"White Rajah": as a British dynasty, a hundred years rule on the island of Kalimantan

Kalimantan for a long time was a kind of periphery of the Indonesian civilization, because it did not have a developed economy and was inhabited by warlike Dayak tribes that were at a lower stage of development than the Malays, Javanese and some other peoples of the archipelago.

Kalimantan for a long time was a kind of periphery of the Indonesian civilization, because it did not have a developed economy and was inhabited by warlike Dayak tribes that were at a lower stage of development than the Malays, Javanese and some other peoples of the archipelago. However, statehood in Kalimantan appeared relatively early. Already at the beginning of our era, the Malays began to actively populate the island, which laid the foundations of the local state tradition. However, the inner regions of Kalimantan remained virtually undeveloped, since the resources of the Malay principalities were not enough to send aggressive expeditions to the island’s jungle and subdue the Dayak tribes living there. Dayaks, which means “pagans” in Malay, are Austronesian peoples and tribes that once migrated from the north, from mainland Asia, to the territory of Kalimantan Island and turned into local Aborigines. For a long time, the Dayaks kept the traditional culture practically in an unshakable state, adhering to traditional beliefs and not wanting to accept other religions. Dayaks did not know the traditions of statehood, and therefore Malays were among the beginnings of the first state formations in Kalimantan - people with more developed state and cultural traditions, who in the Middle Ages played a key role in navigation and trade in the Indian Ocean. Initially, the Malayan states in Kalimantan, like the whole archipelago, professed Hinduism with a strong influence of Buddhism.

Brunei Sultanate

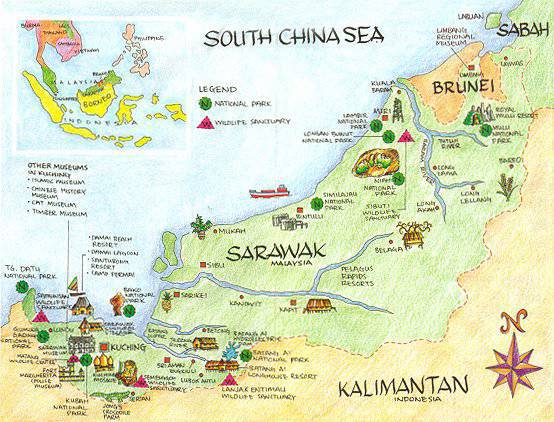

Brunei SultanateHowever, in the XIV-XV centuries. The processes of Islamization of Kalimantan began to grow, culminating in the adoption of Islam as the official religion of the state of Brunei, located in the northern part of the island. Islamization contributed to the strengthening of trade, economic and political relations of Brunei with Malacca. Strengthening the economic power of the country allowed the Sultans of Brunei to establish their authority throughout the territory of North Kalimantan. In the province of Sarawak, which is located in the north-west of the island, the authority of the relatives of the Sultan dynasty, who occupied the hereditary post of the Rajas of Sarawak, was established. They enjoyed considerable autonomy in the provinces' internal affairs and in fact represented semi-independent rulers, since the Sultan of Brunei was very limited in his choice of means of pressure on his vassals.

In the 16th century, in Southeast Asia, a new powerful military-political and economic force emerged, with the presence of which the indonesian, Malay and Filipino sultans and rajis, who were considered unshakable, could not but be considered yesterday. They were European colonizers - first the Portuguese and then the Spaniards, the Dutch and the British. The Europeans sought to take control of the most important trade routes through which the export of spices and other valuable goods of local origin were carried out from the islands of the Malay Archipelago. The island of Kalimantan was not overlooked by Europeans. Back in 1526, the Portuguese traveler Jorge de Menezes was in Brunei who managed to negotiate with the Sultan of Brunei about the supply of pepper and other best-selling goods to the Portuguese trading post in Malacca. By the name of the Sultanate of Brunei, the Portuguese, and then other Europeans, began to call the whole island of Kalimantan - Borneo.

Collaborating with the Portuguese, Brunei was in a hostile relationship with Spain. The latter had its strategic interests here, as it was able to subjugate the neighboring Philippines and fought against the Muslim sultans of the Southern Philippines who did not want to reconcile themselves to the Madrid authorities. Brunei supported the co-religionists for some time. Therefore, there is nothing surprising in the fact that since 1565 sea clashes have been observed between the Spanish and Brunei fleets. In 1571, Spain conquered Mainila and Tondo, cities in the Philippines that were closely associated with Brunei. The Sultan of Brunei set about forming a fleet to free Manila, but the operation never began. But the Spaniards managed to overcome the resistance of the Sultanate of Sulu, and then attack Brunei himself. But Madrid did not have the strength to conquer the Kalimantan Sultanate and the Spanish fleet had to retreat. In 1580, an attempt by the Spaniards to land in the north of Kalimantan was thwarted by Brunei troops.

Starting from the XVII century. there is a gradual economic decline of Brunei. The creation of trading posts by the Portuguese and the Dutch in the Malay Archipelago contributed to a decrease in the turnover of the Brunei port. On the other hand, trying to find other sources of replenishing their incomes, the Brunei sultans allowed pirate flotillas operating in the nearby seas and straits to be based on the territory of the sultanate. This did somewhat improve the material situation of the Brunei aristocracy, but it also contributed to the deterioration of relations between Brunei and the rest of the world. Moreover, the emergence in the domestic policy of the Sultanate of such a factor as the presence of armed groups of pirates did not contribute to the political stability of the state. The fragmentation of the country into separate feudal possessions increased, the central government significantly weakened its influence, especially in the peripheral provinces of North Kalimantan.

The next event that seriously changed the course of historical development in the region was the appearance of the British. In Singapore, a British colony and trading post was created, after which the British authorities began to show an increased interest in ensuring the safety of trade and navigation in the waters of the Malay Archipelago. First of all, the British naval command decided to defeat the pirates who were operating in the South China Sea, for which it was necessary to exert a corresponding influence on the sultanate of Brunei. By the beginning of the XIX century, the power of the Sultan of Brunei over the regions of North Kalimantan was finally weakened. The governors appointed by the Sultan actually became independent rulers, relying on pirate flotillas and their own military units. Their behavior caused discontent of the Dayaks who inhabited most of the island’s territory.

Militant Dayak - “bounty hunters” who preserved this ancient and terrible custom, brought many problems to the Brunei sultan, because he most often failed to cope with their uprisings. When in 1830's Dayak uprising broke out in the northwestern province of the Sarawak Sultanate, the sultan sent an army led by Crown Hashim to suppress it. It turned out that the uprising was provoked by the policy of the local ruler Makot, who, with his indefatigable financial appetites and cruelty, set himself against the Sarawak Dayaks. Prince Hashim failed to suppress the uprising. Virtually the entire Sarawak was in the hands of the Dayak tribes and the Malay Prince retained power only over the capital of the province of Kuching and its surroundings.

The first "white rajah" and the creation of the kingdom

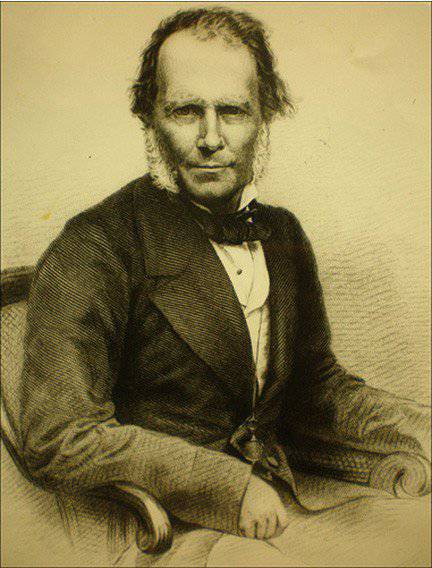

In 1838 in Brunei, someone named James Brooke appeared. This Englishman was a typical adventurer of the time, who sought to get rich in the southern colonies and, perhaps, make a career there that was inaccessible to him in the metropolis. Indeed, arriving on his own yacht, which he equipped after receiving the inheritance, James Brooke established contacts with Prince Hashim and was able to enlist his support. Brooke gave Hashim great help in suppressing the Dayak revolt of Saravak and gained the confidence of the Sultan's court. James Brooke himself was descended from an English family living in British India. He was born 29 on April 1803, in Indian Benares (now Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India). When he was young, he returned to England with his parents, in 1819, at the age of sixteen he joined the East India Company as a cadet and was promoted to lieutenant in 1821. The young officer participated in the Anglo-Burmese war, but in 1825 he was wounded and left for England. After a course of treatment and rehabilitating himself after being wounded, Brooke returned to India in 1830 in order to reinstate in military service, but he did not succeed. The twenty-seven-year-old retired officer was idle, but did not want to be bored for a long time. When Brooke's father died in 1835, who bequeathed a large sum of money to him, James equipped the ship, hired a crew, and went to Kalimantan Island (Borneo). Once in 1838 in Sarawak, Brooke took part in suppressing the Dayak uprising. For this, an Englishman who gained the confidence of the Brunei Sultan, 18 August 1841 was appointed governor of Sarawak and received the title of rajah. For the first time in history, a European has become a Malay raja.

In 1838 in Brunei, someone named James Brooke appeared. This Englishman was a typical adventurer of the time, who sought to get rich in the southern colonies and, perhaps, make a career there that was inaccessible to him in the metropolis. Indeed, arriving on his own yacht, which he equipped after receiving the inheritance, James Brooke established contacts with Prince Hashim and was able to enlist his support. Brooke gave Hashim great help in suppressing the Dayak revolt of Saravak and gained the confidence of the Sultan's court. James Brooke himself was descended from an English family living in British India. He was born 29 on April 1803, in Indian Benares (now Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India). When he was young, he returned to England with his parents, in 1819, at the age of sixteen he joined the East India Company as a cadet and was promoted to lieutenant in 1821. The young officer participated in the Anglo-Burmese war, but in 1825 he was wounded and left for England. After a course of treatment and rehabilitating himself after being wounded, Brooke returned to India in 1830 in order to reinstate in military service, but he did not succeed. The twenty-seven-year-old retired officer was idle, but did not want to be bored for a long time. When Brooke's father died in 1835, who bequeathed a large sum of money to him, James equipped the ship, hired a crew, and went to Kalimantan Island (Borneo). Once in 1838 in Sarawak, Brooke took part in suppressing the Dayak uprising. For this, an Englishman who gained the confidence of the Brunei Sultan, 18 August 1841 was appointed governor of Sarawak and received the title of rajah. For the first time in history, a European has become a Malay raja. Initially, James Brooke as a patriot of his native England was no longer interested in the prospect of becoming an Eastern despotic ruler, but in transferring a province in which, by fate, he was in power, under the protectorate of the British crown. However, London did not take with enthusiasm the idea of James Brooke. The fact is that in the period under review in England, the concept of abandoning new territories was widespread among the political elite, because the treasury did not want to bear the costs of maintaining the administrative structures and ensuring the defense of new colonies. Moreover, Saravak was not a promising region in economic or military-strategic terms — it was a pure periphery of Southeast Asia and the Malay Archipelago itself.

The establishment of a British protectorate over Sarawak James Brooke was denied, but England did not leave its citizen, who became a Kalimantan rajah, without military assistance. The British flotilla provided Brooke with irreplaceable support in the fight against pirates operating in coastal waters, as well as dayakas who rose from time to time. When a squadron of British naval forces arrived in 1845 on the shores of North Kalimantan, James Brooke was able to regain influence at the court of his friend Prince Hashim and his brother Hashim Prince Bedreddin. However, in the spring of 1846, as a result of the mutiny, Hashim and Bedreddin were killed. The power in the sultanate was seized by a group of Malay aristocrats who had a negative attitude towards James Brooke and his anti-piracy activity. The conflict was between Brooke and his Malay rivals was inevitable, and it ended in favor of the “white rajah”. With the help of the British squadron, Admiral Concrana, Brooke took Brunei by storm, after which the Sultan Omar Ali, under the fear of shelling the city, was forced to sign an agreement to grant Sarawak sovereignty and rights to James Brooke to manage the former Brunei province as a sovereign monarch. At the same time, Brooke achieved the transfer of the island of Labuan under the control of Great Britain, which was going to use it as a naval base to fight pirates. For ten years, from 1847 to 1857. James Brooke, in parallel with the rule in Sarawak, served as the British governor of the island Labuan.

Fighting pirates, Chinese, and bounty hunters

At 1847, James Brooke was able to visit the UK, where he was greeted with great honors. Brooke was awarded the degree of Doctor of Law at the University of Oxford and was knighted. He, in addition to the governor's post in Labuan, also received the post of British Consul General in Brunei. Brooke was also responsible for organizing the fight against piracy in the South China Sea. In 1849, the ships of the British navy and the Sarawak flotilla attacked pirate ships stationed at Cape Batang-Mar. More than 90 pirated "prou" were sunk and about 400 people were killed. At the same time, the Dayaks who served in the Brook detachments cut off the heads of the 120 captive pirates. However, the defeat of the piracy flotilla entailed negative consequences. British parliamentarians, who already then began to show excessive tolerance to various villains, expressed dissatisfaction with the brutal, from their point of view, the actions of Brooke. A special parliamentary commission was even created to investigate the actions of James Brooke, which, however, justified him.

At the beginning of the 1850's to the pirates - the old enemies of Brooke - added another problem. By this time, quite a large Chinese diaspora had formed in Sarawak. The Chinese were here after quarreling with the Dutch authorities of West Kalimantan and were forced to emigrate to nearby Sarawak. Brooke initially accepted Chinese immigrants quite well, since he hoped for their positive role in the development of the Sarawak economy and saw in them a more “civilized” population than the Kalimantan Dayak and even Malays. But in exchange for the accommodation provided and the right to commercial activity or work, Brooke demanded complete control of the Chinese diaspora. Naturally, this was not to the liking of the leaders of the Chinese "secret societies" who controlled merchants, artisans and received income from the sale of opium.

At the beginning of the 1850's to the pirates - the old enemies of Brooke - added another problem. By this time, quite a large Chinese diaspora had formed in Sarawak. The Chinese were here after quarreling with the Dutch authorities of West Kalimantan and were forced to emigrate to nearby Sarawak. Brooke initially accepted Chinese immigrants quite well, since he hoped for their positive role in the development of the Sarawak economy and saw in them a more “civilized” population than the Kalimantan Dayak and even Malays. But in exchange for the accommodation provided and the right to commercial activity or work, Brooke demanded complete control of the Chinese diaspora. Naturally, this was not to the liking of the leaders of the Chinese "secret societies" who controlled merchants, artisans and received income from the sale of opium. In February, 1857, Chinese gold miners, formerly living and working in Central Sarawak, launched an offensive against the capital of the kingdom, Kuching. Bursting into the city, they killed several European families and staged mass robberies. Soon, however, a British steamer approached Kuching, whose artillery fire dispersed the Chinese. The resistance of the Chinese was suppressed by the armed forces of the Malay and Dayak soldiers under the command of Brooke. The remains of the surviving Chinese gold diggers fled to the Dutch part of Kalimantan. After these events, Brooke tightened his control over the Chinese population of Sarawak to an even greater degree, although he did not refuse to accept Chinese immigrants.

In 1863, the United Kingdom officially recognized Sarawak as an independent state under the administration of James Brooke. Thus, the “white rajah” received the actual legitimacy of the British authorities and could from that time consider itself one of the ruling monarchs of the world. 11 June 1868, at the age of 65 years, James Brooke passed away.

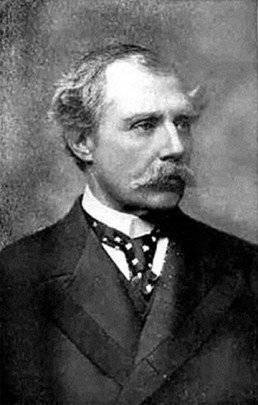

The throne of Raja Sarawak was succeeded by his nephew Charles Johnson Brooke (1829-1917). By this time he was 39 years old. The fact that he will take the Sarawak throne after the death of his uncle, Charles Brooke found out in 1861 year. True, in 1863, the uncle sent his nephew out of Sarawak, angry at his criticism of himself, but in 1865 he forgave and allowed him to return. The reign of Charles Johnson Brooke lasted almost half a century. The second "white rajah" continued the policy of his uncle to strengthen the Saravak statehood, and carried out this task at the expense of the territories of weakening Brunei, annexing more and more lands to his state. Ultimately, Brooke seized most of the land that once constituted the Brunei Sultanate, and Brunei turned into a dwarf state, within whose borders it remains up to the present.

The throne of Raja Sarawak was succeeded by his nephew Charles Johnson Brooke (1829-1917). By this time he was 39 years old. The fact that he will take the Sarawak throne after the death of his uncle, Charles Brooke found out in 1861 year. True, in 1863, the uncle sent his nephew out of Sarawak, angry at his criticism of himself, but in 1865 he forgave and allowed him to return. The reign of Charles Johnson Brooke lasted almost half a century. The second "white rajah" continued the policy of his uncle to strengthen the Saravak statehood, and carried out this task at the expense of the territories of weakening Brunei, annexing more and more lands to his state. Ultimately, Brooke seized most of the land that once constituted the Brunei Sultanate, and Brunei turned into a dwarf state, within whose borders it remains up to the present. When, in 1888, Great Britain established a protectorate over Sabah - the northern part of Kalimantan, located east of Sarawak, the lands under the control of the British crown in the north of the largest island of the Malay Archipelago actually closed up. The undoubted advantages of the rule of Charles Johnson Brooke, in addition to territorial seizures, can also be attributed to the fight against the Dayak tradition of “head hunting”. It was carried out as part of a general campaign to pacify the Dayaks who inhabited the hinterland of Sarawak and were rather cool about any government, including the rule of the “White Rajas” and the rule of the Brunei sultans. In 1893, a rebellion broke out under the leadership of Banting and Ngumbang. To suppress the uprising in the next year, 1894, Charles Brooke outfitted an armed detachment, but he failed. In 1902, another punitive detachment was sent, however, he was unable to complete the defeat of the rebels because of the outbreak of an epidemic of cholera. Only in 1908, the Dayak leader Banting, after fifteen years of war, recognized the power of the “white rajah”. However, in 1908-1909 and 1915. there were new Dayak uprisings.

The struggle with the bounty hunters was carried on by the sultans of Brunei. The latter, being Muslims, considered the pagan customs barbaric and dangerous for the state, but they could not eradicate the ancient tradition of the inhabitants of the Kalimantan jungle. Dayak could consider himself a man only after he brought the enemy's head into the tribe. Between individual tribes constantly went internecine wars that claimed many human lives. Charles Brooke officially banned the bounty hunt, after which he undertook a military operation against the Dayaks. Several tribal leaders were taken prisoner and defiantly executed, despite the fact that the ordinary Dayak soldiers were ordered to go home without any sanctions. Thus, Brooke was able to achieve support among ordinary Dayak and the tribes gradually began to move to peaceful forms of management.

World War II and Japanese occupation

After Charles Johnson Brooke passed away in 1917, his son Charles Weiner Brooke (1874-1963) was declared the new king of Sarawak. Like his father, Charles Weiner ascended the throne at an elderly age - he was already 43 of the year. The reign of Weiner Brook went down in history as the beginning of the Sarawak industrialization era. The kingdom began to develop the petroleum industry, the production of rubber. In domestic policy, Weiner Brooke continued his father’s policy - he adhered to the line of supporting local Dayak tribes, for which he prevented Christian missions in Sarawak, presenting himself as a defender of Dayak culture and traditions.

With the beginning of the Second World War, Japanese troops invaded Kalimantan in 1941. Charles Weiner Brook and his family managed to escape to Australia, to Sydney, where he was evacuated until the end of hostilities. Meanwhile, Japanese troops occupied the territory of Sarawak and maintained control of the kingdom until the end of the Second World War. However, the British switched to the tactics of guerrilla war against the Japanese invaders, appealing to the long-standing military traditions of the Dayaks. For this, the British military had to revive the terrible custom of “head hunting”. For the head of each Japanese soldier, a dayak hunter - a dayak received ten dollars.

With the beginning of the Second World War, Japanese troops invaded Kalimantan in 1941. Charles Weiner Brook and his family managed to escape to Australia, to Sydney, where he was evacuated until the end of hostilities. Meanwhile, Japanese troops occupied the territory of Sarawak and maintained control of the kingdom until the end of the Second World War. However, the British switched to the tactics of guerrilla war against the Japanese invaders, appealing to the long-standing military traditions of the Dayaks. For this, the British military had to revive the terrible custom of “head hunting”. For the head of each Japanese soldier, a dayak hunter - a dayak received ten dollars. After that, the Dayak opened the "hunting season" for Japanese patrols. Armed with “sumpitans” - blow guns with poisonous arrows, - the Dayaks tracked down the Japanese in the jungle and killed their soldiers. At the same time, Dayak villages in the daytime showed complete peace and loyalty to the Japanese, without giving away the true nature of their men's activities as night fell. After the Japanese military command set an unkind trend of missing soldiers going on patrol, it decided to reinforce the patrol teams. After this, the attacks stopped, but at one time the Dayaks tried to hunt Chinese colonists, hoping to deceive the British officers and pass the severed heads of peaceful farmers - the Chinese behind the heads of Japanese soldiers. Naturally, the British command had to immediately cancel the payment for the head and take steps to notify Dayak about the termination of the "hunt."

Under the rule of Britain and Malaysia

In 1945, Sarawak was liberated by British troops. 15 April 1946, Charles Weiner Brooke returned to Sarawak. He received a proposal from London to transfer power over the kingdom of the British administration and 1 July 1946, receiving a large sum of money, abdicated the throne and left Sarawak with his daughters. However, far from the entire population of Sarawak was quite a transfer of power to the British administration. First, the locals, the Malays and the Dayak, were opposed to the British, especially since anti-colonial sentiments were spread among them by this time.

Secondly, another figure appeared, extremely dissatisfied with the decision of Charles Weiner Brooke. It was his nephew Anthony Brooke. Raja Mada Sarawak Anthony Walter Dyrell Brook (1912-2011) was born on December 10 1911 in England, in the family of Captain Bertrand Willes Dyrell Brook, where he received an education. Raja Charles Weinher Brook, he was a nephew. In 1930's Anthony held various administrative positions in the Sarawak government, and on August 25, 1937 was approved as heir to the throne. In 1939-1940 he replaced the post of the Rajah, but 17 January 1940 was deprived of the right to inherit the throne because of marriage with a woman of non-aristocratic origin. Thus, in April, 1941, the new heir to the throne, was the brother of the current Rajah Charles Weiner Brooke Bertrand Brooke - father of Anthony. However, in 1944, Mr. Anthony was reinstated in the right of succession to the throne. It should be noted that during the Second World War, Anthony Brooke enlisted in the British army and served in the rank of private, and then sergeant. In 1944, he was promoted to lieutenant and continued to serve in the Intelligence Corps on the island of Ceylon. In 1944-1945 Anthony served as special commissioner Sarawak in the UK and head of the Sarawak government in exile.

When Charles Weiner Brooke abandoned the royal throne at 1946 and handed Saravak under the control of Great Britain, Anthony disagreed with this decision of his uncle. The prince was supported by the Negri Council - the Sarawak parliament. For five years, Anthony Brooke advocated the independence of Sarawak and the expulsion of British colonial officials. In 1948, the British Governor Sarawak Duncan Stewart was killed, after which Anthony Brooke’s activities came to the attention of British intelligence. However, in 1951, Mr. Anthony Brooke abandoned claims to revive Sarawak’s independence and his rights to the throne. This was explained by the fact that in neighboring Malaya, there was a war against communist partisans, and the Communists were operating in most other countries of Southeast Asia. Choosing between the two "evils" - the communist revolution of the type of Vietnam and the British administration, Anthony Brooke, as befits a prince and a British, chose the latter. He went to Sussex, then to Scotland, and in 1987 he moved to New Zealand. 2 March 2011 Mr. Anthony Brooke died in New Zealand at the age of 98.

As for the fate of Saravak, he was under British control for almost two decades. 16 September 1963 Sarawak was incorporated into the Federation of Malaysia. As for the last rajah Sarawak Charles Weiner Brooke, he passed away in London 9 on May 1963 of the year, before 4 came to a month before such an important change in the life of his former kingdom. In 1962-1966 the territory of Sarawak was actively claimed by Indonesia, intending to establish control over the whole of Kalimantan. Indonesian special services were behind the backs of the partisans - the communists who were operating in the jungles of Sarawak against British and Malayan troops.

However, to develop a civil war in Sarawak, at least to the extent of the Malay War, the Indonesians did not succeed. Nevertheless, the activities of the Indonesian special services and the presence of communist partisans in the region affected political stability in Sarawak. Civil strife began between the Dayak tribes, between Dayak and Malays, Chinese and indigenous people. Against the communist partisans were forced to send military units not only the authorities of Malaya, but also the United Kingdom and Australia. 30 March 1964 in the Kalimantan jungle, a group of Chinese students led by Yapn Joo Chung and Wen Min Zhuang formed the organization Saravak People's Partisans, which included about 800 people - mostly Chinese by nationality. The communist guerrilla military training was carried out by the Indonesian communists with the support of the Indonesian military command, and the management team also received training in China. In the eastern part of Sarawak 26 in October 1965, the People’s Army of North Kalimantan was created - also led by a Chinese named Bong Ki Chok. With the hands of the communists, the Indonesian special services wanted to destabilize the situation in Sarawak and to achieve the separation of the state from Malaysia and its annexation to Indonesia. However, after Sukarno’s regime fell in 1965 and the “rightist” General Suharto came to power, Indonesia refused to support the communists. However, the guerrillas continued to operate, and even 30 in March 1970 merged into the Communist Party of North Kalimantan, which had fought against the Malaysian authorities for twenty years - until November 1990.

Today Sarawak is a province of Malaysia. 28 of various peoples and ethnic groups resides on its territory. Most of them are representatives of Indonesian peoples. 30% of the population of Sarawak is ibans, one of the Dayak peoples. Besides them, Malays live here, constituting about 25% of the population, and Chinese, also constituting 25% of the population. The remaining number of inhabitants falls on representatives of bidayu, melanau and other indigenous ethnic groups of Kalimantan. Religiously, the population of Sarawak is also variegated. Here live Muslims (Malays and part of the Dayak), Buddhists and Taoists (Chinese), Christians (part of the Chinese and Dayak), followers of local traditional cults (Dayak). Dayaks - followers of traditional beliefs in Indonesia are officially considered Hindus.

Economically, Sarawak is a fairly prosperous state of Malaysia. First, oil production is developed here, which ensures a relatively high level of well-being of the local population. Secondly, the state also exports wood and furniture, including expensive. The tourism industry is also gradually developing.

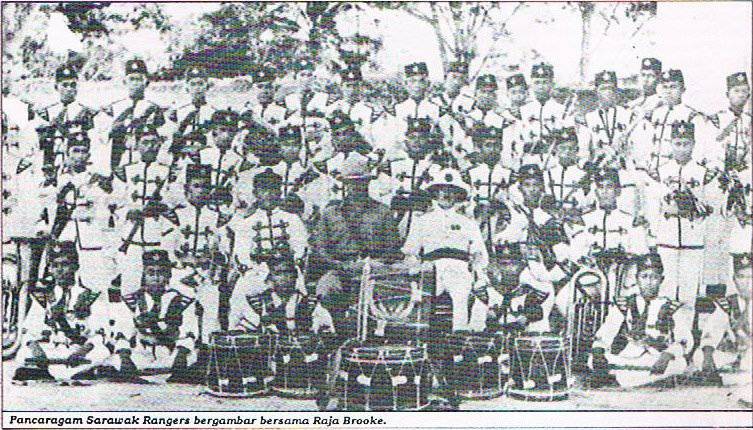

Sarawak Rangers

It is noteworthy that the traditions of the Sarawak armed forces continue in the Malaysian armed forces. Back in 1862, Mr. Johnson Brooke, then the heir to the throne, created an armed unit called the Sarawak Rangers. The history of this formation goes to 1846, when James Brooke created a squad defending Kuching from pirates. The first squad commander, William Henry Rodway, was a British officer who created the Sarawak Rangers in 1862, and then, from 1872 to 1891, re-commanded the unit. Sarawak Rangers were used both as an army and as a police unit — that is, its functions were similar to those of the National Guard, gendarmerie or internal troops. The rank and file rangers of the Rangers were originally recruited from among the representatives of the indigenous population - Malays and even Dayaks, and the officers were usually the British or other Europeans hired by the "white rajahs" for military service.

In service with the detachment weapon Western-style rifles and artillery guns, as well as the national Malay and Dayak weapons. Rangers carried guard duty in several fortresses built in strategically important places - near cities and in river mouths. The functions of the "Saravak Rangers" included: guarding the state border of Sarawak, fighting against rebels and pirates, protecting public order. In the 1930s, the Saravak Rangers division was disbanded, but in 1942, at the initiative of the British, it was decided to re-create it. After the transfer of Sarawak to British control, the Rangers were also reassigned to the colonial administration. In the 1963 year, after the formation of Malaysia, the Sarawak Rangers were incorporated into the Malaysian Royal Ranger Regiment.

Information