Military cooperation between Italy and the USSR in 1933-1934: strengthening the partnership in the face of the threat of a growing Germany

There is a fairly widespread opinion in historiography that the union of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany was predetermined, but in fact this is not entirely true. Despite the fact that Mussolini welcomed the conquest of power by the National Socialists, he was clearly in no hurry to meet them halfway, and it would be incorrect to say that Italy was initially aimed at achieving an alliance with Germany.

American historian Joseph Calvitt Clark, in his remarkable work “Russia and Italy Against Hitler: The Bolshevik-Fascist Rapprochment of the 1930s,” notes that Hitler’s rise to power and rise Germany's economic and military power, to put it mildly, upset the European state system and threatened to change the balance of power that had been achieved in Europe during the interwar period [1930].

Both Moscow and Rome recognized the danger of the situation, since for Moscow the rise of the Nazis to power marked the beginning of the decline of ties with Germany (which was an important element in Soviet foreign policy), and for Rome the changes threatened Austria, the Alto Adige region and the aspirations of Italy in the Balkans. Hitler and Nazism were not the only catalysts for improving ties between Moscow and Rome, but they played a decisive role [1].

The years 1933 and 1934 were generally critical for European diplomacy, as statesmen tried to understand exactly what Hitler was and how best to deal with him and a resurgent Germany. The rapprochement between Italy and the Soviet Union in this ensuing chaos of diplomatic initiatives is of particular interest, so it is worth dwelling on in more detail. First of all, the issue of military and diplomatic contacts between the two countries will be considered.

Foreign policy of Italy and the USSR: reasons for rapprochement

Speaking about the policies of fascist Italy in the 1920s, the famous researcher of Italian fascism R. De Felice notes that Italian policy in these years was generally cautious and reasonable in its own way, which explains the judgment expressed many years later, for example, by the American Secretary of State Stimson:

- writes De Fliche. That is, Mussolini, despite the revisionist rhetoric, tried to maintain ties with the Versailles system and give Italy the role of a great power.

Researcher of fascist military policy L. Cheva believes that until 1934, the Italian military command did not have prepared plans for a major war; military planning was limited to the level of individual armed forces. Moreover, the first concrete documentation regarding military planning, which relates to September-October 1934, in connection with the Austro-German crisis, provided for participation in the war against Germany on the side of France and Great Britain [2].

In the 1920s, Italy concentrated on relations with Danube and Balkan Europe, Turkey and Soviet Russia. In the first months of 1924, Italy recognized the new Soviet regime and concluded two agreements with Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, which is why in Italian political circles they began to talk about the Rome-Belgrade-Moscow axis. The goal of that policy was not only to use the USSR as a counterweight to Great Britain, but also to strengthen Italian positions in relation to France, which initiated the Little Entente [2].

In order to achieve its goals, Italy sought to involve the USSR in European affairs. As historian V.I. Mikhailenko notes, from the end of 1925 Mussolini assigned an important role to the USSR in his policy of revising the Treaties of Versailles [2]. In turn, Soviet diplomacy showed an interest in keeping Italy among those countries that resisted Germany.

On September 2, 1933, a Soviet-Italian treaty of friendship, non-aggression and neutrality was signed. The rapprochement between Italy and the USSR occurred on the basis of the similarity of positions in preventing the Anschluss of Austria. The Soviet government sought to show the groundlessness of Italian objections to the Eastern Pact, based on the premise that the topic of the day was the prevention of the German danger [2].

The Austrian problem seriously aggravated Italian-German relations - it even got to the point that when in July 1934 the Austrian Nazis tried to carry out a coup d'etat, during which the Austrian Chancellor E. Dollfuss, a personal friend of the Duce, was mortally wounded, the enraged Mussolini responded to this with concentration Italian troops near the Austrian border and declared his determination to preserve the independence of the Austrian Republic [5].

Soviet leaders tried to refute the suspicions of the fascist leadership that the Eastern Pact was directed against Italy. They spoke out against establishing any connection between the Eastern Pact, on the one hand, and the Mediterranean Pact, the Little Entente, on the other.

In 1934, the Soviet plenipotentiary in Italy V. Potemkin wrote in his report:

Military contacts between the USSR and Italy in 1930-1934

The beginning of military-technical cooperation between the USSR and Italy can be considered the call on August 8, 1924 of the OGPU marine border guard patrol vessel “Vorovsky” to the port of Naples. In response, in 1925, three Italian destroyers - Panther, Tiger and Lion - visited Leningrad on a friendly visit. And already next year, within the framework of agreements between the governments of the USSR and Italy on military exercises, 4 royal destroyers entered the Black Sea fleet.

Subsequently, contacts continued - here it is worth noting the first flight of a large Italian squadron to the USSR under the command of Italo Balbo, which took place in 1929, and the repeated visits of Soviet delegations to Rome. In the late 1920s and early 1930s. Several Soviet units were constantly working in Italy aviation missions that visited various Italian aircraft factories in order to familiarize themselves with the achievements of Italian designers and conclude contracts for the supply of aircraft and aviation equipment [7].

In the 1930s, due to the rapprochement between Italy and the USSR, these contacts became more intense. The Soviet Union assigned a special role to technical cooperation with Italy, which during this period was the unrecognized leader in the field of creating naval equipment and weapons. In August 1930, while on vacation in Sochi, I.V. Stalin, meeting with the head of the naval forces (MS) R.A. Muklevich, pointed out the need to immediately send a group of naval specialists to Italy to become familiar with the achievements in the technology and tactics of the Italian fleet. At the same meeting, the issue of ordering an Italian-built cruiser was discussed [6].

In 1930 and 1931, Soviet specialists visited Italy more than once. After these visits, Muklevich wrote in a report:

As a result, it was decided to begin purchasing weapons from Italy. It was with Italian companies producing naval products that the state and military bodies of the USSR interacted most fruitfully, multifacetedly and comprehensively. As a result of this cooperation, the Soviet Union acquired samples of new naval anti-aircraft artillery, rangefinders, periscopes, and torpedoes. Help was also received in the construction of cruisers and destroyers [6].

The Italo-Soviet economic agreement of May 6, 1933 contributed to the further development of commercial relations between the two states and cleared the way for political negotiations. These negotiations culminated in the Pact of Friendship, Neutrality and Non-Aggression of September 2, 1933.

When signing it, Soviet diplomat V. Potemkin briefly emphasized the importance of the pact not only for its signatories, but also for peace in Europe. In response, Mussolini confidently stated that the pact represented "logical development of the friendship policy" [1]. Celebrating the signing of the pact on September 2, Soviet newspapers rejoiced at this fact and noted that Italian fascism was different from German Nazism, and assured readers that ideology should not interfere with the growing friendship between Rome and Moscow [3].

In anticipation of the visit to Rome of Foreign Commissioner Maxim Litvinov in December 1933, three Soviet ships, the cruiser Red Caucasus and the destroyers Petrovsky and Shaumyan, left Sevastopol on October 17, arriving in Naples thirteen days later. The Soviet press emphasized that the naval visit demonstrated the strong friendship that existed between the Italian and Soviet military and civilian authorities [3].

In Berlin, such maneuvers were viewed with some concern, since the signing of this pact and accompanying military contacts exacerbated Rome's opposition to Nazi plans regarding Austria.

In the summer of 1934, just as Nazi provocations in Austria were gaining momentum, three Soviet military aircraft visited Italy in response to Italo Balbo's flight to Odessa. The planes took off from Kyiv on August 6 and flew to Rome via Odessa, Istanbul and Athens. There were thirty-nine people on board, including high-ranking military officials and civil aviation technicians [3].

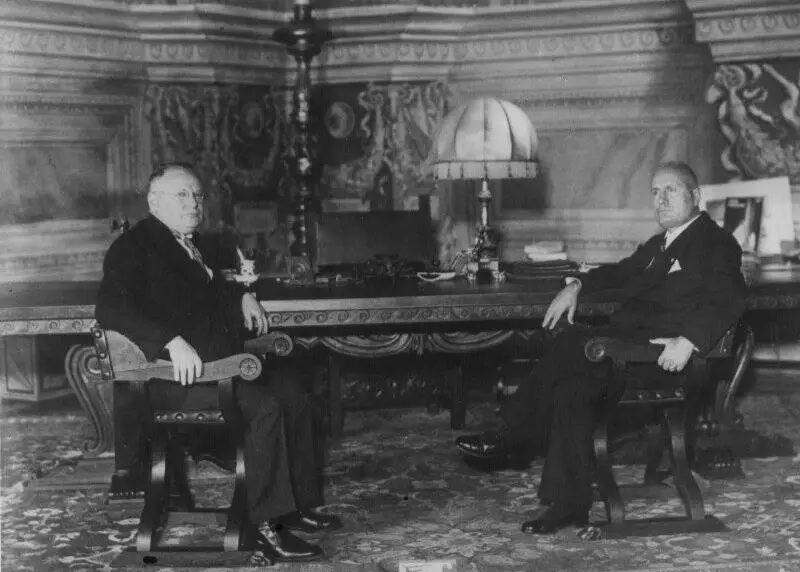

On August 8, Mussolini, together with General Giuseppe Valle and Deputy Secretary of State Fulvio Suvic, received the Soviet mission at the Palace of Venice. After the Duce praised Russian aviation, representatives of the Soviet mission shouted “hurray” three times [3].

In the fall of 1934, Moscow and Rome even exchanged observers at their annual military maneuvers. Hoping to conclude contracts for the supply of military goods to the USSR, the Italians took representatives of the Soviet mission to various military and industrial facilities. In turn, Italian military experts observed the maneuvers around Minsk from September 6 to 10 - the progress of the Red Army impressed the Italian delegation.

In general, for Rome, contacts with the Soviet Union were important both from an economic and political point of view, since Italy wanted to persuade Hitler to moderate and, in particular, to prevent the Anschluss. In turn, the Soviet Union needed military goods, equipment, ships, etc., and also sought to ensure that Italy did not get closer to Germany.

Conclusion

To summarize, it should be noted that military contacts, consultations and technical cooperation significantly advanced the Italian-Soviet political rapprochement of 1933-1934. The apparent incompatibility and even hostile nature of the ideologies, apparently, should have interfered with mutually beneficial relations, however, both Italy and the USSR, as Joseph Calvitt Clark rightly notes, overcame this drawback; ideological differences did not prevent rapprochement [1].

Politicians assessed the Soviet-Italian pact differently: some viewed it as directed against French hegemony in this region and believed that, with the mediation of Italy, it could serve as a means of Soviet-German rapprochement, others, on the contrary, saw it as an omen of the future Italian-Soviet -French cooperation against Germany.

Clark believes that Italy could play an important role in the formation of the nascent collective security coalition designed to contain a rising Germany. Until about 1936, it was the only power that had both the will and the means to stop German expansionism in its tracks through direct political and military intervention in Austria against the Anschluss [3].

However, this dilapidated structure collapsed after 1935, when Italy went to war in Ethiopia - despite the victory achieved (which was essentially a Pyrrhic victory), its political position worsened and its room for maneuver decreased. At the same time, Italian-Soviet relations deteriorated somewhat (although the volume of trade turnover remained the same), but they finally deteriorated when Italy and the USSR supported different sides of the conflict in the Spanish Civil War.

Nevertheless, Italy, both before the signing of the “Steel Pact” and for some time after its signing, tried to pursue a policy of maneuvering, negotiating with London and Paris and not closing the door to contacts with the USSR. As the historian V. Mikhailenko rightly points out, for the fascist leadership the conclusion of the “Steel Pact” did not predetermine the choice of an ally in the big war, which was proven by the announcement of the policy of non belligeranza (“non-belligerent side”). The final choice of an ally depended on which great power or bloc of powers Mussolini assessed as the future winner of the war [2].

Использованная литература:

[1]. J. Calvitt Clarke III. Russia and Italy Against Hitler: The Bolshevik-Fascist Rapprochement of the 1930s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991.

[2]. Mikhailenko, V. I. “Parallel” strategy of Mussolini: Foreign policy of fascist Italy (1922-1940): in 3 volumes / V. I. Mikhailenko. – Ekaterinburg: Ural Publishing House, University, 2013

[3]. J. Calvitt Clarke III. Italo-Soviet military relations in 1933 and 1934: manifestation of cordiality. Paper Presented to the Duquesne History Forum. Pittsburgh, PA. October 27, 1988

[4]. De Felice R. Mussolini il duce. Gli anni del consenso, 1929-1936. - Torino: Einaudi, 1996.

[5]. Svechnikova S.V. Italian-German relations in 1936-1939. : ideology and practice.

[6]. Fedulov S.V. Military-technical cooperation between the USSR and Italy in the creation of naval equipment and weapons in the 1930s. Historical, philosophical, political and legal sciences, cultural studies and art history. Issues of theory and practice: Scientific-theoretical and applied journal: Scientific-Theoretical and Applied Journal N. 3 (41) Part 2 /2014. pp. 202 - 206.

[7]. Dyakonova P.G. Negotiations on the purchase of FIAT aircraft and testing of captured CR.32 aircraft in the USSR // Historical journal: scientific research. – 2019. – No. 3.

Information