Fourth power on the battlefield

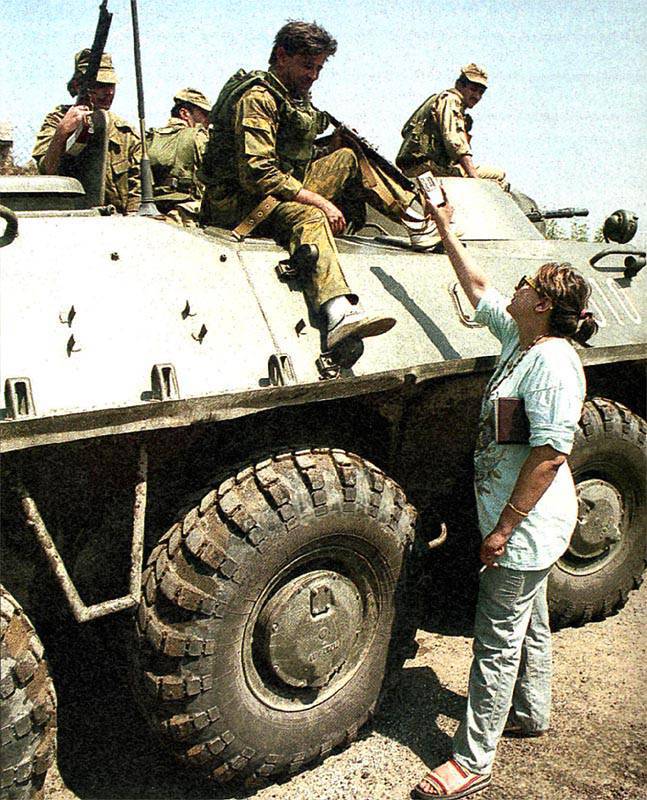

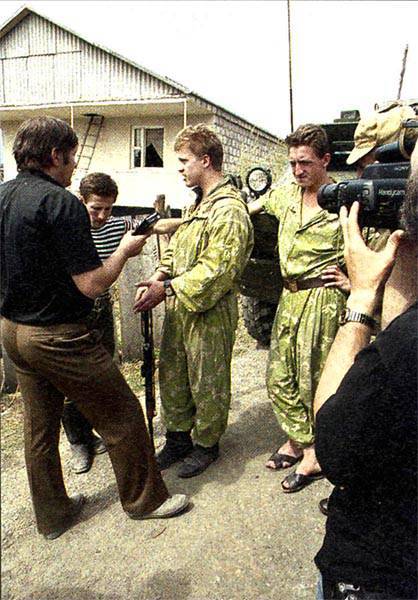

Relations between the media and the army in Russia have never been so bad until the Chechen war brought them into open hostility. Since then, the flow of recriminations and insults has not waned. The military said that the press and television were biased, incompetent, unpatriotic, and even corrupt. In response, they heard that the army is mired in corruption, is not capable and tries to hide the ugly truth from the people, blaming its sins on journalists. Neither the army, depriving themselves of the opportunity to influence public opinion, the media losing access to an important body of information, or, finally, the society financing the army and having the right to know what the hell is happening, are objectively interested in this conflict.

The acuteness of the relationship was partly due to the fact that the commanding staff of the Russian army grew up at a time when they only wrote about it well. Public criticism from the mouth of the civil "weaver" then became a novelty for them.

In countries with so-called democratic traditions and a press independent of the state, the tense relationship between the media and the military is a common thing, a routine. Even in the USA, where respect for freedom of speech is absorbed with mother’s milk, in a number of studies the military spoke extremely negatively about the press: “Journalists are egoists by definition ... They only think about how to become famous and how to promote the circulation of their publications” (Major Air Force Little) or “Press is driven by greed. The military is driven by selfless service to the country ”(Lieutenant Colonel George Rosenberger).

Objectively, the principles by which the army lives and by which the press lives are incompatible by a huge number of points. The army is impossible without secrets - the media stand on the desire to find them out and publish before competitors. The army is hierarchical and built on tough discipline - the press is anarchic, does not recognize authority and always doubts everything. And so on.

Tensions increase during periods when the army conducts military operations, and especially during periods of unsuccessful military operations. Unsurprisingly, 52 percent of the interviewed American generals who served in Vietnam, argued that American television during the war was chasing sensations, and not truth, and considered his activities "interfering with victory."

Of course, there is another point of view: “It was not the service of television news that harmed the army. She was harmed by the untenable policy of the leadership, who had no recipes for victory. Fixing such insolvency by means of the media is certainly among the highest interests of the nation ”(coast guard lieutenant Michael Nolan). The point is not which of these positions is correct. The fact is that the Pentagon considers discontent with the press and TV as an excuse not for a “divorce” with them, but for searching for new forms of cooperation. The military may not like what the journalists write and say about them. But they understand that if they want to hear something else, they have to go towards journalists, and not push them away.

War on two fronts

Vietnam War - the longest in the American stories, and the media attended to it from the very beginning. Since there was no press service in the US Army in Vietnam and there was no front line in the usual sense, journalists could, in principle, go anywhere. Formally, accreditation was required, but its procedure was simplified to the limit.

In the early years of the Vietnam War, the army enjoyed media support.

But with the expansion of hostilities and the involvement in them of all the new parts of the US Army, public opinion, which at first had a negative attitude towards criticism of the Pentagon, began to lean in another direction. This happened as trust in the Washington administration fell. Up to 1968, the president and military leaders told the Americans that victory was just around the corner. But the Vietnamese offensive on the holiday of Tet 1968 of the year hammered a wedge between the army and the media. Although militarily the offensive was a defeat, the Vietcong propaganda victory was indisputable. Its main purpose was not the Vietnamese, but the Americans. The Viet Cong showed them that the victorious press releases of Washington, in which the guerrilla forces were declared broken and destroyed, were lies. Especially forced journalists to whip up the assault on the American embassy in Saigon. The "crushed" Vietnamese showed the American people that they were able to find themselves at any point and do what they liked, and they showed it with the help of the American media.

Tet's offensive has become a watershed in the relationship between the army and journalists. President Richard Nixon later wrote in his memoirs: “More than before, television began to show human suffering and sacrifice. Whatever goals were set, the result was a complete demoralization of the public at home, calling into question the very ability of the nation to consolidate in the face of the need to wage war somewhere far from the borders of the country. ” A reviewer for Newsweek magazine Kenneth Crawford gave such grounds for writing that Vietnam was "the first war in American history, when the media were friendlier towards our enemies than allies."

The Vietnam War demonstrated for the first time, according to the commentator James Reston, that “in the age of mass communications under the lenses of cameras, a democratic country is no longer able to wage even a limited war despite the moods and desires of its citizens.” So mass media became a real military force. Naturally, awareness of this fact did not improve relations between the US Army and the press. The administration of President Lyndon Johnson, not being able to block anti-war information, launched a powerful propaganda campaign in support of the war in the face of the “second front”. This meant a whole series of press conferences, press releases and interviews distributed by the commanders in Saigon and Washington in order to convince the media of the clear progress in the hostilities. The then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara betrayed a mountain of numbers: the number of enemies killed, captured weapons, pacified villages and so on. But since the victory did not come all, the reputation of a number of professional military turned out to be stained. Hardest hit was the commander-in-chief of the American troops in Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, whom President Johnson particularly actively pushed for public promises.

Injured by the defeat of the United States in Vietnam, many officers began to look for explanations of what had happened. It was so natural to put some of the blame on television news every night, which regularly showed corpses, destruction, fires and other ordinary signs of war to the inhabitant. As a result, even a militarily successful operation in a short report looked more or less massacre, unwittingly raising the question of whether all this was worth the loss of human lives.

Westmoreland described it this way: “Television is doomed to create a distorted view of events. The report should be short and intense, as a result of which the war, which the Americans saw, looked extremely cruel, monstrous and unfair. ”

However, the press was something to argue. “American society was restored not against the war, but to casualties,” said military historian William Hammond. “The number of supporters of the war in polls fell by 15 percent whenever the number of victims changed by an order of magnitude.” Vietnam has for many long years undermined the confidence of the media and society in government information. Once making sure that Washington is lying, the press further met any statement from the federal government as yet another deception or half-truth. In the end, the journalists said, the government’s business is to convince the people that the war that it is starting and leading is right and necessary. And if officials fail to cope with this task, blame them, not us.

Fury without borders

In 1983, American troops landed in Grenada, a small island in the Atlantic. Operation Rage was led by senior officers in Vietnam commanding platoons. They brought to Grenada their memories of the media, and therefore in this operation the American armed forces of the media were simply ignored. Formally, “putting the press behind the brackets” was explained by considerations of security, secrecy and transport restrictions. Later, however, Defense Minister Casper Weinberger disowned this decision and pointed to the commander of the operation, Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf. Metcalfe, in turn, denied that the isolation of the press was a planned act, and was justified by the fact that 39 hours were assigned to the development of the whole Operation Rage. But no one doubted that the main reason for which he left journalists “overboard” was the fear and unwillingness of the reports in “Vietnamese style”.

The press, of course, was furious. Not only did nobody help them get to Grenada, but the military also found a reporter who accidentally appeared on the island at the time the operation began, and took him to the flagship. And the sea aviation attacked the boat with reporters trying to get to Grenada on their own, almost sunk it and forced it to turn back.

369 American and foreign journalists waited two days in Barbados until they were allowed to go to Grenada. Finally, on the third day, the military started up, but not all, but by forming a so-called pool: a group of representatives from various newspapers, news agencies and TV companies. A feature of the pooled pool system that was first applied was that the journalists were supposed to keep the group, they were shown only what the accompanying soldiers considered necessary, and they had to provide information not only for their publications, but also for other interested media.

Press protests were so strong that the Pentagon created a special commission. In 1984, she issued a list of recommendations on how the army works with the media. The main advice was that planning for work with the media was part of the overall plan of the military operation. It was also supposed to assist journalists in matters of communication and movement. It was recommended to continue the formation of journalistic pools in cases where the free access of the entire press to the combat zone is impossible. Casper Weinberger accepted the advice for execution. And soon the army turned up a reason to test them in practice.

Our cause is right

In December 1989, the United States decided to eliminate Panama's dictator Manuel Noriega. Operation Just Cause was unique in its own way (see details about this operation >>>). In one night, a large number of special forces groups were to simultaneously attack multiple targets in Panama. This made it possible to gain additional superiority in battle and avoid unnecessary casualties among the civilian population. In addition, by the time the journalists managed to at least hint at the possibility of failure, everything would have been over.

President George W. Bush demanded that the press’s reaction options be calculated before and during Operation Just Cause. In a special report, presidential spokesman Marlin Fitzwater convinced Bush that a generally positive reaction was expected, but separate criticism was not excluded. The operation at night, however, promised that by morning, by the first television news, the army would at least succeed in some areas, to which it would be possible to attract media attention.

Although militarily the operation went well, in terms of working with journalists, it turned out to be a complete disaster. The plane with the pool was late for Panama by five hours. Then the arrivals were kept all the time away from the combat zone. As for the rest of the press, for some reason the Southern Tactical Command was expected by a 25 – 30 man, and not by a factor of ten more. As a result, all those who arrived were gathered at Howard Air Base, where State Department representatives “fed” them with filtered information, which became obsolete faster than it was reported, and CNN television reports.

As after Grenada, the Pentagon had to form a commission, One of its recommendations was to reduce the level of guardianship of journalists and the secrecy of what was happening. The press has also drawn its conclusions: its equipment should be lighter and more autonomous, and one should rely only on oneself in terms of movement.

Nine months later, in August 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait ...

From “Shield” to “Bure”

Saudi Arabia has agreed to take a pool of American journalists, provided that they will be accompanied by the US military. Quickly formed a group of 17 people representing radio, TV and newspapers located in Washington. With the exception of the first two weeks of work, they were able to move freely, look for sources of information, and observe in detail the development of Operation Shield in the Desert into Operation Storm in the Desert.

At first, the largest national media were quite critical. They wrote about the confusion, about the unpreparedness of troops and their equipment for operations in the desert, the low morale of the soldiers. However, later, journalists from small local newspapers and television stations began to arrive in Saudi Arabia in increasing numbers to talk about military units and even individual countryman soldiers. By December, the number of media representatives in Riyadh had grown to 800. They brought the army closer to the average American, made it clearer and more humane. A campaign “Support our troops” has been launched in the province. National media found that negative "is not for sale." Patriotism has become fashionable again. Opinion polls demonstrated, as once, absolute support for government foreign policy. And the tone of the major media reports began to change.

The Ministry of Defense has stopped worrying about negative publications. Pentagon press secretary Pete Williams, formulating his service’s approach to reporting from Kuwait, compared it with the rules established by General Eisenhower before the Allied invasion of France in 1944 or MacArthur during the Korean War: “Write whatever you like, if it isn’t threat of war plans and the lives of soldiers. " Mandatory for the press rules prohibited the “description of details of future operations, disclosure of data on weapons and equipment of individual parts, the status of certain positions, if the latter can be used by the enemy to the detriment of the US Army.”

During the fighting, journalists were obliged to follow certain rules established by the command. The most important of them is that not members of the pool were allowed into the forward units, and all movements here were carried out only accompanied by a public relations officer. All civilians who found themselves in the location of the forward units without special permission were immediately expelled.

American censorship

Finally, the military installed a system for previewing texts prior to their publication. The press reacted extremely negatively to this innovation, from which a mile off smelled of anti-constitutional censorship. The military did not think so: they said that they could not prohibit printing any material, but they wanted to be able, firstly, to control what kind of information becomes publicly available, secondly, to appeal to the common sense and patriotism of editors, if cases of breaking the rules. After the Gulf War, it was estimated that the military took advantage of this only in five cases of the 1351 possible. Radio and television coverage was not monitored at all.

There were other problems. So, reports from advanced parts were transported by motor transport to the central information bureau of coalition forces, and from there they were sent to publications — which, by the standards of American newspapers, is unacceptably slow. The army set the example of the marines, which provided journalists with computers with modems and fax machines. A lot of complaints have been reported about the unpreparedness of public relations officers who escorted the press.

While the army as a whole was pleased with the result, the reaction of the media was quite harsh. “From beginning to end, the pool was the last place to get some sensible information,” wrote Newsweek observer Jonathan Olter. And although according to 59 polls, the percentages of Americans after the Gulf War began to think about mass media better than before, many expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that the press and TV allowed themselves to be fed information from the army, instead of extracting it themselves.

During the war, the military was convinced that daily press conferences and press briefings were the only possible way for them to convey their views to the public. In addition, it ensured that the media did not receive redundant information on intelligence, tactics and movement of units. However, at first they trusted the press conference to middle-level officers who were not too self-confident, nervous in front of lenses and microphones and timid to answer the most innocent questions. From their speeches, it was not the image of the army that the military dreamed about. This practice was quickly abandoned, instructing press conferences in Riyadh to Brigadier General of the Marine Corps Richard Neil, in Washington - to Lieutenant General Thomas Kelly.

The power of the fourth power

The Desert Storm demonstrated the tremendous power of the fourth power in the context of modern communications and a democratic society. When a CNN reporter, Peter Arnett, who worked in the bombed Baghdad, showed the whole world (including Russia) the results of the air attack on the Al-Firdos 13 command bunker February 1991 of the year, it affected the planning of further bomb strikes on Iraq. The spectacle of children's and women's corpses turned out to be so terrible that the thousands of words that the Pentagon spent on explaining the cunning of the Iraqis who had built a bomb shelter over a secret object did little to change. Having felt the threat, the US government was forced to change the strike plan in such a way that no such object in Baghdad was attacked any more during the entire war.

The flight of Iraqis from Kuwait has created a giant traffic jam on the highway to Basra. American pilots bombed the Iraqi Republican Guard convoy here, and this section was called the "highway of death." Under this name, it appeared in television reports after, following the liberation of Kuwait, reporters were taken to this part of the territory. Viewers all over the world saw a four-lane highway full of burned and turned over remains of thousands of cars, trucks, armored personnel carriers. This could not be anything other than a meat grinder, built from the air by American pilots. The report caused a shock not only in the United States, but also in the allied countries, which resulted in rather nervous requests through diplomatic channels from England and France.

And although Norman Schwarzkopf knew well, as other officers knew, that at the time of the bombing of the Iraqi military convoy, these thousands of vehicles, mostly stolen or requisitioned in Kuwait, were thrown into traffic jam long ago, terrible destruction scenes strongly shaken public confidence in the need achieve all stated strategic goals.

At the end of the fighting, the military again sat down at the negotiating table with the press. The next agreement included eight points. The most important was the condition that open and independent coverage of military operations is an immutable rule. Pools can be used in the initial stages of a conflict, but they must be dissolved no later than 36 hours from the moment of organization. The army should provide journalists with mobility and means of transport, provide means of communication, but not limit the use of their own means of communication. For its part, the press pledged to abide by clear and precise rules of security and regime established by the army in the combat zone, and to send only experienced, trained journalists to the conflict zone.

Two lessons on one topic

When US Marine Corps landed at night in Mogadishu (Somalia) in December of 1992, an unpleasant surprise awaited her. American marines lit dozens of camera lights, leading live coverage of such an exciting event. The positions were unmasked, the ultra-sensitive night-vision equipment refused to work, and the marines themselves felt like targets at a shooting range for Somali snipers. The military were beside themselves. However, the events in Mogadishu had a special background.

Initially, the Pentagon welcomed the appearance of reporters at the landing point, because I wanted to emphasize the role of the army in the whole operation. Later, however, strategists in Washington realized what was happening and instructed the media not to approach the coast. Unfortunately, this warning was late, and many news agencies did not know about it. The command could no longer keep the date and place of landing a secret if reporters arrived in Somalia in advance and prepared to meet the marines.

That which had begun so badly could not have ended safely. All US publications bypassed photos of Somalis, dragging down the street by the feet of a dead American soldier. The victim was a member of a group of rangers sent to arrest General Aidid. The rising storm of public indignation proved stronger than any argument for the US presence in Somalia. Voters demanded the Congress to immediately withdraw American troops from this country. 31 March 1994, the last American soldier left Somalia.

Unlike the Somali epic, the participation of the press in disembarking on Haiti (Operation Restore Democracy) was well thought out and successfully implemented. On the eve of the landing, on Saturday 17 of September 1994 of the year, in secret, the military convened a journalistic pool, and he was in a state of full readiness in case of serious hostilities. Clifford Bernat, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, met with media representatives to discuss how to cover the operation. Negotiations were held on seven positions, which in the past had problems, in particular the ill-fated lights of television. In four positions, including the use of lighting, the media accepted the conditions of the military. By three, agreement could not be reached. The military could not convince the media to observe a time moratorium on the information on the initial location of the units, not to leave the hotels and the embassy until the streets were deemed safe, and not to climb to the rooftops. Journalists said that their security is a personal matter to which the army has nothing to do.

Not one, but several pools were formed at once to follow the parts of the invasion. They even took into account the fact that a certain number of journalists are already on the island. Reporters got the full right to use their own communication devices, although the army communications centers were at their disposal. On the whole, both sides were satisfied: the press - with the fact that it was able to fully and quickly cover the events in Haiti, the military - with the fact that their actions were correctly and objectively presented to the American public.

The temptation of hedgehogs

Of course, the number of supporters of “tightening the screws” modeled on “Desert Storms” and Grenada in the army is still very large. The temptation to take the media in the muddy gloves is strong because it is easier than to seek a common language and forms of coexistence with them. However, there are several reasons why such a policy would harm the army itself.

One is associated with scientific and technological progress and the rapidly improving equipping of the media. Satellite phones, which the Russian military in Chechnya gazed with envy at, will become more and more widespread, guaranteeing the owners unprecedented independence and speed of communication with the editors. The next step will inevitably be a direct satellite broadcast from a video camera to the head office. This is the first time the world has been shown to CNN. As the cost of broadcasting equipment falls, it will be available not only for such giants. Coupled with the proliferation of miniature digital video cameras, this can drastically turn the idea of reporting from the front line.

The Internet allows you to transmit reports from the scene of an event, not even to a specific point, but directly to the world wide web, where they immediately become available to any user in any country. To this can be added a large number of photographic and video materials posted on the Internet by the users themselves without the participation of the media.

But even if we defend ourselves in the only possible way in this case - to limit the physical access of journalists to the zones of interest to them - then the largest informational conglomerates will use their last weapon: satellites combined with a worldwide network. Commercial space photo and video filming today is a reality, and as the resolution of optics grows, a space television report on military operations, even in a tightly closed area for a ground-based press, will be an increasingly simple matter. As futurologists Alvin and Heidi Toffler write in the book “War and Anti-War”, “private reconnaissance satellites will make it absolutely impossible for the warring parties to evade the all-seeing eye of the media and avoid immediately broadcasting to the whole world their any movements - tactics and strategies.

Finally, computer technologies make it possible for the media to model and launch any situations and scenes that never took place, but indistinguishable from real ones, or that took place in reality, but knowingly without witnesses, for example, episodes of atrocities of one of the armies or secret separate negotiations. Increasing the speed of transmission or broadcasting of materials will increase the risk of inaccuracies, and modeling reality for the needs of this media will remove this problem, although it will create a million others.

Nature does not tolerate emptiness

The second reason for which the army, including the Russian, will be forced to communicate with the media, is that the information side will immediately fill the information vacuum. No normal army will allow the reporter to cover the conflict on both sides, crossing the front line back and forth several times, as we saw in Chechnya. Not even because he may be a conscious traitor, but because of the possibility of accidentally disclosing undesirable information in the conversation. But no one will forbid a newspaper or a television station to have two representatives on both sides of the barricade - and if one is forced to remain silent, the other will dissuade both for himself and “for that guy.”

Predicting this development, the Americans are taking certain steps. Commanders of units and formations are instructed to spend more time with media representatives. They are assigned the task correctly, but energetically and in every case to instill in public the point of view of the army. They are taught to take the initiative and organize briefings and press conferences, including live, to act proactively and to offer their own vision of the issue before journalists do it for them. It is important to be sure that the desired image of the operation is not distorted by the media as a result of the negligence or mistakes of journalists. We need to think about the security of the army units, but at the same time it is impossible to lie to the press simply because it is more convenient.

One of the masters of this genre was considered Norman Schwarzkopf. He established four rules for communicating with journalists, who are not a sin to use by Russian generals: “First, do not let the press intimidate you. Secondly, you are not required to answer all questions. Third, do not answer the question if your answer will help the enemy. Fourth, do not lie to your people. ” Thanks to these rules, every performance of Schwarzkopf had a beneficial effect on the public and he always enjoyed the confidence of the media.

Colonel Warden, head of the college training the commanders and officers of the US Air Force headquarters, and the main planner of the US aviation action plan at the initial stage of Operation Desert Storm believes that the military has no choice but to come to terms with the existence of the media as part of a future battlefield . He writes that newspapers and TV should be treated "as a given, as if it were weather or terrain relief." As in the preparation of the operation, weather reports are analyzed, it is also necessary to take into account and predict the influence of the media on the performance of the combat mission - with a full understanding and acceptance of the fact that, as in the case with the weather, to change something not in our power. Soon the question in the headquarters: "What is our forecast for the press today?" - will become as natural as the question about the predictions of meteorologists.

Information