Constantinople. Assault 1203

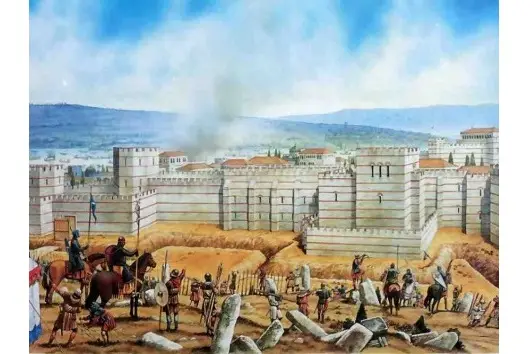

Siege of Constantinople by the Crusaders. 1204 Peter Dennis. Osprey Publishing

Enemy at the gate

In June 1203, near the city of Abydos (modern Canakkale), the collection of all ships and vessels of the crusaders began. At this point in August 717, Maslama's Arab army crossed the strait to besiege Constantinople.

Their next stop was at the monastery of St. Sebastian, modern Yeşilkoy district, 12–13 km (three French leagues) to the walls of Constantinople.

Now the arriving pilgrims saw Constantinople, which shocked them, Villehardouin writes:

Here there is a military council, at which, without the cunning Venetian Doge, everything would have been completely different or, as usual, during the sieges of New Rome. The enemies would have trampled before the city walls of Theodosius, and then, with the loss of resources, would have been forced to retreat.

But the Doge proposed to strike from the sea, and before that to capture the Princes' Islands and the Asian coast in order to provide themselves with food. This plan was accepted.

Prince's Islands. Photo by the author.

On June 24, 1203, the entire Crusader fleet passed the southern walls of Constantinople, and the entire city came running to see this spectacle. Moving north along the strait, they passed Constantinople on the right and landed in Chalcedon (on the Asian side of the Bosphorus), at the Rufian imperial palace, where they pitched tents and provided themselves with food.

Kadykoy, once Chalcedon. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

After a short rest, they took up a position much closer to the city. The naves and cargo naval fleet moved to Pereia harbor (modern Kabatash) below Diplokion (this is the modern Besiktas district). Here the Venetians saw and then reproduced in their city two columns in Piazza San Marco.

Photo of two columns. Piazza San Marco. Venice. Photo by the author.

And the dromons of the pilgrims stood on June 26, 1204, opposite the entrance to the Golden Horn, on the Asian coast in Scutari (Chrysopolis, modern Uskudar), where another imperial palace was located. In the region of Pere or Galate (modern Galata) there were clashes between knights and the “knights” of the Greek emperor, the Roman horsemen.

Üsküdar. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

A knight from Lombardy, Nicolas Roux, arrived here as an ambassador in Scutari. He brought a message from Emperor Alexei III, in which he offered to provide them, if the pilgrims needed it, with everything they needed. Despite the fact that Choniates gives the most derogatory characterization of this extravagant emperor, nevertheless, the basileus had information about the situation among the crusaders and tried to play on the fact that they were not going to campaign against Christians, but against infidels, in the name of saving Jerusalem. But the arguments did not work, especially since the tenacious Venetian Doge did not know his business.

Basileus received the answer that the crusaders did not need the services of the usurper and demanded to vacate the throne for the real heir, Isaac's son, Alexei.

After which the aliens decided to demonstrate the “real” emperor to the capital, the Doge and the Marquis Boniface of Montferrat were on the same ship, and Alexei was with them. They approached the very sea walls of the city, but, according to Villehardouin, out of fear, no one supported the new emperor. However, this surprised all the crusaders, who thought that their thoughts were noble, and they were restoring the rights of the “real” emperor. They could hardly understand that both Isaac and his brother, now the ruler, Alexei III Angel, from the point of view of usurpation, were worth each other.

Preparations for war began, the crusader army was divided into seven detachments.

Count Baudouin of Flanders led the vanguard, having horsemen and a large number of archers and crossbowmen. The second detachment was led by his brother Henri, Mathieu de Valincourt and Baudouin de Beauvoir. The third was commanded by the Count de Saint-Paul, Pierre of Amiens, and his nephew Eustache de Cantelet. The fourth detachment was led by Count Louis of Blois and Chartres. The fifth was commanded by Mathieu de Montmorency, Geoffroy de Villehardouin, Ogier de Saint-Chéron, Manassier de Lisle, etc. In the sixth were the Burgundians Ed de Chanlitte Champagne, Guillaume, his brother, Richard de Dampierre and Ed, etc. The rearguard or seventh detachment was under the beginning of the Marquis Boniface of Montferrat.

With all the knightly bragging, the knights were not confident that they could cope with the defenders, and the Venetians believed that the fleet could only be properly positioned in the Golden Horn Bay, protected from sea storms. The plan was to break into the Golden Horn and be able to attack the city both from the bay and from the north and northwest, in the area of Blachernae.

But first it was necessary to enter the Golden Horn Bay, the path to which was blocked by a chain. It was stretched out from Galata: it was firmly attached to the tower in Galata. And the second end, controlled, was in the tower of Centinaria, actually in Constantinople, next to which there was the gate of Eugene or Marmaroport (“Marble Gate”), since it was lined with marble.

It was located on the shore in the Sea Walls system, in the area of the Vosporion (Prosphorion) harbor, one of two harbors along the southern shore of the Golden Horn. Now, instead of two harbors, there are ferry berths, to the east just behind the Galata Bridge. But if the modern Galata Bridge is located just to the west of these harbors, then the Tower of Centinaria was located to the east, and the chain was stretched right at the very entrance to the bay, covering the Acropolis of the capital from the sea.

The chain was kept afloat by logs.

Part of the chain. Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

The main knightly forces began loading and moving to the Pera area on July 5, 1203, landing in the area of the modern port of Kabatash. The Huissiers, having little maneuverability, were dragged by the galleys. The entire army was fully armed, the knights were in chain mail and with their visors down. The landing party marched to the sound of trumpets. Some of the knights landed directly into the water, occupying a bridgehead.

The Byzantines were already camped here. They crossed the bridge of St. Callinicus at Blachernae, 7–8 km before Galata. Basileus Alexei III arrived at the landing site of the knights with a large army and retinue, which he built according to all the rules of the Byzantine strategems.

After the Huissiers landed, the squires began to lead out their horses, and the knights lined up in detachments. They immediately launched an attack, but contrary to expectations, the large cavalry army of the basileus fled. The knights pursued them to the bridge of St. Callinicus. Choniates is indignant about this:

Thus, the first threat that the pilgrims who had lost their way were afraid of was overcome: the danger of a collision with a large land army of the Romans had passed.

View of Galata. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

A few days later, when the Latins realized that there would be no land resistance, they launched an attack on the fortifications of Galata, with the goal of breaking through the protective sea chain. The crusaders surrounded the tower, settling in the wealthy Jewish quarter of Galata. Several attempts to take the tower failed:

– wrote Robert de Clary.

The tower was defended by the Angles, Pisans and Genoese. On the morning of July 6, 1203, the defenders of the tower and those arriving from Constantinople made a sortie, bringing down the army of the besiegers, led by Pierre de Brachet or Jean d'Aville. They held back the attack of the besieged and attacked themselves with the support of the troops that arrived in time, so they reached the gates of the tower, which they were able to break into.

At the same time, naval battles took place around the chain at sea. It was impossible to break the chain with any “scissors”; the link was about 20–25 cm in length, 4,5–5 cm in diameter. In addition, it was located on huge logs.

Perhaps, after the chain was taken at Pera, it was either cut or broken out of the wall, allowing the Venetian galleys or dromons to break through, the first being the ship "Eagle", probably equipped with a powerful ram to break the chain. Some of the defenders tried to cross to the city side along logs and chains, and they drowned; others escaped on boats and barges.

This is how the naves looked, however, much later in the 1371th century. Naval battle off Calais. 1480 Chronicle of Jean Froissart XNUMX British Library. London.

A small number of triremes, dromons and naves of the Romans who defended the Golden Horn were either captured or thrown ashore. The bay was completely cleared of small fleet Romeev.

Thus, the Romans’ neglect of naval forces led to a tragic consequence, and thirty years ago the Roman fleet was a formidable force opposing the fleet of the Sicilian Normans. The Venetians received a reliable base for their fleet, but a miracle for the Romans, like in August 626, when a storm in the Golden Horn destroyed the Slavs and Avars attacking the city, did not happen.

The entire left bank of the Golden Horn, about 8 km long, was captured. The bridge of St. Callinicus, already dilapidated by the Byzantines across the Varviss River, which flows into the bay, was cleared from the battle. It was located 3 km west of Constantinople. The next day, July 7, the entire Crusader fleet entered here.

View of the northern shore of the Golden Horn, a boat can be seen in the photo. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

The crusaders began to discuss how to conduct further military operations. A dispute arose between the allies, the Venetians proposed attacking the Sea Walls from the waters of the Golden Horn, and the knights believed that they were more accustomed to fighting on land. We decided to use both possibilities.

The crusaders restored the stone bridge of St. Callinicus, crossed it and, as it were, returned back, approaching the walls of Theodosius, the fortifications of New Rome.

They encamped at the monastery of Cosmas and Damian, and set up camp on a hill just below the walls of Blachernae, at the Girolimna Gate, the new fortifications of the Blachernae Palace, built at the end of the 12th century. The besiegers and the besieged could communicate.

Nearby was the parking lot of the Venetian fleet.

The pilgrim fleet could have been stationed at this location. Opposite the walls of Blachernae. Photo by the author.

The newcomers clearly understood that it was unrealistic to take the seven-kilometer Fedoseyev walls and the 5,6 km long sea walls, and decided to attack precisely in the area of the Blachernae Palace. It was also necessary to speed up the assault because the crusaders had supplies for only a few weeks, and there was no way to replenish them. The knights also believed, as Marshal Champagne writes, that their army was significantly smaller than the army of the Roman Emperor.

The latter constantly carried out forays, so that the crusaders could not even forage. After which they surrounded the camp with a palisade and other fortifications.

The Romans made two powerful forays. As Choniates noted, Theodore Laskarites (1174–1218), in his opinion, showed what the glory of the Roman weapons, and his brother, the stratilate of the East, Constantine, was captured by the knights.

These attacks were very dangerous for the besiegers; they were carried out so often that the pilgrims could neither sleep nor eat properly. The parties also exchanged shots from stone-throwing machines, but, again, as Nikita Choniates believed, these sorties were made only for form; Emperor Alexei III himself was already planning an escape.

And the crusaders were in a hurry to storm. Blow number one was to be delivered against the fortifications of Blachernae, which had neither a ditch nor a rampart. And the Venetians, naturally, planned an assault on the city’s Sea Walls. They chose to storm Fort Petrion.

Weapons for siege

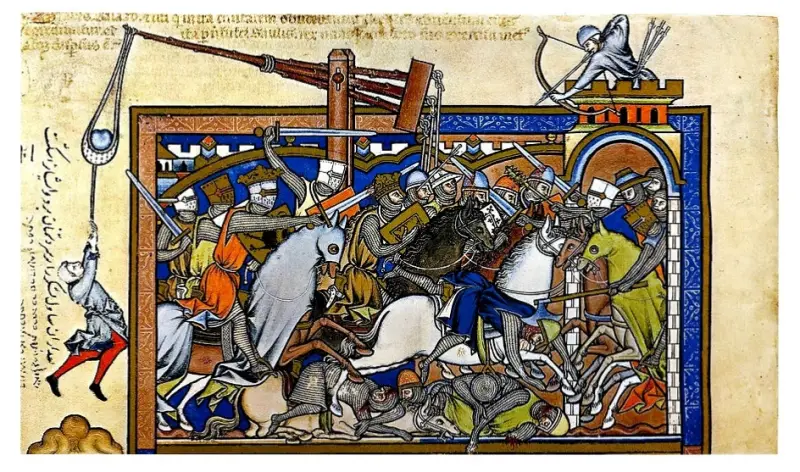

Image of a trebuchet or manganelli. Bible of Cardinal Maciejewski (Louis IX). Morgan Library and Museum. NY. USA.

Sources report that the Crusaders used mangonelli or mangano. This machine looked like a trebuchet. We previously met them during any siege of Constantinople under the name manganika or in Arabic majanika, stone throwers with a fixed counterweight (μαyyανικα). In Tactics of Leo VI, manganiki are clearly distinguished from toxobolista or ballistae.

Ballistas were also used on both sides. The Venetians specially equipped the naves for the assault. A bridge was built on the bow or on the mast, 100 feet (3,2 m) or 200 feet (6,2 m) long,

Perhaps the sides of the ships were also filled with vinegar, which the Latins used against the “Greek fire.”

A winged lion storms the sea walls

On the morning of July 17, 1203, the Venetians lined up in a single formation and moved towards the walls, firing at them from manganicas, crossbows and bows.

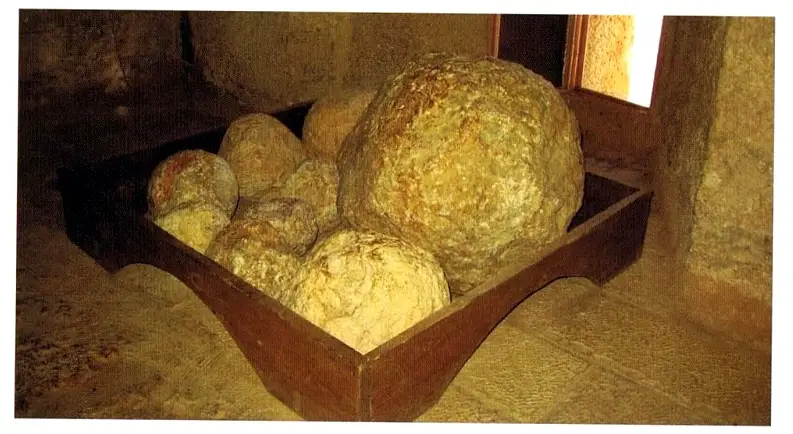

Cannonballs for throwing from manganel or manganica. Ajlun Castle Museum. Jordan.

You need to understand that the sea city walls stood both on the shore itself and at a distance, some 40 m from the sea. From the bridges and stairs of the naves, the Venetians began the battle only with the walls that were directly on the shore; most likely, intense shelling was carried out from most of the naves from bows, crossbows and manganicas. But there were huge naves whose masts were higher than the walls, such as “Cosmos” or “Pilgrim”.

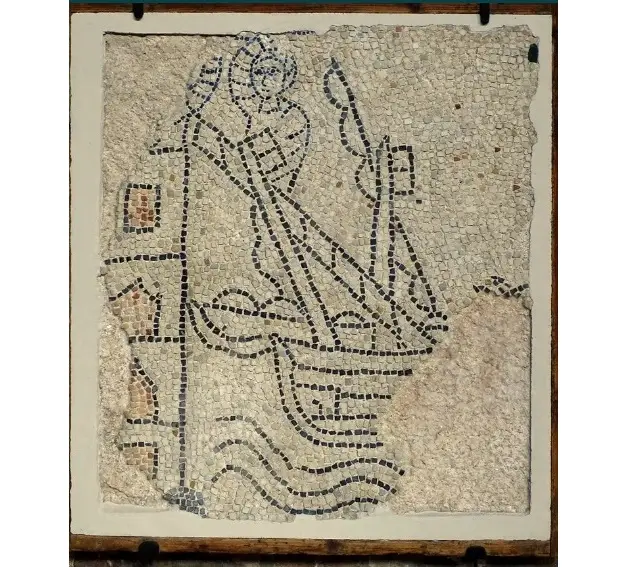

This is how an eyewitness of the Fourth Crusade from Ravenna depicted the ship on the mosaic. Church of San Giovanni Evangelista. Ravenna. Italy. Photo by the author.

The task also consisted of both landing and attacking walls that were not near the water. But here there was a catch, as Villehardouin reports, the galleys could not land. Then the blind doge, dressed in chain mail armor, demanded to be taken to the shore. He himself held in his hands a huge banner of St. Mark, on which a winged lion was depicted. With the help of his squires, he was the first to land on the shore, and the Venetians, seeing this, began to land from Yuissier.

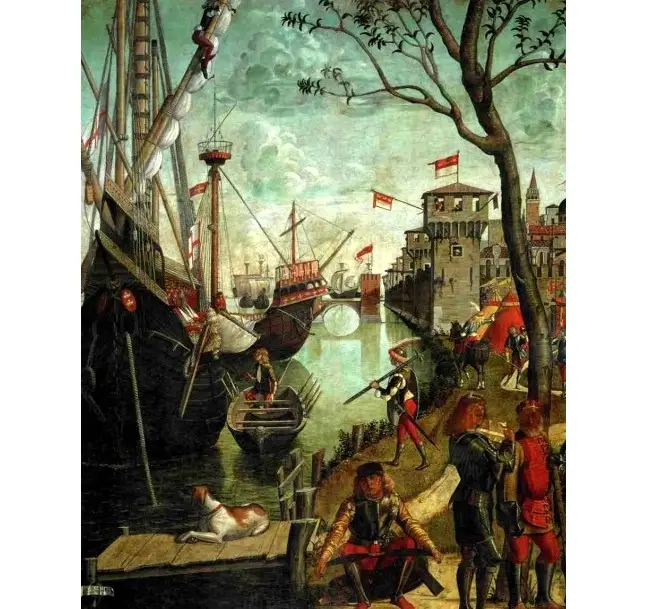

The question remains open: how could they storm the walls directly from ships? A painting by Carpaccio is indicative here, where naves are depicted next to the sea walls: Carpaccio (1465–1525). Arrival of pilgrims in Cologne. Academy Gallery. Venice.

Rams were located on many ships. With the help of one ram, a breach was made in the wall, and the Tsagratoksots (τζάγγρα), as Choniates writes, or crossbowmen, immediately rushed into it. But they were repulsed by the Pisans and the British.

And then, as Marshal Champagne writes, assuring that this was confirmed to him by 40 witnesses, the banner of St. Mark suddenly appeared on the city wall. Such a miracle! But there was no miracle, the Venetians used their shooting advantage, were able to clear the walls of defenders and capture, according to sources, as many as 25 towers in the Petrion area. Immediately the robberies began, they managed to take possession of the horses and send them to Yuissier to the crusaders’ camp.

But earlier a boat had been sent with the message that part of the sea wall of Constantinople had been captured. Forces gathered in the city, and the Venetians realized that they could not cope with them, so they set fire to the Petrion area.

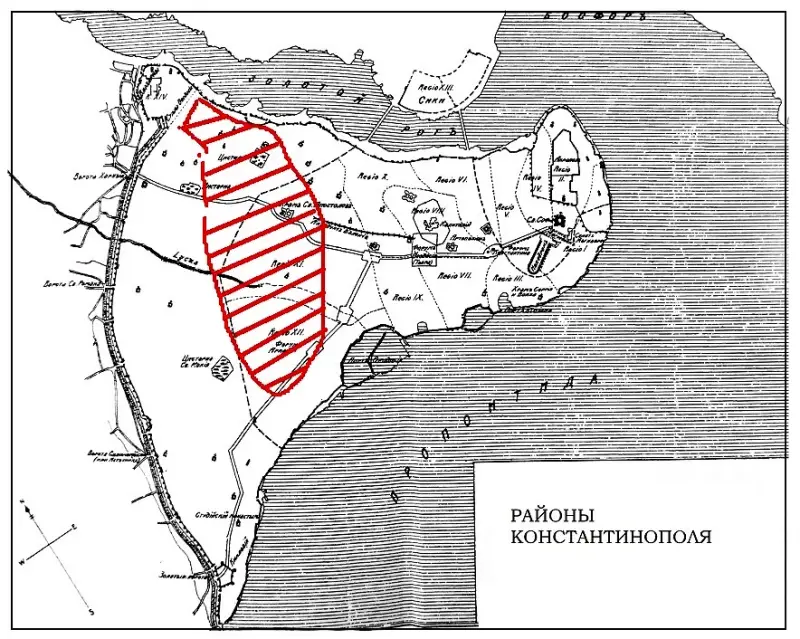

Interestingly, a Russian traveler who happened to be in Constantinople at that time reported that the fire was caused by barrels of resin thrown from ship engines, possibly by manganik. The fire spread to the south of the city, covering almost the entire central part of Constantinople (not to be confused with the city center) and the Blachernae region.

Map of the area of the fire in Constantinople on July 17, 1203, made by the author.

Blacherna attack

While the Venetians were active in the area of Petrion, the knights attempted to take the walls of Blachernae.

Above I wrote that all knighthood was divided into 7 detachments. There were 700 knights in total, the rest were squires, infantry, crossbowmen and archers. Three detachments were supposed to go on the assault, and four remained to protect the camp and guns:

The knights began their assault up just two stairs, and then they were met by the Angles and Danes. Fifteen warriors were able to climb, but the “axe-bearers” repelled the attack, taking two prisoners and sending them to the basileus.

Blachernae fortifications and palace. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

“The last and worst thing is when the husband himself is a woman”

A terrible fire caused by the Venetians caused outrage in the city. The townspeople began to demand that the cowardly and boastful ruler take action. He was forced to gather a mounted army, and the foot army consisted of the entire male population of the capital capable of holding weapons.

The army left the walls of Constantinople and moved towards the Crusader camp. Villehardouin claims that there were 100 thousand Romans or 60 detachments; his younger brother in robbery, Robert de Clari, writes about some 17 detachments.

The women of the city gathered on the walls, watching the battle take place.

The crusaders decided to rely on the fortified camp, as they understood that they had little chance against such an army. Knights, mounted and on foot, lined up in front of the palisade, behind them stood infantry, squires and baggage trains.

In front of the line are archers and crossbowmen. The Count of Flanders lined up his detachment in the correct formation and moved towards the emperor, who with his cavalry troops rushed towards him. At the same time, the emperor quite wisely sent part of the cavalry army to the rear of the crusaders. But the count's advisers suggested that he avoid unnecessary death and retreat under the protection of the palisades.

But the Count de Saint-Paul and his relative Pierre from Amienois decided to attack; they did not respond to all entreaties to stop. And the people of Baudouin of Flanders accused him of dishonor, and he, as a knight, could not help but join the attack of the Count of Saint-Paul. The enemy cavalry was separated by a hill; the first on the hill were the Franks, who stopped awaiting further action in the face of the huge imperial cavalry.

At this time, it is not clear why that part of the army that was supposed to strike from the rear returns to the emperor. And the Venetian army approached the knights, whose doge was ready to die along with the pilgrims, and with the right leadership from the Romans, this dream of his would have been fulfilled on this July day.

But... Basileus Alexei III, whom, obviously, it was not in vain that the imperial treasurer Choniates constantly criticized and scolded him on the pages of his chronicle, is deploying his regiments. And in front of the civilian population of New Rome, he retreats to the country palace of Philopation, located opposite the Selimvri Gate.

Melantia Gate (Porta Melantiados) or Selimvri Gate. Istanbul. Türkiye. Photo by the author.

Some of the knights even pursue the retreating ones. This was salvation for the pilgrims who turned into robbers:

And Basileus of the Romans, to whom

Alexei III was already ready to escape.

He took gold, jewelry, his daughter Irina and fled on July 18 to the city of Debelt (village of Debelt, Burgas region, Bulgaria) 350 km away, then to Adrianople (Edirne) and then to Philippopolis (Plovdiv), leaving the capital to the mercy of fate .

To be continued ...

Information