People's hero of the First World War

And we will honor him - bye,

There is an army of Don in Russia, -

And the spirit of the powerful Cossack lives. ”

Georges cavaliers ... These words evoke in mind the images of dashing udaltsy, whose chest is decorated with gleaming silver and gold of St. George's crosses. Beauty and pride of the Russian army. Initially, the order of St. George was awarded only to generals and officers, but the grandson of the founder of the award, Alexander I, issued a decree commanding to extend this high honor to the lower ranks. 13 February 1807, a new "insignia of the order." For almost fifty years, the soldier’s cross had only one degree, but since the Crimean War 1856 of the year, four degrees have been instituted - the same was with the officer’s order.

The cross is small, but the reward for the soldier is great - the honor of "accrediting to the honorary order of the Holy Great Martyr George the Victorious." It was only possible to deserve it by accomplishing an outstanding act: capturing the enemy general, first to break into the enemy’s fortress, seizing the enemy banner, saving in the battle of his own banner or the life of the commander. St. George's crosses were more proud than any other awards. An ordinary warrior, who was barely remembered in his native village, earning the Cross of St. George, was made visible by a person, since rumors carried such fame far better than printed publications.

Cossacks have always been a real headache for any opponents of Tsarist Russia. Their cavalry, being part of the Russian army, visited the fields of almost all of Europe and Asia. Attacking three times the surplus enemy, hitting him from the rear, catching up the panic, disperse the wagon train, repel the guns - it was common for them. One of the most famous Cossacks - the Knights of the Cross of St. George - was Kuzma Firsovich Kryuchkov.

Information about his biography is very scarce. Kozma Firsovich was born in 1890 (and according to other sources in 1888) in the family of the Don Cossack Firs Larionovich. Kryuchkovs had a strong patriarchal family of Old Believers with strict moral principles. The boy spent his childhood in his native farm Nizhne-Kalmykovskiy, belonging to Ust-Khoperskaya stanitsa Ust'-Medveditsk district of Upper Don. In 1911, Kozma successfully graduated from the village school and was called up for service in the third Don Cossack regiment. According to the traditions dating back to the Middle Ages and lost to the beginning of the twentieth century in Russia (except for the Don regions and Siberia), at thirteen Kozma Firsovich was already married to a fifteen-year-old Cossack girl. Such marriages were explained both by the early growing up of people and by ordinary economic necessity — young workers were needed in the houses. Thus, at the time of departure for military service, Kozma already had two children: a boy and a girl.

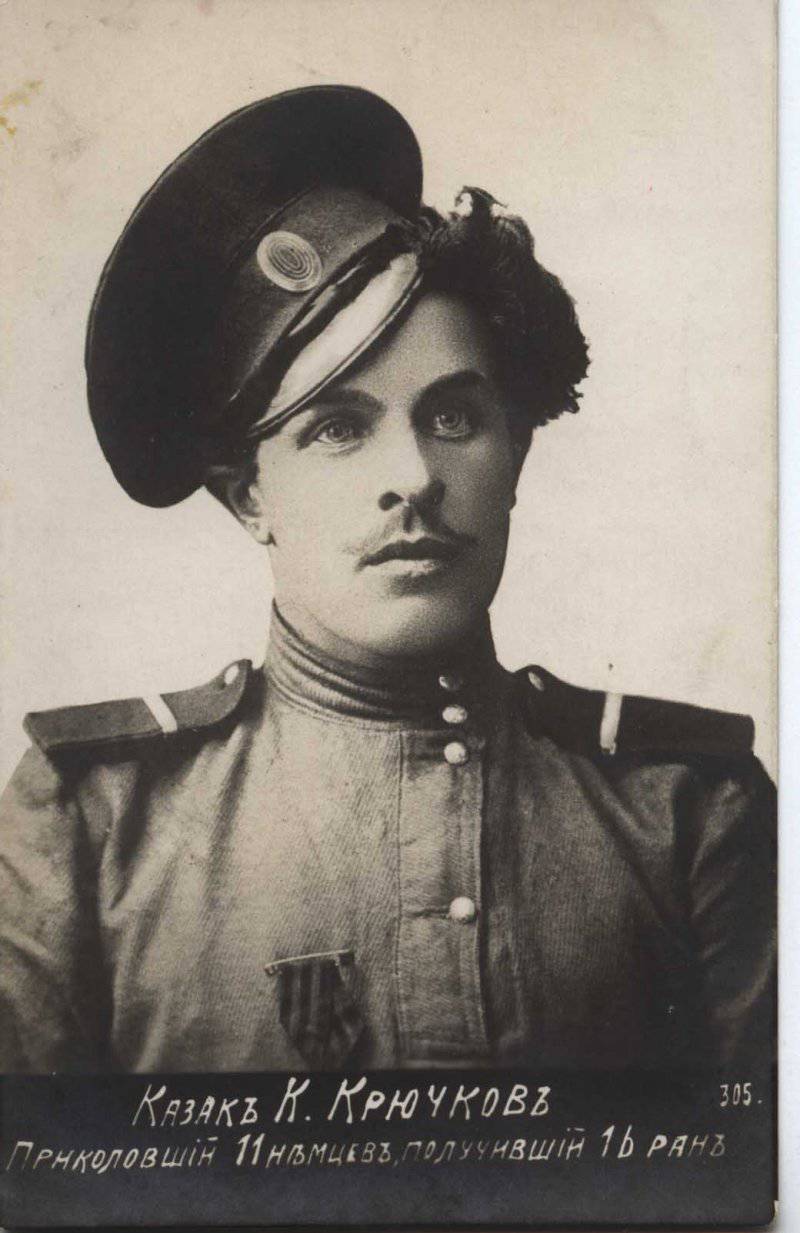

By the time the First World War began in 1914, the emperical (corporal) of the sixth hundred Third Don regiment Kozma Firsovich was already an experienced warrior, strong and agile, skillful and savvy. For the war, he, like every Cossack, was ready both morally and physically. I met her without fear, saw in it my main purpose, all that was part of his definition of "life." And according to one Cossack proverb: “Life is not a party, but not a funeral either.” According to the recollections of comrades, Kryuchkov was distinguished by a certain shyness and modesty, was open, sincere, and unusually bold. A whirlwind on his head, a strong build, a dexterous, mobile figure, all betrayed in him the true son of Don.

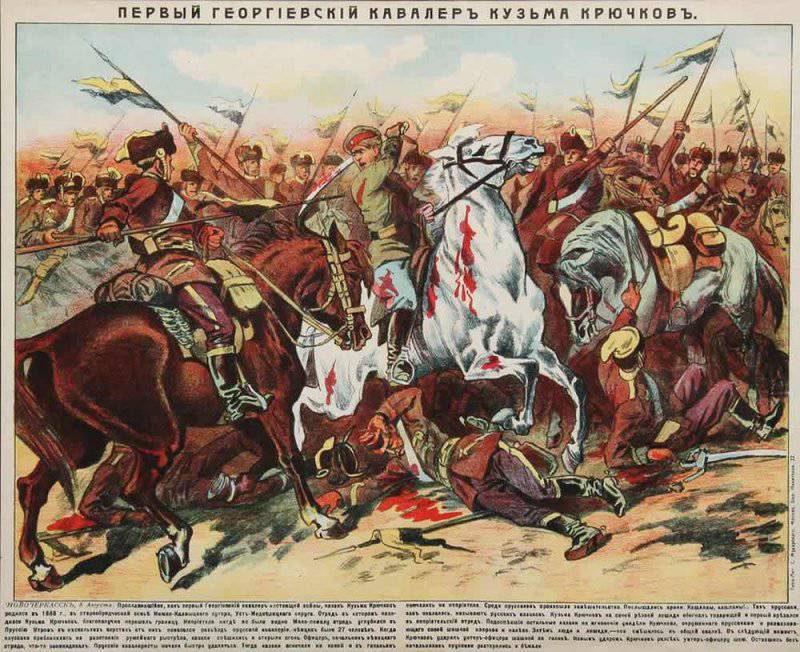

The regiment, which served as a brave Cossack, was stationed in the Polish town of Kalwaria. The main event of the whole life of Kozma Kryuchkov happened on July 30 of the 1914 year (August 12 in a new style) almost in his first battle clash with the enemy. On this day, a guard patrol consisting of four Cossacks led by Kryuchkov, when climbing up a hill, ran into a detachment of German cavalrymen numbering twenty-seven people (according to some information at thirty). The meeting was unexpected for both groups. The Germans were confused, but, having understood that there were only four Cossacks, they attacked. Despite the nearly sevenfold superiority, Kozma Firsovich and his comrades - Vasily Astakhov, Ivan Shchegolkov, Mikhail Ivankin - decided to take the fight. Opponents have become close and twirled in a deadly battle, the Cossacks covered each other, shredding the enemy according to old-fashioned covenants. At the first moment of the battle, Kryukov threw a rifle from his shoulder, but he too jerked the shutter too sharply and the cartridge was jammed. Then he snatched the sword, and at the end of the battle, when the forces began to leave him, he continued to fight with a pick snatched from the lancer’s hands. The results of the battle amazed the imagination - according to subsequent award documents and official reports, by the end of the battle twenty-two German horsemen were killed, two more seriously wounded Germans were captured and only three opponents survived to flee. The Cossacks did not lose a single person, although everyone had injuries of varying severity. According to the comrades, Kryuchkov single-handedly defeated eleven enemies, while he himself received over a dozen stab wounds, and his horse was no less affected.

So Kozma Firsovich described that fight: “At about ten o'clock in the morning we headed from Kalvaria to the Alexandrovo estate. There were four of us, climbing up the hill, came across a junction of twenty-seven people, including their officer and non-commissioned officer. The Germans climbed on us, we met them bravely, some were laid. Dodging, we had to separate. Eleven people surrounded me. Not tea to stay alive, I decided to sell my life more expensive. My horse is obedient, agile. He fired his rifle, but in a hurry he popped a cartridge, and at that time the German slashed his fingers. I threw a rifle and took up the sword. Got a couple of minor wounds. He felt that blood was flowing, but he understood that the wounds were not serious. For every one I pay with a death blow, from which a German lies forever a layer. Having laid several of them, I felt that with a sword it became difficult to work, picked up their pike and one by one put the rest. During this time, my comrades overcame others. There were twenty-four corpses on the ground, and not wounded horses scudded around in fear. Comrades received wounds, I received sixteen, but all empty, shots in the hands, in the neck, in the back. My horse received eleven wounds, but I rode six miles back on it. On August 1, General Rennenkampf arrived at White Olita, took off the St. George ribbon and pinned it on my chest. ”

For the perfect feat of Kozma Kryuchkov, the first soldier of the Russian imperial army received the St. George Cross of the fourth degree (the award number was 5501, an order from 11 (or 24 in new style) in August 1914.) "Soldier George" Cossack received in the hospital from the hands of army commander Pavel Rennenkampf, who was an experienced cavalry commander, who had a good reputation in Manchuria in 1900, and most likely understood a cavalry battle. The remaining participants were awarded St. George medals.

After five days in the infirmary, Kryuchkov returned to his unit, but was soon sent on leave to his native village. By the time of the return of Kozma Firsovich story about his feat managed to reach the ears of Emperor Nicholas II, it also outlined the actual all print publications of Russia. Overnight, the gallant Don Cossack became famous, becoming a living symbol of Russian military courage, a worthy heir to the epic warriors. Kryuchkov became the favorite target of photographers and even appeared in the newsreels. In 1914, all the pages of newspapers and magazines were filled with his photos. His face was painted on the cigarette boxes and patriotic posters, cheap popular prints and postage stamps. A steamer and a film were named after him, Repin himself painted a portrait of a Cossack, and some particularly fanatical fans went to the front to get to know him. The portrait of Kryuchkov was even on the wrappers of the “Heroic” candies produced at the Kolesnikov confectionery factory. The Moscow almanac "The Great War in Pictures and Images" reported: "The feat of the Cossack Kryuchkov, who became the first in a long series of awards for the outstanding feats of the lower ranks of the Order of St. George, arouses general enthusiasm."

In the acting army, Kozma was given a “thug” position of the chief of the convoy at the division headquarters. His popularity at this time reached its apogee. According to the stories of his colleagues, the whole convoy took part in reading the letters addressed to the hero, the division headquarters was littered with food packages. If their part was withdrawn from the front, the division commander informed the authorities of the city to which the troops were sent that Kozma Firsovich would be among them. Often after this, the warriors were met with music by a whole crowd of residents. Everyone wanted to see the glorified hero with their own eyes. In Moscow, the Cossack received a saber in a silver frame, and in Petrograd, Kryuchkov was presented with a saber in a frame of gold, the blade of which was covered in full praise. Soon, however, Kozma was tired of acting as an exhibit at the headquarters, he personally asked the authorities to transfer him back to the third Don regiment to fight the Germans.

His request was granted, and the brave Cossack found himself on the Romanian front. The fights were constantly going on here, the regiment fought it perfectly, Kryuchkov himself in a short time managed to prove himself a calculating, cold-blooded and intelligent fighter. And he always had the courage for three. For example, in the 1915 year, he, along with ten volunteers, attacked a detachment of the enemy that was stationed twice in the village. Part of the Germans was destroyed, many were captured alive, and among the abandoned things were found securities on the location of the German troops. Kozma was fired as sergeant, and "the general who came came shook his hand and said that he was proud to serve in one part with him." Soon the Cossack was given under the command of a hundred. In subsequent years, Kozma Firsovich repeatedly took part in major battles, often converged face-to-face with enemies, and was wounded more than once. So in one of the battles in Poland, he received three wounds at once, one of which threatened his life. Kozma had to undergo treatment for several weeks in a hospital near Warsaw. At the end of 1916, at the beginning of 1917, he was again injured and sent to a hospital in the city of Rostov. Here a unpleasant story happened to him, local crooks stole the Order of George and the golden award weapon from the hero. The incident was covered in Rostov newspapers. It was one of the last press references to Kozma Firsovich.

• Established by Catherine II "Imperial Military Order of the Holy Great Martyr and Victorious George" for officers;

• The insignia of the Military Order, called the "George Cross", also known as "Soldier George" (popularly sometimes called "Egoriy");

• St. George medal;

• St. George's weapons;

• Collective St. George awards;

• Commemorative awards with St. George's paraphernalia (usually, St. George's ribbon).

The first cavalier soldier George became a non-commissioned officer of the Cavalry Regiment, Yegor Ivanovich Mityukhin. He distinguished himself 2 on June 1807 in the battle with Napoleon’s troops at Friedland (near Kaliningrad). Before the revolution, the insignia of the Military Order was worn with dignity by many brilliant military leaders and commanders of the Red Army. For example, George Zhukov had two St. George crosses, Konstantin Rokossovsky - two St. George medals and St. George's cross, Rodion Malinovsky - two St. George crosses. Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev was the owner of a “full bow” (four crosses of St. George), Semen Mikhailovich Budyonny also had all degrees, and he received the fourth two times, the court deprived him of his reward for insulting the sergeant. I would especially like to mention the youngest Georgievskikh Kavalerov. Kazak Ilya Trofimov during the First World War went to the front as a minor volunteer and was awarded the St. George's Crosses of the third and fourth degree for combat exploits. A teenager, Volodya Vladimirov, went to war with his father-Khorunzhiy. He served as a scout, was captured, managed to escape and deliver important information to the command. For this, the brave guy received the St. George Cross of the fourth degree.

At the end of the war, Kryuchkov was the owner of two St. George crosses (the third is 92481 number and fourth degree), two St. George medals “For Bravery” (also third and fourth degrees), he rose to the position of the first officer rank among the Cossacks. When the February revolution broke out, the life of Kozma Firsovich, like many other Don Cossacks, changed dramatically. At this time, Kryuchkov had just recovered from his injuries and was discharged from the hospital. He was unanimously elected chairman of the regimental committee. But then there was a coup, the army collapsed in a short period of time, and there was a split among the Cossacks. Kuzma Kryuchkov, who was the most typical representative of the Cossacks from the Quiet Don, never for a moment thought about the question: "To accept or not to accept the revolution." Loyal to the Fatherland, the king, sworn in, Kozma took the side of the whites and, after the collapse of the army and the regiment, returned to 1918 in the year to his home.

However, the Cossacks did not succeed in a peaceful life in their native land. The Bolsheviks between the two divided and turned into brothers and friends, fathers and children. For example, Kryuchkov’s closest friend and member of the legendary battle, Mikhail Ivankov, decided to continue his service in the Red Army. And Koz'ma Firsovich himself during the Civil War had to confront another famous countryman - the future commander of the second Cavalry Army, Philip Mironov.

At the beginning of 1918, the Red Army came to the Don, which was withdrawing from Ukraine and oppressed by the Kaiser troops. Each detachment undergone various “contributions” to villages, requisitioned food, horses, household items. At the same time, baseless executions took place. The hastily created committees of the rural poor also arbitrarily and robbed the people. In such conditions, the number of supporters of the new government sharply decreased, but the disarmed and demoralized Cossacks were slow, as if waiting for some kind of miracle. At that moment they were not brought to the extreme degree of despair. In this regard, for the first six months, only partisan troops fought against the advancing on Novocherkassk, Taganrog and Rostov. At the end of April, 1918-th Kryuchkov, together with his friend Alekseev, created a detachment of seventy people, armed with swords and two dozen rifles. With such miserable forces, Kozma Firsovich repeatedly tried to repel the Ust-Medveditskaya village, in which well-armed units of the Red Army under the command of Mironov, a former military sergeant (later executed by the Bolsheviks), constantly supported by passing troops.

By the beginning of May, the 1918 of the year of the atrocities of the Reds multiplied, and it was then that the Cossack marchers poured into the steppe. The Veshensky uprising grew, allowing Kryuchkov and Alekseev to undertake a new attack on the district village. 10 May at four o'clock in the morning a detachment of Ust-Khopertsev under the command of Kryuchkov flew at the red pickets. The bulk of the team under the command of Alekseeva attacked the village from the front. The battle was bloody, the village passed from hand to hand a couple of times, but the whites finally won. “Don Wave” wrote: “... during the capture of Ust-Medveditskaya, Kozma Kryuchkov - the Cossack of the village of Ust-Khoperskaya and the hero of the last war with the Germans who shot a picket of six people — distinguished himself.” For the successful attack Kryuchkov was fired into a cornet. From that moment on, he became not just an active participant in the uprising, but one of the respected leaders. The rank and file Cossacks undividedly trusted him - the cornet of the thirteenth Ust-Khopersky equestrian regiment of the Ust-Medveditsa division. In addition, the presence of a famous hero in the ranks of whites was the best campaign for recruiting volunteers in the villages. Kozma Firsovich himself continued to fight skillfully, except for heroism and courage, according to the recollections of his commanders, was distinguished by high moral character. The Cossack did not tolerate looting, and rare attempts by his subordinates to get hold of at the expense of "trophies" from the local population or "gifts from the Reds" stopped them with a whip.

No matter how bravely the Cossacks fought, no military mastery, no heroism could defeat the force rolling on the Don. At the end of the summer of 1919, whites began their retreat on this territory. Ust-Medveditskaya cavalry division fought and retreated, fought fierce battles, experienced wars fought on both sides, past the fire of World War. That, going on to counterattacks, then defending themselves, taking losses and capturing prisoners, the division covered the withdrawal of the Don army. Kryuchkov headed one of the units of the rearguard, restraining the Reds near the village of Lopuhovka of the village of Ostrovskaya. By this time he had already received the rank of centurion. Several Cossacks, including Kozma Firsovich, were not far from the bridge across the Medveditsa River. The bridge itself was considered “no one’s,” but it was a great place to contain the advancing Bolsheviks. By the time Kryuchkov’s squad arrived in time for him, the Reds vanguard had already moved to the other side. Under the cover of two machine guns, soldiers were digging in. Perhaps Kryuchkov decided to use this moment in order to rectify the situation. There was no time to explain what was already planned, he pulled out a sword and ran to the bridge, throwing the rest over his shoulder: “Follow me, brothers. Beat the bridge. And to meet them on the bridge moved about forty people. The Cossacks slowed down, got up and red, watching as only one person fleeing the attack on them. According to the stories, Kozma Kryuchkov safely reached the first machine-gun nest and chopped up the entire calculation, after which he was shot from the second machine-gun. The battle nevertheless began, in the confusion the comrades managed to pull out the hero. Bullets riddled Cossack. Three hits fell into his stomach, so Kozma Firsovich suffered a lot and could not move. The wounds were so terrible that it became clear to everyone - the death of a brave man is inevitable. To the doctor’s attempt to bandage him, Kozma courageously replied: “Do not spoil the doctor’s bandages ... they are not enough ... and I won back.” Dying he stayed in the village. But what his colleagues wrote when they were in emigration: “In the autumn of 1919, Kryuchkov, heading the guard of the Cossacks, without an order, he arbitrarily tried to dislodge the Reds from the opposite shore near the stanitsa of Ostrovskaya. Having let them go, the Reds shot them from a machine gun. ” Kozma Kryuchkov died from wounds 18 August 1919-th year. According to other - not documented sources - he was wounded shot red. And in one absolutely unthinkable story it is told that Budyonny personally dealt with him. The body of Kozma Firsovich was buried in the cemetery of his native village.

Kuzma Kryuchkova’s name doesn’t mean anything to most people in Russia. This is understandable, after the revolutions of 1917, all information about the heroes of imperialist times was consistently destroyed. Not a single Cossack was so lightly lifted up on the pedestal of national glory ... And not a single Cossack was so slandered under Soviet rule. They made a mockery of his name, his actions were declared a propaganda lie, a fiction ... The Cossacks, on the whole, were perceived by the Soviet authorities only as "suppressors of the revolution" and "the main support of tsarism." The new ruling elite did not stop at the destruction of the Cossacks as a unique military class, she tried to erase all the memory of him.

Such a reassessment of values by new generations is not at all an invention of the past century. They copied history and debunked old idols when changing the ruling elite always and not only on the Russian land. In particular, during the reign of the Cossacks, the memory that they are an independent people was also etched (and not without success). The court chroniclers began to distort the ancient history of the Cossacks after the end of the Patriotic War of 1812. This was done as an attempt to combat their increased separatism and authority.

The Cossacks have a wonderful saying: “True lie does not take either lies or rust.” Glory is immortal, and in this we are constantly convinced. Unfortunately, today at a fairly large once (four kilometers long), Kozma Kryuchkov’s native farm did not stand a single house. The cemetery was abandoned and overgrown with grass, where the grave of the legendary Cossack, the hero of the First World War, which was lost among the weeds, is located. The memorial cross on it is also not preserved. Nobody comes here now, and descendants of those who have found rest in this place do not come, and there are thousands of graves - thousands of torn strings of memory.

Information sources:

http://shkolazhizni.ru/archive/0/n-12708/

http://don-tavrida.blogspot.ru/2013/08/blog-post.html

http://kazak-center.ru/publ/1/1/62-1-0-57

http://www.firstwar.info/articles/index.shtml?11

Information