Wittgenstein's victory at Bar-sur-Aube

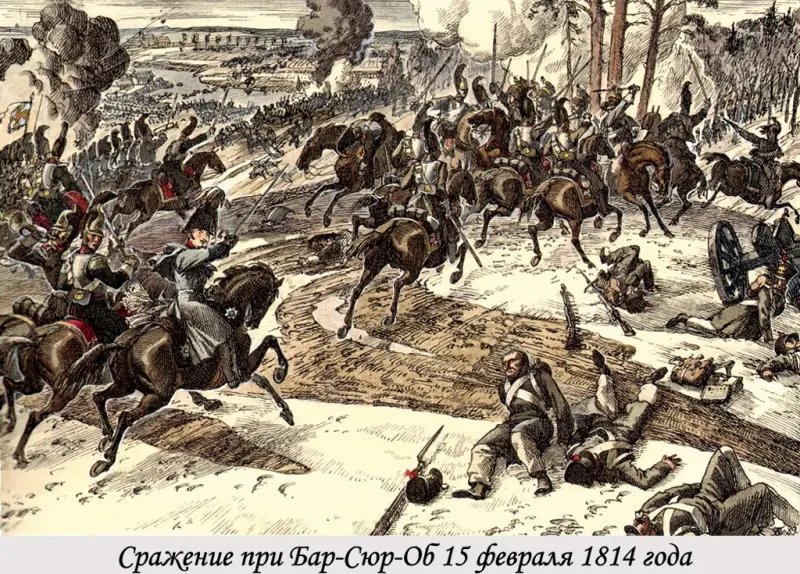

Battle of Bar-sur-Aube. Hood. Oleg Parkhaev

General situation

During a six-day campaign from February 9–14, 1814, Napoleon piecemeal defeated the allied army under the Prussian field marshal Blucher, forcing it to stop the attack on Paris and retreat to Chalons (Napoleon's Six Day War).

Then the French emperor turned his attention to the Main Allied Army under the command of Prince Schwarzenberg. In the battles of Morman and Montreux, he defeated the advanced formations of the Main Allied Army (How Napoleon defeated Schwarzenberg's corps at Morman and Montreux). Schwarzenberg's corps retreated to Troyes.

As a result, the first attempt to attack Paris ended in failure. Bonaparte planned to continue the offensive against the Main Army, cross the Seine and reach the enemy’s communications.

Schwarzenberg continued to act contradictorily and cautiously, fearing the simultaneous advance of Napoleon's troops and the outflanking maneuver of Marshal Augereau from Lyon. The commander-in-chief asked Blucher to come to his aid and join the right flank of the Main Army. The Austrian field marshal planned to fight at Troyes. But on February 22, he suddenly changed his mind and began to withdraw troops from Troyes across the Seine to Brienne, Bar-sur-Aube and Bar-sur-Seine. Schwarzenberg insisted on the need to avoid battle, although he had superior forces.

On February 23, a new envoy, Prince Wenceslaus of Liechtenstein, was poisoned to Napoleon, offering to conclude a truce. However, Napoleon, making sure that his allies feared him, decided to continue the offensive.

Blücher was angry, believing that the Austrians wanted to retreat across the Rhine and make peace with Napoleon. The Prussian commander decided to go to Paris again, to the Marne, in order to divert the enemy’s attention from the Main Army. The Prussian field marshal turned to the Russian emperor and the Prussian king for support. The monarchs who were with the Main Army gave him permission to act independently.

As a result, the allied armies switched tasks.

Now Blucher’s army had to conduct an active offensive, and Schwarzenberg’s Main Army had to solve the auxiliary task, distract and disperse the French troops. Blücher's army included Winzingerode's Russian corps and Bülow's Prussian corps from Bernadotte's Northern Allied Army. And Alexander himself was thinking about leaving the Main Army together with the Russian-Prussian units and joining Blucher.

On February 12 (24), Blucher's army moved through Cezanne and La Ferté-sous-Jouarre towards Paris to meet the marching reinforcements. At this time, Napoleon's army was heading towards Troyes. On February 23, General Gerard overthrew the Austrian rearguard, capturing 4 guns. The French approached Troyes from several directions. However, they did not immediately launch an assault.

Late in the evening, Napoleon ordered batteries to be placed near the city and opened heavy artillery fire. The French then attacked the city three times, but were repulsed by the troops of Archduke Rudolf. On February 24, when all allied troops retreated to the right side of the Seine, the Austrian rearguard cleared Troyes.

Napoleon solemnly entered Troyes. Residents of the city joyfully welcomed him, in contrast to the unfriendly reception three weeks ago. This joy was caused not so much by devotion to the emperor as by the oppression of the Austrians who occupied this city.

In Troyes, Napoleon decided to change the direction of the attack again and turn the army against Blucher. The pursuit of Schwarzenberg could not lead to decisive success, since the Austrian commander-in-chief did not want to engage in battle and could continue to retreat. Napoleon ordered the troops of MacDonald and Oudinot (about 40 thousand people) to continue pursuing the Main Army, and he himself decided with the other half of the army (up to 35 thousand soldiers) to act against Blucher. He was supposed to be supported by the formations of Mortier and Marmont, previously abandoned in the Marne Valley.

Invasion, 1814. Hood. Jean Baptiste Edouard Detaille

Retreat of the Main Army

During the retreat, the troops of the Main Army partially learned some of the sad experience of Napoleon's Great Army, which was retreating from Moscow. The troops retreated at the direction of Schwarzenberg as quickly as if they had lost the campaign. The troops were tired, weakened by many stragglers who were looking for shelter from the cold and food. The morale of the army fell, many believed that the retreat would only be completed beyond the Rhine.

Moreover, they retreated along the same roads along which they moved to Paris. The area was already devastated and could not supply the army with everything necessary. As a result, officers lost confidence in the command, and the soldiers of many formations almost turned into deserters and looters, almost completely losing discipline.

This led to a number of unpleasant incidents.

If at the beginning of the entry of the allied corps and divisions into French territory the local population was rather indifferent to this, then as the armies advanced, these feelings changed dramatically, especially in February-March 1814. A huge army concentrated for battle in one place required food for the soldiers and fodder for the horses (there was no grass in winter). The provinces occupied by the Allied troops were literally devastated by requisitions.

Also, despite the calls of the monarchs and commanders for Christian abstinence and decent treatment of the French, robberies began, destruction of peasant property, arson, rape of women, bullying and murders occurred. This was the sin of soldiers of all contingents of the allied army. But the Prussians, who took revenge on the French, and other Germans were especially different. But for some reason the French press painted only Russian Cossacks as monsters.

The outrages of the Cossacks. Hood. Georg Emanuel Opitz

This forced the French to arm themselves with old hunting rifles, selected weapons from soldiers killed on the battlefields or with scythes, pitchforks and axes. This would not help against regular units. But it was difficult for individual, lagging soldiers and small groups, small units. So, the peasants of the Lower Marne captured 250 Russians and Prussians in four days, who were brutally killed. If the campaign of 1814 had dragged on, and Napoleon had from the very beginning called on the people to resist, giving them some of the weapons from the arsenals, then the Allies would have had a hard time.

Russian soldiers and Cossacks in the house of a Jew. Hood. Georg Emanuel Opitz

On February 25, the three monarchs held a military council in Bar-sur-Aube, to which military leaders and diplomats were invited. It was decided to negotiate at the Congress of Châtillon on behalf of all the Allied powers in order to prevent France from entering into a separate agreement with one of the countries.

Militarily, they decided not to engage in a general battle at Bar-sur-Aube. The main army, in the event of Napoleon's further offensive, was supposed to retreat to Langres and there join the reserves, giving battle to the enemy. Also, Emperor Alexander and King Frederick William demanded that in the event of Napoleon's movement against Blucher's army, the Main Army should immediately launch a counteroffensive.

Alexander, in order to prevent further retreat of the Austrians, said that in this case the Russian regiments would leave the Main Army and unite with Blucher. The Prussian king supported the Russian monarch.

It was also decided to form the Southern Army. It was to include Bianchi's 1st Austrian Corps, the 1st Austrian Reserve Division and the 6th German Corps. This army was supposed to go to Macon, push back Augereau's troops, ensuring communications for the Main Army from the southern flank and covering the Geneva direction.

On February 25–26, Schwarzenberg's troops continued to retreat. On February 26, the King of Prussia and Schwarzenberg received a message that Blücher had crossed the Au River and moved against Marmont, and Napoleon was heading to the Marne, leaving only part of his army against the Main Army. Count Wittgenstein, the commander of the rearguard of the Main Allied Army, reported that French pressure had weakened, which indicated Napoleon's departure.

Wittgenstein suggested immediately launching a counteroffensive. The Prussian king agreed with his opinion and insisted on stopping the retreat and the transition of the advanced corps to offensive actions. On February 27, the corps of Wrede, Wittgenstein and the Crown Prince of Württemberg were to go on the offensive. They were to be reinforced by Russian and Prussian Guards cavalry units. However, they did not have time to arrive at the beginning of the battle.

Campaign in France 1814. Hood. Horace Vernet

Position

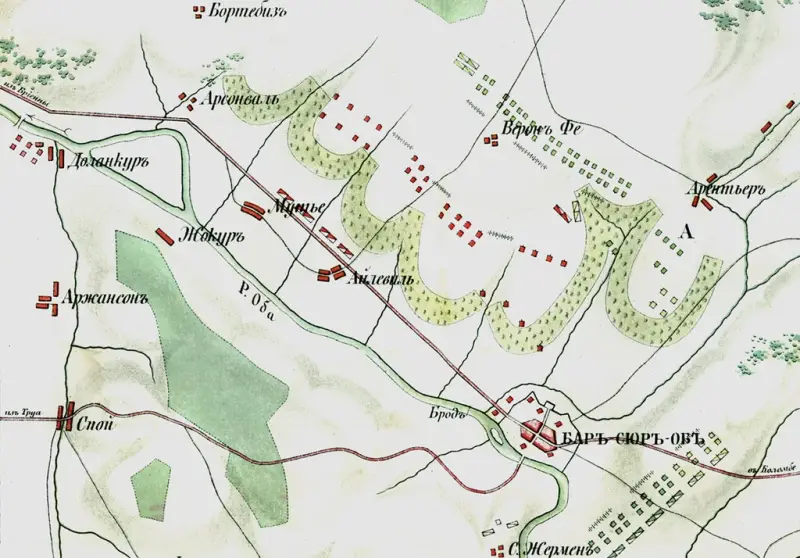

On February 26, 1814, General Gerard, who commanded Oudinot’s vanguard, went to Bar-sur-Aube around noon and occupied it, overthrowing the Austrian division of Gardegg stationed there. General Gerard tried to continue his movement, but was stopped by cross-fire from the batteries of Wrede's corps.

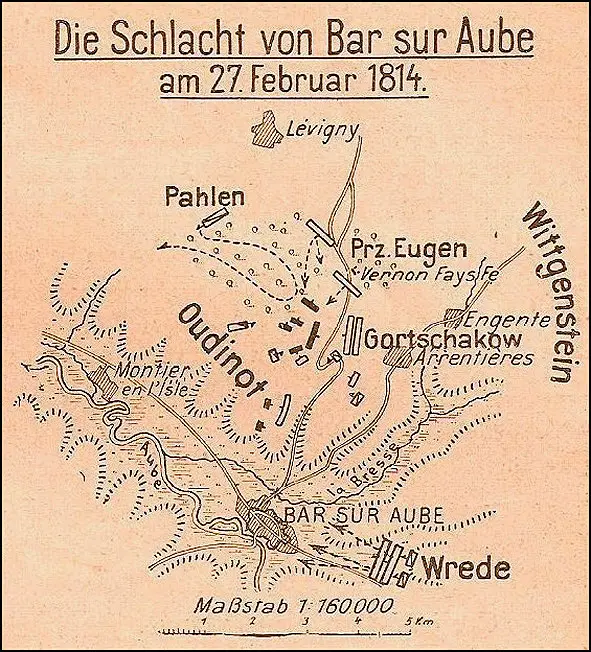

At the beginning of the battle, the disposition of the French troops was as follows: the Pacteau National Guard division was left in Dolancourt; Duhem's division was located in Bar-sur-Aube; two divisions (Leval and Rottemburg) were placed on the plateau north of the city in order to secure the left flank. Also, one division was positioned to communicate these troops with the units that occupied the city. The cavalry was divided into two groups: General Kellerman's corps was located north of the city on the plateau at Spoy, and de Saint-Germain's cavalry at Isleville and Moutiers, behind the infantry formations.

In total, Oudinot had about 30 thousand soldiers. Apparently, Oudinot did not expect a counterattack and planned to continue pursuing the enemy the next day.

Wrede and Wittgenstein were ordered to go on the offensive the next day. The troops greeted this news with joy. Wrende's corps was to attack Bar-sur-Aube. And Wittgenstein’s corps was to support Wrede’s attack and strike to the right of the city, near Isleville.

At night, the Bavarians conducted reconnaissance in force. The 8th Bavarian Infantry Regiment broke into Bar-sur-Aube, captured the outpost and tried to build a road to the center of the settlement, but, encountering superior enemy forces, retreated. The French were able to cut off the advanced units, but they made their way to their own, losing 7 officers and 200 soldiers killed, wounded and prisoners. The regiment commander, Major Massenhusen, also died. However, the Bavarians held the captured suburb.

In the morning, on the plain in front of the city, Vrede formed his troops in two lines. The vanguard was located in front, the Bavarians on the left flank, and Frimont's Austrian division on the right. The flanks were supported by Cossacks with part of the regular cavalry. In addition, the Bavarians occupied the Chaumont suburb. A frontal attack did not promise decisive success, so they decided to bypass the enemy at Leviny.

Wrede's 5th Corps (20 thousand people) was supposed to carry out a demonstrative attack while the rest of the troops bypassed the enemy positions. The bypass was entrusted to Wittgenstein's 6th Corps (16 thousand people). He was supposed to advance in the general direction of Arsonval, capture the bridge at Dolancourt, cutting off the enemy's escape route. Part of Wrede's troops was stationed at Saint-Germain, observing the enemy at Spey.

Battle of Bar-sur-Aube

Battle

At about 10 o'clock in the morning, the Bavarian riflemen started a firefight in the suburbs. At the same time, Wittgenstein's corps, intended to bypass the left flank of the French position, divided into three columns, moved forward.

The first column consisted mainly of cavalry: Grodno, Sumy, Olviopol Hussars, Chuguevsky Uhlan and Ilovaisky, Rebrikov and Vlasov Cossack regiments, 3rd Infantry Division. It was headed by Lieutenant General Count Peter Palen. The column was supposed to move through Arentières and Levigny to Arsonval with the goal of capturing the bridge at Dolancourt.

The second column was composed of elements of the 4th Infantry Division. It was headed by Prince Eugene of Württemberg. She also advanced on Arsonval, to the Dolancourt bridge. The column of the Prince of Württemberg performed the task of maintaining communication between the right and left columns.

The third column consisted of the 5th and 14th infantry divisions, the Pskov cuirassier and Lubny hussar regiments. The column was commanded by Lieutenant General, Prince Andrei Gorchakov II. It was supposed to support the actions of the first columns.

In addition, Major General Yegor Vlastov with two Jaeger regiments was supposed to take positions near the Arentiere River, covering the movements of the remaining troops.

However, Wittgenstein's corps was late with its outflanking maneuver. The French could not be taken by surprise. Oudinot, having discovered the movement of enemy columns, immediately formed troops into battle formations, occupied the forest near Leviny and closed the road from Bar-sur-Aube to Isleville and Arsonval.

The Jaeger regiments, which were part of Palen's column, began a battle with the enemy in the forest near Leviny. The column of the Prince of Württemberg started a battle at Vernopf and, having overthrown the enemy with strong artillery fire, captured the manor. At the same time, Vlastov’s rangers entered the battle. The French General Montfort crossed the ravine with the 101st and 105th line regiments of Leval's division and overthrew the rangers. The Prussian king, who was here with his sons, restored order in the regiments and sent the Russian rangers to a counterattack.

Fearing that the enemy would be able to divide the Allied corps, Wittgenstein ordered Prince Gorchakov not to move behind the second column, but to attack the enemy’s right wing. Wittgenstein personally led the Pskov Cuirassier Regiment to attack, to support the rangers. But rough terrain and vineyards hindered the effective use of cavalry in this area. During the attack, Wittgenstein was injured. Against the French, 4 guns were advanced; they were able to keep the enemy with a shotgun fire. And the regimental rangers of Vlastov, with a new counterattack, overthrew the enemy over the ravine.

At this time, Gorchakov’s column approached. However, before she formed battle formations and went on the offensive, the French cavalry went on the attack. The French managed to transfer Kellerman's cavalry corps from Spoy. The French cavalry overthrew the Pskov cuirassier and Lubny hussar regiments. The French infantry also went on the offensive. There was a threat of separation of the Wittgenstein and Wrede corps and an enemy breakthrough to the rear of the Allied forces.

F. Kamp. Battle of February 15 (27) at Bar-sur-Aube

Therefore, Wittgenstein decided to abandon the outflanking maneuver altogether and ordered the Württemberg and then Palen columns to return. While the troops were returning, the French were held back by the fire of Russian batteries, advantageously placed by generals Levenstern and Kostenetsky.

General Ismert with one of the dragoon brigades of Kellerman's corps tried to capture the guns, but the Russian batteries, allowing the enemy to come within 100 steps, opened fire. With the help of grapeshot, Russian artillerymen repelled several French cavalry attacks. The French lost more than 400 people.

Leval's French division with the attached Chasse brigade continued to advance. It was supported by Rotemburg's division and Saint-Germain's cavalry. At this decisive moment, the Kaluga Infantry Regiment launched a flank attack on the enemy. He was followed by the Mogilev, Perm and other regiments of Prince Gorchakov, supported by artillery fire.

At the same time (at about 4 o'clock in the afternoon) Schwarzenberg ordered Wrede to more actively attack the right wing of the French at Bar-sur-Aube, and sent a detachment of five infantry battalions and five cavalry regiments of Austrian and Bavarian troops to reinforce Wittgenstein. The troops of Gorchakov and Württemberg attacked in unison. Count Palen again received orders to move towards the Dolancourt Bridge.

Oudinot, noticing the strengthening of the enemy and his general offensive, ordered the troops to leave their positions and retreat. At this time, the Bavarians attacked Bar-sur-Aube. Wrede sent 5 battalions to storm the city and sent a detachment of 4 battalions under General Gertling to the right to bypass the enemy.

General Duhem prepared the city well for defense. He blocked all the streets with barricades, and placed batteries at the heights behind the city. Colonel Theobald with the 10th Bavarian line regiment burst into the city, but then things stalled. French riflemen occupied houses and the streets were blocked. We had to storm every house. The French fought hard. Only when it became clear that the main forces had withdrawn and, fearing encirclement, Duhem withdrew the division from the city. The main part of the division retreated along the road to Spoy, several battalions - in the direction of Isleville.

It was not possible to cut off the enemy troops. Palen's cavalry with several guns occupied the Arsonval heights only in the evening, when the main enemy forces were already across the river. Oudinot took out all the artillery. Palen was able to disrupt only the French rearguard with artillery fire.

M. Trenzensky. Austrian light division in the battle of February 15 (27) at Bar-sur-Aube

Results

In the battle of Bar-sur-Aube, French troops lost more than 3 thousand people (2,6 thousand killed and wounded, about 500 prisoners). The Allies lost 1,9 thousand people (according to other sources - 2,4 thousand people). The main losses fell on Russian troops, the Bavarians and Austrians lost 650 people.

Schwarzenberg was shell-shocked. Count Wittgenstein was wounded in the battle. He handed over command to Raevsky (the corps was transferred to Lambert). Wittgenstein's departure was less due to his injury than to disagreement with Schwarzenberg's actions and Wrede's honors. The Bavarian corps did not gain much glory in this battle, but Wrede was awarded the Order of George, 2nd class, and promoted to field marshal. The Prussian king, to his credit, testified to Alexander the bravery of the Russian troops and the skillful management of them by Wittgenstein.

To develop success Schwarzenberg failed or did not want. He feared the emergence of the main forces of Napoleon. Justified by fatigue of troops who had to move in war-ravaged areas. With the appearance of Napoleon would have to depart reinforced marches. Therefore, for the enemy sent only cavalry, supported by small infantry detachments with guns.

On February 16 (28), Oudinot united in Vandeuvres with MacDonald's troops, increasing the number of the French group to 35 thousand soldiers. On the same day, parts of MacDonald's corps entered into battle with formations of Giulai's corps.

At La Ferte-sur-Aube the French lost 750 men killed, wounded and captured. Allied forces lost about 600 people.

Macdonald was forced to withdraw his troops beyond the Seine, leaving Troyes.

On March 5, the Allied forces once again occupied Troyes, but here Prince Schwarzenberg stopped his advance, following the instructions of the Austrian cabinet not to move far beyond the Seine.

The main battles with the French took place to the northwest across the Marne River - between Napoleon and Blucher's army.

Portrait of Count Pyotr Christianovich Wittgenstein. Rice. 1813–1815 author unknown

Information