Forgotten victory: about the Soviet bomber raid on Taiwan. Chinese knot

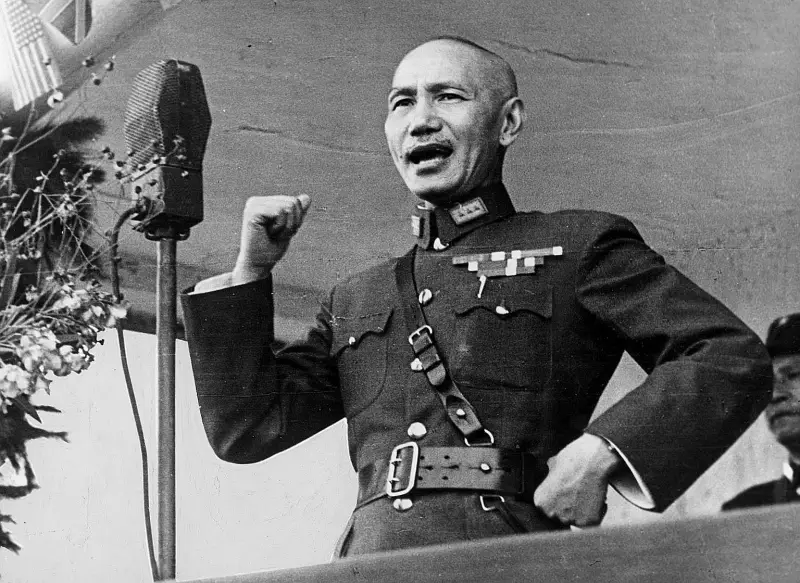

Chiang Kai-shek.

In the grip of the economic crisis

Let's continue what we started in the article "The samurai go on the warpath" conversation.

In the early 1930s, Japan, having barely overcome the consequences of the Great Kanto Earthquake, faced a new problem in the form of an economic crisis.

The number of unemployed people amounted to 3 million people by 1931, there was a reduction in exports on the foreign market and a decrease in the purchasing power of Hirohito’s subjects on the domestic market.

At the same time, the empire was experiencing a demographic explosion: during the Meiji era, the population almost doubled: from 33 million to 53 million, by 1930 exceeding 90 million people.

At the same time, against the background of the above data, it is worth giving credit to the government for solving the food problem:

However, rapid population growth in a capitalist society experiencing an economic crisis gives rise to the problem of “extra” people.

A small step aside: the same thing happened in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, when, against the background of the growth of the rural population, P. A. Stolypin began to destroy the community, but not all peasants managed to turn into strong owners - an analogue of the American middle class, the formation of which This is how Pyotr Arkadyevich dreamed.

The negative – in the eyes, of course, of those in power – energy of the unemployed and generally dissatisfied sections of the population can be channeled in three ways.

First: creating a sufficient number of jobs, which seemed unprofitable to a considerable part of entrepreneurs.

The second is emigration. And where could the Japanese proletarian go? To China? There were plenty of restless people there.

Unless the government would create a maximum favored nation regime for workers in the Middle Kingdom. Emigration to Korea somewhat smoothed out the problem, although not completely.

And here we come to the third way - external aggression.

It partly solved not only the problem of “extra” people, but also met the interests of the zaibatsu, who sought to expand the sales market, access to raw materials and cheap labor.

Common sense in the shadow of militarism

However, not everyone in the government circles of the empire shared expansionist plans.

A supporter of Japan's non-aggressive foreign policy was temporarily - from 1930 to 1931 - the head of its government, Kijuro Shidehara, known for his pro-American sympathies.

For obvious reasons, his course did not attract support from the zaibatsu. In fact: where can they find sales markets, except in the Middle Kingdom?

In the previous article, I noted the Japanese ousting the British from the markets of their own dominions, but this process could only bring results in the long term. And that’s not one hundred percent. For Japanese goods, in addition to English ones, had to withstand competition with American ones.

So Manchuria inevitably became the focus of attention of Japanese financial and military circles, which could not but cause concern, in addition to the USA and the USSR, also in Great Britain, France and the Netherlands. Not to mention Kuomintang China.

One of them concocted the “Tanaka memorandum,” which is considered to be the original in the PRC by a number of researchers. It is unlikely that he is. In any case, its original source has not been discovered.

But something else is important: the memorandum, albeit fabricated, reflected the views of a significant part of the Japanese elite, who believed that it was necessary for the prosperity of the empire to capture China.

The personality of Lieutenant General Giichi Tanaka is interesting. We would like to talk about it separately. For now, I’ll limit myself to a remark: while an assistant military attache in what was then Tsarist Petersburg, Tanaka learned Russian, was keenly interested in Russian culture, and attended liturgy every Sunday.

All this, of course, did not prevent him from remaining a champion of Japan’s prosperity at the expense of its neighbors—China, first of all. Moreover, Tokyo’s foreign policy seemed to be in a vicious circle: Shidehara’s attempt to avoid confrontation with the United States ruled out an invasion of China. Both the military and the zaibatsu insisted on the latter.

And as if responding to their aspirations, the officers of the Kwantung Army staged the Mukden Incident. In Tokyo, they supported the initiative, dressed in the form of a provocation, the goal of which was to take control of Manchuria, and Shideharu was sent into retirement. True, he was replaced, oddly enough, by Inukai Tsuyoshi, a champion of a non-aggressive course in the international arena.

Here, not only to the officers of the Kwantung Army, but also to the military personnel located in the metropolis itself, the diplomatic negotiations with the Chinese began to seem protracted: Inukai tried to resolve the Mukden incident through negotiations.

And the prime minister was shot dead as a result of a failed military coup attempt. However, the reason for the murder was not so much Inukai’s desire to prevent the build-up of Japanese aggression in Manchuria, but rather the London Treaty signed by the empire in 1930, which further tightened the regime of restrictions on naval weapons, adopted eight years earlier in Washington.

Actually, it was precisely the confrontation with the White House, and not the poorly trained units of Zhang Xueliang, one of the leaders of the Kuomintang, who opposed the Kwantung Army - one of the leaders of the Kuomintang, but who did not get along with Chiang Kai-shek and therefore did not receive timely military assistance from him - that Inukai feared.

Moscow in search of a compromise

Reminiscent of the provocation staged by the Nazis eight years later in Gleiwice, the Mukden incident became the starting point for the precise Sino-Japanese War.

Without encountering serious resistance, units of the Kwantung Army quickly occupied Manchuria.

Already in October 1931, according to historian V.G. Opolev, the Japanese ambassador to the USSR declared the undesirability of sending Red Army units to the Chinese Eastern Railway, because otherwise Tokyo would take appropriate protective measures; and, in addition, it accused the Kremlin of supplying weapons to the Chinese. We're talking about the Kuomintang. The communists also received help, but through the Comintern.

The Japanese's reproach was not without validity when viewed through the prism of their interests. Let me clarify: we were talking about illegal - they would become legal only in 1937 - supplies of weapons to the Kuomintang, which Moscow saw as the only force at that time capable of stopping the advance of the samurai deep into the Celestial Empire and their exit to the border of the USSR.

And Chiang Kai-shek himself did not hide: it is impossible to effectively fight the aggressor without Soviet military assistance. He was also a pragmatist, although he couldn’t stand communists – both Soviet and Chinese.

And this despite his trip a year before the death of V.I. Lenin to the Soviet Union, a warm meeting and negotiations with L.D. Trotsky, who headed the Revolutionary Military Council at that time.

At first, arms supplies from Moscow were carried out to individual units of the Chinese army and, since they were not formalized, were not advertised, so as not to irritate the Japanese.

If I'm not mistaken, the photo shows Chiang Kai-shek's wife Soong Meiling with soldiers of the Kuomintang army.

In general, as, in my opinion, the historian R. A. Mirovitskaya rightly writes:

Although Tokyo could not do without irritation, since Chinese units often retreated to the territory of the USSR, and this happened without prior agreement with our border guards.

And then the samurai began to travel around the Chinese Eastern Railway and, without much ceremony, grabbed and beat, sometimes to death, the Soviet citizens serving it. Moscow had to think about selling the road, since the success achieved in the confrontation with Xueliang’s troops during the 1929 conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway was problematic to repeat against better trained and equipped Japanese.

Like Tanaka, Xueliang deserves a separate discussion - both as perhaps Chiang Kai-shek’s main rival in the struggle for power in the Kuomintang, and as his personal captive for many years.

In general, the tension in the dialogue between Moscow and Tokyo occurred against the backdrop of the rapid build-up of the empire’s military presence in Manchuria, where by 1934 the Japanese had built 40 airfields and 50 landing sites, and put into operation the region’s railway communication with Korea.

This allowed them to quickly transfer troops to the continent, and by the mid-1930s reach the Great Wall of China and occupy Shanghai.

The civil war that flared up in China between the Communists and the Kuomintang played into the hands of the samurai. That is why Chiang Kai-shek did not declare war on Japan in 1931, considering it sufficient to sever diplomatic relations with it and file a complaint with the League of Nations.

At the same time, the Chinese government appealed to the army and the population to refrain from resisting the aggressor, naively counting on receiving compensation from Tokyo for the damage caused by the Kwantung Army.

The subjects of Amaterasu’s “descendant” parted with the League of Nations in 1933 without regret, however, not because of the complaints of the Kuomintang leader, but because of the organization’s refusal to recognize the puppet Manchukuo.

It is noteworthy that, while condemning the aggression against China, the League of Nations did not impose economic sanctions against Japan. However, Tokyo should have been more concerned about the reaction of the United States, formulated within the framework of the “Stimson Doctrine” of 1932, the essence of which was expressed in non-recognition of the samurai occupation of China.

On the seemingly cloudless Tokyo horizon loomed what the sober-minded Shidehara so feared: the prospect of a conflict with the economically more powerful and richer, in terms of the presence of raw materials strategically important for a modern war, the United States, which, obviously, would be joined by Great Britain, which still retained the status of the largest colonial power.

On top of that, in 1933 Moscow and Washington established diplomatic relations, which, in the eyes of the far-sighted part of the Japanese political elite, preceded the consolidation of their efforts in opposing imperial aggression against China, in the expansion of which both powers were not interested.

And as confirmation: in the same year, a Soviet embassy was opened in Nanjing. Moreover, there is an interesting detail: D.V. Bogomolov, who headed it, reported to Moscow about conversations widespread in Chinese society regarding the approaching Soviet-Japanese war.

We did not intend to fight the Japanese, but we increased assistance to the Kuomintang in the second half of the 1930s, due to the increased threat to the security of our allied Mongolia.

I would like to note Tokyo’s desire to use Russian emigration in the form of the gangs of Ataman G. Semenov for its own purposes, creating the “Asano” brigade on their basis.

In general, the danger from the White Guards should not be underestimated. It's the second half of the 1930s. In the roar of industrialization and, yes, sometimes with excesses, collectivization, I.V. Stalin was preparing the country for the Second World War, the shadow of which was already hovering over Europe, dozing under the Versailles-Washington blanket.

And then L. D. Trotsky, offended by everyone and everything, scribbled various things from Coyoacan, which he had chosen in 1937.

Did he have supporters in the middle and senior command of the Red Army?

I don’t presume to judge, but there were enough commanders who owed their careers to the “Lion of the Revolution” when he was the People’s Commissar for Military Affairs, just like yesterday’s white officers who, after the defeat in the Civil War, went to serve in the Red Army.

And for Moscow it remained completely unclear: how they would behave in the event of an aggravation of the situation on the border with Poland or Manchukuo, as well as against the backdrop of a turbulent military-political situation in Siberia and Central Asia?

The above context explains Moscow's close attention to the Far East. In the context of the memorable events of the War Alarm of 1927 and unfinished industrialization, the USSR sought not to aggravate relations with Japan, taking a number of steps in this direction.

Namely: the Kremlin offered Tokyo to buy the Chinese Eastern Railway at a favorable price for it - we simply did not have enough military resources to hold the road with the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Kwantung Army; and also conclude a non-aggression pact with Japan.

They managed to sell the road, albeit at a reduced price, and after long delays, but Tokyo refused to conclude a non-aggression pact. Although in this matter the Soviet Union expressed its readiness to make serious concessions.

So, according to the historian K. E. Cherevko:

And even more than that, the USSR refused to allow a League of Nations commission to pass through its territory to find out the reasons for the invasion of Japanese troops into Manchuria.

Japanese army.

It seems that the Kremlin was aware of the futility of the mission and did not want to provide Tokyo with another reason to aggravate relations.

The sky over Taiwan is getting closer

Nevertheless, Soviet-Japanese contradictions grew and ultimately led, in 1937, to a series of serious military clashes along the Amur border, the most famous of which was the Annunciation Incident.

That same year, Japan began a full-scale war with China; a real threat of invasion of the Kwantung Army into the Mongolian People's Republic was created: its “overhang” over the left flank of Lieutenant General Kenkichi Ueda could not but cause concern to his headquarters; as the events of 1945 showed, it was completely justified.

In this situation, the Kremlin, which was in dire need of an ally in the Far East, decided to provide the Kuomintang with more effective military-technical assistance and in the same 1937 concluded a non-aggression pact with it.

Diplomatic relations, broken after the conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway, were restored at the initiative of the Chinese side back in 1932. And Moscow has already officially begun supplying weapons to the Middle Kingdom.

Under these conditions, the prospect of an air strike on Taiwan turned from hypothetical to real.

The ending should ...

Использованная литература:

Meshcheryakov A. N. Demographic explosion of Japan during the Meiji period

Opolev V. G. The role of Chiang Kai-shek in Soviet-Chinese relations (issues of domestic historiography

Mirovitskaya R. A. Relations between the USSR and China during the crisis of the Versailles-Washington system of international relations (1931–1937)

Michurin A. N. Soviet-Chinese relations on the eve of World War II

Cherevko K.E. Hammer and sickle against the samurai sword. M., 2003.

Information