Was the Crimean War inevitable?

Today, when Russia remains in a situation of strategic choice, reflections on historical alternatives are becoming especially topical. They, of course, do not insure us against mistakes, but they still leave hope for the absence of initially programmed outcomes in history, and therefore in modern life. This message inspires by the ability to avoid the worst with will and reason. But he also worries about the existence of the same chances to turn to a disastrous path if the will and reason refuse politicians who make fateful decisions.

The Eastern crisis of 50 in the history of the international relations of the XIX century occupies a special place, being a kind of “dress rehearsal” for the future imperialist division of the world. The end of the almost 40-year era of relative stability in Europe has come. The Crimean War (in a certain sense, “world”) was preceded by a rather long period of complex and uneven development of international contradictions with alternating phases of ups and downs. After the fact: the origin of the war looks like a long ripened conflict of interests, with inexorable logic approaching a logical outcome.

Milestones such as the Adrianople (1829) and Unkiar-Iskelesiysky (1833) treaties, the incident with “Vixen” (1836 - 1837), the London 1840 - 1841 conventions, the king’s visit to England to 1844, the 1848-1849 European revolutions with their immediate consequences for the “Eastern Question” and finally the prologue of a military confrontation is a dispute over “holy places” that prompted Nicholas I to new confidential explanations with London, which in many ways unexpectedly complicated the situation.

Meanwhile, in the eastern crisis of the 1850s, as many historians believe, there was no inherent predestination. They suggest that for quite a long time there were fairly high chances of preventing both the Russian-Turkish war and (when it did not happen) the Russian-European one. Opinions differ only in identifying an event that turned out to be a “point of no return”.

This is really a curious question. In itself, the beginning of the war between Russia and Turkey [1] did not constitute a catastrophe, or even a threat to peace in Europe. According to some researchers, Russia would have limited itself to “symbolic bloodletting,” after which it would allow the European “concert” to intervene to work out a peace treaty. In the autumn and winter of 1853, Nicholas I probably expected just such a development of events, hoping that historical experience does not give reason to fear a local war with the Turks on the pattern of the previous ones. When the king accepted the challenge of Porta, the first to start fighting, he had no choice but to fight. The management of the situation has almost completely passed into the hands of the Western powers and Austria. Now only the choice of the further scenario depended on them - either localization or escalation of war.

The notorious “point of no return” can be searched in different places of the event-chronological scale, but as soon as it was finally passed, the whole pre-history of the Crimean War takes on a different meaning, providing the supporters of the theory of regularities with arguments that, despite their deficiency, are easier to accept than to disprove. It cannot be proved with absolute certainty, but it can be assumed that much of what happened on the eve of the war and two to three decades before was due to deep-seated processes and trends in world politics, including the Russian-British contradictions in the Caucasus, which markedly increased the overall tension in the Middle East .

The Crimean War did not arise because of the Caucasus (however, it is difficult to point out at all exactly a specific reason). But hopes for engaging this region in the sphere of the political and economic influence of England gave the ruling class of the country an underlying incentive if not to purposefully unleash a war, then at least to abandon excessive efforts to prevent it. The temptation to find out what can be won from Russia to the east (as well as to the west) from the straits was considerable. Perhaps you should listen to the opinion of one English historian who considered the Crimean War largely the product of the “big game” in Asia.

Emperor Napoleon III

A separate issue is the very difficult question of the responsibility of Napoleon III, in which many historians see its main instigator. Is it so? Yes and no. On the one hand, Napoleon III was a consistent revisionist in relation to the Vienna system and its fundamental principle - the status quo. In this sense, the Nikolaev Russia — the guardian of the “rest in Europe” —for the French emperor was the most serious obstacle that required removal. On the other hand, it’s not at all the fact that he was going to do this with the help of a big European war that would create a risky and unpredictable situation, including for France itself.

Intentionally provoking a dispute about the “holy places”, Napoleon III, perhaps, would like nothing more than a diplomatic victory that allowed him to sow discord among the great powers, primarily on the question of the expediency of maintaining the status quo in Europe. Drama, however, is different: he was unable to keep control over the course of events and gave the Turks hands on the levers of dangerous crisis manipulation in their own, far from peace-loving interests. The actual Russian-Turkish contradictions were also important. Port has not abandoned claims to the Caucasus.

The confluence of unfavorable circumstances for Russia at the beginning of the 1850s was determined not only by objective factors. The unmistakable policy of Nicholas I accelerated the formation of the European coalition directed against him. By provoking and then deftly using the tsar’s miscalculations and delusions, the London and Paris offices voluntarily or unwittingly created the prerequisites for an armed clash. Responsibility for the Crimean drama was fully shared with the Russian monarch by the Western governments and the Port, which sought to weaken Russia's international position and deprive it of the advantage it received as a result of the Vienna agreements.

Portrait of Emperor Nicholas I

A certain share of the blame lies with the partners of Nicholas I in the Holy Alliance - Austria and Prussia. In September, the Russian emperor held confidential talks with Franz Joseph I and Friedrich Wilhelm IV in Olmütz and Warsaw in September 1853. The atmosphere of these meetings, according to contemporaries, did not leave any doubts: “the closest friendship reigned between the participants”. Willingly or unwittingly, the Austrian emperor and the Prussian king helped Nicholas I to establish himself firmly in the hope of loyalty to his ancestral allies. At least for the assumptions that Vienna "will surprise the world with its ingratitude," and Berlin will not take the side of the king, there was no reason.

The ideological and political solidarity of the three monarchs, which separated them from the “democratic” West (England and France), was not an empty sound. Russia, Austria and Prussia were interested in preserving the domestic (“moral”) and international (geopolitical) status quo in Europe. Nicholas I remained the most real guarantor of his; therefore, in the hope of the tsar for the support of Vienna and Berlin, there was not that much idealism.

Another thing is that, apart from ideological interests, Austria and Prussia were geopolitical. This put Vienna and Berlin on the eve of the Crimean War before the difficult choice between the temptation to join the coalition of winners to get a share of trophies and the fear of losing in the face of an overly weakened Russia defensive stronghold against the revolution. The material finally got the better of the ideal. Such a victory was not fatally predetermined, and only a brilliant politician could foresee it. Nicholas I did not belong to this category. This is perhaps the most important and perhaps the only thing in which he is guilty.

It is more difficult to analyze the Russian-English contradictions in the 1840-s, more precisely - their perception of Nicholas I. It is considered that he underestimated these contradictions, and exaggerated the Anglo-French. It seems that he really did not notice that under the cover of an imaginary alliance with Russia in the "Eastern Question" (London conventions, 1840 - 1841) Palmerston was nurturing the idea of a coalition war against her. Nicholas I did not notice (in any case, did not give it his due) and the process of rapprochement between England and France, which began to emerge from the middle of the 1840s.

Nicholas I, in a sense, lost the Crimean War already in 1841, when he made a political miscalculation because of his self-assured idealism. Relatively easy going to the rejection of the benefits of the Treaty of Iskélese, the king naively expected to receive in return for today's concession the British tomorrow to share the eventual "Ottoman inheritance."

In 1854, it became clear that this was a mistake. However, in essence, it turned into a mistake only because of the Crimean War - that “strange” one, which, according to many historians, unexpectedly arose from the fatal plexus of half-random, not inevitable circumstances. In any case, at the time of the signing of the London Convention (1841) there was no visible reason to believe that Nicholas I condemned himself to a collision with England, and they certainly would not have appeared if in 1854 a year there had been a whole bunch of factors caused by fear, suspicion, ignorance, miscalculations, intrigues and vanity did not result in a coalition war against Russia.

It turns out a very paradoxical picture: the events of 1840-x - the beginning of 1850-s with their low level of conflict potential “logically” and “naturally” led to a big war, and a series of dangerous crises, revolutions and military alarms of 1830-x (1830 - 1833, 1837 , 1839 - 1840) illogical and irregularly ended with a long period of stabilization.

There are historians who claim that Nicholas I was completely sincere when he tirelessly convinced England of his lack of anti-British intentions. The king wanted to create an atmosphere of personal trust between the leaders of both states. Despite all the difficulties of their achievement, Russian-English compromise agreements on ways to resolve the two Eastern crises (1820-s and the end of 1830-s) proved to be productive in terms of preventing a major European war. Having no experience of such cooperation, Nicholas I would never allow himself a visit that he paid to England in June 1844 to discuss with the British top officials in a confidential setting the form and prospects for partnership in the "Eastern Question". The talks went quite smoothly and encouragingly. The parties stated their mutual interest in maintaining the status quo in the Ottoman Empire. Under the conditions of extremely tense relations with France and the United States, London was glad to receive the most authentic assurances from Nicholas I personally about his continued readiness to respect the vital interests of Great Britain in the most sensitive geographic points for her.

However, for R. Peel and D. Eberdin, there was nothing shocking about the king’s proposal to conclude a general Russian-English agreement (something like a protocol of intent) in case spontaneous disintegration of Turkey urgently requires coordinated efforts from Russia and England to fill the vacuum formed on the basis of the equilibrium principle. According to Western historians, the 1844 talks of the year brought a spirit of mutual trust in Russian-English relations. In one study, the king’s visit was even called the “apogee of detente” between the two powers.

This atmosphere was maintained in subsequent years and ultimately served as a kind of insurance during the crisis that arose between St. Petersburg and London in connection with the demand of Nicholas I to the Port for the extradition of Polish and Hungarian revolutionaries (autumn 1849 of the year). Fearing that the Sultan’s refusal would force Russia to use force, England resorted to a warning gesture and led its military squadron into Bezik Bay. The situation escalated when, in defiance of the spirit of the London Convention 1841, the British ambassador in Constantinople, Stretford Canning, ordered the British warships to be stationed directly at the entrance to the Dardanelles. Nicholas I judged that it was not worthwhile to follow the path of the escalation of the conflict because of the problem concerning not so much Russia as Austria, which was eager to punish the participants of the Hungarian uprising. In response to the personal request of the Sultan, the king refused his demands, and Palmerston disavowed his ambassador and apologized to St. Petersburg, thereby confirming England’s loyalty to the principle of closing the straits for military courts in peacetime. The incident was settled. Thus, the idea of a Russian-English compromise partnership as a whole stood the test to which it underwent largely due to the attendant circumstances that did not have a direct relationship to the true content of the differences between the two empires.

These ideas, expressed mainly in Western historiography, do not mean that Nicholas I was infallible in analyzing potential threats and actions dictated by the results of this analysis. The London office made quite symmetrical mistakes. Most likely, these inevitable costs on both sides were not due to the lack of willingness to negotiate and the lack of sound logical messages. If something really was not enough for a sustainable strategic partnership between Russia and England, then this would be a comprehensive awareness of each other’s plans, absolutely necessary both for complete trust, and for full compliance with the rules of rivalry, and for correct interpretation of situations when it seemed like a position London and St. Petersburg are the same. It is the problem of the most correct interpretation that has become at the forefront of Russian-English relations in the 1840-e - the beginning of the 1850-s.

Of course, a strict account here must be presented first of all to the emperor himself, his ability and desire to delve deeply into the essence of things. However, it should be said that the British were not too zealous in arranging all the points above the “i”, making the situation even more confusing and unpredictable when it required simplification and clarification. However, the complexity of the procedure for an exhaustive clarification between Petersburg and London of the essence of their positions in the "Eastern Question" to some extent justified both sides. Thus, with all the external success of the 1844 negotiations of the year and due to different interpretations of their final meaning, they carried a certain destructive potential.

The same can be said about the fleeting English-Russian conflict 1849 of the year. Being surprisingly quick and easy, he ended up being a dangerous foreboding precisely because Nicholas I and Palmerston made different conclusions then from what had happened (or, more precisely, from the one that had not happened). The king took the apologies made by the British Secretary of State for Stratford-Canning's arbitrariness, as well as the Foreign Office’s statement about the steady adherence to the London 1841 Convention as a new confirmation of England’s unchanged course towards business cooperation with Russia on the “Eastern issue”. Based on this assessment, Nicholas I readily gave London a counter signal in the form of rejection of claims to Porte, which, according to his expectations, should have been regarded as a broad gesture of goodwill towards both England and Turkey. Meanwhile, Palmerston, who did not believe in such gestures, decided that the tsar simply had to retreat before pressure and, therefore, thereby recognize the effectiveness of applying such methods to him.

As for the international diplomatic consequences of the 1848 revolutions of the year, they consisted not so much that there was a real threat to the pan-European world and the Vienna order, but to the appearance of a new potentially destructive factor, to which Nicholas I certainly was not involved: at the helm all the great powers except Russia, the guardians were replaced by revisionists. By virtue of their political worldview, they objectively opposed the Russian emperor, now the only defender of the post-Napoleonic system.

When a dispute arose about the “holy places” (1852), he was not given meaning neither in England, nor in Russia, nor in Europe. It seemed to be an insignificant event also because it had no direct relation to Russian-English relations and was still not very dangerously affecting Russian-Turkish relations. If a conflict was brewing, it was primarily between Russia and France. For a number of reasons, Napoleon III was drawn into the litigation, Nicholas I and Abdul-Mejid were dragged in there, and later - the London office.

Abdul-Majid I

Abdul-Majid IFor the time being, nothing foreshadowed any particular trouble. The European "concert" in some cases, Russia and England - in others it was not just that they had to face and resolve much more complex conflicts. The feeling of confidence did not leave Nicholas I, who believed that he could not be afraid of French wiles or Turkish obstruction, having in his political assets more than a decade of experience in partnership with England. If this was a delusion, until the spring of 1853, London did nothing to dispel it. The head of the coalition government, Eberdin, who had a special favor with Nicholas I, voluntarily or involuntarily lulled the Russian emperor. In particular, the prime minister removed Palmerston from the Foreign Office, who spoke for the hard line. No wonder that the king regarded this personnel movement as a hint of the continuing "cordial harmony" between Russia and England. It would be better if Eberdin left Palmerston at the helm of foreign policy, so that Nicholas I could get rid of illusions in time.

Much has been written in historical literature about the role of another “fatal” factor contributing to the emergence of the Crimean War. The confidence of Nicholas I in the presence of deep, fraught with war contradictions between England and France is regarded as another "illusion" of the king. Meanwhile, the facts do not give any opportunity to agree with such an assessment. Starting from a very dangerous crisis around Tahiti (summer 1844 of the year), Anglo-French relations, up to 1853, were in a permanently tense state, sometimes in close proximity to the brink of collapse. The British kept their navy in the Mediterranean Sea and other areas in full combat readiness against the French. The British leadership was absolutely seriously preparing for the worst and, most importantly, for the real, from his point of view, scenario — the landing of the 40-thousand French army on the British Isles in order to capture London.

The growing sense of vulnerability has forced the British to demand from their government that they increase the land army, regardless of costs. The coming to power of Louis Napoleon horrified people in Britain who remembered the misfortunes and fears brought by his famous uncle, who associated it name with absolute evil. In 1850, there was a break in diplomatic relations between London and Paris due to Britain’s attempt to use force against Greece, where a wave of anti-British sentiment arose, caused in a generally insignificant episode.

The military alarm of the winter months of 1851 - 1852 in connection with the coup in Paris and its repetition in February-March of 1853 showed once again: Britain had reasons to consider France as the number one enemy. The irony is that only a year later she was already fighting not against the country that caused her so much concern, but against Russia, with which London, in principle, did not object to enter into an alliance against France.

No wonder that after the famous conversations with the British envoy in St. Petersburg G. Seymour (January-February 1853) on the "Eastern Question", Nicholas I continued to be dominated by ideas that until the beginning of the Crimean War few of the Western and Russian observers of of time would venture to call "illusions." In historiography, there are two views (apart from the shades between them) on this very complex plot. Some researchers believe that the king, having raised the topic of dividing Turkey and having received a supposedly unambiguously negative response from Britain, stubbornly did not want to notice what is impossible to overlook. Others with varying degrees of categorical admit that, firstly, Nicholas I only probed the ground and, as before, raised the question of probabilistic development of events without insisting on their artificial acceleration; secondly, the ambiguity of the reaction of London actually provoked the king's further mistakes, because it was interpreted by him in his favor.

In principle, there are plenty of arguments to justify both points of view. "Correctness" will depend on the placement of accents. To confirm the first version, the words of Nicholas I will do: Turkey “may suddenly die with us (Russia and England. - V. D.) in his arms”; perhaps the prospect of “distributing the Ottoman legacy after the fall of the empire” is not far off, and he, Nicholas I, is ready to “destroy” Turkey’s independence, reduce it “to the level of a vassal and make existence itself a burden for it”. In defense of the same version, one can cite the general provisions of the response message of the British side: Turkey does not threaten disintegration in the near future, therefore it is hardly advisable to enter into preliminary agreements on the division of its inheritance, which among other things will arouse suspicion of France and Austria; even the temporary occupation of Constantinople by the Russians is unacceptable.

However, there are many semantic accents and nuances confirming the second point of view. Nicholas I bluntly stated: “It would be unreasonable to desire more territory or power” than he possessed, and “present-day Turkey is a neighbor that you cannot imagine better,” so he, Nicholas I, “does not want to take the risk of war” and “ will never take over Turkey. ” The emperor emphasized: he asks London for "no obligation" and "no agreement"; "This is a free exchange of views." In strict accordance with the instructions of the emperor, Nesselrode inspires the London office that "the fall of the Ottoman Empire ... we do not want either (Russia. - V.D.) nor England, and the disintegration of Turkey with the subsequent distribution of its territories is a" purest hypothesis " , although, of course, worthy of "consideration".

As for the text of the answer of the Foreign Office, there was enough sense uncertainty in it to disorient not only Nicholas I. Some phrases sounded quite encouraging for the king. In particular, he was assured that the British government did not doubt the moral and legal right of Nicholas I to stand up for the Christian subjects of the Sultan, and in the case of "the fall of Turkey" (this phrase was used), London would not do anything "without prior advice from the Emperor of Russia ". The impression of complete mutual understanding was supported by other facts, including the statement of G. Seymour (February 1853 of the year) about his deep satisfaction with the official notification to the Foreign Office, transmitted by the Nesselrod, that there was no case between St. Petersburg and Porto those that can exist between two friendly governments. " The Foreign Office instruction to Seymour (from 9 February 1853 of the year) began with such a notice: Queen Victoria “is happy to note the moderation, sincerity and friendly disposition” of Nicholas I to England.

Queen Victoria English

From London, there was no noticeable attempt to dispel the impression that he objected, not about the essence of the king’s proposal, but about the way and time of its implementation. In the argument of the British, the leitmotif sounded a call not to be ahead of events, so as not to provoke their development in a detrimental scenario for Turkey and, possibly, for universal peace in Europe. Although Seymour noted in his conversation with the king that even very sick states "did not die so quickly," he never allowed himself to categorically deny such a prospect for the Ottoman Empire and, in principle, allowed for the possibility of an "unforeseen crisis."

Nicholas I believed that this crisis, more precisely, its lethal phase, will occur earlier than it is thought in London, where, by the way, Ports also evaluated the viability of the ports in different ways. The king was afraid of the death of the "sick man" no less than the British, but unlike them, he wanted certainty for the same "unforeseen" case. Nicholas I was annoyed that the British leaders did not notice or pretend that they did not understand his simple and honest position. Still adhering to a cautious approach, he proposed not a plan for the collapse of Turkey and not a specific deal about the division of her inheritance. The king called only to be ready for any turn of the situation in the Eastern crisis, which was no longer a hypothetical perspective, but a harsh reality. Perhaps the surest key to understanding the essence of the emperor's fears is given by his words to Seymour. Nicholas I, with his characteristic frankness and sincerity, said: he is not worried about the question “what to do” in the case of the death of Porta, but about what should not be done. ” London, unfortunately, chose not to notice this important confession or simply did not believe it.

However, at first the consequences of the misinterpretation of the British answer by Nicholas I did not seem catastrophic. After explanations with London, the sovereign acted no less carefully than before them. He was far from going ahead. The reserve of prudence from the statesmen of Britain and other great powers, who feared the Eastern crisis would grow into a European war with completely unpredictable prospects, also seemed very solid.

Nothing irretrievably fatal happened neither in spring, nor in summer, nor even in autumn of 1853 (when hostilities began between Russia and Turkey). Until that moment when nothing could be done, there was a lot of time and opportunity to prevent a big war. In varying degrees, they persisted until the beginning of the 1854 year. Until the situation finally “entered into a corkscrew”, she repeatedly gave hope to scenarios that allowed Eastern crises and military alarms in 1830 - 1840 to be resolved.

The king was convinced that in the event that a situation of irreversible decay arises as a result of internal natural causes, it would be better for Russia and Britain to have an agreement in advance on a balanced division of the Turkish inheritance than to feverishly solve this problem under extreme conditions of the next Eastern crisis with unobvious chances success and a very real opportunity to provoke a pan-European war.

In the context of this philosophy, Nicholas I can be assumed: he did not renew the Unkjar-Iskelesi Treaty primarily because he expected in future to exchange London’s consent to the division of the property of the “sick person” if his death would be inevitable. As is known, the emperor was deceived in his expectations.

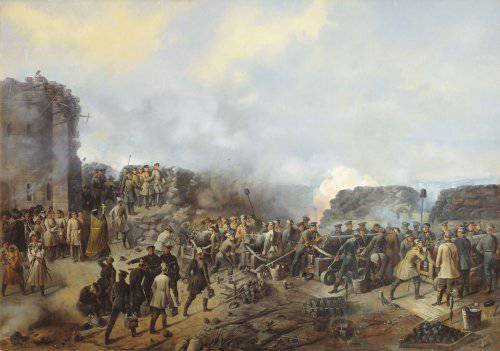

The Russian-Turkish war in Transcaucasia began on October 16 (28) on 1853, with a sudden night attack on the Russian border post of St. Nicholas of the Turkish parts of the Batumi Corps, which, according to the French historian L. Guerin, “conspired from marauders and robbers,” who in the future still had to “gain sad glory”. They almost completely cut out the small garrison of the fortress, not sparing women and children. “This inhuman act,” wrote Guerin, “was only a prelude to a series of actions not only against Russian troops, but also against local residents. He had to revive the old hatred that had long existed between the two nations (Georgians and Turks. - V. D.) ”.

In connection with the outbreak of the Russian-Turkish war, A. Czartoryski and KHNUMX again returned to their favorite plans to create a Polish legion in the Caucasus, where, according to the prince, “they can mature ... situations dangerous for Moscow”. However, hopes for the rapid military successes of Turkey soon dissipated. After the defeat at Bashkadyklyar 0 on November 27, the Turkish Anatolian army, which came in a rather deplorable state, became the subject of growing concern to Britain and France.

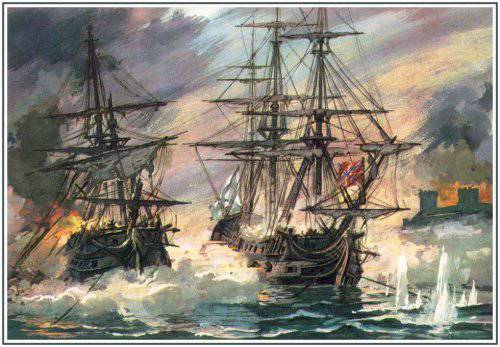

But a truly staggering impression in European capitals, especially in London, produced a Sinop defeat, which served as a pretext for the decision of the Western powers to enter the Anglo-French squadron into the Black Sea. As you know, the expedition of P. S. Nakhimov to Sinop was dictated by the situation in the Caucasus, from the point of view of military logic and the interests of Russia in this region seemed perfectly justified and timely.

Since the beginning of the Russian-Turkish war, the Ottoman fleet regularly traveled between the coast of Asia Minor and Circassia, delivering to the highlanders weapon and ammunition. According to information received by the Petersburg cabinet, the most impressive of such operations involving large airborne forces, on the advice of the British ambassador to Constantinople, Stratford-Canning, were intended to be carried out in November 1853. Delay in countermeasures threatened to complicate the situation in the Caucasus. The Sinop victory prevented the development of events that was detrimental to Russian influence in that region, which acquired special significance on the eve of the entry of Britain and France into the war.

In the rumble of artillery at Sinop, the London and Paris offices preferred to hear a “loud slap” in their address: the Russians dared to destroy the Turkish fleet, one might say, in front of European diplomats who were in Constantinople with a “peacekeeping” mission, and the Anglo-French military squadron, arrived in the Straits in the role of Turkey’s security guarantor. The rest did not matter. In Britain and France, newspapers reacted hysterically to what happened. Calling the Sinop case "violence" and "shame", they demanded revenge.

In the British press, the old, but in this situation, completely exotic argument was reanimated that Sinop is a step on the path of Russian expansion into India. No one bothered to think about the absurdity of this version. Single sober voices, trying to curb this revelry of fantasy, drowned in the choir of the masses, almost maddened by hatred, fears and prejudices. The question of entering the English-French fleet to the Black Sea was a foregone conclusion. Upon learning of the defeat of the Turks at Sinop, Stratford-Canning joyfully exclaimed: “Thank God! This is a war. ” Western offices and the press deliberately hid from the general public the motives of the Russian maritime action, in order to pass it off as an “act of vandalism” and blatant aggression, to cause “just” public indignation and free yourself.

Given the circumstances of the Battle of Sinop, it is difficult to call him a good excuse for the attack of Britain and France on Russia. If the Western offices were really worried about the peaceful resolution of the crisis and the fate of Porta, as they had said, then such an institution of international law as mediation, which they used only formally - to divert their eyes, was at their service. The "guardians" of the Turks could easily have prevented their aggression in the Transcaucasus and, as its consequence, the catastrophe at Sinop. The problem of defusing the situation was simplified already when Nicholas I realized that the Russian-Turkish conflict could not be isolated, and, having discerned the silhouette of the coalition against Russia, began in May 1853 a diplomatic retreat along the whole front, although to the detriment of his vanity. To achieve a peaceful détente from Britain and France, it was not even necessary to counter efforts, but very little: not to prevent the Tsar from going to understand. However, they tried to close him this way.

Both before and after Sinop, the question of war or peace depended more on London and Paris than on St. Petersburg. And they made their choice, preferring to see in the victory of the Russian weapon what they had so long and ingeniously searched for - the opportunity to throw a cry about saving "defenseless" Turkey from "insatiable" Russia. The Sinop events, presented to European society at a certain angle through well-established information filters, played a prominent role in the ideological preparation for the entry of Western countries into the war.

The idea of "curbing" Russia, in which Britain and France clothed their far from disinterested thoughts, fell on the fertile soil of the anti-Russian sentiments of the European, especially British, man in the street. For decades, the image of “greedy” and “assertive” Russia has been cultivated in his mind; mistrust and fear of it were brought up. At the end of 1853, these Russophobic stereotypes came in handy for the governments of the West: they could only pretend that they were forced, in obedience to an angry crowd, to save their faces.

In the well-known metaphor “Europe drifted to war,” containing a hint of factors independent of the will of the people, there is some truth. Sometimes it did seem that the efforts to achieve a peaceful outcome were inversely proportional to the chances of preventing a war. Still, this “inexorable drift” was helped by the living characters of the story, a lot of which depended on the views, actions and characters. The same Palmerston was obsessed with hatred of Russia, which often turned him from a deeply pragmatic politician into a simple English man in the street, upon whom the journalist-like bullshit of journalists acted like a red rag against a bull. In his post as Minister of the Interior in the Eberdin government from February 1852 and February 1855, he did everything to prevent Nicholas I from saving his face, and so that the Eastern crisis of the beginning of the 1850 began to develop into the Russian-Turkish war, and then Crimean.

Immediately after entering the Allied fleet into the Black Sea, the Anglo-French squadron of six steamboats, together with six Turkish ships, delivered reinforcements, weapons, ammunition and food to Trabzon, Batum and the post of St. Nicholas. The establishment of the blockade of the Russian ports of the Black Sea was presented to St. Petersburg as a defensive action.

Nicholas I, who did not understand such logic, had every reason to conclude that an open challenge was thrown to him, which he simply could not help but answer. Perhaps the most surprising thing is that even in this situation, the Russian emperor is making the last attempt to keep peace with Britain and France, more like a gesture of despair. Overcoming a sense of indignation, Nicholas I notified London and Paris of his readiness to refrain from interpreting their action as the actual entry into the war on the side of Turkey. He proposed to the British and French officially announce that their actions are aimed at neutralizing the Black Sea (that is, the non-proliferation of war in its waters and coast) and therefore equally serve as a warning to both Russia and Turkey. It was an unprecedented humiliation for the ruler of the Russian empire in general and such a person as Nicholas I, in particular. One can only guess what this step cost him. The negative response of Britain and France was tantamount to a slap on the arm outstretched for reconciliation. The king was denied very little - the ability to save face.

Already someone who, and the British, sometimes pathologically sensitive to the issues of protecting the honor and dignity of their own state, should have understood what they did. What kind of reaction could Nicholas I expect from the British diplomatic system, not the most senior representatives of which, accredited in the countries of the Near and Middle East, had official authority to summon their navy to punish those who dare to insult the English flag? Some British consul in Beirut could afford to resort to this right because of the slightest incident in which he wanted to see the fact of the humiliation of his country.

Nicholas I acted as any monarch who had any self-respecting himself had to do in his place. Russian ambassadors were recalled from London and Paris, British and French - from St. Petersburg. In March 1854, the maritime powers declared war on Russia, after which they received the legal right to help the Turks and deploy full-scale military operations, including in the Caucasus.

The answer to the question whether there was an alternative to the Crimean War and which one does not exist. He will never appear, no matter how much we succeed in the "correct" modeling of certain retrospective situations. This, however, does not in any way mean that the historian does not have the professional right to study the failed scenarios of the past.

It has. And not only the right, but also the moral obligation to share with the modern society in which he lives physically, his knowledge about the disappeared societies in which he lives in his mind. This knowledge, regardless of how demanded it is by the current generation of world destiners, must always be available. At least in the case when and if the powers that be are ripe to understand the usefulness of the lessons of history and ignorance in this area.

No one except the historian is able to visually explain that peoples, states, humanity periodically face large and small forks to the future. And for various reasons, they do not always make a good choice.

The Crimean War is one of the classic examples of just such an unsuccessful choice. The didactic value of this historical plot is not only in the fact that it occurred, but also in the fact that, under a different set of subjective and objective circumstances, it could probably have been avoided.

But the most important thing in the other. If today, in the event of regional crises or pseudo-crises, the leading global players do not want to hear and understand each other, clearly and honestly agree on compromise boundaries of their intentions, adequately assess the meaning of words and believe in their sincerity, without thinking the chimeras, control in the same “strange” and fatal way as in 1853. With one significant difference: there will most likely be no one to regret the consequences and correct them.

Information