Knights of Outremer

Worldly comfort.

I was glad to every temptation

I fell into sin.

The world attracts me with a smile.

He is so good!

Prickles I lost count.

Everything in the world is a lie.

Save me lord

So that I can overcome the world.

My path is to the Holy Land.

With Your cross I accept you.

Hartmann von Aue. Translation by V. Mikushevich

For the nearly ninety years that elapsed between the founding of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the defeat of the Christian army in Hattin in July 1187, the Outremer army was the only force that helped the Europeans to stay in Palestine. However, their composition was somewhat different than in the traditional feudal troops of the time. First of all, they included "armed pilgrims", for example, militant monks (ie, Knights Templar and Hospitallers). The most unusual, however, was that they were completely unknown in the West types of soldiers: sergeants and turkopuly. The system was also unusual: “backbang ban”, which was not used in Europe at that time! Let us get acquainted with the troops of Europeans in Palestine in more detail.

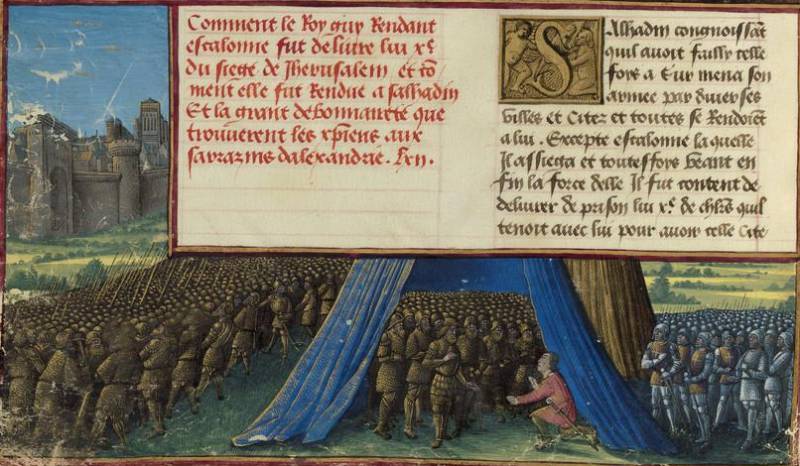

Council of Barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Sebastian Mamerot and George Castellian "History Outremer, written in 1474-1475's. (Bourges, France). National Library, Paris.

Barons and Knights

As in the West, the backbone of the army of Jerusalem consisted of knights who lived and armed themselves at the expense of income from the estates granted to them. It could be both secular lords (barons) and church (bishops and independent abbots). The latter exhibited about 100 knights each, and, judging by the records of John D'Ibelin, the bishop of Nazareth had to expose six knights, Lydda 10 knights, respectively.

It is important to remember that the term “knight” does not refer to one person, but describes a combat unit consisting of a knight on a warhorse plus one or several squires, as well as his riding horse (half-horse) and several pack horses. The knights were supposed to have armor and weapon. Squires - to have it all when possible.

The barons were supported by younger brothers and their adult sons, as well as "household knights", that is, people without land holdings who served the baron in exchange for annual wages (as a rule, these were payments in kind: table, services and apartment, as well as horse and weapon). John D'Ibelin assumes that the number of such knights took place in proportion from 1: 2 to 3: 2, which gives us a reason to at least double the list of knights of the Jerusalem kingdom going on the battlefield. But again this makes it difficult to count them. Someone they were, someone was not at all!

Surprisingly, the economic relations that they all entered into at the same time were often quite different from European ones. For example, Baron Ramle was obliged to set up four knights in exchange for the right to lease pastures to Bedouins. Often they were income from customs duties, tariffs and other royal sources of income. In the thriving coastal cities of the Outremer, there were many such "Lennists" who were liable to the King.

Part of the knights were recruited from the younger sons and brothers of the barons or to the army from among the landless armed pilgrims who want to stay in the Holy Land. At the same time, they took the lenten oath to the king and became his knights, and he fed them, armed and clothed them. In the West, this was just the beginning.

Armed pilgrims

The Holy Land, in contrast to the West, benefited from the fact that at any moment, but more often from April to October, attracted tens of thousands of pilgrims, both men and women, who brought great income to the kingdom, some of which went to “purchase” knights and other mercenaries, capable in the event of an emergency, get up and fight. Sometimes the barons brought with them small private armies of servants and volunteers who joined them, and these forces could also be used to protect the Holy Land. A good example is Count Philip of Flanders, who arrived in Akku in 1177 the year at the head of the “tangible army”. His army even included the English Counts of Essex and Meath. But more often, some knights were just pilgrims and went to fight only when necessary. One such example is Hugh VIII de Lusignan, Comte de la Marsh, who ended up in Palestine in 1165, but eventually died in the Saracen prison. Another example is William Marshall, who arrived in the Holy Land in 1184 year to fulfill the vow of the crusader given by his young king. That's how it happened! Therefore, it is impossible to know exactly how many “armed pilgrims” - and not only knights - took part in battles between the military forces of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and its opponents Muslims.

Knight monks

Another “anomaly” of the Outremer’s armies was, of course, large detachments of fighting monks — among which the Knights Templar and Hospitaller, the Knights of St. Lazarus, and a little later the Teutonic were the most famous. David Nicole in his book about the Battle of Hattin suggests that by the 1180, the Templars had about 300 people (only knights!), And 500 knights' hospitalists, but many of them were scattered around their castles and could not get together with a single force. It is indisputable that the 230 Templars and the Hospitallers survived the Battle of Hattin on July 6 1187. Considering that the battle lasted two days, it seems reasonable to assume that both orders suffered serious losses before the battle ended. It is likely, therefore, that there could be about 400 people, both hospitallers and Templars, and there were also knights of St. Lazarus, armed pilgrims from Europe and the knights of the King of Jerusalem, that is, an army of impressive forces.

Knights Outremer XIII century. The story of Outremer Guillome de Tire. White Thompson collection. British Library.

Infantry

In modern images of the medieval war, it is often overlooked that knights in medieval armies were the smallest contingent. The infantry was the main part of any feudal army and was far from being its excess component, although it was fighting in a different way than many people now imagine. Moreover, if in the West infantry in the XII - XIII centuries. consisted mainly of peasants (plus mercenaries), in the states of the Crusaders the infantry was recruited from free “burghers” who received land during the crusades, and of course mercenaries.

Saladin meets with Balyan II d'Ibelin. Sebastian Mamerot and George Castellian The Outremer Story, written in 1474-1475. (Bourges, France). National Library, Paris.

Mercenaries

If prostitution is the oldest profession on earth, then mercenaries should belong to the second oldest profession. Mercenaries were known in ancient Greece and ancient Egypt. In feudal time, the Lennians were obliged to serve their overlord for 40 days in a row, and someone had to serve in their place, when their turn ended ?! In addition, some military skills, such as archery and siege machine maintenance, required a great deal of experience and practice, which neither the knightly servants nor the peasants had. Mercenaries on medieval battlefields were everywhere. They were also in the Outremer, and probably were more common there than in the West. But without numbers in the hands of this you can not prove.

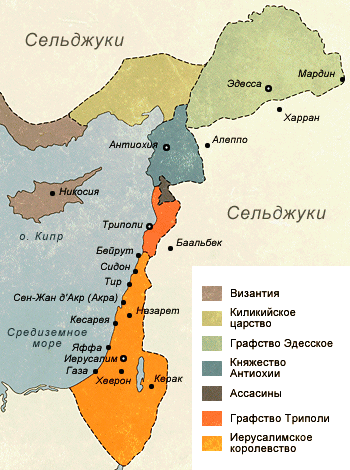

Crusader states in Outremer.

Sergeants

A much more interesting and unusual feature of the armies of the crusaders of the states were "sergeants". Because the “peasants” in the Outremer mainly consisted of Arabic-speaking Muslims, and the kings of Jerusalem were not inclined to rely on these people to force them to fight against their fellow believers. On the other hand, only one fifth of the population (ca. 140000 inhabitants) were Christians. All the settlers were communists and whether they settled in cities, like merchants and traders, or in agricultural areas on the royal and church lands, they were all classified as “burghers” - that is, not serfs. These members of the commune, who voluntarily arrived in the state of the Crusaders, automatically became free and had to go to military service if necessary, and it was then that they were classified as "sergeants."

The term “sergeant” in the context of the Outremer’s military practice is similar to the term “man with arms” of the era of the Hundred Years War. This means that he received money from representatives of the royal power to buy armor: quilted gambesons and stitched aketons or in rare cases of leather or chain armor, as well as a helmet and some kind of infantry weapon, spear, short sword, ax or morgenshtern. .

Battle of Al-Bugaya (1163). Sebastian Mamerot and George Castellian The Outremer Story, written in 1474-1475. (Bourges, France). National Library, Paris.

Not surprisingly, the sergeants were a burden for the cities, but the Templars and the Hospitallers contained significant powers of the "sergeants." And although they were not as well armed as knights, they were entitled to two horses and one squire! It is not clear, however, whether such installations were extended to sergeants of the king and church masters.

The Battle of 1187 Tire Sebastian Mamerot and George Castellian The Outremer Story, written in 1474-1475. (Bourges, France). National Library, Paris.

Turkopoules

Perhaps the most exotic component of the Outremer armies is the so-called Turkopules. There are many references to these troops in the records of the time, and they clearly played a significant role in the armed forces of the Crusaders, although there is no unequivocal definition of who and what they were. These were clearly “native” troops for those places, and it can be assumed that they were mercenaries from Muslims. Approximately half of the population in the Crusader states were, by the way, non-Latin Christians, and no doubt that from this segment of society it was also possible to recruit troops that hated Muslims. Armenians, for example, made up a significant part of the population in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, had their own neighborhoods and their own cathedrals there. Syrian Christians spoke Arabic and looked like "Arabs" and "Turks", but as Christians they were reliable troops. There were also Greek, Coptic, Ethiopian, and Maronite Christians, and all were theoretically subject to military service, and as Christians living in this region, probably gave the Latins ready warriors. They well remembered the insults and oppression of the Muslims, and here they were given the opportunity to get even with them.

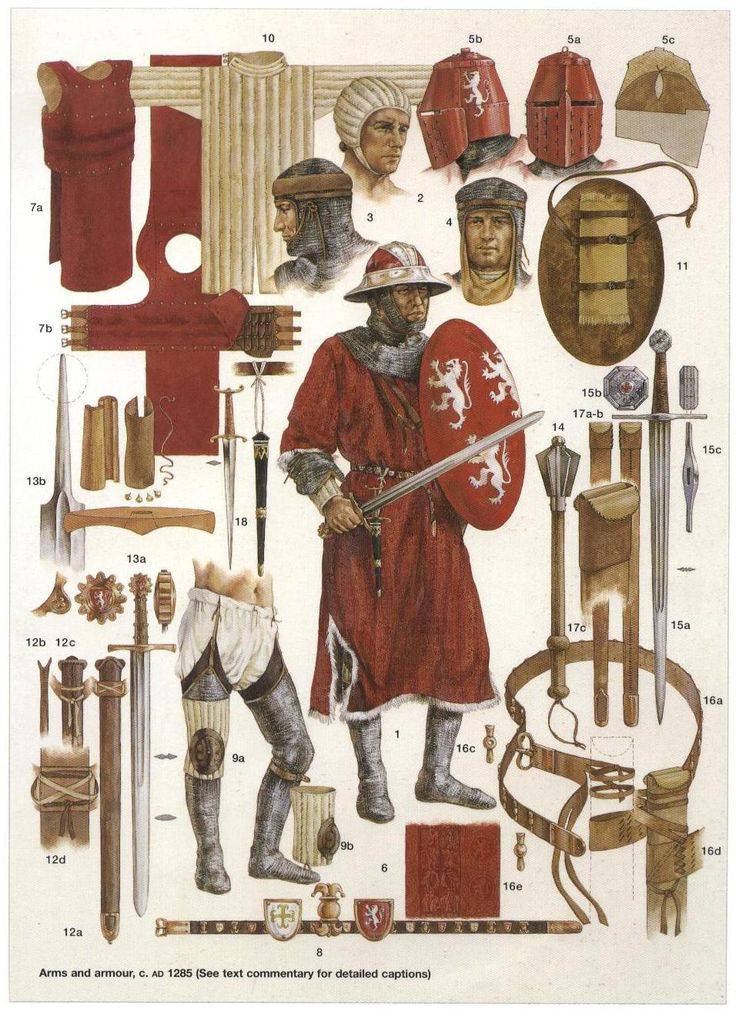

Knight Outremera. Figure A. McBride. Pay attention to how detailed every detail is worked out. Moreover, the swords are drawn according to the real samples described by E. Oakshot.

Areier ban

The kings of Jerusalem also had the right to declare a “rear ban”, according to which the free man was to stand up for the kingdom. In modern terms, this meant total mobilization. It is noteworthy that the king of Jerusalem could keep his vassals in the service for a year, not only 40 days, as in the West, but this was connected with the threat to the very existence of Christians in a particular area of the kingdom, or even the threat to the whole kingdom, the threat did not disappear, the troops did not disband! But if the king sent an army out of the kingdom for an offensive expedition, he had to pay his services to his subjects!

Information