5 legendary swords of medieval Europe

Excalibur

According to legend, Excalibur is often confused with a sword in stone, which will be discussed below. Both of these swords belonged to King Arthur, who himself is a great mystery to historians. Despite popular opinion, most of the original sources speak of them as different blades.

Excalibur or Caliburn - another sword of King Arthur, the legendary leader of the Britons, who lived around the V-VI centuries. The epos about the king and his loyal subjects is very extensive and includes a complete list of heroic adventures: the salvation of beautiful ladies, the battle with the monstrous dragon, the search for the Holy Grail and just successful military campaigns. The sword is not just a weapon, but a status symbol of the owner. Of course, such an outstanding person as Arthur simply could not have an ordinary sword: in addition to excellent technical characteristics (which was indeed an outstanding achievement for the Dark Ages), the magic properties are also attributed to the sword.

Before romanization, the name of the sword most likely originated from the Welsh Caledfwlch: caled (“battle”) and bwlch (“destroy, tear”). According to legend, the king got the sword with the help of the wizard Merlin and the mysterious Virgin of the Lake, instead of lost in the battle with Sir Pelinor. The sheath of the sword was also magic - they accelerated the healing of the wounds of the owner. Before his death, Arthur insisted that the sword be again thrown into the lake and thus returned to his first mistress. The abundance of swords of the Dark Ages period, found by archeologists at the bottom of various reservoirs, allowed them to assume that in those times there was a custom of submerging weapons in water after the death of a warrior.

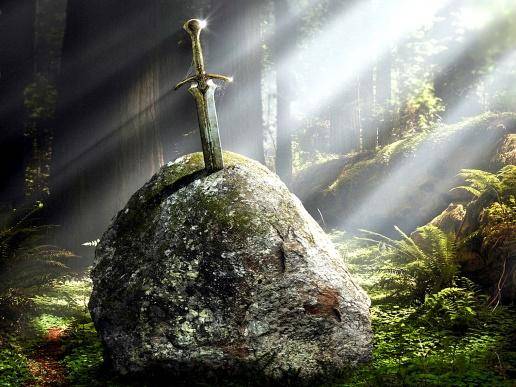

Sword in stone

The sword in stone, which according to legend, the king himself plunged into the rock, proving his right to the throne, has a curious relative who has come down to our days. It is about a boulder with a blade firmly entrenched in it, which is kept in the Italian chapel of Monte Ciepi. The master of the sword was, however, not the legendary king, but the Tuscan knight Galliano Gvidotti, who lived in the 12th century. There is a funny story connected with him: one day, to Gvidotti, who, like many knights of that time, led a dissolute life and was a cheeky snapper, the archangel Michael himself appeared and demanded that Galliano relinquish his knightly vow and become a monk. In response, the knight with a laugh said that it would be as easy for him to become a servant of the Lord, as well as to cut a stone. Rubbing the nearest boulder to prove his words, Guidotti was amazed: the blade easily entered him like a knife into butter. Of course, after this, Galliano immediately embarked on the righteous path and later even received canonization.

According to the results of radiocarbon analysis, the legend really does not lie: the age of the boulder and the sword stuck in it coincides with the approximate lifetime of a knight.

Durendal

Durendal is another sword in stone. It was owned by Roland, a real knight, who later became the hero of numerous sagas and ballads. According to the legend, during the defense of the Not-Dame chapel in the city of Rocamadour, he threw his blade off the wall and he remained hanging around it, sowing firmly in the stone. It is noteworthy that there really is a blade in the rock near the chapel: thanks to the skillful public relations of the monks who actively spread the legend of Durandal, the chapel quickly became the center of pilgrimage for parishioners from all over Europe.

Scientists, however, question this fact and believe that the chapel is not at all the legendary Roland's magic sword. First of all, the banal logic is lame: Durendal is a female name, and the hero, it seems, had a real passion for him. It is doubtful that he began to throw away such valuable and dear to the heart weapon. The chronology also fails: the loyal subject of Charlemagne himself died according to historical evidence on 15 in August 778 in the battle of the Ronneval Gorge, which is several hundred kilometers from Rocamadour. The first evidence of the sword appeared much later - in the middle of the XII century, at about the same time when the famous "Song of Roland" was written. The original owner of the blade in the chapel was never installed: in 2011, the blade was removed from stone and sent to the Paris Museum of the Middle Ages.

Sword of wallace

The huge broadsword, according to legend, belonged to Sir William Wallace, the leader of the Scottish Highlanders in the battle for independence from England. The famous knight lived in the period from 1270 to 1305 and, apparently, had remarkable strength. The length of the sword is 163 cm, which, with its weight in 2,7, makes it a weapon of great power, which requires the owner to use his skills and daily training. As you know, the Scots had a passion for two-handed swords - it is worth remembering the claymore, which in a certain historical period became a real symbol of the Scottish kingdom.

The sheath for such an impressive weapon is not easy to make, and the material was very unusual. After the battle at Stirling Bridge, where the sword and its master gained fame and honor, the blade acquired a scabbard and sword belt made from human skin. Its owner was the English treasurer, Hugh Cressingham, who "tore off three skins from the Scots and received a deserved reward." Scientists are still arguing about the authenticity of the ancient relics: due to the fact that King Jacob IV Shotlsky at one time presented the sword with a new handle and decoration to replace the worn old, it is very difficult to establish historical authenticity.

Ulfbert

“Ulfbert” is not one, but a whole family of Carolingian-type medieval swords dated between the 9th and 11th centuries. Unlike their legendary counterparts, magic properties are not attributed to them. Much more important is that for the early Middle Ages, these blades differed not only in mass, but also extremely high quality workmanship. Their hallmark was the + VLFBERHT + stamp at the base of the blade.

In those days, most European swords were made on the principle of "false Damascus": cast from low carbon steel with a high degree of slag impurities, these blades only visually resembled the famous Damascus steel. The Vikings, being sea merchants, appeared to buy crucible steel in Iran and Afghanistan, much more durable and reliable. For the Middle Ages, it was a real breakthrough in blacksmithing, and therefore such swords were valued very highly: weapons of comparable strength in Europe were mass produced only in the second half of the XVIII (!) Century.

Information