Napoleon's Six Day War

The Imperial Guard salutes Napoleon at Champaubert (fragment). G. Chartier

prehistory

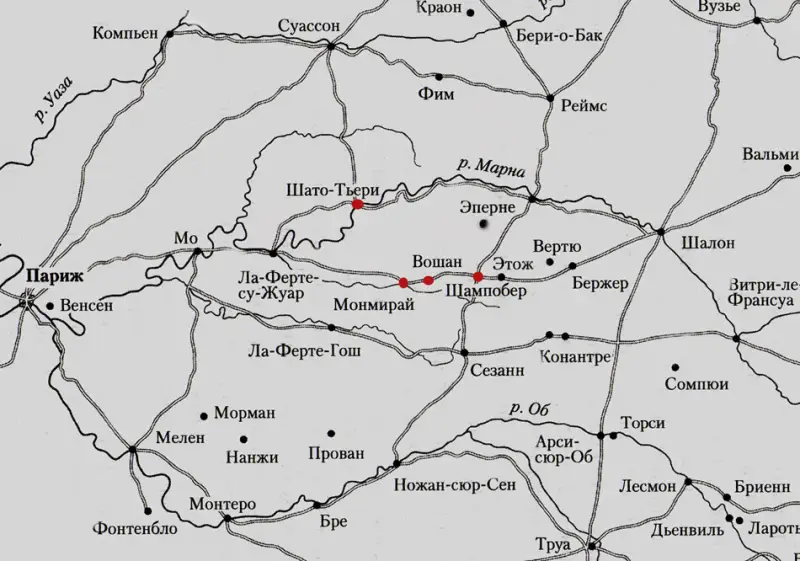

After success at La Rotière (The hot battle of La Rotière) the allies decided to move on Paris, with the two armies going in different directions. The main army under the command of the Austrian Field Marshal Schwarzenberg was supposed to advance along the Seine Valley, having the main forces of the enemy in front of it. The Silesian army of the Prussian Field Marshal Blucher moved to Paris north through the Marne River valley, having in front of him the small corps of the French marshals MacDonald and Marmont.

Schwarzenberg, preparing to attack Troyes, resorted to scientific maneuvers and conducted reconnaissance, wrote a disposition, and ordered the collection of assault ladders and fascines. Due to the caution and slowness of Schwarzenberg (the Viennese court did not want the complete defeat of Napoleonic France), the French army calmly recuperated in Troyes until January 25 (February 6), 1814. The French received reinforcements and then moved to Nogent. Napoleon left a 40-strong barrier under the command of Marshals Victor and Oudinot against Schwarzenberg. He was supposed to guard the river line. Seine.

M. O. Mikeshin. Battle of Montmiral. 1857

Meanwhile, Blücher made a number of mistakes. He developed a vigorous pursuit of Macdonald's weak corps in order to cut it off from Bonaparte's main forces. Blucher's army drove MacDonald away, but its corps were scattered over a wide area. The corps were one or two days' marches from each other and could not quickly help their neighbor.

At the same time, Blucher did not have a strong cavalry; it then served as military reconnaissance, and the Prussian commander did not know about the movement of the French army. A gap formed between the Allied Main Army, which was marking time at Troyes, and the Silesian Army, which did not allow Blücher to receive reinforcements and help from Schwarzenberg in a timely manner.

The main headquarters of Blucher's army was located in Berges near Vertue. Here the Prussian commander awaited the approach of two corps: the Prussian General Kleist and the Russian 10th Infantry Corps, General Kaptsevich. They were supposed to arrive by February 10, but due to muddy roads they were late.

Naturally, Napoleon makes the logical decision to attack the flank of Blucher’s army, which was scattered along the Marne and, moreover, came closer than 100 km to Paris. Arriving in Nogent, the emperor carefully considered his plan of action for 2-3 days. When the French diplomat and politician Hugues-Bernard Marais entered Bonaparte to present him with dispatches to Chatillon for signature, he found him lying on the floor and carefully studying a map studded with pins: “Oh, it’s you. I’m now busy with completely different things: I’m mentally smashing Blucher.”.

Having joined Marmont's corps on the morning of February 10, Napoleon crossed the Saint-Gond swamps on the march. The emperor ordered to collect all the horses in the area and attract the local population to help. The French soldiers moved knee-deep in mud, lost their shoes, and were exhausted from fatigue, but encouraged by the presence of Napoleon himself, who shared with them all the difficulties of the transition, they approached Blucher’s troops in the Marne Valley.

The French army reached the town of Champaubert, suddenly finding itself on the internal communications of Blucher's army. Thus began a series of victories by Napoleon over the Silesian armies, which among historians became known as the Six-Day War.

Battle of Champaubert

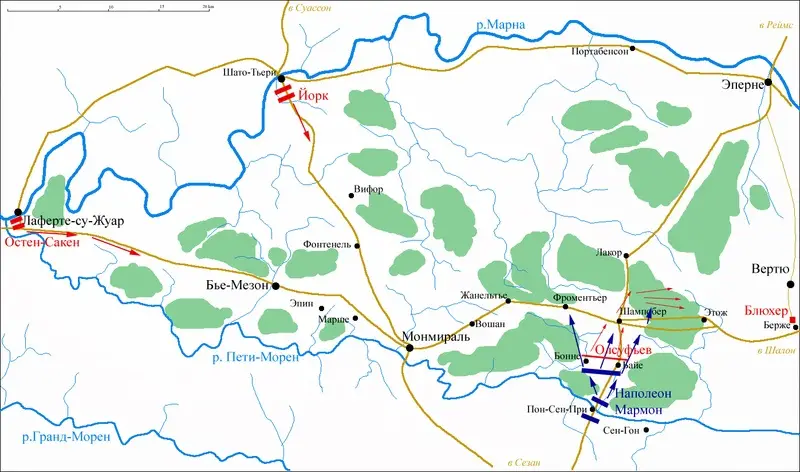

The advancing French army consisted of 2 divisions of the Old Guard of Marshal Mortier (8 thousand soldiers), 2 divisions of the Young Guard of Marshal Ney (6 thousand people), and the corps of Marshal Marmont (6 thousand people). The cavalry consisted of the guards cavalry of General Grouchy (6 thousand people), the 1st Cavalry Division (2 thousand sabers) and the heavy cavalry division of General Defrance (2 thousand), a total of 10 thousand people. In total, Napoleon had about 30 thousand soldiers (20 thousand infantry and 10 thousand cavalry) and 120 guns at his disposal.

Near the town of Champaubert there was the Russian 9th Infantry Corps under Lieutenant General Olsufiev. The corps was seriously weakened by previous battles and numbered only 3 soldiers with 700 guns. Olsufiev did not have cavalry and therefore could not set up long-range patrols. Only on the morning of January 24 (February 29) did he become aware of the unexpected appearance of significant enemy forces from the south, from Cezanne.

On the morning of February 10, Marshal Marmont's corps attacked the Russian vanguard. The first attacks of the French were repulsed, but soon Olsufiev was forced to draw all available forces into battle. The corps took a position between the villages of Bayeux and Banne, where until noon the Russians managed to repel scattered attacks by Napoleon’s approaching formations.

The evening before the Battle of Champaubert. Nicolas Toussaint Charlet

The evening before the Battle of Champaubert. Nicolas Toussaint CharletAround noon, the French emperor himself arrived on the battlefield with his guards. The attacks resumed with redoubled force, and soon the village of Bayeux was already in French hands. At the military council, the Russian generals decided to retreat to Vertu, to join Blucher. However, an order came from the field marshal, according to which Olsufiev had to defend Champaubert to the last, as a point connecting Blucher’s main apartment (headquarters) with other parts of his army.

Blucher reported: “Your fears are in vain; Napoleon cannot be here; in the detachment operating against you, there are no more than 2 people, led by some brave partisan, and therefore I strictly confirm to hold Champaubert as a place connecting my army in Vertu with Saquin’s corps in Montmiral.”

By order of Blucher, other corps of the Silesian Army - the Prussian General York and the Russian General Osten-Sacken - were to come to the rescue of Olsufiev.

Battle of Champaubert

The persistent resistance of the Russians forced Bonaparte to assume that the enemy had large reserves. The Emperor, exaggerating the number of Russians, decided to begin outflanking maneuvers in order to cut off likely escape routes. The French cavalry bypassed the flanks of the small Russian corps, and in the evening surrounded it, cutting off the escape route to Etozh.

The soldiers of Major General Konstantin Poltoratsky, resisting in Champaubert, having repelled several cavalry attacks, fought hand-to-hand, fighting off with bayonets, as they ran out of ammunition. Poltoratsky began a retreat to the forest, forming troops in a square. But the forest was already occupied by French riflemen. In response to the offer to surrender, the Russians refused. Enemy artillery shot the square, and the cavalry completed the rout. Poltoratsky was wounded and captured. He was released during the capture of Paris.

In one of the skirmishes, Zakhar Dmitrievich Olsufiev himself was wounded and captured. Napoleon suggested that Olsufiev make a request to Emperor Alexander I to exchange him for the French general Vandam, who was captured in 1813, but Olsufiev rejected this proposal. He was released from captivity a few weeks after the Allied forces captured Paris.

Command of the remnants of the troops was taken by the commander of the 15th division, Major General Pyotr Kornilov. Under the cover of darkness and under the cover of the forest, the general was able to save the remnants of the corps. About 1 people carried out their wounded and went to Blucher's location. We managed to save all the banners and 700 guns.

During the battle, Russian losses amounted to 2 thousand killed and captured, and more than 270 wounded were brought to their own. 9 out of 24 guns were lost in the battle. The remnants of the 9th Corps were annexed to the 10th Corps of General Kaptsevich.

Battle of Champaubert February 10, 1814. Marmont's cuirassiers and dragoons attack the Russians, right side. Charles Langlois

Battle of Champaubert February 10, 1814. Marmont's cuirassiers and dragoons attack the Russians, left. Charles Langlois

In the evening, during dinner, the following conversation took place between Napoleon and the captured generals Olsufiev and Poltoratsky:

– 3 people with 690 guns.

- Nonsense! Can't be! There were at least 18 people in your corps.

“The Russian officer will not talk nonsense: my words are the real truth.” However, you can ask other prisoners about this.

– If this is true, then, to be honest, only Russians know how to fight so brutally. I would bet there were at least 18 of you.”

Further, Bonaparte, paying tribute to the fortitude of the Russian soldiers, said:

Later, addressing Marshals Berthier, Ney and Marmont, who were present at the dinner, Napoleon said: “If tomorrow I am as happy as I am today, then in 15 days I will drive the enemy back to the Rhine, and from the Rhine to the Vistula is just one step.”. And added: “And I will make peace with France maintaining its natural borders.”.

Portrait of Zakhar Dmitrievich Olsufiev, workshop of George Dow

Portrait of Konstantin Markovich Poltoratsky from the Military Gallery of the Dow workshop

Battle of Montmiral

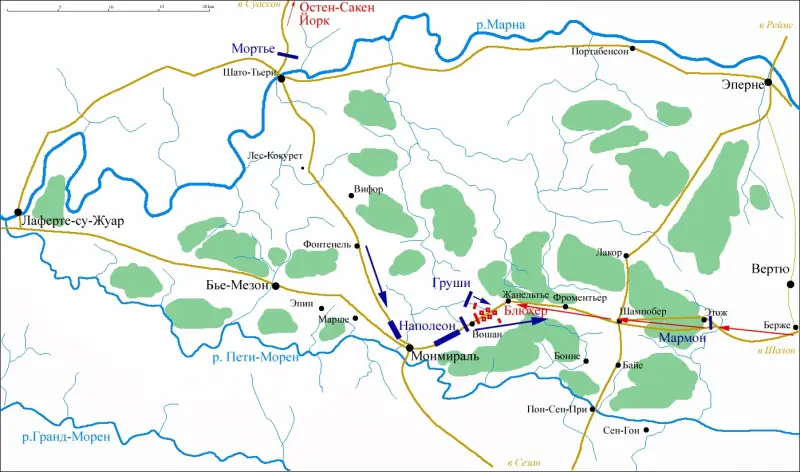

After the defeat of Olsufiev's 9th Russian corps, Napoleon, leaving Marmont's 8-strong corps and Grusha's cavalry to provide cover from Blucher, turned the army to the west and moved the guard to Montmiral, which he arrived at at 10 o'clock in the morning. Under his command were 20 thousand of the most combat-ready guard soldiers.

At this time, at Bieu-Maison, on the road to Montmiral, the vanguard of General Osten-Sacken's corps appeared. Saquin's corps, having advanced far forward to Paris, threw back Marshal MacDonald's corps to the city of Meaux and the day before occupied Laferte-sous-Juar. Now, by order of Blucher, he returned by forced march back to Montmiral to link up with York, and retreat first to Vertue, and then link up with the corps of generals Kleist and Kaptsevich. But it was too late, the French had already wedged themselves between the two wings of the Silesian army.

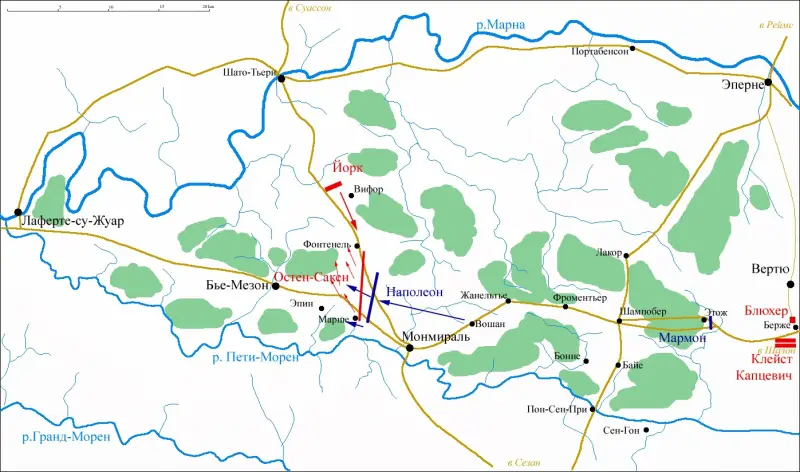

Osten-Sacken's Russian corps consisted of 14 thousand soldiers. Later, during the battle, he was joined by a Prussian brigade from York’s corps - 4 thousand soldiers. Approaching the town, Osten-Sacken lined up his corps in battle formation. The Russian general positioned his troops from the village of Marche near the river. Petit Morin on the right flank, through the center in the area of the road to Montmiral to the village of Fontenelle on the left flank, where the troops of the Prussian corps were supposed to approach.

Battle of Montmiral

Saken decided to take the fight, as he expected that the enemy forces were small in front of him. The forward posts of the Russians and French began a firefight at 9 a.m. on January 30 (February 11), 1814, and soon the battle unfolded along the entire line. York arrived at Sacken with the message that the Prussian infantry did not have time to arrive on the battlefield, and the artillery could not get through the muddy roads and was sent back to Chateau-Thierry. Only one Prussian brigade was able to reach the left flank of Sacken by 3 o'clock in the afternoon, which was forced to reinforce it with Russian batteries.

The village of Marche on the right flank of the Russian corps, defended by General Talyzin, became the scene of the most fierce battle and changed hands several times. The battle continued with varying success until 8 pm. When the Russians once again drove the soldiers of General Ricard's division out of Marchais, the Old Guard division led by General Friant bypassed Marchais and occupied the village of Épin behind Russian lines. The French cut the road for retreat. At the same time, Ricard counterattacked and repulsed Marchais.

Guards dragoons of the French army in the battle of Montmiral. Keith Rocco

Trying to cut off the enemy's right flank, Bonaparte broke through the center of the Russian battle formation. The Russian troops had no choice but to retreat north towards Chateau-Thierry. Part of Saken's body was blocked, but was able to break through. The retreat was covered by the Prussians of York and Vasilchikov's cavalry, which repelled the attack of Nansouty's cavalry. As night fell, the stubborn fighting stopped. By dawn, Osten-Sacken's regiments, moving through the pouring rain in close infantry formation through wooded and swampy terrain in the light of fires, reached Vifor.

The Russian general was able to withdraw most of the corps, artillery and convoy from the battle. In a stubborn battle, the allies lost up to 4–5 thousand people. Napoleon's losses are estimated from 2 thousand to 3 thousand soldiers.

Late in the evening, an envoy returned from Blucher's headquarters with orders to immediately cross the Marne and go to Reims to join the main forces. General York proposed to begin crossing the Marne as quickly as possible, but Saken, fearing for the fate of most of the artillery park and convoys, persuaded him to take a position near the village of Les-Kakuret (Les-Kokuret) in front of Chateau-Thierry to cover the retreat.

Battle of Montmiral in France, February 11, 1814. Lithograph by Louis Stanislas Marine-Lavigne from a painting by Horace Vernet

Battle of Chateau-Thierry

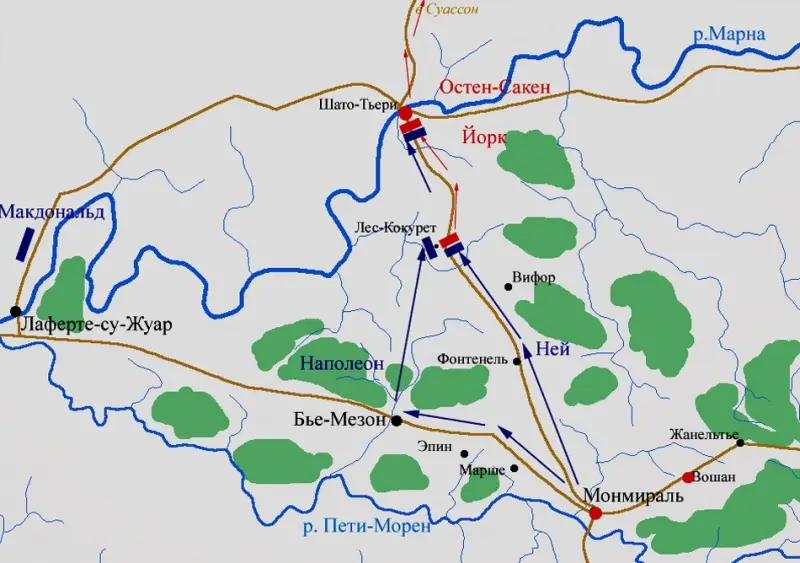

On the morning of January 31 (February 12), 1814, the allies took up a position near the town of Les Kakuret. The Prussian cavalry of General Valen-Yurgas pulled up to York. The Allied forces numbered about 28–30 thousand (18 thousand Prussians and 10–12 thousand Russians).

Napoleon developed the pursuit of the retreating allies. He was approached by 2 horsemen sent by Marshal MacDonald. French troops numbered about 500 thousand people.

Bonaparte sent Marshal Ney along the direct road Montmiral - Chateau-Thierry, and he himself moved towards the allies along the bypass road Bieu-Maison - Chateau-Thierry. Approaching Les Cacourts, the French opened heavy artillery fire. Then Ney, under the cover of artillery, threw infantry and cavalry into the attack. The cavalry managed to defeat the infantry square, and the Allied soldiers fled into the forest, where the horsemen could not pursue them. York gave the order to retreat to Chateau-Thierry, to the crossing point across the Marne.

To cover the retreat to the other side of the Marne, 4 Russian and 3 Prussian battalions were left in front of Chateau-Thierry. The French attacked the rearguard with superior forces and soon drove it back to Chateau-Thierry. The remnants of the Tambov and Kostroma regiments (the day before deployed at Marchais), as the Russian military historian M. Bogdanovich wrote, were bones, and their wounded commander, General Ivan Heidenreich, was captured.

The battle on the streets of the town was still ongoing when the bridge over the Marne was blown up. The Allied soldiers remaining in Chateau-Thierry had no choice but to fold weapon. However, the pursuit of the broken corps of York and Osten-Sacken became impossible.

The Emperor sent an order to Marshal MacDonald, whom York had driven beyond the Marne shortly before the battle, to return to Chateau-Thierry to finish off the remaining Allied troops on the other side of the Marne. However, Macdonald did not receive the order on time, and the corps of York and Saken calmly left to join Blucher.

At Chateau-Thierry, the Russians lost almost 1 people, the Prussians - 500, and the French - only 1 people.

Battle of Chateau-Thierry. Jean-Antoine-Simeon Faure

Battle of Voshan

Blücher, cut off from his army at his headquarters in Berges, was gathering troops. On January 30 (February 11), the corps of Kleist and Kaptsevich (a total of 15–17 thousand soldiers) approached him with a delay. The remnants of Olsufiev’s broken corps also arrived. Blucher was afraid to attack the enemy without strong cavalry and, only having received 1 cavalry regiments as reinforcements on February 13 (2), he decided to attack Marmont’s corps (8 thousand people), left by Napoleon as a barrier.

Marmon did not accept the fight and began to retreat. Then the Prussian field marshal decided to strike in the rear of Napoleon’s army, which, according to his disposition, was to pursue the corps of York and Saken. Blucher did not yet know that these corps, after the battle of Chateau-Thierry, were thrown back beyond the Marne. Blucher's troops numbered 17–20 thousand people.

Having learned about the movement of Blucher's troops, Napoleon in the early morning of February 2 (14) went to the rescue of the retreating Marmont and found him behind Vauchamp. The settlement itself was occupied by the Prussians under the command of General Zieten. From 11 a.m., Ricard's French division attacked Vauchamp twice, but was repulsed each time.

Bonaparte sent Grouchy's cavalry to encircle the village on the left, while Lagrange's division at the same time made a detour to the right. Ziethen's five battalions retreated from the village, subjected to a powerful cavalry attack. Of these, only 500 people survived.

Meanwhile, Leval's division, which had recently arrived from Spain, approached the French. For Blucher, the appearance of Napoleon's main forces came as a surprise. The field marshal ordered a retreat. He formed the infantry in a square; the small Prussian cavalry covered the flanks.

Having emerged along the highway into a narrow passage between the forests, the squares formed infantry columns on both sides of the highway. Artillery moved along the highway, firing back. For several hours, the troops, formed in small squares, took on the artillery fire of General Drouot and repelled the attacks of the French cavalry. By sunset, Blücher's troops reached Champaubert in order.

Grouchy's French cavalry bypassed Champaubert, intercepting the route of further retreat to Etoges. Blucher's regiments made a breakthrough. The French cavalrymen cut down the infantry. The Union infantry, mostly recruits, fought back desperately, cutting their way with bayonets. More than once Blucher himself, generals Kleist, Kaptsevich and others were in danger.

Also, powerful artillery, which paved the way, played a big role in saving the allies. The French Guards artillery was stuck in the mud on the bypass roads, so the cavalry could not hold off Blücher's brave infantry. Two Russian battalions died during the retreat, two Prussian regiments were forced to capitulate. But the rest of the troops broke through, reached the Etoga Forest by nightfall and continued on to the camp in Berge.

At 10 o'clock in the evening, Marshal Marmont sent several battalions of Lagrange's division to outflank Etoges from the left flank. The French were able to deliver a surprise attack on the Russian rearguard. During the battle, a bridge over a swampy ditch collapsed, so the soldiers, cut off from the departing army, were trapped. The commander of the Russian 8th Infantry Division, Major General Alexander Urusov, was wounded and captured with his headquarters. 600 people from his division were also captured, and the French captured 4 guns.

Allied losses amounted, according to various estimates, from 6 thousand to 8 thousand soldiers. According to the inscription on the 52nd wall of the gallery of military glory of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, Kaptsevich’s corps near Voshan lost 2 thousand people. Napoleon's own losses, according to French sources, amounted to about 1 people.

French cuirassiers during the attack. Divisional General Marquis Grouchy with his heavy cavalry brilliantly crushed the enemy and paved the way through the enemy infantry squares. Horace Vernet

Results

Blücher was able to organize defense and overnight accommodation only in Berges, from where he then retreated to Chalons, where on February 5 (17) he linked up with York and Osten-Sacken. The Allies lost a total of 15–18 thousand people (almost a third of the Silesian army), up to 50 guns and a significant part of the supplies. The army was weakened and morally depressed.

Napoleon, in a letter to his brother Joseph, rightly calling the Silesian army the best army of the coalition, wrote: “The enemy’s Silesian army no longer exists, I have completely dispersed it...” He habitually exaggerated, but if he had a few more days, he could have finished off Blucher’s army.

Napoleon planned to pursue Blücher to Chalons and complete the defeat of his army. Then turn against Schwarzenberg's Main Army. However, the offensive of the main Allied forces on Paris, which already threatened the French capital, forced the emperor to abandon this plan.

Schwarzenberg repeated Blucher's mistake, scattering his corps over a long distance, which allowed Napoleon to defeat individual allied units in a number of battles.

The largest of them was the battle of Montreux on February 6 (18). The allies offered Napoleon a truce, which he refused, trying to negotiate more favorable peace terms with the help of weapons. Schwarzenberg withdrew to Troyes, where he linked up with Blücher, and then to the initial offensive position, in the area of Bar-sur-Aube and Bar-sur-Seine.

On February 11 (23), 1814, Napoleon returned to Troyes, which he had abandoned 18 days earlier after the defeat at La Rotière. As a result of the Six Day War, the initiative in the campaign temporarily passed into the hands of the French Emperor. He won this game.

Battle of Montmiral. French cavalry attacks a square of Russian troops. Wojciech Kossak

Information