Gas attack king

As the Russian army mastered the chemical weapon and sought salvation from him

The widespread use of Germany on the fronts of the Great War of poisonous gases forced the Russian command to also enter the race of chemical weapons. In this case, it was necessary to urgently solve two problems: first, to find a way to protect against new weapons, and secondly, “not to remain indebted to the Germans,” and answer them the same. With both the Russian army and industry coped more than successfully. Thanks to the outstanding Russian chemist Nikolai Zelinsky, already in 1915, the world's first universal effective gas mask was created. In the spring of 1916, the Russian army conducted its first successful gas attack. At the same time, by the way, no one in Russia was particularly worried about the “inhuman” nature of this type of weapon, and the command, noting its high efficiency, directly urged the troops “to use the production of asphyxiated gases more often and more intensively”. (About stories the emergence and first experiences of the use of chemical weapons on the fronts of the First World War, read in the previous article heading.)

Empire needs poison

Before responding to the German gas attacks with the same weapon, the Russian army had to organize its production from scratch. Initially, the production of liquid chlorine was created, which before the war was completely imported from abroad.

This gas began to be supplied by pre-war and converted production — four plants in Samara, several enterprises in Saratov, and one plant each at Vyatka and in the Donbas in Slavyansk. In August 1915, the army received the first 2 tons of chlorine, a year later, by the autumn of 1916, the production of this gas reached 9 tons per day.

An indicative story took place with the plant in Slavyansk. It was created at the very beginning of the 20th century for the production of bleach by electrolytic method from rock salt mined in local salt mines. That is why the plant was called "Russian Electron", although 90% of its shares belonged to the citizens of France.

In 1915, it was the only production located relatively close to the front and theoretically capable of quickly producing chlorine on an industrial scale. Having received subsidies from the Russian government, the plant over the summer of 1915 did not give the front a single ton of chlorine, and at the end of August the management of the plant was transferred to the military authorities.

Diplomats and newspapers seemed to be allied France immediately raised a fuss about the violation of the interests of French owners in Russia. The tsarist authorities feared to quarrel with the Allies on the Entente, and in January 1916, the management of the plant was returned to the previous administration and even provided new loans. But until the end of the war, the plant in Slavyansk did not go for the release of chlorine in quantities stipulated by military contracts.

The attempt to obtain phosgene from private industry in Russia also failed: Russian capitalists, in spite of all their patriotism, inflated prices and, due to the lack of sufficient industrial capacities, could not guarantee timely fulfillment of orders. For these needs, it was necessary to create from scratch new state production.

Already in July, 1915, the construction of a “military chemical plant” began in the village of Globino on the territory of the present Poltava region of Ukraine. Initially they planned to start producing chlorine there, but in the fall it was reoriented to new, more lethal gases, phosgene and chloropicrin. The ready-made infrastructure of the local sugar factory, one of the largest in the Russian Empire, was used for the plant of military chemistry. Technical backwardness led to the fact that the enterprise was built for more than a year, and Globinsky Military Chemical Plant began production of phosgene and chloropicrin only on the eve of the February 1917 revolution of the year.

The situation was similar with the construction of the second large state enterprise for the production of chemical weapons, which they began to build on March 1916 in Kazan. The first phosgene "Kazan Military Chemical Plant" was released in 1917 year.

Initially, the Ministry of War intended to organize large chemical plants in Finland, where there was an industrial base for such production. But the bureaucratic correspondence on this issue with the Finnish Senate dragged on for many months, and by 1917 the “military chemical plants” in Varkaus and Kayaan were not ready.

In the meantime, state-owned plants were only being built, the military ministry had to buy gases wherever possible. For example, 21 in November 1915, the 60 of thousands of pounds of liquid chlorine, was ordered from Saratov City Government.

"Chemical Committee"

From October 1915, the first “special chemical teams” began to form in the Russian army to carry out gas cylinder attacks. But due to the initial weakness of the Russian industry, the Germans did not succeed in attacking the Germans with a new “poisonous” weapon in the 1915 year.

To better coordinate all efforts to develop and produce combat gases in the spring of 1916, the Chemical Committee was created under the General Artillery Directorate of the General Staff, often simply referred to as the “Chemical Committee”. He was subordinated to all existing and established chemical weapons plants and all other work in this area.

The Chairman of the Chemical Committee was 48-year-old Major-General Vladimir Nikolaevich Ipatiev. A prominent scientist, he had not only a military, but also a professorial rank. Before the war, he read chemistry courses at St. Petersburg University.

The first meeting of the Chemical Committee was held on 19 on May 1916 of the year. Its composition was heterogeneous - one lieutenant general, six major generals, four colonels, three state councilors and one titular officer, two process engineers, two professors, one academician and one ensign. The rank of ensign was a military scientist Nestor Samsonovich Puzhay, a specialist in explosives and chemistry, appointed "the ruler of the office of the Chemical Committee". It is curious that all decisions of the committee were taken by vote; in the case of equality, the vote of the chairman became decisive. Unlike other organs of the General Staff, the Chemical Committee had the maximum autonomy and autonomy, which can only be in a belligerent army.

The local chemical industry and all work in this area were managed by eight district “sulfuric acid bureaus” (as they were called in the documents of those years) - the entire territory of the European part of Russia was divided into eight subordinate bureau areas: Petrogradsky, Moscow, Upper Volga, Middle Volga , Ural, Caucasian and Donetsk. It is significant that the Moscow Bureau was headed by the engineer of the French military mission Frossard.

Work in the Chemical Committee was well paid. The chairman, in addition to all military payments for the rank of general, received another 450 rubles monthly, and the department heads received 300 rubles. The other members of the additional remuneration committee were not supposed to, but for each meeting they made a special payment in the amount of 15 rubles each. For comparison, the rank and file of the Russian Imperial Army then received 75 kopecks per month.

In general, the Chemical Committee was able to cope with the initial weakness of the Russian industry and by the autumn of 1916, it started producing gas weapons. By November, 3 180 tons of toxic substances were produced, and the program for the next 1917 year was planned to bring the monthly productivity of toxic substances to 600 tons in January and to 1 300 tons - in May.

“We should not remain indebted to the Germans”

For the first time, Russian chemical weapons were used on 21 March 1916 of the year when they were attacked by Lake Naroch (on the territory of the modern Minsk region). During the artillery preparation, the Russian guns fired 10 thousands of shells with suffocating and poisonous gases on the enemy. This amount of shells was not enough to create a sufficient concentration of toxic substances, and the losses of the Germans were insignificant. But, nevertheless, the Russian chemistry frightened them and made them stop counterattacks.

In the same offensive, it was planned to conduct the first Russian "gas balloon" attack. However, it was canceled due to rain and fog - the effectiveness of the chlorine cloud depended critically not only on the wind, but also on the temperature and humidity of the air. Therefore, the first Russian gas attack with the use of chlorine cylinders was made on the same sector of the front later. Two thousand cylinders began gas release on July 19 1916 of the year. However, when two Russian companies attempted to attack the trenches of the Germans, through which the gas cloud had already passed, they were met by rifle and machine-gun fire - as it turned out, the enemy did not suffer serious losses. Chemical weapons, like any other, required experience and skill for their successful use.

In total for the 1916 year, the “chemical teams” of the Russian army produced nine large gas attacks, using 202 tons of chlorine. The first successful gas attack by the Russian troops took place in early September 1916. This was a response to the summer gas attacks of the Germans, when, in particular, at the Belarusian city of Smorgon on the night of 20 July, 3846 soldiers and officers of the Grenadier Caucasus Division were poisoned with gas.

In August 1916, the commander-in-chief of the Western Front, General Alexei Evert (by the way, from the Russified Germans) issued an order: “Recently, the Germans launched two gas attacks, which, mainly due to their duration (from 2 to 6 hours), caused significant losses. Having the means necessary for the production of gas attacks, one should not remain indebted to the Germans, why I order to make wider use of the active activities of chemical teams, more often and more intensively using the release of asphyxiating gases according to the enemy's position. ”

Fulfilling this order, on the night of September 6, 1916, of the 3 of the 30 hour of minutes, there was a gas attack on the front about a kilometer from the Russian troops. 500 large and 1700 small cylinders filled with 33 tons of chlorine were used.

However, after 12 minutes, an unexpected gust of wind carried part of the gas cloud into the Russian trenches. At the same time, the Germans also managed to react quickly, noticing the chlorine cloud moving in the dark after 3 minutes after the start of the release of gases. The return fire of German mortars in the Russian trenches was broken 6 gas cylinders. The concentration of escaping gas in the trench was so great that the Russian soldiers who were nearby had tires burst into gas masks. As a result, the gas attack was stopped after 15 minutes after the start.

However, the result of the first mass use of gases was estimated by the Russian command highly, since the German soldiers in the advanced trenches suffered sensitive losses. The chemical shells used that night by the Russian artillery, which quickly silenced the German batteries, rated even higher.

In general, since 1916, all participants in the First World War began to gradually abandon the "gas balloon" attacks and move on to the massive use of artillery shells with lethal chemistry. The release of gas from cylinders completely depended on the favorable wind, while the firing of chemical shells made it possible to unexpectedly attack the enemy with poisonous gases, regardless of weather conditions and at a greater depth.

From 1916, Russian artillery began to receive 76-mm gas shells or, as they were then officially called, “chemical grenades”. Some of these projectiles were filled with chloropicrin, a very strong tear gas, and some with deadly phosgene and hydrocyanic acid. By the autumn of 1916, 15 of thousands of such shells were sent to the front every month.

On the eve of the February 1917 revolution, chemical shells for heavy 152-millimeter howitzers began to be sent to the front for the first time, and in the spring - chemical ammunition for mortars. In the spring of 1917, the infantry of the Russian army received the first 100 of thousands of hand chemical grenades. In addition, they began the first experiments on the creation of jet rockets with gas. Then they did not give an acceptable result, but it was from them that the famous “Katyusha” would be born already in Soviet times.

Due to the weakness of the industrial base, the army of the Russian Empire was never able to match either the enemy or the Allies in the “Entente” in the number and “assortment” of chemical projectiles. In total, Russian artillery received less than 2 million chemical shells, while, for example, France produced over 10 million such shells during the war years. When the United States entered the war, by November their powerful industry 1918 produced almost 1,5 a million chemical shells every month - that is, in two months it produced more than all of tsarist Russia could in two years of war.

Gas mask with ducal monograms

The first gas attacks immediately demanded not only the creation of chemical weapons, but also means of protection from them. In April, 1915, preparing for the first use of chlorine under Ypres, the German command supplied its soldiers with cotton wool pads soaked in sodium hyposulfite solution. They had to close their nose and mouth during the start-up of gases.

By the summer of that year, all the soldiers of the German, French and British armies were equipped with cotton gauze bandages impregnated with various chlorine neutralizers. However, such primitive gas masks turned out to be inconvenient and unreliable, besides softening the damage with chlorine, they did not provide protection against more toxic phosgene.

In Russia, such dressings in the summer of 1915, were called “snout masks”. They were made for the front by various organizations and individuals. But as the German gas attacks showed, they almost did not save them from the massive and prolonged use of toxic substances, and they were extremely inconvenient in circulation - they quickly dried out, completely losing their protective properties.

In August, 1915, a professor at Moscow University, Nikolai Dmitrievich Zelinsky, suggested using activated charcoal as a means to absorb poisonous gases. Already in November, Zelinsky’s first coal mask was tested for the first time complete with a rubber helmet with glass “eyes”, which was made by an engineer from St. Petersburg, Mikhail Kummant.

Unlike previous designs, this turned out to be reliable, convenient to use and ready for immediate use for many months. The received protective device successfully passed all the tests and was named the “Zelinsky-Kummant gas mask”. However, here the obstacles for the successful arming of the Russian army with them were not even the flaws of Russian industry, but the departmental interests and ambitions of the officials.

At that time, all work on chemical weapons protection was assigned to the Russian general and German prince Friedrich (Alexander Petrovich) of Oldenburg, a relative of the ruling Romanov dynasty, who held the position of the Supreme Head of the Imperial Army Sanitary and Evacuation Unit. The prince at that time was almost 70 years old and he was remembered by Russian society as the founder of the resort in Gagra and a fighter against homosexuality in the guard.

The prince actively lobbied for the adoption and production of a gas mask, which was designed by teachers of the Petrograd Mining Institute using experience in the mines. This gas mask, which was called the “gas mask of the Mining Institute,” as tests showed, was less protective of asphyxiating gases and it was harder to breathe in it than in the Zelinsky-Kummant gas mask. Despite this, the Prince of Oldenburg instructed to begin the production of 6 millions of “gas masks from the Mining Institute”, decorated with his personal monogram. As a result, the Russian industry has spent several months on the release of a less sophisticated design.

19 March 1916 at a meeting of the Special Conference on Defense - the main body of the Russian empire for managing the military industry - sounded an alarming report on the front with “masks” (as gas masks were then called): “The masks of the simplest type are poorly protected from chlorine, but not at all protect from other gases. Masks of the Mining Institute are unsuitable. The production of Zelinsky’s masks, long recognized as the best, has not been established, which should be considered to be criminal negligence. ”

As a result, only the joint opinion of the military allowed the start of mass production of Zelinsky’s gas masks. March 25 appeared the first state order for 3 million and the next day another 800 thousand gas masks of this type. By April 5 already made the first batch of thousands in 17.

However, until the summer of 1916, the release of gas masks remained extremely inadequate - in June, no more than 10 thousand units per day were sent to the front, while millions of them were required for reliable protection of the army. Only the efforts of the Chemical Commission of the General Staff allowed by the autumn to radically improve the situation - by the beginning of October 1916 had sent over 4 millions of different gas masks to the front, including 2,7 million "Zelinsky-Kummant gas masks".

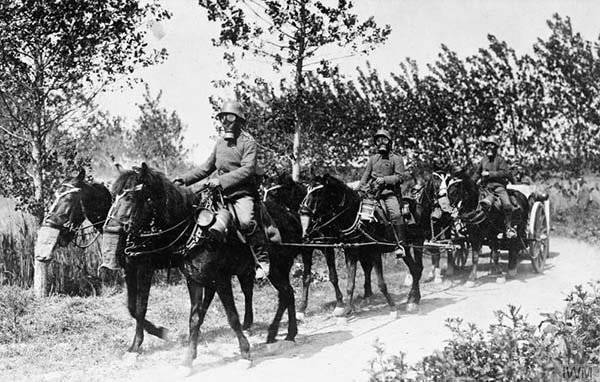

In addition to gas masks for people during the First World War, they had to attend to special gas masks for horses, which then remained the main force of the army, not to mention the numerous cavalry. Until the end of 1916, 410 thousands of horse gas masks of various designs arrived at the front.

Over the years of the First World War, the Russian army received over 28 million gas masks of various types, of which over 11 million Zelinsky-Kummant system. Since the spring of the 1917, only they were used in the combat units of the army, so the Germans refused to use “gas balloon” attacks with chlorine on the Russian front because of their total inefficiency against the troops in such gas masks.

"The war crossed the last line"

According to historians, during the First World War, about 1,3 million people suffered from chemical weapons. The most famous of them, perhaps, was Adolf Hitler - October 15 1918, he was poisoned and temporarily lost his sight as a result of the close rupture of a chemical projectile.

It is known that for the year 1918, from January to the end of the fighting in November, the British lost the soldier from the 115 764 chemical weapons. Of these, less than one tenth percent died - 993. Such a small percentage of fatal gas losses is associated with the complete equipping of troops with perfect types of gas masks. However, a large number of wounded, or rather poisoned and lost combat effectiveness, left chemical weapons a formidable force in the fields of the First World War.

The US Army entered the war only in the 1918 year, when the Germans brought the use of various chemical projectiles to the maximum and perfection. Therefore, among all the losses of the American army, over a quarter accounted for chemical weapons.

This weapon not only killed and wounded - with the massive and long-term use, it rendered whole divisions temporarily inefficient. Thus, during the last offensive of the German army in March 1918 of the year, with artillery preparation, 3 of thousands of shells with mustard gas were fired against the 250 of the British army alone. British soldiers on the front line had to wear gas masks continuously for a week, which made them almost unusable.

The losses of the Russian army from chemical weapons in World War I are estimated with a wide range. During the war, these figures, for obvious reasons, were not announced, and the two revolutions and the collapse of the front by the end of 1917, led to significant gaps in statistics. The first official figures were published already in Soviet Russia in the 1920 year - 58 890 poisoned non-fatal and 6268 dead from gases. Hot on the heels of the 20-30-ies of the XX century, studies in the West led to much larger numbers - over 56 thousands killed and about 420 thousands poisoned.

Although the use of chemical weapons did not lead to strategic consequences, but its impact on the psyche of the soldiers was significant. Sociologist and philosopher Fyodor Stepun (by the way, himself of German origin, his real name is Friedrich Steppuhn) served as a junior officer in Russian artillery. During the war, in 1917, his book “From the letters of ensign artilleryman” was published, where he described the horror of people who survived the gas attack:

“Night, darkness, overheads howl, splashing shells and the whistle of heavy shards. Breathing is so hard that it seems to be suffocating. The masked voices are almost inaudible, and in order for the battery to accept the command, the officer needs to shout it right in the ear to each gun gunner. At the same time, the terrible unrecognizability of the people around you, the loneliness of the damned tragic masquerade: white rubber skulls, square glass eyes, long green trunks. And all in a fantastic red sparkling gaps and shots. And above all, the insane fear of severe, disgusting death: the Germans shot five hours, and the masks were designed for six.

You can't hide, you have to work. With each step it hurts the lungs, overturns backwards and the feeling of suffocation increases. And you need not only walk, you have to run. Perhaps, the horror of the gases is not characterized by anything as vividly as by the fact that no one in the gas cloud paid any attention to the shelling, but the shelling was terrible - more than a thousand shells fell on our battery alone ...

In the morning, upon the cessation of the shelling, the sight of the battery was terrible. In the dawn fog people are like shadows: pale, with bloodshot eyes, and with coal gas masks settled on the eyelids and around the mouth; many are sick, many are swooning, the horses are all lying on the end of the line with dull eyes, bloody foam at the mouth and nostrils, some are struggling with convulsions, some have already died. ”

Fyodor Stepun summarized these experiences and impressions of chemical weapons: “After the gas attack in the battery, everyone felt that the war had crossed the last line, that from now on everything was allowed to her and nothing was sacred.”

Information