Cold South Ossetian summer of 1920

Truly Scorched Earth

On the very first day of the attack of Georgian troops on June 12, the village of Pris was burned. On June 12-13, the Ossetian settlement, a region of Tskhinvali, in which mainly Ossetians lived, was almost completely destroyed. On 14 of June the villages of Kohat, Sabolok, Klars and others were betrayed. On June 20, the aphid village burned, in which representatives of as many as four clans had once lived. Most of the villages from Tskhinval to the village of Verkhny Ruk Georgian troops burned.

Special “successes” in this fiery bacchanalia were achieved by Valiko Dzhugeli, one of the commanders of punitive Georgian detachments. This “people's guardsman” and “general” carefully recorded their actions in a kind of diaries, which were later published abroad under the title “Heavy Cross”. When the author read this artifact of Menshevik Georgia, he did not leave the feeling of psychological instability of Jugheli. His painful craving for fire was too obvious from the text:

Dzhugeli absolutely unashamedly describes the artillery shelling of mountain villages. He did not shy even when describing the ruin of Dzau (referring to him as Java in the Georgian manner), indicating that this was “the heart of South Ossetia” and “must be pulled out”. At the same time, Valiko justifies this by the struggle for "democracy." This song seems to be as old as the world.

Where Ossetian houses were not burned, they were mercilessly robbed, or even completely requisitioned. The story of Martha Matveevna Dzhigkaeva 1913 born in the village of Jer, recorded after known events by her relatives, is indicative:

Terrible outcome

Escape from their native places, when the native shelter erected in the harsh conditions of the mountains and, perhaps, standing in its place for decades, or even centuries, is enveloped in fire, a tragedy in itself. But the suddenness of the attack, the small number of fighters able to defend themselves, the persecution by the “people's guard”, the lack of supplies and snow-covered mountains turned the tragic outcome into what would now be called a humanitarian catastrophe, which goes hand in hand with genocide.

A fighter of one of the Ossetian detachments Viktor Gassiev recalled how sometimes they had to watch the death of compatriots in powerless anger. So, on 13 of June, during the evacuation of one of the villages, two women, a mother and daughter of 18 years old, lagged behind a group of refugees. The group discovered the disappearance of the villagers already on the mountain pass. Soon, in the valley by the stormy river, two figures of unhappy women were seen, followed by the Georgian "people's guard" on their heels. The intentions of the "guards" were not a secret. Therefore, in order to save the honor, the mother and daughter rushed from the steep bank in an instant swallowing their mountain stream.

The situation was not even better in the numerous wagons themselves. Cold, hunger and unbearably difficult road forced people to do unthinkable things. Here is how those days were remembered by the commander of one of the detachments, Mate Sanakoev (participant in the First World War, knight of the George Cross, knight of the orders of St. Anna of the 2 and 3 degrees, St. Stanislav of the 2 and 3 degrees, St. Vladimir of the 4 degree):

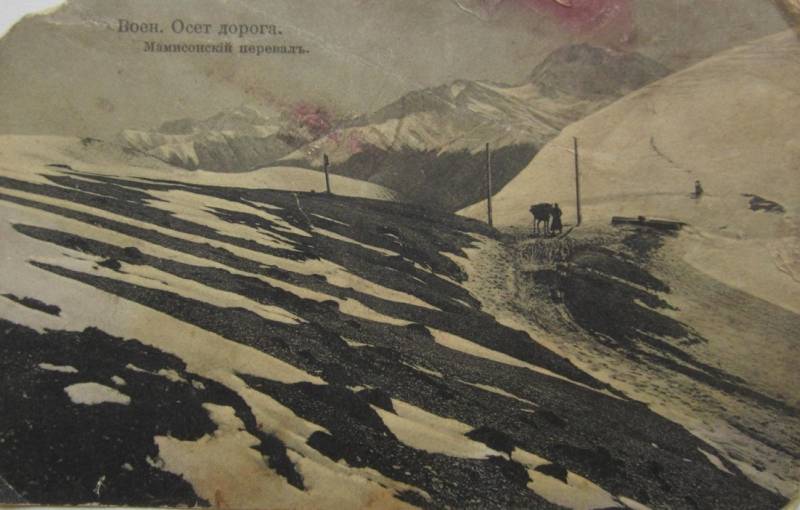

On the approach to the Main Caucasian Range, people were almost completely exhausted, and in front was the snowy Mamison Pass, rising 2911 meters above sea level. It is difficult to breathe in such places, but people walked with the children, hungry and frozen. Someone was simply blown away by an icy wind, someone in a starving dizziness fell into the crevices himself, and someone simply did not have enough strength. The exact number of refugees forever remaining in the icy highlands is unknown, maybe hundreds, maybe thousands.

Those who were lucky to force the pass and go to the villages of North Ossetia, faced with new difficulties. All of Russia was in a fever of revolutionary winds, and in the Caucasus, wherever you were at that time, party conflicts were aggravated by ethnic conflicts so characteristic of the region. Thus, the local authorities were completely unprepared to accept such a number of refugees: there was no food, no medicines, no decent housing, and people exhausted by the transition could only rely on the hardest work, literally for food. As a result, the refugees were scattered in several villages.

From the report of Markarov, a member of the commission to investigate the situation of refugees in South Ossetia in the Ossetian regional executive committee of the city of Vladikavkaz from 24 on August 1920:

From a telegram from the Congress of Soviets of the Vladikavkaz District to the Vladikavkaz Regional Committee, the Regional Committee, and the Refugee Arrangement Committee of June 24 on the 1920 of the year:

The death of those who did not escape

As indicated above, the vast majority of the population of South Ossetia fled from their native land to the north. But in the republic there were still those who either simply could not take off or hoped for poverty and remoteness of their own village. Moreover, partisans and underground workers remained in South Ossetia and even in its capital. Soon they were to split into living witnesses and dead victims.

After the capture of Tskhinval, the Georgian Menshevik authorities decided to "put things in order." Soon, 13 ethnic Ossetians were captured or arrested, among whom was an 16-year-old teenager. All of them were declared rebels and bandits and put in the basement. On 20 of June at three in the morning they were taken out into the street and taken to the outskirts of the city. There, in the presence of a doctor, Vaclav Hersh and a Georgian priest Alexei Kvanchakhadze, they tried to force them to dig a grave. 13 Ossetians resolutely refused, despite the beating. After that, Kvanchakhadze invited them to repent of the crimes, but was sent to the same address as the executioners. Finally, almost in the morning the Georgians started executing. After the first salvo, Ossetians finished off with single shots.

When, after the liberation of South Ossetia, an inquiry was carried out in this case of execution without trial, many interrogated persons supplemented the picture with new details. So, a participant in the execution of Gogia Kasradze during one of the drunks boasted that he personally shot nine Communards and kissed the barrel of his gun. Other witnesses showed that the priest Kvanchakhadze who participated in the executions, the one who asked to repent, often fell into euphoria and shouted: “Beat the Communists and Ossetians.”

Philip Ieseevich Makharadze, chairman of the Georgian Revolutionary Committee in the 1921 year, recalled the events as follows:

“The brutal People’s Guards, according to the directives of the government, N. Zhordania and N. Ramishvili did such horrors as very little is known to history ... The Georgian Mensheviks set themselves the goal of the complete destruction of South Ossetia and this goal was almost reached. It was impossible to go beyond this. Ossetia was destroyed and razed to the ground. "

The rampant violence stopped in the year 1921. In February 21, the Bolshevik troops attacked the Menshevik formations directly on the territory of Georgia. By the end of the month Tiflis was taken, and on 5 of March Tskhinval was liberated from the Mensheviks mainly by forces of Ossetian detachments formed in North Ossetia. Shortly after the victory of the Soviet regime in Georgia, a special commission was organized to investigate the consequences of hostilities in South Ossetia.

According to the commission, in the 1920 year in South Ossetia, the "people's guard" killed and died during the retreat and in the mountains of 5 thousand 279 people. 1 thousand 588 thousand residential and 2 thousand 639 farm buildings were burned. Almost the entire crop of 1920 of the year was destroyed, which for the agricultural region is akin to a death sentence. 32 thousand 460 cattle and 78 thousand 485 cattle died, i.e. virtually all livestock in the republic. However, these figures raise questions about the degree of reliability. Firstly, the commission for the most part consisted of ethnic Georgians. Secondly, it was problematic to count the victims who died on the mountain passes and in the gorges due to technical and weather conditions. Thirdly, it is not known whether the dead refugees in North Ossetia, who are known to have suffered from numerous diseases and were in extremely difficult conditions, were counted. All this has yet to be answered.

Information