The beginning of the activities of Xanthippus the Lacedaemonian in Carthage during the First Punic War

prehistory

In 264 (hereinafter all dates except those specified BC) the Roman army under the command of the consul Appius Claudius landed on the territory of the island of Sicily. Thus began the First Punic War. The Romans quickly took control of the city of Messana, knocking out the Carthaginians and Syracusans, and the next year for the second time (the first siege, carried out in 264, ended in failure) they besieged Syracuse and forced the tyrant Hiero II, who ruled there, to conclude a military alliance.

According to the ancient historian Flavius Eutropius, more than fifty (according to Diodorus Siculus - sixty-seven) Sicilian settlements came under the protection of the Romans. By 262, Carthage had lost control of most of its holdings on the island, including the major naval base of Acraganthus, leaving the military initiative on land entirely in the hands of the enemy.

First Punic War

Despite these failures, Carthage still retained supremacy at sea, which could even offset the complete loss of Sicily. The Punic fleet, under the overall command of the commander Hamilcar, regularly carried out raids on the coast controlled by Rome, and many Sicilian cities switched back to the side of the Carthaginians. Trade was also paralyzed. The cities of Caere, Naples, Ostia, Tarentum, Syracuse and others were under threat of ruin.

At the same time, the Romans could not carry out such naval operations; the African coast remained untouched. Realizing that without a powerful fleet the war could not be won, in 260 they began creating ships and training sailors. In this endeavor, Rome was actively assisted by the Italians, who were more advanced and experienced in maritime affairs. In a fairly short period of two months, more than a hundred ships were built.

However, the first combat experience of the Romans at sea was not very successful: in the harbor of the city of Lipara (on one of the Aeolian Islands), the squadron commanded by the consul Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina was blocked by Carthaginian ships under the leadership of Boodes. Roman sailors fled to the shore in panic, their ships were captured by the enemy, and Scipio was captured.

But in the same year 260, the Roman fleet, now led by the consul Gaius Duilius, managed to inflict a heavy defeat on the Punic fleet under the command of Hannibal Giscon at the Battle of Cape Mila. Now Rome could provide naval support to its ground forces in combat operations, as well as threaten the overseas possessions of the Carthaginians.

Subsequently, the Romans captured several cities in Sicily and the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, which were under the control of the Punics, and also inflicted several more defeats on the Carthaginians at sea. Thus, in 258, large forces of the Punic fleet were blocked in the harbor of one of the Sardinian cities and defeated, and their commander, the aforementioned Hannibal, was killed by his own subordinates.

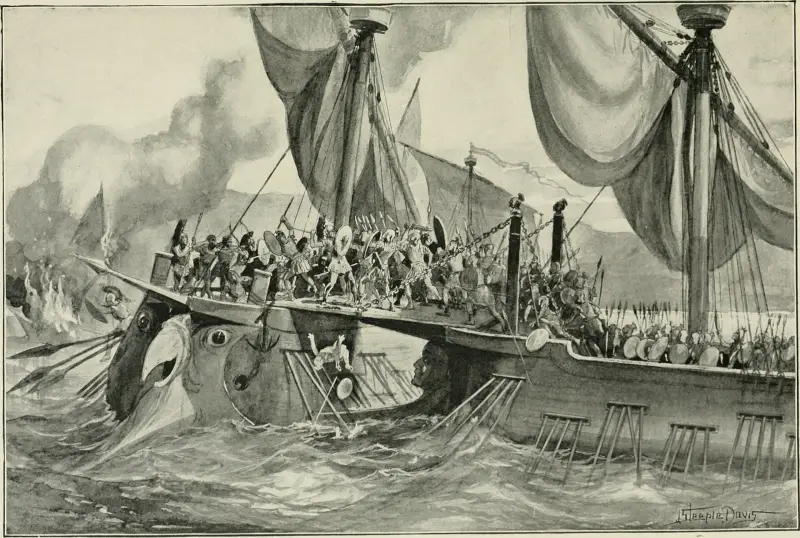

Battle of Milah. Artist: J. S. Davis

Inspired by victories, in 257 the Senate decides to end the war by landing troops in Africa, and thus threaten not only the enemy’s possessions in Sicily, but also his capital, Carthage.

British historian A. Goldsworthy believes that the purpose of the expedition was not to take control of new territories for annexation to Rome, but to put pressure on the Punes in order to force them to accept the most unfavorable peace possible. At the same time, when planning the operation, the Romans hardly intended to capture Carthage itself, because in order to occupy such a large and well-fortified city, they would have to undertake a long and difficult siege.

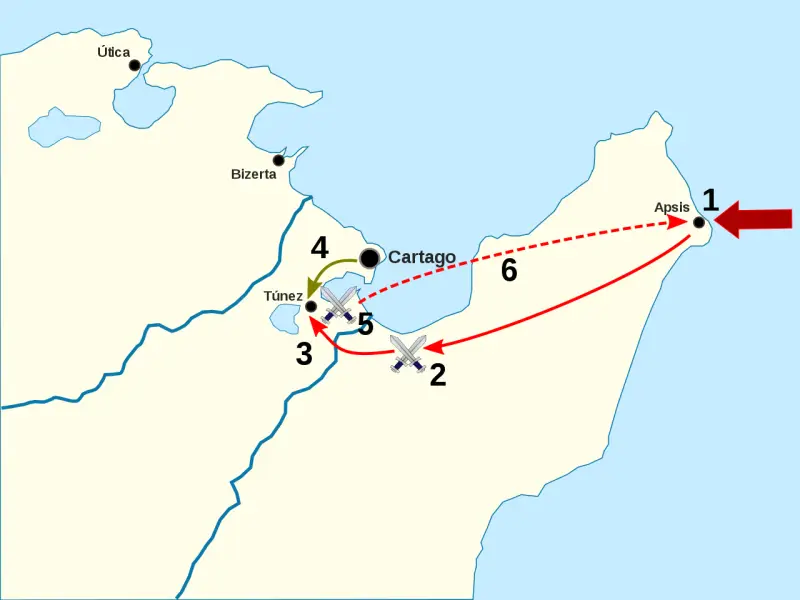

Expedition of Regulus and Vulson to North Africa

In the summer of 256, the Roman fleet under the command of the consuls Lucius Manlius Vulso and Marcus Atilius Regulus won a decisive victory over the Carthaginian fleet in the great battle of Cape Ecnomus (in Sicily). Thus, the Romans opened their way to the shores of Africa. Carthage understood the danger of the current situation and even wanted to start negotiations, but Rome was not yet going to make peace, apparently hoping to put the enemy in a more difficult situation.

The Punes made active preparations for defense and concentrated most of the army and navy near Carthage (city), thinking that the enemy would land there, but these expectations were not realized.

Regulus and Vulson, having prepared food supplies for the expedition, headed to Africa. The ships in their vanguard landed at Cape Hermes (now Cape Et-Tib), waited there for the others and began moving along the coast of the country until they reached the city of Aspida (also known as Klupeya). There the Romans landed on the shore and began a siege.

The news of these enemy actions took the Punes by surprise, because they did not expect the Romans to land in this place and had almost no troops there. For this reason, no active actions were taken to relieve the blockade of Klupeya, and the city soon fell. After the victory, Regulus and Vulso sent messengers to Rome with news of what had happened and a request for instructions on what to do next.

Carthage still kept an army near the capital, and therefore, when the Roman army left its camp and began to devastate enemy territory, no resistance was encountered. According to the ancient Greek historian Polybius, the Romans destroyed many luxurious dwellings, captured many heads of livestock and more than twenty thousand prisoners. Soon, messengers arrived from Rome with an order: one of the consuls to return to Italy along with part of the army, and the other to remain in Africa with the rest.

As a result, Vulson left the theater of operations, taking with him many prisoners (Eutropius writes about 27 thousand), and Regulus remained on Punic soil, having with him 15 thousand infantry, 500 horsemen (according to Goldsworthy, such a small number of cavalry in the expeditionary army , may have been due to the difficulties of transporting horses by sea) and 40 ships (according to Polybius).

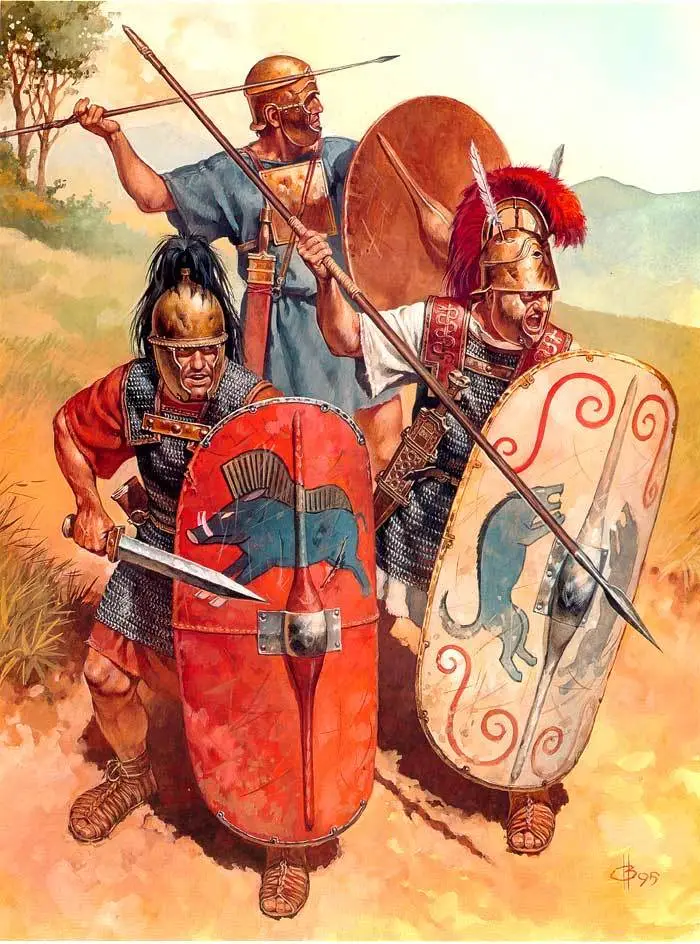

Roman warriors

Soviet antiquarian K. A. Revyako identifies two reasons for the division of the Roman army: firstly, the dissatisfaction of the soldiers with the fact that they were torn away from their own farms for too long, and they fell into disrepair. Secondly, it is the inability of the Roman command to provide such a large army with food.

However, historian E. A. Rodionov notes that problems with army supplies in Africa are not reflected in the primary sources, while nothing prevented the Romans from establishing regular supplies from Sicily, and in general the position of the troops of Regulus and Vulson was very favorable due to plunder local population.

Meanwhile, new military leaders were chosen in Carthage to command the army in the fight against Rome. They turned out to be Hasdrubal, Bostar, and also Hamilcar, who arrived from Sicily along with five hundred horsemen and five thousand infantry. They decided to take more active action and try to stop the Romans from ravaging the country and capturing settlements.

After some time, Regulus' troops approached the city of Adis and besieged it, then the Carthaginians came forward to meet them, hoping to help the besieged. They took a position on a hill near the city and entered into battle with the enemy there, but were defeated (Flavius Eutropius gives, most likely, inflated data about the supposedly 18 thousand killed, 5 thousand prisoners and 18 elephants captured by the Romans).

After this, Adis fell and the Romans marched towards Thunet (near Carthage), which was also taken. In addition, according to Appian of Alexandria, the Romans occupied about two hundred cities (Eutropius writes that after the Battle of Adis, Regulus “took under his protection” 74 cities).

Now the Punes were actually defeated not only at sea, but also on land. The situation was further complicated by the outbreak of the Numidian uprising, as well as food shortages in Carthage and, as a consequence, famine caused by the constant influx of refugees from war-torn territories.

Polybius reports that Marcus Regulus, understanding the plight of the enemy and wanting to end the war this year (since a new consul will be elected next year, and the glory of the winner of Carthage will most likely go to him), proposed peace negotiations.

The Punes agreed (it is worth noting that, according to Diodorus Siculus and Flavius Eutropius, the Carthaginians were the initiators of the negotiations) and sent their envoys led by Hanno to the Romans, but the conditions put forward by the consul turned out to be so harsh and humiliating that peace was never reached. was concluded.

There is almost no information about Regulus’s further plans, but most likely he did not plan to conduct any active offensive operations, intending to wait until the situation in Carthage deteriorated even further, and then try again to make peace.

This ended the 256 campaign in Africa, but a new army was actively gathering in Carthage. Due to the presence of a large amount of precious metals, the Punic government recruited many Greek mercenaries into its ranks. One of them was a Spartan named Xanthippus.

Xanthippus before arriving in Carthage

Almost no specific information has been preserved about the life of this historical figure before he took part in the First Punic War. Nevertheless, based on the meager information available in primary sources, one can try to approximately reconstruct his biography.

Almost all sources known to us directly indicate that Xanthippus was a Spartan. Only Polybius uses a different formulation, calling him “a man of Laconian upbringing,” but if we take into account the fact that only Spartiates (free citizens of Sparta) could receive such an upbringing, we can come to the conclusion that Polybius was simply trying to emphasize the discipline and courage of this military leader.

However, the fact that Xanthippus belonged to the Spartans does not give us complete information about his origin. The fact is that in the third century Lacedaemon was experiencing a crisis (which began in the fifth century), expressed in the property and legal stratification of society, which led to internal instability and numerous political conflicts.

According to the ancient Greek historian Plutarch, it got to the point that at some point there were only about 700 Spartiates, and only 100 of them had land (they were called Gomean). The rest belonged to the categories of hypomeions and mofaks - persons who did not receive land and were therefore deprived of basic civil rights.

By the third century, the hypomeions were already actively engaged in mercenary work, participating in hostilities in different parts of the Hellenistic world.

Xanthippus spent his childhood and youth directly in Sparta (which is associated with the process of his acquiring a “Laconic upbringing”), but Polybius describes him as a man “excellently experienced in military affairs” and calls him “a most experienced man in the art of war,” which means that , that, quite likely, it was the hypomeion.

Based on this, Ukrainian researcher A.I. Kozak suggests that the Spartan fought in many armed conflicts of his time. This is also indicated by Diodorus Siculus, who wrote that Xanthippus had “the natural intelligence and practical experience of a strategist,” and the Roman military theorist Flavius Vegetius Renatus described the Spartan as an experienced and good tactician, from which it can be concluded that he had the opportunity to command very large military contingents.

According to Kozak, Xanthippus could well have taken part in the wars of King Pyrrhus of Epirus (and taken into account their experience when carrying out reforms in the Carthaginian army, but more on that later) or in the Chremonides War (267–261), after which he was in Egypt and became the trierarch of the fleet of the ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, in Halicarnassus, and after a stay with the Punes he returned back and “played a decisive role in the Third Syrian War.”

However, the Russian antiquarian A. A. Abakumov notes that Xanthippus is a mercenary, Xanthippus is a trierarch, and Xanthippus is a participant in the Syrian War (in addition, he was appointed governor of the provinces beyond the Euphrates River by Ptolemy III Euergetes) are not mentioned in the primary sources as one and the same Human. Attempts to “unite” them all into one person do not seem, in his opinion, very justified.

King Pyrrhus of Epirus

However, there is another concept put forward in the 19th century AD. e. German scientist I. G. Droysen in the first volume of his fundamental work “History Hellenism." According to it, only the mercenary and the governor were one person. Supporters of this theory consider the Trierarch of Halicarnassus to be a local native.

Another German, H. Hauben, on the contrary, identifies the trierarch and the governor as one person.

Another question surrounding Xanthippus is how he acquired his knowledge of the art of war. It is known that in Sparta children were taught to read and write, but, as Plutarch wrote, “only to the extent that it was impossible to do without it.” That is, only the necessary minimum of knowledge was given, and “other types of education were subjected to xenelasia.”

Based on this information, we can conclude that in Lacedaemon written culture was considered an unnecessary excess and even a dangerous element, although Flavius Renatus still mentions some works of Lacedaemonian military theorists, but if Xanthippus read them, most likely he still was a practitioner who mastered the military craft empirically.

To summarize, it should be said that by the time of his arrival in Carthage, Xanthippus had rich combat experience and had extensive knowledge in the field of military affairs, which he acquired by taking part in various armed conflicts of the first half of the third century.

Military reform of Xanthippus

According to Polybius, the Spartan commander arrived in Carthage directly from Greece. The historian reports that the Punes sent their recruiter to Hellas, and he brought back a large number of mercenaries, among whom was “a certain Lacedaemonian Xanthippus.”

Once in Carthage, he listened carefully to the stories about the defeat suffered by the Punic army and, having analyzed the information received, came to the conclusion that the cause of the failures was the inexperience of the commanders and, apparently, the imperfection of the tactics they had chosen.

First, Xanthippus expressed his thoughts to his brothers arms, and over time, rumors about a Spartan criticizing the actions of the Carthaginians spread throughout the city, eventually reaching the highest military command. Its members, who were then in a very difficult situation and did not really understand how to get out of it, invited the Lacedaemonian to their place and listened to him.

On the whole, they liked Xanthippus’s inventions, and since he also proposed his own plan of action, the Punic “leaders” appointed him commander-in-chief of the entire army.

However, Appian of Alexandria describes the circumstances of the appearance of the Lacedaemonian in Carthage differently. According to him, the Punes asked Sparta to send them a military leader to lead their army in the fight against Rome, and the Spartans sent Xanthippus.

This information is generally confirmed in their works by Renatus, Eutropius and other Roman historians. That is, in their opinion, Xanthippus received such a high post not during his stay in Carthage, but according to a preconceived plan.

According to the fair remark of A. Kozak, it is not possible to establish which version is more true to reality, because ancient authors used different sources when writing their works. However, according to the researcher, it is worth believing that Xanthippus was appointed commander-in-chief thanks to a political “maneuver” undertaken by someone from the highest echelons of Carthaginian power.

Xanthippus began his activities by taking all the soldiers outside the city walls and beginning to conduct military exercises. For the first time in several years, the Punic army acquired the proper level of combat training.

In addition, the Spartan taught the Carthaginians the competent use of cavalry and elephantery on the battlefield. If previously the Punes occupied positions on the hills, which did not allow the effective use of these types of troops, then thanks to the reforms of Xanthippus, from now on the fighting had to be conducted on the plains. This, looking ahead, became a decisive factor in the victory over the Roman troops under the command of Marcus Regulus in the battle of Tuneta (on the Bagrad River) that took place some time later, which led to their expulsion from Africa.

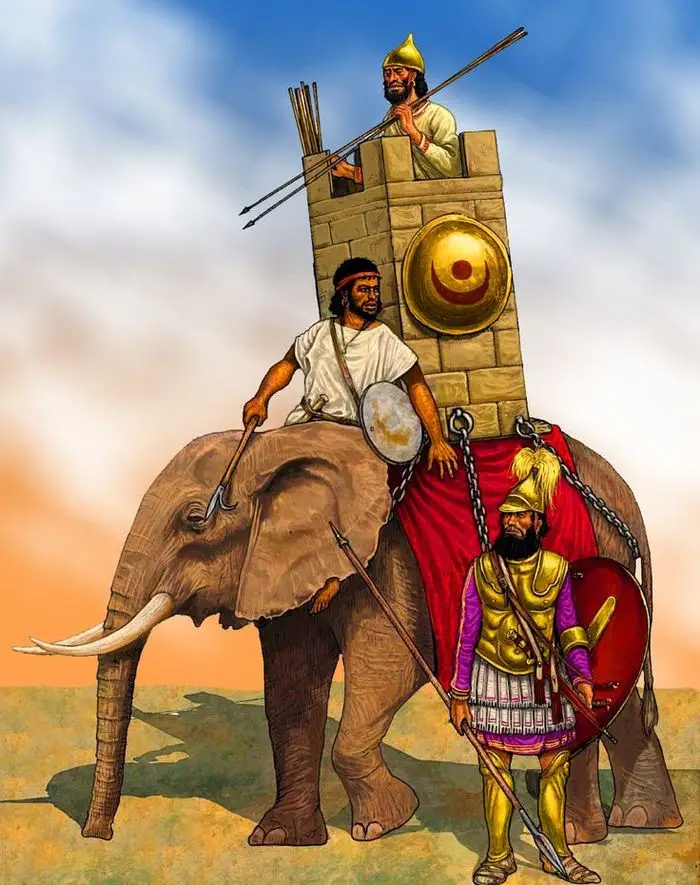

Soldiers of the army of Carthage

The actions of the Spartan were extremely positively assessed by the Punes. Polybius wrote:

A. Kozak suggests that Xanthippus learned to use elephantheria (and not all Hellenic commanders were trained in this) while taking part in the campaigns of Pyrrhus of Epirus. As you know, the king of the Molossians quite actively and successfully used elephants in battles, including against the Romans. Moreover, the Lacedaemonian most likely personally fought in these battles - for the reasons described above, he was unlikely to be familiar with the now lost memoirs of Pyrrhus, which contained a lot of information on military theory. According to A. Abakumov, Xanthippus learned to use elephantery while serving in the army of the Ptolemies or Seleucids, because they also had quite a lot of war elephants.

Some researchers question Xanthippus's contribution to the development of the Carthaginian army and the defeat of Regulus.

Thus, K. Revyako believed that “the defeat of the Romans in Africa is explained by the unpreparedness of the Roman army and navy for such complex military operations, as well as the mediocrity of the Roman high command.” He only partially recognized the role of the Spartans in the Battle of Tuneta.

The German military historian Hans Delbrück, in the first volume of his work “The History of Military Art within the Framework of Political History,” adhered to a similar point of view. In his opinion, the scale of Xanthippus’s activities in Carthage was significantly exaggerated and embellished by Polybius (largely based on the work of the ancient Greek historian Philinus, who sympathized with Carthage), similar to his story that the Romans built their fleet on the basis of a Punian penther washed ashore.

A.V. Guryev, in an article devoted to the reform of Xanthippus, compared the tactics used by the Carthaginians at Tuneta with the tactics they used in their previous wars and battles. In 311, during the fight against the Syracusan tyrant Agathocles (312–305), the Battle of Himera took place. In it, the Punes took up a position on a hill and, skillfully using slingers and heavy infantry, repelled the attacks of the Syracusans. In this case, cavalry was used only at the final stage of the battle.

In the Battle of Tuneta, which took place a year later within the same war, the Carthaginians were already the attacking side, but they used cavalry and chariots only to start a clash, but it ended in defeat. After another unsuccessful battle with Agathocles, this time in 307 in Numidia, the cavalry successfully acted as a rearguard, covering the Punic retreat to the camp, and even managed to push the enemy back. At the second battle of Tuneta (306), the Carthaginians again took up a position on the hill and repelled the Syracusan advance.

But in the war with Pyrrhus of Epirus (278–276), the Punes first “met” war elephants. The Carthaginians included a new branch of troops in their army, but did not use it very actively and skillfully, which can be seen in the clashes of the early stage of the First Punic War.

In the Battle of Akragant (262), elephants were in the second line of troops and were practically not used in battle, and we have no information at all about the actions of the Punic cavalry. In the battle of Adis, where, as mentioned above, a position was also occupied on a hill, the infantry acted almost exclusively, and the elephants and horsemen were in the rear.

Carthaginian war elephant

Based on this, A. Guryev comes to the logical conclusion that before the reforms of Xanthippus, elephantery was used by the Carthaginians mainly to exert a psychological influence on the enemy, and cavalry played a supporting role.

In general, the Punes fought, almost always on the defensive, and attacked the enemy only when they had numerical superiority and confidence in victory. But as a result of Xanthippus's transformations, their tactics changed significantly.

To be continued ...

Primary Sources:

1. Polybius. General history.

2. Appian of Alexandria. Roman history.

3. Diodorus Siculus. Historical library.

4. Flavius Eutropius. Breviary from the foundation of the city.

References:

1. Rodinov E. Punic Wars. St. Petersburg, 2005.

2. Revyako K. A. Punic Wars. Minsk, 1988.

3. Delbrück H. History of military art within the framework of political history T. 1, St. Petersburg, 2005.

4. Goldsworthy A. The fall of Carthage. The Punic Wars 265–146. L., 2000.

5. Guryev A.V. Military reform of Xanthippus // Para bellum. 2001. No. 12.

6. Kozak A. I. Ἄνδρα τῆϛ Λακωνικῆϛ ἀγωγῆϛ: on the question of the social origin of Xanthippus the Lacedaemonian // Laurea I. Ancient World and the Middle Ages. Kharkov, 2015.

7. Kozak A.I. Military-political transformations of Xanthippus the Lacedaemonian in Carthage (256–255 BC) // Punic Wars: history of the great confrontation. St. Petersburg, 2017.

8. Abakumov A. A. Elephants and the Spartan: Xanthippus from Amycles at the Battle of Tuneta (255 BC) // Humanitarian and legal studies. Stavropol, 2020.

Information