were conducted at a small distance from the front line - for example, on the city of Nancy or Bar le Duc.

Paris, except for single bombs dropped on it in 1914, the year when fighter aircraft did not exist, was bombed from the air only at night - and then only in 1918. During this period, the capital was only 80 km from the front. No matter how tempting a similar target to an adversary was, he never ventured to attack her in the daytime. The enemy could achieve this goal at any time of the day - but after all, it was not only the squadrons located near Paris who were waiting for him. The Germans knew that on the way back they would face the barrage of front-line fighter groups of allies, who would arrange a battle for the returning bombers.

At the same time, the British Air Force squadrons from Lorraine from October 1917 to November 1918 made successful day raids on the centers of the Rhineland. Moreover, some of them were conducted at a great distance from the front, for example, in Mannheim (120 km), Koblenz (200 km), Cologne (250 km, bombarded by 18 in May 1918).

Given the weak defenses of the French Air Force's first day bombers, as early as the 1915 of the 2 Bomber Air Force, deployed in northern Lorraine, fighter squadrons were assigned - No. 65 (on Newpore) and No. 66 (on Codrons).

In the 1917 year, during the attacks on the river. En in Champagne and Verdun, the Sopvichi bombers operated under the direct protection of single-seat Recession fighters. Thus, in Alsace, the cover of the 4 Bombing Air Group was assigned to the 7 Army Fighter Squadrons located in the Belfort area. In addition, this air group had several single-seat fighter Newpore.

From September 1917 of the year to 21 of March of 1918, when the German fighter aircraft had the Pfalz, Albatross and Fokker planes, 180 HP Spadam, which could not fight at altitudes over 5 thousand meters (height, normal for daytime bombers) had to be tight.

But after the Breguet 1918B aircraft appeared on the front of 14 in February - March, the situation changed. But the Germans opposed them to the new machines - first of all, the Siemens-Schukkert single-seat fighter.

As a result, even under fighter cover, squadrons of French daytime bombers rarely covered the distance of 12-15 km from the front line, not even reaching the enemy’s operational reserves.

The idea of fighter cover for the French Air Force bombers was revived again in the spring of 1918, in the form of the so-called "combined raids" of fighter and bombing squadrons. A typical example of such operations are raids on the airfield in Kapni, carried out by the 12 (bomber) and 1 (fighter) squadrons.

Despite the powerful fighter cover (May 16 - 56 Spads and Breguet 23), they were not without losses. So, on May 17, 2 Breguet was shot down, and the third plane brought the killed observer pilot to the airfield.

The role of the direct cover of the bombers was assigned to the squadron of the triple Codrons, which form an integral part of the strike groups.

The effectiveness of covering the bombers is evidenced by the losses suffered by the Allied day bombers in the 1918 campaign of the year.

Thus, in the period of May 1 - June 14, 5 bomber air groups with a total of up to 150 aircraft took part in operations.

From 29 on May to 14 on June, i.e., for 15 days of combat activity, with 1350 on the aircraft sorties, losses were 25 aircraft and 72 pilot (50 missing people, 4 killed, 18 injured). The greatest losses were incurred in the battles of 31 on May (8 aircraft) and 1 on June (4 aircraft).

From 1 to 26 on May 650, the losses were 12 aircraft and 37 pilots (24 missing, 6 dead and 7 injured).

Significant losses were swept and later. For example, on September 12, the Germans shot down an 3 aircraft, including Major Roccara, the commander of the 4 Bombing Air Group.

On September 14, 8 aircraft were also shot down by the enemy. 33 pilots, observers and machine gunners were out of action from the 20's crews that took part in the raid. In this battle, the French units were attacked by approximately 20 th enemy fighters - a fierce struggle lasted 35 minutes. But in this battle 8 single German planes were shot down or shot down (but, considering that single planes, the Germans lost about half the people).

The fierce battles were fought and British pilots. So, on July 31 of 1918 of Mr. 9, the airplanes of the British long-range squadron in Lorraine flew out, intending to launch a bombing attack on the city of Mainz. Soon attacked by numerous enemy aircraft, they lost the 4 aircraft. Five others managed to drop bombs on Saarbrück, but a new skirmish on the way back resulted in the death of another 3 aircraft.

In July, only two British squadrons (No. 1918 and 55) lost in the air battles 99 downed and 15 damaged aircraft (two-seater Hylandsand) in July 28. The losses of enemy fighters in these battles were equal to 10-shot down and 6-damaged aircraft.

You can only bow to the daring of the crews of the allies, who neglected the attacks of enemy aircraft during the bomber raids.

The average numbers of Allied casualties were about twice as large as the corresponding losses suffered by German aircraft in the same battles.

Such losses were swept by the Allies, including because they had a very small number of easily replenished combat units, which could not be “renewed” all the time - in the presence of numerous air groups. In addition, the British, less depleted by the war than the French, were less prudent about the lives of their fighters (the same circumstance, and to an even greater degree, was noticed in relation to the American army, which had fought completely fresh and at the final stage of the First World War) .

If the Allies more actively practiced daytime bombing, even with a destructive cover, this would only lead to the unacceptable waste of material and human resources of their air force.

The struggle in the air was a mixed success.

The most effective day bomber aircraft was from May to October of the 1915 year and from September of the 1917 year to March of the 1918 year - and its success was primarily due to the short-term superiority of Allied fighter aircraft over enemy aircraft. Although such superiority was maintained for no longer than several months each time, it was the fighters that made it possible for the aircraft to achieve daytime bomber aviation with appropriate combat successes.

Day bombers of the French Air Force carried out their difficult mission, bringing the day of victory over Germany to the best of their ability.

Il 1. Sopwith F-1, 1916. Vruce JM Sopwith Camel. London 1991.

Fig. 2. Codron G 3. September 1917. Woolley Charles. First to the front. The aerial adventures of 1st Lt. Waldo Heinrichs and the 95th Aero Squadron 1917-1918. London, 1999.

Information