Guria Republic How the Georgian county broke away from the Russian Empire

In Georgia, the autonomist and separatist sentiments were quite strong, some of whose supporters subsequently adopted social democratic and social federalist ideas. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Georgia became one of the regions of the Russian Empire most susceptible to revolutionary sentiment. Almost all revolutionary parties of the country acted here - from Bolshevik and Menshevik social democrats to communist anarchists and syndicalist anarchists. Natives from Georgia showed revolutionary activity not only in their homeland, but also abroad, many of them achieved wide popularity in the revolutionary movement. Recall that the Georgians or representatives of other peoples living in Georgia were Stalin (Dzhugashvili) and Ordzhonikidze, Japaridze and Kikvidze, Enukidze and Beria, Kalandarishvili and Cherkezov, many other prominent Bolsheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries and anarchists. At the same time, given the specific nature of the mentality of the local population and national traditions, the revolutionary struggle in Georgia almost immediately acquired a radical character. Georgian revolutionaries became famous in the field of expropriations, exchanges with the police, attempts on officials and policemen. It was in Georgia that the proclamation of one of the first in the Russian stories revolutionary peasant republics. This is the Gurian Republic - a little-known, but very interesting page in the political history of the Russian Empire at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Guria - the area of "brave and quick-tempered"

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Guria, a historical region in the southern part of western Georgia, was part of Kutaisi province. It was almost entirely Georgian territory, where immigrants from other regions of the Russian Empire did not move. The center of Guria was the city of Ozurgeti, and Guria itself was called the Ozurgeti uyezd of Kutaisi province. Until 1810, when Guria became part of the Russian Empire, it had the status of an independent principality. For several centuries, after the collapse of the Georgian kingdom, the Gurian principality managed to maintain its independence, although until the 16th century it was formally considered a vassal of the Imeretian kingdom. Guria waged frequent wars with the Ottoman Empire, which attempted to subjugate the southern provinces of the principality, above all Acar - Ajaria. In Guria, the surname Gurieli rules - one of the branches of the Georgian Vdanidze dynasty - Dadiani. In 1810, Prince Mamia V signed an agreement on the transition of the Gurian principality under the protectorate of the Russian Empire, and in 1828, during the reign of Prince David Guriely, the independence of the principality was finally abolished, after which it was incorporated into the Georgian-Imeretian province. In 1846, the city of Guria became part of the Kutaisi province. According to the 1897 census, 90 326 lived in the Ozurgeti Uyezd. Of these, 4 710 people lived in the city of Ozurgeti, and the rest - in smaller settlements. The national composition of the county was, as mentioned above, almost entirely Georgian. 86 057 Georgians lived in Guria, representing 95,27% of the county population, as well as 3 009 Greeks (3,33% of the total population). There were only 526 people in the Ozurgeti County, that is, 0,58% of the total population of the county. The overwhelming majority of Guria’s population was engaged in agriculture, the region as a whole was economically underdeveloped and therefore poor.

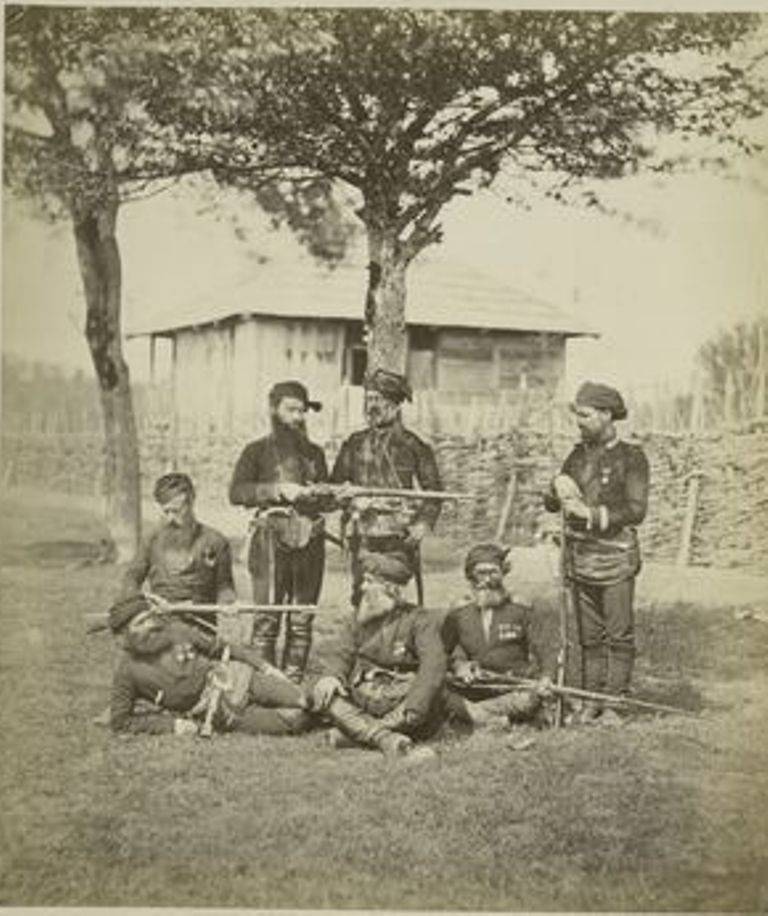

At the same time, the population of Guria had one specific feature that greatly influenced the spread of revolutionary ideas in this region of Georgia - despite the economic backwardness of the county and the poverty of most of the peasant population, the Gurians were very sensitive to education. Ozurgeti district was characterized by a higher level of education compared to other regions of Georgia. The historian and ethnographer of royal origin Vakhushti Bagrationi (1695-1758) described the Gurians (gurueli) as follows: “The Gurian is extremely fast in speech, in movements, in deeds, loves straightforwardness, quickly gets angry, but quickly calms down. The Gurians are smart, fast, and love education” (Vakhushti Bagrationi. History of the Kingdom of Georgia / Translation, preface, dictionary and index: N. T. Nakashidze. - Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1976.). On the other hand, Guria was a land with rich traditions of resistance to the authorities, and the Gurians, in addition to their craving for education, were also distinguished by militancy. In the "Great Encyclopedia" of 1905, the Gurians were described as brave, affable and true to their word, but extremely quick-tempered and irritable. Back in 1840, after the last institution of the Gurian autonomy, the Council of Gurian princes, was abolished in connection with the administrative reform, dissatisfaction with Russian rule began to grow in Guria. It was exacerbated by the introduction of new taxes, as well as rumors that the Gurian peasants would be called up to serve in the Russian army. In May 1841, a popular uprising broke out in the village of Aketi, in which not only peasants, but also nobles and even princes took part. The rebels wanted to break through to the Russian-Turkish border and unite with the troops of the Kobuleti bek Hassan Tavdgiridze. Troops under the command of Colonel Brusilov were thrown against the rebels. However, he failed to defeat the seven thousandth rebel detachments. In August, the detachment of Abes Bolkvadze defeated the Russian detachment near the village of Gogoreti. The rebels then captured the fortress of Shekvetili on the Black Sea coast. Brusilov's detachment, which by this time was able to occupy the capital of Guria Ozurgeti, was under siege. Detachments of the Megrelian Mtavar and the Imereti militia advanced to help Brusilov, who were also defeated by the Gurians. Nevertheless, the approaching reinforcements managed in September 1841 to defeat the rebels. Abesa Bolkvadze was killed, several leaders of the uprising were sent to Siberia. Subsequently, the Gurians were just as brave as they fought against the Russian authorities, fought on its side - during the Russian-Turkish war, in 1876, a volunteer police force of 1 thousand people was to be formed in Guria. However, Guria gave three thousand volunteers, because so many Gurians did not want to show themselves as cowards and were ready to go to war.

Despite the fact that in the interval between 1841 and 1902. there were no serious uprisings in the region, in some places "pirales" continued to operate in Guria. So called local robbers. The word "piraly" comes from a modified Arabic "Firar" - "fluent". Apparently, at first, deserters from the Ottoman army, who were hiding in the Gurian mountains, were so called. Then the name "piraly" received all the local robbers, similar to the North Caucasian abreks. However, the "piraly" observed a kind of "Robin-Gudovsky" code of honor - they did not rob the poor, give part of their booty to the needy and defended their villages from the predatory attacks of other gangs. Most of the time "piraly" was carried out in the mountain forests, but periodically visited the native villages, where they were always welcomed, fed, and, if necessary, provided medical care. By the way, one of the most famous Gurians in the early twentieth century was a certain Datiko Shevardnadze - the uncle of Eduard Shevardnadze, also a native of Guria, who became the foreign minister of the USSR, and then, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the president of independent Georgia.

Seminarians, peasants and the revolutionary movement

After the abolition of serfdom, the majority of Gurian peasants found themselves in an extremely difficult economic situation, without having received land and turned into tenants. Naturally, not being masters of the land they cultivated, they embraced proletarian psychology and were radically inclined towards the existing order. Among the Gurian farmers there were many noblemen who, in terms of wealth and living conditions, did not differ much from the peasants, but had a high level of education and developed self-esteem. Many sons of impoverished nobles received education in Russia, where they perceived radical democratic and socialist ideas. By the way, Philip Ieseevich Makharadze (1868-1941), the future leader of the Georgian SSR, was also a native of the village of Kariskure of the Ozurgeti district. His father, Jesse Mahardze, was a priest, and his son was also about to follow the spiritual path. He graduated from the Ozurgetia Theological School, after which he entered the Tiflis Theological Seminary, but then decided to get a secular specialty. At one time he studied at the Warsaw Veterinary Institute, but did not finish the course and was expelled. After that, Philip Makhardze returned to Georgia, where he engaged in revolutionary activities. By the way, many graduates of the Ozurgetia Theological School participated in the dissemination of revolutionary ideas in Guria. Thus, Gerasim Fomich Makharadze (1881-1937) became one of the leaders of the Guri uprising. His biography is quite typical for a Georgian revolutionary of the early twentieth century. The son of the psalm reader, graduated from the Ozurgeti Theological School on the first category and was recommended to enter the Kutaisi Theological Seminary. However, already in the seminary, Gerasim Makharadze showed free-thinking - he was expelled for six months for organizing a self-education group, but then he was restored. After graduating from the seminary in 1901 Gerasim entered the eastern department of St. Petersburg University. There he joined the Kassa Radicals student group, participated in a demonstration, after which he was arrested for three months and then expelled from the Russian capital. Enrolling in Yurievsky University, Makhardze became a member of the Union Council of united fraternities and organizations, where he represented Georgian students. For participation in the demonstration, he was again arrested for seven months and then expelled to the Caucasus. After that, he went into hiding and under the nickname “Herman” worked first in the Baku Social Democratic underground, and then in Ozurgeti, where he led revolutionary propaganda among Gurian peasantry. George Ilyich Gogelia (1878-1924) was one of the first Georgian and Russian anarchist communists who became interested in revolutionary ideas while studying abroad - in France and Switzerland. He also came from Ozurgeti, who also studied at the Ozurgeti Theological School. It was Gogelia who, in 1900, was one of the initiators of the creation of the Group of Russian Anarchists Abroad, the first association of Russian anarchists created in Switzerland, in Geneva.

Revolutionary ideas lay on the already prepared ground - the peasants of Guria were very unhappy with their socio-economic attitude. Speaking at the II congress of the RSDLP, Mikhail Tskhakaya (1865-1950), a member of the Caucasian Union Committee of the RSDLP, noted that “treasury, princes and clergy belong to vast land areas - forests and mountains, tillage and meadows, pastures and meadows, and the peasant and his to cattle, like poultry, there is no way out of their hut (sakli) and courtyard: everywhere on earth it is “alien” and must pay for pasture, and for forests, etc. ... Add to this: 1) Pawns of priests, besides constant payments from birth to the grave and even after - in the form of an annual fee from each individual family of 2 p assassin (so-called "dram money); 2) Extortion of rural authorities and various officials; 3) Different duties ..." (Third regular congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party 1905 of the year. Full text of the protocols. Gosizdat, M., 1924 g Naturally, the power of the Gurian peasants in such distress could not evoke other feelings than negative ones, since the power in their eyes was personified with the arbitrariness of the landowners and small county officials, the latter were viewed as “the embodiment of evil” for the peasants, to them and presented main claims.

Unrest in the village of Nigoichi

In 1902, fermentation began among the peasants of the village of Nigoichi. In the local school, a teacher worked as a certain George Uratadze - a former student who was expelled because of his political unreliability (Uratadze was a supporter of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party), who raised the question of the position of the local peasantry. Inspired by the speeches of Uratadze, the peasants demanded to reduce the proportion of the crop that was given to the owners of the leased land, establish free access to pastures and give not only the peasants, but also the nobles, the obligation to finance the costs of the village and county budgets. By putting forward demands, the peasants brought a collective oath of allegiance to the struggle and mutual devotion. At the same time, taking an oath, at the request of the Gurians, had to be Uratadze. Soon the former student went to Batumi, where the territorial committee of the Social Democratic Party, closest to Guria, was located. There, Uratadze was going to enlist the support of the Social Democrats and receive further instructions from them on how to act under the circumstances. However, the Social Democrats refused to support the representative of the insurgent village. The most authoritative social democrat of Batumi at this time was Karlo Chkheidze (1864-1926) - inspector of the Batumi municipal hospital, in 1898-1902. held the post of the public Duma of Batumi. Despite the fact that from a young age Chkheidze participated in the revolutionary movement and was twice expelled from the educational institutions - the Novorossiysk University and the Kharkov Veterinary Institute - for participating in student unrest, he occupied fairly moderate positions in the Social Democratic movement. He reacted negatively to the possibility of the Social Democrats supporting the speeches of the peasants of Guria, because there was no industrial proletariat in the county at all, since there were no enterprises in Guria. Therefore, Carlo Chkheidze openly declared to Uratadze: “We are Marxists. Marxism is the philosophy of the proletariat. The peasant, as a small proprietor, is incapable of perceiving the ideology of Marxism. He, like the petty bourgeois, is closer to the bourgeoisie than to the proletariat. Therefore, we cannot put the peasant movement under our banner. ” The Batumi social democrats refused to support the Guri peasants, and Georgiy Uratadze himself was criticized for "petty-bourgeois adventurism."

However, despite the refusal of the Social Democrats to support the performance of the Gurian peasants, the protest movement in Ozurgeti district itself was gaining momentum. Quickly enough, events in the village of Nigoichi were also found in other localities of the county, after which a peculiar political legend about the village in which the landowners won was formed among the peasants. The process of uniting peasants under social slogans began in other villages of the Ozurgetsk district - their inhabitants also put forward demands, accepted a mutual oath of loyalty in the struggle. Naturally, in the conditions of mass protest, most of the landowners did not dare to confront the peasants, and went to meet their demands. The police could not find the instigators of the speeches, because the peasants refused to give out those who were the first to call for taking the oath of allegiance. The movement of the peasants of Guria caused sympathy from the Georgian intelligentsia and even part of the nobility, who saw in it a national liberation struggle against the tsarist regime. In 1903-1905 The Gurian uprising became one of the most important topics discussed by Georgian intellectuals - regardless of their political convictions.

The fame of the events in Guria spread far beyond the county, Georgia and even the Caucasus. Thus, Georgian publicist and public figure Prince Ilya Petrovich Nakashidze (1863-1923) informed about the events in Guria of Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy himself: “I can inform you of the pleasant news: in the Ozurgetsk district, Kutaisi province, among the Gurians (Georgians) peasants, what you wrote in a letter to the working people came true. Last year there were unrest there, and now the peasants refuse to rent landlord’s land and don’t go to the workers for them. Peasants act remarkably unanimously. Landowners are indignant, as if the sacred duty of the peasants, who have now begun to sedit, was to work for them. My uncle, a man quite wealthy, still can not reconcile with the thought, as it was the peasants who dared not to work on his land. Surprisingly, half of the county’s population refused to work with landlords. Suffer poverty, go to work everywhere and stand firm on their own. My dear relative, who is now with us, told me that he had long and vainly sought to hire an employee for his farm, that the noblemen-landlords were left without workers, servants. The population of the Ozurgeti district, Gurians, the same Georgians is only a regional name ... Our people are the most intelligent and susceptible in the South Caucasus. Georgian books and newspapers are most widely distributed there. I will follow and report to you how things will go further ”(I. Nakashidze. Letter to L. N. Tolstoy from April 11 from 1903. Archive of the State Museum of Tolstoy). In turn, the great Russian writer and critic of the state structure of society, Leo Tolstoy closely followed the events in Guria. In one of his diaries, the writer noted: “In the morning there was a cute man Kipiani from Nakashidze, who told miracles about what is happening in the Caucasus: in Guria, Imeretia, Mengrelia, Kakheti. The people decided to be free from the government and get settled themselves. Dusan recorded. It will be necessary to state. This is a great thing. ”

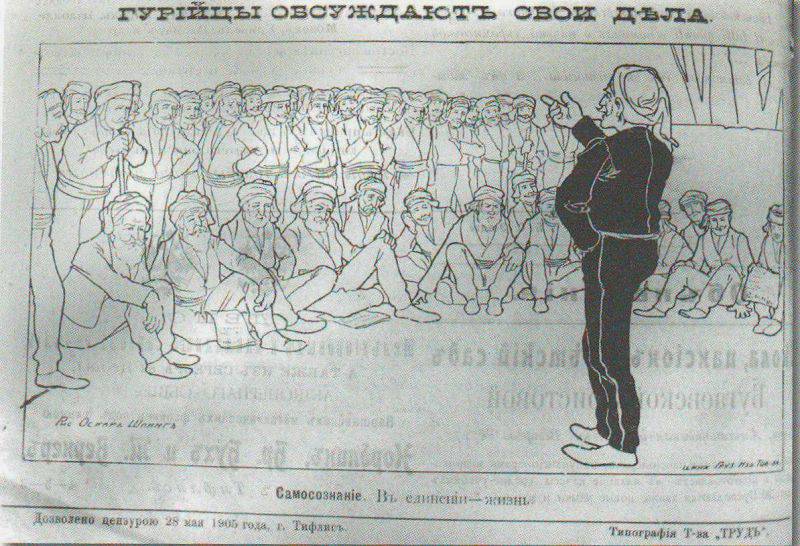

It was about Mikhail Kairakhovich Kipiani (1849-after 1905) - the Georgian revolutionary populist, who spent four years in a Siberian exile and at the time of the events described closely communicated with Ilya Petrovich Nakashidze, and through him - with Leo Tolstoy. Kipiani was very interested in the events in Guria and described them, first of all, as an economic boycott. According to Kipiani, Gurian farmers refused to work for landowners. The actual boycott of power in the county, however, did not mean an increase in crime and delinquency. The peasants agreed not to rob, steal or go to court and the police. Indeed, the number of crimes and delinquencies in the county at that time was significantly reduced, helped by a significant reduction in drunkenness - the peasants consciously decided to drink less and produce less alcohol. To maintain order, ten, Sots, and tysyatskie were chosen from among the peasants, who, in turn, elected three judges for the village. It was decided to discuss important issues at popular gatherings in which up to five thousand people participated. The people's militia was formed - the “Red Hundreds”, who guarded the public order and were supposed to fulfill the tasks of protecting the Gurian villages. The “Red Hundreds” almost did away with the well-known “pirates” (robber) Dato Shevardnadze, but then they decided to pardon him - the “pirates” drew sympathy from many Gurians.

It was about Mikhail Kairakhovich Kipiani (1849-after 1905) - the Georgian revolutionary populist, who spent four years in a Siberian exile and at the time of the events described closely communicated with Ilya Petrovich Nakashidze, and through him - with Leo Tolstoy. Kipiani was very interested in the events in Guria and described them, first of all, as an economic boycott. According to Kipiani, Gurian farmers refused to work for landowners. The actual boycott of power in the county, however, did not mean an increase in crime and delinquency. The peasants agreed not to rob, steal or go to court and the police. Indeed, the number of crimes and delinquencies in the county at that time was significantly reduced, helped by a significant reduction in drunkenness - the peasants consciously decided to drink less and produce less alcohol. To maintain order, ten, Sots, and tysyatskie were chosen from among the peasants, who, in turn, elected three judges for the village. It was decided to discuss important issues at popular gatherings in which up to five thousand people participated. The people's militia was formed - the “Red Hundreds”, who guarded the public order and were supposed to fulfill the tasks of protecting the Gurian villages. The “Red Hundreds” almost did away with the well-known “pirates” (robber) Dato Shevardnadze, but then they decided to pardon him - the “pirates” drew sympathy from many Gurians. Rebellion covers the whole of Guria.

In the end, even the Social Democratic Party, which initially refused to support the peasant uprising, was forced to support it. A committee of agricultural workers was created in Batumi - after discussions, the Social Democratic leaders concluded that the Gurian peasants are not quite typical peasants, because they rent land and are not their owners. That is, with a stretch they fit the definition of the proletariat. Moreover, among the tenants were real industrial workers, the truth is the former, those who were sent to their native villages for participating in the 1902 strike of the year at the Batumi enterprises. It was the former Batumi workers, with experience of participation in the strike and strike movement, spread revolutionary ideas among the peasant population of the county.

In 1903, an independent Social Democratic Committee of Guria was created in the Ozurgeti Uyezd, which soon applied for membership in the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party. This time, the Batumi Social Democrats no longer had any questions, and the Ozurgetian revolutionaries — peasants and rural teachers — were accepted into the ranks of the Social Democratic Party. As it turned out, this was a very correct decision, because by that time the Guria’s Social Democratic Committee had gradually become the only authority in the region. An appeal of the Social Democrats to the “Gurii peasants” was issued, in which the main goals and objectives of the revolutionary struggle were explained as widely as possible. Gurian peasants decided to completely boycott state power, starting from taxes and ending with disobeying the orders of the county administration. As a result of the boycott, the latter almost ceased to exist. The power was the Social Democratic Committee, which proclaimed the introduction of freedom of speech, proceeded to the practice of collecting new rental payments that satisfied the peasants. Thus, the foundations of peasant self-government were laid, which transformed Guriy 1902-1905. in the field of a unique social experiment. Some local feudal lords and officials, of course, tried to oppose the actions of the peasants, but they paid dearly for their actions. Many were expelled from the county or even killed. So, in January 1905, Prince Nakidze was killed, and the grave-diggers of the cemeteries of the county announced a boycott of his funeral, so the prince’s body had to be interred aside outside Guria.

It should be noted that many landowners themselves sympathized with the Gurian peasants, since, evaluating their performance from nationalist positions, they were glad about the awakening of the Georgian people and the development of its democratic traditions. In fact, Guria has turned into a real and almost independent from the central government autonomous republic, living by its laws and trying to build its economy on the principles of social justice, and political life - on the basis of equality. The declaration of equality of rights was accepted even by the Gurian women. Mikhail Kipiani emphasized that Gurian women, like men, attended people's meetings and participated in discussions of issues important for their villages. At meetings, it was said that people should marry for love, not for convenience, so everyone who received a dowry for his wife was offered to return it to their parents. However, parents were allowed to give a dowry directly to the daughters, and if the daughter takes it, then it would not be recognized as immoral.

After the events of January 1905, the revolutionary movement in Guria moved to a new level. Rumors about the beginning of the armed uprising in Russia penetrated into Georgia. The peasants expelled from their villages all the representatives of the royal power, created village communities and formed armed units - the Red Hundreds. By the beginning of February, 1905 was in the hands of insurgent peasants practically the entire territory of Guria. 20 February 1905, a representative of the tsarist administration, informed the center that control of Russian power over the greater territory of Ozurgeti district had been lost. In March, the government was forced to declare 1905 martial law in Kutaisi province, after which military units with a total number of 4 soldiers and officers were sent to Ozurget district. They were commanded by Major General Maksud Alikhanov-Avarsky (000-1846) - Avar by origin, distinguished himself in the Russian-Turkish war and the Central Asian campaigns. However, due to the active resistance of the peasants, the troops of Alikhanov-Avar were forced to retreat. Moreover, the peasants of Imereti, Kakheti and other Georgian regions, who supported the Gurians, began to threaten rebellion if the troops were not withdrawn. The tsarist authorities were forced not only to command General Alikhanov to withdraw troops, but also to make concessions to the rebels. In particular, Prince Golitsyn, who was a Caucasian governor-in-chief and was considered a supporter of the harsh suppression of peasant speeches, was dismissed. Instead, the cavalry general, Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov (1907-1837), famous for his cunning politics, was appointed governor-general of the Caucasus and commander-in-chief of the troops of the Caucasian Military District. Vorontsov-Dashkov was not a supporter of purely violent actions and believed that it was entirely possible to reach an agreement with the peasants by peaceful means.

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Sultan-Crimea-Giray (1836-after 1917) - a Russian nobleman of Crimean-Tatar origin, a descendant of the Crimean khans Gireyev, who had been a member of the Ministry of Finance in the Council of the Commander-in-Chief in the Caucasus, was appointed Deputy Governor Assistant for the Civil Part. Sultan-Crimea-Giray was known as a man of quite liberal views. Historian A.V. Ostrovsky notes that “N. Sultan-Crimea-Giray was directly accused of having connections with some revolutionary leaders in the pre-revolutionary press. We have not yet been able to find concrete and convincing data on this score, but there is reason to say that N. A. Sultan-Crimea-Giray had connections in liberal opposition circles. ” It is obvious that the tsarist government also possessed information about the liberal sympathies of Sultan-Crimea-Giray, since it was he who was assigned to negotiate with the Gurian peasants. A descendant of the Crimean Khans was sent to Guria, where he conducted surveys of the local peasant population and spoke at meetings of rural residents. In turn, the peasants made a list of requirements and transferred it to the Crimea-Giray. Liberal authorities allowed the peasants to create self-government bodies, open schools and libraries in the villages.

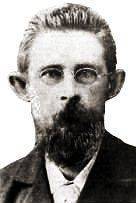

It is noteworthy that the events in Guria caused informal support from the regional authorities in the face of the Kutaisi governor. It was explained very simply. In July, 1905, the governor of the Kutaisi province, which included Ozurgeti district, was appointed Vladimir Aleksandrovich Staroselsky (1860-1916) - a Russian agronomist, a graduate of Petrovsky Agricultural Academy. He was a personal friend of Count Illarion Vorontsov-Dashkov (1837-1916). It was Vorontsov-Dashkov who assisted the talented agronomist Staroselsky in his appointment to the governorship. However, Staroselsky was in no hurry to suppress the uprising by force, since he himself was sympathetic to social democratic ideas (in 1907, he joined the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (Bolsheviks)). The Kutaisi Governor visited the villages of Guria, accompanied by the Gurian peasant militia, and took a neutral position, without interfering with the development of events in the district.

Soon, under the patronage of the governor in Kutaisi, several leftist organizations emerged, including the union and the bureau of revolutionary teachers. In fact, being at the post of governor, Staroselsky contributed to the revolutionary movement in Kutaisi province, for which he caused a sharply negative attitude towards himself from the central government. In principle, there was nothing surprising in the appointments of Sultan-Crimea-Girey and Staroselsky, since the governor himself, Count Vorontsov-Dashkov, held relatively liberal positions. At least, this is how Sergey Yulievich Vitte recalls about him: “Gr. Vorontsov-Dashkov was and still remains a man of a rather liberal direction; to some extent, he selected such employees for himself ”(Witte S. Yu. 1849 — 1894: Childhood. The Reign of Alexander II and Alexander III, Chapter 15 // Memoirs. - M .: Sotsekgiz, 1960). When in November 1905 in Tiflis began clashes between the Armenian and Azerbaijani population of the city, the Social Democrats appealed to the governor Vorontsov-Dashkov with a request to provide the workers weapon to maintain public order and appease the parties to the conflict, as well as to send "conscious soldiers" to help the workers' detachments. Despite the protests of officers and officials, Vorontsov-Dashkov decided to satisfy the request of the Social Democrats and 25 in November local organizations of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party were issued 500 guns, which were distributed according to party lists.

Soon, under the patronage of the governor in Kutaisi, several leftist organizations emerged, including the union and the bureau of revolutionary teachers. In fact, being at the post of governor, Staroselsky contributed to the revolutionary movement in Kutaisi province, for which he caused a sharply negative attitude towards himself from the central government. In principle, there was nothing surprising in the appointments of Sultan-Crimea-Girey and Staroselsky, since the governor himself, Count Vorontsov-Dashkov, held relatively liberal positions. At least, this is how Sergey Yulievich Vitte recalls about him: “Gr. Vorontsov-Dashkov was and still remains a man of a rather liberal direction; to some extent, he selected such employees for himself ”(Witte S. Yu. 1849 — 1894: Childhood. The Reign of Alexander II and Alexander III, Chapter 15 // Memoirs. - M .: Sotsekgiz, 1960). When in November 1905 in Tiflis began clashes between the Armenian and Azerbaijani population of the city, the Social Democrats appealed to the governor Vorontsov-Dashkov with a request to provide the workers weapon to maintain public order and appease the parties to the conflict, as well as to send "conscious soldiers" to help the workers' detachments. Despite the protests of officers and officials, Vorontsov-Dashkov decided to satisfy the request of the Social Democrats and 25 in November local organizations of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party were issued 500 guns, which were distributed according to party lists. As the political situation in the country worsened, the revolutionary movement in Ozurgeti uyezd of Kutaisi province became radicalized. In October 1905, the Gurian peasants defeated a detachment of the district head Lazarenko, who was trying to restore power in the region and destroyed the railway lines along which government troops could be transferred to Guria. A large number of guards and officials were also killed. In November 1905, the peasant "Red Hundreds" entered the county center - the city of Ozurgeti. They captured the mail, telephone and telegraph. Having occupied Ozurgeti, the rebels proclaimed the creation of the Gurian Republic. After this, the royal authorities could not tolerate an “anarchy” in the Ozurgeti district. Moreover, the "red plague" has spread from Guria to other parts of Georgia. The example of Guria was followed by several more regions of Georgia, where republics of the Gurian type were also proclaimed.

The defeat of the uprising and the fate of key figures

Impressive military forces under the command of Major General Alikhanov-Avarsky and Colonel Krylov were sent to suppress the peasant uprising in Guria. By 10 January 1906, the main centers of the uprising in the territory of Ozurgeti County were suppressed. Learning about the activities of the Kutaisi governor Vladimir Staroselsky, Emperor Nicholas II remarked: “I consider it necessary to say a strong word about someone - this is about the Kutaisi governor Staroselsky. According to all the information I received, he is a real revolutionary ... ". By order of the central government, General Alikhanov-Avarsky, who commanded the pacification of Georgia, arrested Vladimir Staroselsky and the vice-governor of the Kutaisi province of Knishidze and sent them to Tiflis. Staroselsky was dismissed from the post of governor and expelled from Tiflis to the Kuban. 2 April 1906 was liberated from the duties of an assistant governor in the Caucasus for the civil part of the liberal-minded Nikolai Alexandrovich Sultan-Crimea-Giray. Incidentally, Count Illarion Vorontsov-Dashkov kept the post of governor in the Caucasus and occupied him for another ten years - until August 1915, after which he was replaced by Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich (junior).

Impressive military forces under the command of Major General Alikhanov-Avarsky and Colonel Krylov were sent to suppress the peasant uprising in Guria. By 10 January 1906, the main centers of the uprising in the territory of Ozurgeti County were suppressed. Learning about the activities of the Kutaisi governor Vladimir Staroselsky, Emperor Nicholas II remarked: “I consider it necessary to say a strong word about someone - this is about the Kutaisi governor Staroselsky. According to all the information I received, he is a real revolutionary ... ". By order of the central government, General Alikhanov-Avarsky, who commanded the pacification of Georgia, arrested Vladimir Staroselsky and the vice-governor of the Kutaisi province of Knishidze and sent them to Tiflis. Staroselsky was dismissed from the post of governor and expelled from Tiflis to the Kuban. 2 April 1906 was liberated from the duties of an assistant governor in the Caucasus for the civil part of the liberal-minded Nikolai Alexandrovich Sultan-Crimea-Giray. Incidentally, Count Illarion Vorontsov-Dashkov kept the post of governor in the Caucasus and occupied him for another ten years - until August 1915, after which he was replaced by Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich (junior). General Alikhanov - Avarsky was appointed interim governor of the Kutaisi province. Alikhanov's detachments, consisting of Cossacks and Highlanders, brutally cracked down on the peasants who participated in the uprising. A number of villages were burned, and their inhabitants evicted. Over 300 members of the Guri uprising were arrested and sent into exile in Siberia. Subsequently, already in the years of the Civil War, it was from the veterans of the Georgian “Red Hundreds” in Eastern Siberia that the backbone of the famous partisan detachment of the anarchist Nestor Kalandarishvili - “Siberian Old Man”, as his colleagues called him, was formed. By the way, Nestor Kalandarishvili himself and his closest associates, Mikhail Asatiani, Iosif Kiguradze, Gerasim Zoidze, were participants in the Guriysky uprising and fought in the “red hundreds”. As for Vladimir Alexandrovich Staroselsky, he settled in Ekaterinodar (now Krasnodar), where he engaged in revolutionary activities — he became secretary of the Kuban regional committee of the RSDLP, then chairman of the North Caucasus Allied Committee of the RSDLP. In 1908, the gendarmes were going to arrest Staroselsky, but during a search in his apartment in Ekaterinodar they found letters from Vorontsov-Dashkova, after which they hesitated and waited some time for the leadership to give further instructions to arrest or not to touch the Tsar’s personal friend. While the trial was under way, Vladimir Staroselsky managed to leave the Russian Empire. He settled in Paris, where the rest of his life worked as a photographer and participated in the activities of the Paris organization of Russian Bolsheviks - political emigrants.

As for General Alikhanov-Avarsky, a year after the suppression of the Guri uprising, he was overtaken by revolutionaries. At the beginning of 1907, Alikhanov, promoted to lieutenant general, was appointed commander of the 2 Caucasian Cossack Division, and on July 3 1907 in Alexandropol (now Gyumri) two bombs were thrown at his crew. General Alikhanov died. As it turned out, the attack on the division commander was organized by members of the Dashnaktsutyun party, who avenged the actions of the general during the suppression of the uprising in the Erivan province. Then Alikhanov openly patronized his relatives, the Khans of Nakhichevan (he was married to Zarin-Taj Begum of Nakhichevan, the daughter of Major-General Kelbali Khan Nakhichevan), who had cruelly punished the insurgent Armenian population.

The Gurian Republic entered Russian history as a unique example of the self-organization of the peasant population in the peripheral region of the country. Despite the actual absence of centralized leadership, any organizational structures of the party type, the Gurian peasants managed to form grassroots self-government bodies and over the course of several years, gradually achieve their goals.

Information