Paper pennies and rolls of rubles

Russian monetary system in 1914-1917

In the Great War, the Russian Empire, with all the poverty of the majority of the population, entered, however, a rich state with stable finances. The country's monetary system relied on the gold and silver ruble. However, this currency, which was considered the hardest in peacetime, first retreated under the onslaught of total war - in the first months after it began, Russia's finances were left without a gold coin, in 1915, they had to print paper pennies, and by the end of 1917, the country's finances collapsed completely . How this happened - in the material "Russian Planet".

Gold, Silver and Copper Empire

According to the results of 1913, the balance of free funds in the treasury of the Russian Empire reached 433 million rubles - for comparison, it is exactly 3 times more than the Ministry of Public Education spent on all educational institutions of the country, from parochial schools to universities. In addition, Russia's gold reserves amounted to a record stories countries magnitude - over 1300 tons of precious metal worth over 1,5 billion rubles. These gold "holdings" were then the largest in the world.

One ruble at face value then contained 0,774235 gr. gold, and accordingly 1 million rubles represented the 774 kilogram of this precious metal. For comparison, this amount of gold in the 2014 year was worth about 35 million dollars.

Due to the huge gold reserves and strictly limited emissions, the gold coverage of paper money up to 1914 of the year approached 100%. All this made it possible, without limitation, to freely exchange paper rubles for gold, as the inscription read proudly on the notes of the Russian Empire: “The State Bank exchanges credit cards for a gold coin without limiting the amount”.

In circulation were gold and silver rubles, paper rubles, silver and copper pennies.

Gold coins were minted from gold of the highest standard, gold coins with denominations of 15 rubles (“imperial”), 10 rubles, 7 rubles 50 kopecks (“semi-imperial”) and 5 rubles were in circulation. At the beginning of the 20th century, the minting of gold and any other metal coins of Russia was carried out only in the capital of the empire at the Petersburg Mint.

1 ruble coins, 50 and 25 kopecks were minted from high-grade silver, and from low-end coins were made in 20, 15, 10 and 5 kopecks. A small copper coin of 5, 3, 2, 1, half-penny and a quarter of a penny was used as an auxiliary and changeable means.

Since 1907, in the Russian Empire, new samples of paper notes with advanced protection against fakes are being produced (protection really turned out to be high, having reliably protected the paper ruble from fakes). There were “state credit cards” in circulation, that is, paper notes with 3, 5, 10, 25, 100 and 500 rubles face values.

On 1 in January 1914, all types of currency were in circulation (gold, silver and paper rubles, silver and copper kopecks) in the amount of 2 231 million rubles, including gold coins for 494 million, silver rubles for 123 million, silver kopecks for 103 million and copper kopecks in the amount of 18 million rubles. Paper notes for January 1 1914 were in circulation for 1 664 million rubles, and the gold reserves of the state bank of the Russian Empire were estimated at 1 695 million rubles (of which 1 528 million were within the country and 167 million, that is, less than 10%, Abroad). This provided a gold cover of 101,8% paper rubles.

The end of the golden ruble

Four days before the official declaration of war on Germany, 27 July 1914, the State Duma adopted the law “On some financial measures due to wartime circumstances”, which suspended the free exchange of paper rubles for gold, which had been in effect in the country since 1897.

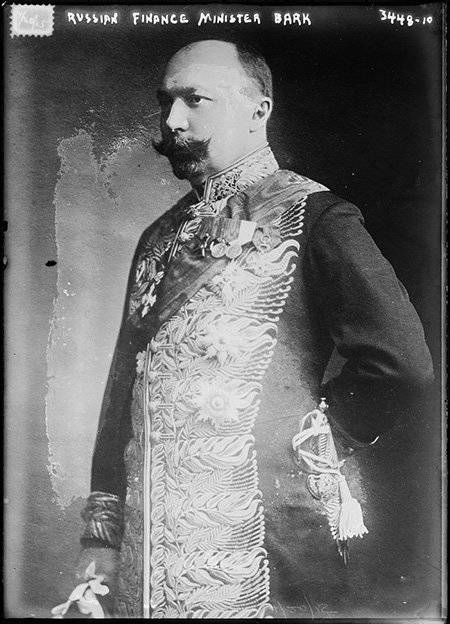

This was done at the insistence of the Ministry of Finance. The last Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire, Peter Lyudvigovich Bark was an experienced economist and on the eve of a big war he tried to save the gold reserves. At a meeting of the State Duma, he suggested immediately stopping the exchange of the paper ruble for gold “urgently, since every day of delay would lead to a reduction in gold reserves, the preservation of gold is the surest guarantee for the speedy restoration of metal circulation when wartime circumstances pass ...”

But it was already too late, for everyone the understandable threat of a big war in Europe had already matured for a month, and during that time, while officials and the media in all countries pumped military-patriotic hysteria, gold disappeared from circulation. The population, Russian and foreign merchants hid their gold and urgently changed a lot of paper bills to the precious metal. The law that suspended the exchange of paper for gold was catastrophically late - by August 1914, the treasury had only an insignificant part of gold rubles worth only 50 million, but 436 million gold rubles had settled in the population, hidden for a rainy day, and 452 million gold rubles went beyond the border.

The era of the golden ruble ended with the beginning of the First World War. Optimists, however, predicted that soon everything would be fine and even better than before the war. For example, almost all economists and financiers predicted that Russia will face a fall in prices that are strengthening the ruble, primarily for agricultural products. Its export with the opening of hostilities almost completely stopped, since the Baltic Sea was first blocked and in the fall, after Turkey entered the war, Black (the port of Murmansk and the railway to it were still only in the project).

But the benevolent predictions did not materialize. Low food prices were observed only in the first three months of the war, when, for example, eggs dropped in 2-3 times - to 4 – 9 kopecks for a dozen, butter - twice, to 7 – 8 rubles per pound; the price of barley (which then occupied the third place in the diet of the bulk of the population after rye and wheat) fell 4 times - to 22 – 23 kopecks per pound. Meat in the central provinces of Russia in the first months of the war fell by half, to 5 – 7 kopecks per pound.

In contrast to Western Europe, where a rise in prices was observed immediately, in Russia prices went up only from December 1914 of the year. This was due to the fact that the country's agriculture was still based on almost medieval technologies of manual labor, the main role was played by the working hands of men, but by the end of 1914, from the villages, more than 4 million peasants of working age had been called up. Therefore, by the spring of 1915, Russia began to catch up with England and Germany in food prices. By the first military spring, food prices in the Russian Empire had grown almost 1,5 times.

Financial problems were aggravated by the fact that with the start of the war the tsarist government, out of patriotic motives, refused the most important source of income - the state monopoly on the sale of vodka, introducing a “dry law”, which reduced the income of the treasury by almost a billion rubles annually.

His Majesty's printing press

The war from the first days caused a fantastic increase in spending. The number of armies in three years has grown 10 times - from 1 million 360 thousand in July 1914 to over 10 million "bayonets" on 1 in January 1917. Military spending grew from month to month: if before the war in 1913, Russia spent 826 million rubles on the army and navy, then in 1916, they spent 14,5 billion on them, and only in the first half of 1917, the expenses on army and navy reached 10 billion rubles.

In the autumn of 1914, the average daily military expenditures were 10-12 million rubles, in the first half of 1915, 19 million, and by the end of that year, 28 million daily. Over the 1916 year, military spending increased by almost one and a half times, reaching 46 million rubles a day, and by the February revolution 1917 reached the year 55 million rubles.

From the first days of the war, the issue of paper money was used to cover the state budget deficit. By the law of 27 in July 1914, the tsarist government granted the State Bank of the Russian Empire the right to put into circulation an additional over a billion paper rubles without gold. 17 March 1915 was released another billion paper rubles without any coverage. The following year, under the imperial decree from 29 of August, 1916 of the year printed unsecured gold “credit notes” worth up to 5,5 billion rubles, and in just 4 months at the suggestion of the Council of Ministers from December 27 of 1916, the number of unsecured paper rubles increased again by 6,5 billion.

If on 1 January 1914 of the year there were paper notes in the amount of 1633 million rubles, then on 1 January 1915 of the year - already 2 947 million, to 1916 year - 5 617 million, and on 1 January 1917 of the year - 9 103 million rubles. Thus, from July 1 1914 to March 1, 1917, the amount of paper money in Russia increased 6,7 times.

Formally, this should have devalued the ruble to about 15 pre-war kopecks. But in reality, the ruble exchange rate fell within the country only 4 times, to 25 kopecks, and in the foreign market - just to 56 kopecks.

Such a strange at first glance, the difference was caused by the huge, multi-billion dollar foreign loans that the belligerent Russia received from its allies in the Entente — Britain and France. That is, the tsarist government postponed the main stage of inevitable hyperinflation to “after victory”, when it would be time to repay the monstrously swollen external debts.

War and inflation have changed the content of the monetary system. If the hidden gold ruble disappeared from circulation already in the 1914 year, then a year later it was the turn of the silver ruble, which, following gold, the population and merchants began to hide “in pods” for a rainy day.

1914 year was the last year of mass minting of the silver ruble - then 536 thousand silver coins with the face value of 1 ruble were issued. Already in the 1915 year in the Russian Empire, the silver ruble was last minted, with a scanty circulation - just 5 thousand coins (according to other sources and even less - only 600 copies).

But the multi-billion dollar issue of paper money not only gave rise to inflation, but also demanded simplification of the technology of money production. To speed up the production of rubles, by decree of 6 December 1915 of the year began to produce the most popular paper notes in denominations of 1 ruble, not with a six-digit unique number each, but only with a series number, the so-called “military issue” of 1 million notes in one series.

Paper penny

War and inflation affected not only rubles, but pennies. Already in the summer of 1915, Russia began to feel an acute shortage of change coins, and the production capacity of the Petrograd Mint could not cope with huge orders for metal pennies. As a result, the tsarist government was forced to return to the minting of small coins abroad (earlier, in the 19th century, Russian loose change was minted in England more than once).

This time it was decided that silver 10 and 15-kopek coins would be minted in Japan from cheap silver purchased in China. So, for the 1915 year at the Osaka Mint, the Japanese produced 96 666 000 silver coins worth 15 kopecks for Russia. However, these emergency measures did not help, and by the beginning of 1916, the silver and copper coins, following the gold and silver ruble, also almost disappeared from circulation.

A complete series of copper coins was last minted in the 1916 year, because of the inflation they stopped minting penny and quarter-kopecks. Small silver coins of 20, 15 and 10 kopecks of low-grade metal were minted before the beginning of 1917, but they almost immediately settled in the pods of the population.

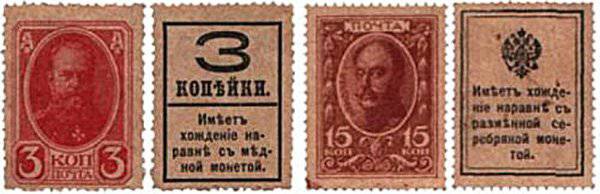

To eliminate the shortage of kopecks and to save expensive metals (copper from the beginning of the war just as much went up, as it was widely used in military production), the Council of Ministers decree of 25 September 1915 launched the issue of paper kopecks in the form of postage stamps of 1, 2, 3, 10, 15 and 20 kopecks, on the back of which were reported on their circulation along with a copper or silver coin. They could be used as postage stamps, and as a bargaining chip.

Decree from 5 December 1915 of the year went even further - paper pennies were officially put into circulation. It was already on the money- "postage stamps", and high-grade money, the so-called "treasury change banknotes" in denominations of 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 50 kopecks. However, denominations in denominations of 10, 15 and 20, although they were printed, they were not released and destroyed. But the paper penny 1, 3, 3, 4, 5 and 50 kopecks were widely accepted.

These "penny" bills were printed on thick paper and, of course, had far worse protection against fakes than paper rubles. If it was very difficult to make a fake ruble, then paper pennies soon began to be actively forged. Counterfeiters quickly flooded the domestic market with paper yellow-blue "coins" worth 50 kopecks. According to estimates of forensic experts, this fishery brought fabulous profits to counterfeiters - making a fake sheet on which one hundred paper “coins” with 50 kopeks were printed cost them only 10-15 kopecks.

The opponents of Russia did not remain aloof from the theme of “paper kopeks” - in Germany, they quickly produced a batch of fake kopecks, “postage stamps”, with 15 and 20 kopecks. An intentionally distorted version of the inscription in Russian was printed on them: “It has a course on par with the bankruptcy of a silver coin.” That is, such pennies “marks” became not only counterfeit money (the mass of the illiterate population could not distinguish a correct and distorted inscription), but also psychological weaponsaimed at undermining confidence in the monetary system of Russia.

However, first of all, this trust was undermined not so much by fake as inflation. The amount of paper money in circulation increased almost 6 times, and the real ratio of the gold reserves of the empire to the pulp was only 1% on 1917 January 16,2.

Ruble with a swastika

Two weeks after its creation, the Provisional Government resorted to emergency measures to improve the financial condition of the country. 30 March, 1917, the "Loan of Freedom" was announced. This loan was named because of the pompous treatment of the Provisional Government to the people of Russia: “A strong enemy deeply invaded our borders, threatens to break us and return the country to the old, now dead, system. Only the tension of all our forces can give us the desired victory ... Let’s lend money to the state by placing them in a new loan and save our freedom from destruction ”.

Loan bonds were issued in denominations of 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000, 10000, 25000 rubles. A bit later, bonds of a smaller nominal appeared, in 20 and 40 rubles. Bonds were issued for 49 years, at the rate of 5% per annum.

In spite of the massive propaganda released by the Provisional Government, the Loan on Freedom did not succeed, as recognized by the regular Minister of Finance of the Provisional Government Andrei Shingaryov: “Wealthy classes believed in the new order and came to its aid, while the masses of the population were mistrustful” . For 4 of the month, the number of subscribers to a loan among the population was only 674 thousand, and the Provisional Government received only 4 billion rubles, the amount by that time is completely insufficient.

Therefore, from the first days of work, the Provisional Government began a mass issue of paper money. Already 4 March 1917, a special decree of the State Bank was given the right to issue 8,5 billion unsecured rubles. This was followed by a number of decrees (15 in May, 11 in July, 7 in September, and 6 in October), which increased the issue volume to 16,5 billion rubles. In March, a little more than a billion rubles was printed, in April - about 0,5 billion, in May and June - in a billion, in August, 1,25 billion, in September and October they printed almost unsecured rubles in 2 billion.

By order of 9 in May 1917, the issue of 5 rubles denominations was started using a simplified technology - from now on, they, like the “military issue” of notes in 1 ruble, were printed not with an individual number, but only with a series number.

Along with the release of pre-revolutionary banknotes, the Provisional Government introduced its own rubles into circulation. By order of April 26, 1917 for the first time issued "state credit cards" with 250 and 1000 rubles. Their obverse sides contained a text that did not correspond to reality about exchange for a gold coin and a symbol unusual for Russian money - a cross with ends bent at right angles, that is, a swastika previously unknown to Russian money “a symbol of prosperity and prosperity”.

The 250 rubles denomination banknote against the swastika depicted the coat of arms of the new Russia - a double-headed eagle without symbols of monarchical power and crowns. The people called this image "stripped eagle" or "plucked chicken." The 1000 ruble banknote depicted the Tauride Palace in Petrograd, where the State Duma sat, and, as a result, such bills were unofficially referred to as "Duma money."

Ruble in roll

By August, 1917, inflation and the devaluation of paper money took on such proportions that for at least some functioning of the economy and government agencies it was necessary to increase the issue of paper bills several times. However, this was hampered by the complicated, time-consuming production technology inherited from Tsarist Russia. To cover the cash deficit, mass production of simpler bills was required.

In order not to invent a new technology, for printing simplified notes, it was decided to use the equipment for manufacturing so-called “stamps of consular mail” located at the Petrograd Mint, which previously paid state duty for the manufacture of visas and international passports. Thus, by decree of 23 of August 1917, a mass issue of "government treasury marks" of 20 and 40 rubles in denominations began. Since Alexander Kerensky, Social Revolutionary Party, was already the chairman of the government, these rubles were immediately nicknamed “Kerenks”.

The 20-ruble "kerenka" was printed in brown ink, the 40-ruble - red-green. On such money, in contrast to the rubles of the previous type, there was no number and series, an indication of the year of issue and the signature of the manager and the cashier. The small size of these bills, just 5 on 6 centimeters, made it cheaper to produce them - they were immediately printed in sheets of 40 pieces. When using such money, people simply cut the required amount from the sheet or cut it into strips, and then rolled it up into a roll. Due to the extreme simplicity of manufacturing, the market was immediately flooded with a mass of fake “kerenok”, and their mass issue just a few months before the end of 1917, led to an almost 5-fold increase in prices.

In order to cover the shortage of change coins to the brand money and royal paper pennies in circulation, the Provisional Government issued its stamps-money in denominations of 1, 2 and 3 pennies. Their obverse completely corresponded to the royal “marks”, and on the back, instead of the double-headed eagle, the figure of the nominal was put.

New people do not trust the money. Although due to the “money hunger”, that is, the shortage of banknotes in circulation caused by inflation, they actively used new money, but tried to make savings with large bills and old-fashioned money. "Romanov" or "Nikolaev" rubles, as the old bills began to be called, were valued much higher than the new ones.

As a result, in the summer and autumn of 1917, the large bills almost completely disappeared from circulation. The new money of the Provisional Government, mainly the “Kerenki” that quickly spread throughout the country, the population tried to use as a means of payment, and the largest old-style banknotes were used as a means of accumulation.

On the eve of the October Revolution, in November 1917, the total amount of paper money in circulation reached almost 20 billion rubles. During the 8 months in power, the Provisional Government issued more paper money than the government of the last king in the 32 month of World War II.

"Kerenki" from America

From the beginning of the war to 1 in March 1917, the purchasing power of the ruble decreased by 3 times, and over the 8 more than months of the Provisional Government's existence - by 4 times, by the end of October, 6-7 made up pre-war kopecks.

The government of Kerensky tried to solve the problem of filling the treasury with emergency measures. For example, since September 14, 1917 in Russia introduced a state monopoly on sugar (that is, from now on, all sugar trade was conducted only by the state). According to the calculations of Kerensky employees, this should have given 600 million rubles of annual income instead of the previous 140 million received from excise taxes. Also, the Provisional Government increased railway and postal and telegraph tariffs, excise taxes on tobacco and tobacco products several times and began developing a project for a sharp increase in utility bills.

In October 1917, the Ministry of Finance, in addition to the bread and sugar monopolies, developed a draft match, tea, coffee, tobacco and other state monopolies. Income only from the match and tea was planned in the amount of almost a billion rubles. The price of bread was officially increased by 100%.

At the same time, the Provisional Government developed new models of bills, which were to completely replace the former royal money. It was made even cliches for the state of the new type of credit cards. However, under the conditions of the growing collapse of the economy and the state apparatus, the government did not decide to print new money in Russia and sent secret letters to the ambassadors in Paris, London and Washington with the prescription: "Favor confidentially to find out the possibility of placing and issuing credit cards at coin factories."

As a result, the Provisional Government was able to order the manufacture of new Russian money in the United States. The first order for 60 million bills in 25 rubles and for 24 million bills of 100-ruble denominations was made at the end of September 1917. Before the end of this year, the United States was supposed to start producing monthly for Russia 3 million bills for 100 rubles and 7 million bills for 25 rubles.

All in all, in the USA, paper notes with 50 kopecks, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 rubles were ordered for printing. The price for a thousand pieces of Russian bills was 14 dollars 75 cents, not counting packaging, insurance, transportation and other overhead costs.

To speed up the manufacturing process, American specialists used ready-made drawings sent from Russia (for example, depicting the dome of St. Isaac’s Cathedral), supplemented with the coat of arms of the Provisional Government. The notes were printed with the date “1918 year”. However, this money came to Russia after the overthrow of the Kerensky government by the Bolsheviks Lenin - at the very end of 1919, the US State Department agreed to transfer part of the printed Russian bills worth 3 billion 900 million rubles to Admiral Kolchak's government. But Kolchak, in turn, did not have time to use them, since in the spring of 1920, he was defeated by the Red Army.

Information