The invasion of the Crimean-Kazan horde saved Lithuania from complete defeat

Mehmed Giray near Moscow. Facial chronicle vault. 1521

Glinsky's betrayal

The fall of Smolensk greatly strengthened the authority of the Moscow sovereign. Almost immediately, the nearest cities - Mstislavl, Krichev and Dubrovna - swore allegiance to Vasily Ivanovich. Vasily III, inspired by this victory, demanded that his commanders continue offensive actions.

An army under the command of Mikhail Glinsky was moved to Orsha, and detachments of Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov, Dmitry Bulgakov and Ivan Chelyadnin were moved to Borisov, Minsk and Drutsk.

The enemy became aware of the plans of the Russian command. Prince Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky, who during the Russian-Lithuanian War of 1507–1508. went over to the side of Moscow, now decided to return to the hand of the Polish king Sigismund. Glinsky wanted to receive Smolensk as an inheritance, which he helped take (“Command the hail to strike from all sides”), but the Grand Duke of Moscow refused him. The offended prince turned to the Polish king, and he promised him mercy. By preliminary agreement, the Lithuanian army went to the Dnieper, when it was already not far from Orsha, Glinsky fled to him at night.

However, one of his servants notified the Moscow governor, Prince Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov, who captured Mikhail Lvovich and took him to Dorogobuzh, where Tsar Vasily III was located. Glinsky did not deny the betrayal: letters from Sigismund were found in his possession.

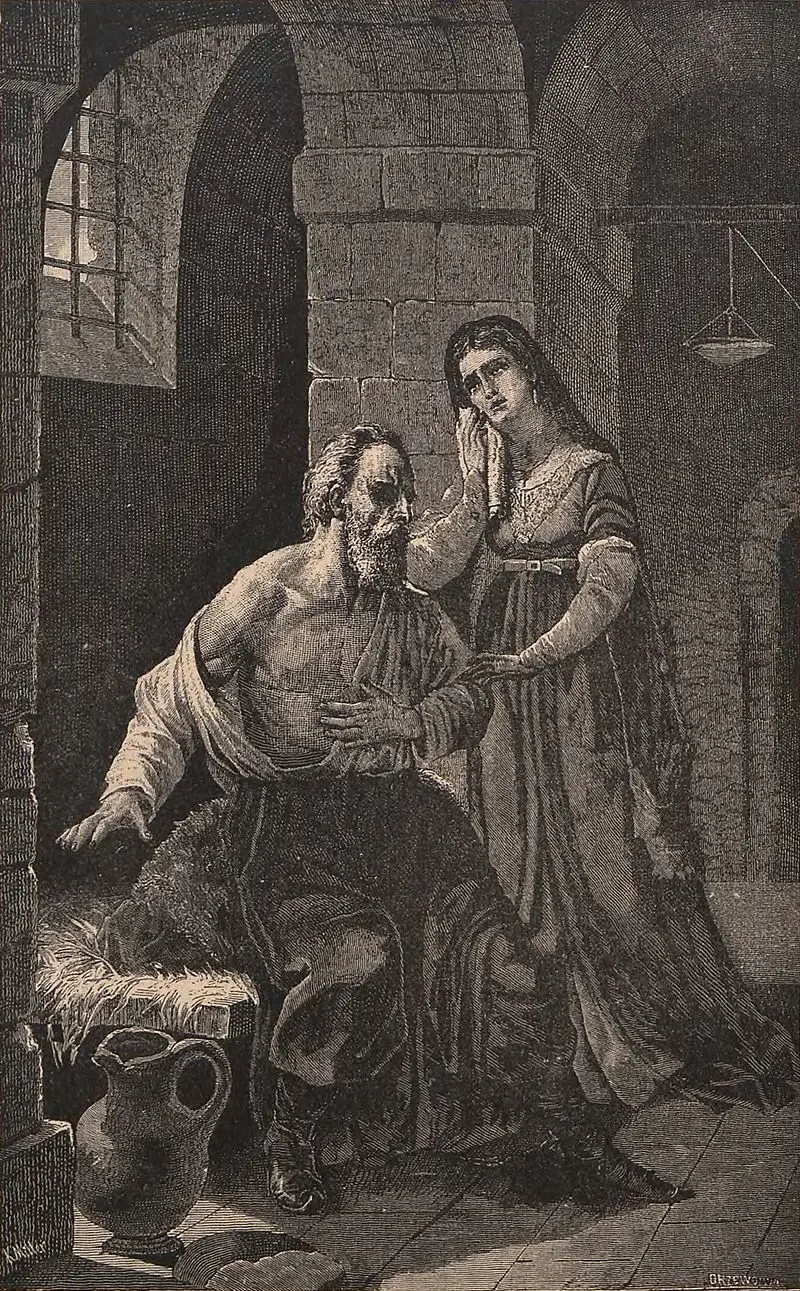

Mikhail Glinsky remained in captivity for a long time. He was baptized into the Orthodox faith. In 1526, Grand Duke Vasily III married Mikhail's niece, Elena Vasilievna. A year later, the Grand Duke’s young wife obtained her uncle’s freedom, but the boyars gave double guarantee, pledging, in the event of Mikhail Lvovich’s escape, to pay a large sum to the treasury.

Glinsky and his wife in prison. Polish lithograph 1901

Number of troops

Thanks to Glinsky's betrayal, the enemy received information about the size, location and routes of movement of the Russian army.

King Sigismund left a 4-strong detachment with him in Borisov and moved the rest of the army towards the forces of Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov. The Polish-Lithuanian army was commanded by the experienced commander, the Great Hetman of Lithuania Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky and the Court Hetman of the Polish Crown, Janusz Swierczowski.

The Lithuanian army was a feudal militia, consisting of “povet banners” - territorial military units. The Polish army was built according to a different principle. The noble militia still played a large role in it, but Polish commanders used mercenary infantry much more widely. The Poles recruited mercenaries in Livonia, Germany and Hungary. A distinctive feature of the mercenaries was the widespread use of firearms weapons. The Polish command relied on the interaction of all types of troops on the battlefield: heavy and light cavalry, infantry and field artillery.

The size of the Polish army is also unknown. According to the information of the 25th-century Polish historian Maciej Stryjkowski, the number of combined Polish-Lithuanian forces was about 26–15 thousand soldiers: 3 thousand Lithuanian Commonwealth, 5 thousand Lithuanian Gospodar nobles, 3 thousand heavy Polish cavalry, 4 thousand heavy Polish infantry. At the same time, XNUMX thousand soldiers were left with the king in Borisov.

According to the Polish historian Z. Zhigulsky, in total there were about 35 thousand people under the command of Hetman Ostrozhsky: 15 thousand Lithuanian Commonwealth, 17 thousand hired Polish cavalry and infantry with good artillery, as well as 3 thousand volunteer cavalry fielded by Polish magnates .

Russian historian A. N. Lobin believes that the Polish-Lithuanian forces were approximately equal to the Russians: 12–16 thousand people. However, the Polish-Lithuanian army was more powerful, consisting of light and heavy cavalry, heavy infantry and artillery.

Polish armor of the 1510s. Polish Army Museum, Warsaw

The number of Russian forces is unknown. Polish-Lithuanian sources call the huge size of the army. King Sigismund in his epistole to Pope Leo X reports about the “Muscovite horde” - 80 thousand people. Obviously this is propaganda. Only part of the Russian army was near Orsha. After the capture of Smolensk, Emperor Vasily Ivanovich himself went to Dorogobuzh, several detachments were sent to devastate the Lithuanian lands. Part of the forces moved south to repel a possible attack by the Crimean Tatars. Therefore, the maximum number of troops of Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov and Ivan Chelyadnin was 35–40 thousand. The minimum was 12 thousand.

Russian historian A.N. Lobin calculated the size of the army near Orsha, based on the mobilization ability of those cities whose people were in the troops. Lobin points out that in the regiments, in addition to the children of the boyars of the Sovereign's court, there were people from 14 cities: Veliky Novgorod, Pskov, Velikiye Luki, Kostroma, Murom, Tver, Borovsk, Volok, Roslavl, Vyazma, Pereyaslavl, Kolomna, Yaroslavl and Starodub. In the army there were: 400–500 Tatars, about 200 children of the boyars of the Sovereign's regiment, about 3 thousand Novgorod and Pskov residents, 3,6 thousand representatives of other cities, in total about 7,2 thousand nobles. With military slaves, the number of troops was 13–15 thousand soldiers.

Taking into account the losses during the offensive, the departures of nobles from service (the wounded and sick had the right to leave), noted in the sources, Lobin believes, the number of soldiers could be about 12 thousand people. In fact, it was the so-called. “light army”, which was sent on a raid across enemy territory. The personnel of the “light army” were specially recruited from all regiments and included young, “spirited” boyar children with a significant number of good horses and with fighting serfs with spare and pack horses.

Armament of the Russian foot warrior of the 1869th century. Reconstruction by F. G. Solntsev based on armor from the collection of the Armory Chamber, XNUMX. Album “Clothes of the Russian State”

Battle

On August 27, 1514, Ostrogsky's troops, having crossed the Berezina, with a surprise attack, shot down two advanced Russian detachments that were stationed on the Bobr and Drovi rivers. Having learned about the approach of enemy troops, the main forces of the Moscow army retreated from the Drutsk fields, crossed to the left bank of the Dnieper and settled between Orsha and Dubrovno, on the Krapivna River.

On the eve of the decisive battle, the troops stood on opposite sides of the Dnieper. The Moscow governors apparently decided to repeat the battle of Vedrosh, which was victorious for Russian weapons. They did not stop the Lithuanians from establishing crossings and crossing the Dnieper. In addition, according to Polish and Russian sources, Hetman Ostrozhsky began negotiations with Russian governors; at this time, Polish-Lithuanian troops crossed the Dnieper.

On the night of September 8, the Lithuanian cavalry crossed the river and covered the crossings for the infantry and field artillery. From the rear, the army of the great Lithuanian hetman Konstantin Ostrozhsky had the Dnieper, and the right flank rested on the swampy river Krapivna.

The hetman built his army in two lines. The first line was the cavalry. The Polish heavy cavalry made up only a quarter of the first line and stood in the center, representing its right half. The second half of the center and the left and right flanks were made up of Lithuanian cavalry. The second line consisted of infantry and field artillery.

The Russian army was built in three lines for a frontal attack. The command placed two large cavalry detachments on the flanks somewhat in the distance; they were supposed to encircle the enemy, break through to his rear, destroy bridges and encircle the Polish-Lithuanian troops.

The success of the Polish-Lithuanian army was facilitated by the inconsistency of the actions of the Russian forces. Mikhail Bulgakov had a local dispute with Chelyadnin. Under the leadership of Bulgakov was the Right Hand regiment, which he led into battle on his own initiative. The regiment attacked the left flank of the Polish-Lithuanian army. The governor hoped to crush the enemy flank and go to the enemy’s rear.

Initially, the Russian attack developed successfully and, if the rest of the Russian forces had entered the battle, a radical turning point could have occurred in the battle. Only a counterattack by the elite cavalry of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - the Hussars (winged hussars), under the command of the court hetman himself, Janusz Swierczowski, stopped the attack of the Russian forces. Bulgakov's troops retreated to their original positions.

After the failure of Prince Bulgakov’s attack, Chelyadnin brought the main forces into the battle. The advanced regiment under the command of Prince Ivan Temka-Rostovsky struck enemy infantry positions. The left-flank detachment under the leadership of Prince Ivan Pronsky launched an attack on the right flank of the Lithuanian Commonwealth of Yuri Radziwill. The Lithuanian cavalry, after stubborn resistance, deliberately fled and led the Russians into an artillery ambush - a bottleneck between a ravine and a spruce forest. A salvo of field artillery became the signal for a general offensive of the Polish-Lithuanian forces.

Now Prince Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov did not support Ivan Chelyadnin. The outcome of the battle was decided by a new blow from the Polish men-at-arms - they hit the main Russian forces. Chelyadnin's regiments fled. Part of the Russian troops was pressed to Krapivna, where the Russians suffered the main losses.

The Polish-Lithuanian army won a convincing victory.

Of the 11 major governors of the Russian army, 6 were captured, including Ivan Chelyadnin, Mikhail Bulgakov, and two more died. The King and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Sigismund I, in his victorious reports and letters to European rulers, said that the 80-strong Russian army had been defeated, the Russians had lost up to 30 people killed and captured. The Master of the Livonian Order also received this message; the Lithuanians wanted to win him over to their side so that Livonia would oppose Moscow.

The death of the left-flank cavalry detachment of the Russian army is beyond doubt. However, it is clear that most of the Russian army, mainly cavalry, most likely simply scattered after the attack by the Polish flying hussars, suffering certain losses. There is no need to talk about the destruction of most of the Russian 12- or 35-strong army. And even more so, one cannot talk about the defeat of the 80-strong Russian army (most of the Russian armed forces of that time). Otherwise, Lithuania would have won the war.

The battle ended with a tactical victory of the Polish-Lithuanian army and the retreat of Moscow forces, but the strategic importance of the battle was insignificant. The Lithuanians were able to recapture several small border fortresses, but Smolensk remained behind the Muscovite state.

Battle of Orsha, painting by an unknown author

Campaign 1515–1516

As a result of the defeat at Orsha, all three cities that came under the rule of Vasily III after the fall of Smolensk (Mstislavl, Krichev and Dubrovna) broke away from Moscow. A conspiracy arose in Smolensk, headed by Bishop Barsanuphius. The conspirators sent a letter to the Polish king with a promise to surrender Smolensk. However, the plans of the bishop and his supporters were destroyed by the decisive actions of the new Smolensk governor, Vasily Vasilyevich Nemoy Shuisky. With the help of the townspeople, he uncovered the conspiracy: the traitors were executed, only the bishop was spared (he was sent into exile).

When Hetman Ostrozhsky approached the city with a 6-strong detachment, the traitors were hanged on the walls in full view of the enemy army. Ostrozhsky made several attacks, but the walls were strong, the garrison and the townspeople, led by Shuisky, fought courageously. In addition, he did not have siege artillery, winter was approaching, and the number of soldiers leaving home increased. Ostrogsky was forced to lift the siege and retreat. The garrison even pursued him and captured part of the convoy.

In 1515–1516 A number of mutual raids were carried out on border areas, but there were no large-scale hostilities. On January 28, 1515, the Pskov governor Andrei Saburov identified himself as a defector and captured and ravaged Roslavl with a surprise attack. Russian detachments went to Mstislavl and Vitebsk. In 1516, Russian troops ravaged the outskirts of Vitebsk.

In the summer of 1515, detachments of Polish mercenaries under the command of J. Sverchovsky raided the Velikiye Luki and Toropets lands. The enemy failed to capture the cities, but the surrounding area was heavily devastated.

Sigismund continued to try to create a broad anti-Russian coalition. In the summer of 1515, a meeting took place in Vienna between the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, Sigismund I and his brother, the Hungarian king Vladislaus. In exchange for the cessation of cooperation between the Holy Roman Empire and the Muscovite Kingdom, Sigismund agreed to renounce claims to Bohemia and Moravia.

In 1516, a small detachment of Lithuanians attacked Gomel; this attack was easily repelled. During these years, Sigismund had no time for a big war with Moscow - the army of one of the Crimean “princes” of Ali-Arslan, despite the allied relations established between the Polish king and Khan Muhammad-Girey, attacked the Lithuanian border regions. The planned campaign against Smolensk was disrupted.

Moscow needed time to recover from the defeat at Orsha. In addition, the Russian government had to solve the Crimean problem. In the Crimean Khanate, after the death of Khan Mengli-Giray, his son Mohammed-Giray came to power, and he was known for his hostility towards Moscow. Moscow’s attention was distracted by the situation in Kazan, where Khan Mohammed-Amin was seriously ill.

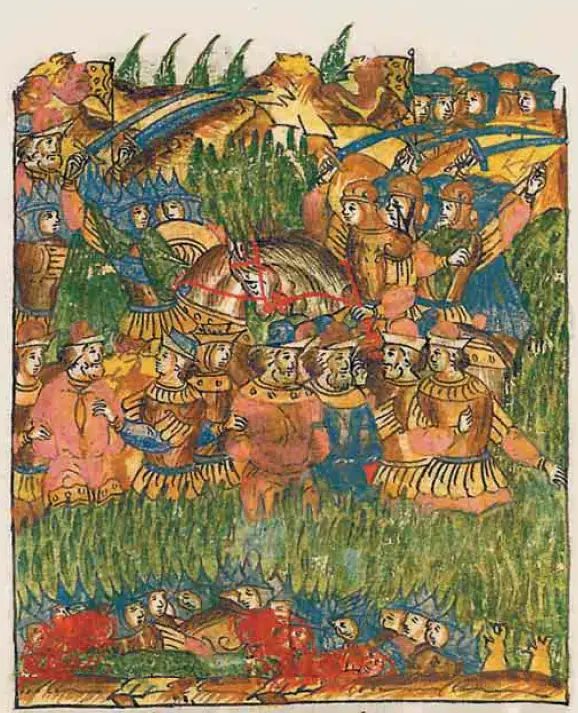

Facial chronicle vault. 1514 "About the Battle of Orsha."

1517 Campaign

In 1517, Sigismund planned a major campaign to the north-west of Rus'. An army under the command of Konstantin Ostrozhsky was concentrated in Polotsk. His blow was supposed to be supported by the Crimean Tatars. They were paid a significant sum by the Lithuanian ambassador Olbracht Gaschtold, who arrived in Bakhchisarai. The Russian state was forced to divert its main forces to fend off the threat from the southern direction, and had to repel the attack of the Polish-Lithuanian army with local forces.

In the summer of 1517, a 20-strong Tatar army attacked the Tula region. The Russian army was ready, and the Tatar “driven” detachments scattered across the Tula land were attacked and completely defeated by the regiments of Vasily Odoevsky and Ivan Vorotynsky. In addition, the retreat routes for the enemy who began to retreat were cut off by “Ukrainian men on foot.” The Tatars suffered significant losses. In November, the Crimean detachments that invaded the Seversk land were defeated.

In September 1517, the Polish king moved an army from Polotsk to Pskov. While sending troops on a campaign, Sigismund simultaneously tried to lull Moscow's vigilance by starting peace negotiations. The Polish-Lithuanian army was headed by Hetman Ostrozhsky; it included Lithuanian regiments (commander - J. Radziwill) and Polish mercenaries (commander - J. Swierchowski).

Very soon it became clear that the attack on Pskov was wrong. On September 20, the enemy reached the small Russian fortress of Opochka and got stuck here. The army was forced to stop for a long time, not daring to leave this Pskov suburb in the rear. The fortress was defended by a small garrison under the command of Vasily Saltykov-Morozov.

The siege of the fortress dragged on, negating the main advantage of the Lithuanian invasion - surprise. On October 6, Polish-Lithuanian troops, after bombing the fortress, moved to storm it. However, the garrison repelled a poorly prepared enemy attack, and the Lithuanians suffered heavy losses. Ostrogsky did not dare to launch a new assault and began to wait for reinforcements and siege guns.

Several Lithuanian detachments that were sent to other Pskov suburbs were defeated. Prince Alexander of Rostov defeated a 4-strong enemy detachment, Ivan Cherny Kolychev destroyed a 2-strong enemy regiment. Ivan Lyatsky defeated two enemy detachments: a 6-strong detachment 5 versts from Ostrozhsky’s main camp and the army of governor Cherkas Khreptov, which was marching to join the hetman to Opochka. The convoy, all the guns, the squeaks, and the enemy commander himself were captured.

Due to the successful actions of Russian forces, Ostrozhsky was forced to lift the siege on October 18 and retreat. The retreat was so hasty that the enemy abandoned all “military arrangements,” including siege artillery.

The failure of Sigismund's offensive strategy became obvious. In fact, the unsuccessful campaign depleted the financial capabilities of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and put an end to attempts to change the course of the war in its favor. Attempts to gain the upper hand on the diplomatic front also failed. Vasily III was firm and refused to return Smolensk.

Portrait of Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky (1460–1530). Russian military and statesman of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Orthodox Ostrohsky family

The last years of the war

In 1518, Moscow was able to allocate significant forces for the war with Lithuania. In June 1518, the Novgorod-Pskov army, led by Vasily Shuisky and his brother Ivan Shuisky, set out from Velikie Luki towards Polotsk. It was the most important stronghold of Lithuania on the northeastern borders of the principality.

Auxiliary strikes were carried out far into the interior of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Mikhail Gorbaty's detachment carried out a raid on Molodechno and the outskirts of Vilna. The regiment of Semyon Kurbsky reached Minsk, Slutsk and Mogilev. The detachments of Andrei Kurbsky and Andrei Gorbaty devastated the outskirts of Vitebsk. Russian cavalry raids caused significant economic and moral damage to the enemy.

The Russian army did not achieve success near Polotsk. At the beginning of the century, the Lithuanians strengthened the city's fortifications, so they withstood the bombardment. The siege was not successful. Supplies were running out, one of the detachments sent for food and fodder was destroyed by the enemy. Shuisky retreated to the Russian border.

In 1519, Russian troops launched a new offensive deep into Lithuania. Detachments of Moscow governors moved to Orsha, Molodechno, Mogilev, Minsk, and reached Vilna. The Polish king could not prevent the Russian raids. He was forced to throw troops against the 40-strong Tatar horde of the son of the Crimean Khan Bogatyr-Saltan, which invaded Galicia, ravaging the Russian, Belz and Lublin voivodeships.

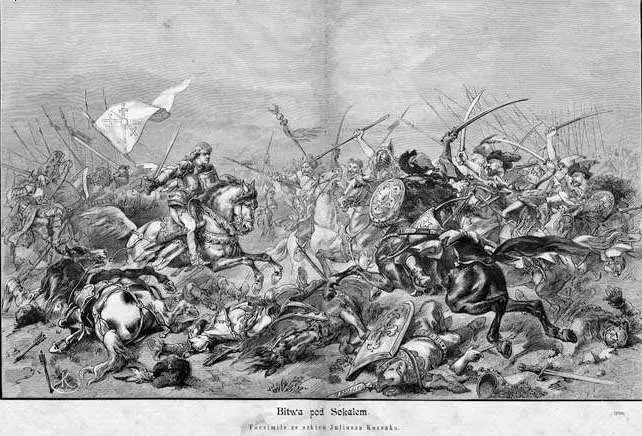

On August 2, 1519, in the Battle of Sokal, the Polish-Lithuanian army under the command of the Grand Hetman Crown Nicholas Firlei and the Grand Hetman of the Lithuanian Prince Konstantin Ostrogsky was defeated. The Polish commanders, not listening to the experienced Ostrozhsky, decided to attack the enemy themselves on the left bank of the Bug, without waiting for the Crimeans to cross. Having crossed the river, the Poles came under fire and attack from light enemy cavalry attacking from the flanks. The terrain was inconvenient for Polish heavy cavalry. The Poles and Lithuanians had to flee.

After this, the Crimean Khan Mehmed Giray broke the alliance with the Polish king and Grand Duke Sigismund (before this, the Crimean Khan dissociated himself from the actions of his subjects), justifying his actions by losses from Cossack raids. To restore peace, the Crimean Khan demanded a new tribute.

Moscow in 1519 limited itself to cavalry raids, which led to significant economic damage and suppressed its will to resist. The Lithuanians did not have large forces in the Russian offensive zone, so they were content with the defense of cities and well-fortified castles. In 1520, attacks by Moscow regiments continued.

Battle of Sokal. Facsimile image of a sketch by Juliusz Kossak

The truce

In 1521, both powers faced significant foreign policy problems. Poland entered into a war with the Livonian Order (war of 1521–1522). Lithuanian Rus' was exhausted by the war. Sigismund resumed negotiations with Moscow and agreed to cede the Smolensk land.

Moscow also needed peace. A coup took place in Kazan, power was seized by Sahib Giray, brother of the Crimean Khan Mehmed Giray. The Crimean Khan gathered a huge army of up to 100 thousand people. In addition to almost the entire Crimean Horde, it included Nogai, Kazan Tatars and a Lithuanian detachment.

In 1521, one of the largest Tatar invasions took place (Crimean tornado. How the Crimean and Kazan hordes destroyed Moscow Russia). The Crimean Horde broke through the Oka border and, due to the governor’s mistakes, defeated the Moscow regiments separately. The Russian army retreated to the cities, the horde ravaged the land.

Meanwhile, the Kazan Horde, under the leadership of Sahib Giray, took Nizhny Novgorod, ravaged the outskirts of Vladimir and moved to join the Crimean army along the Oka to Kolomna. Tatar troops united in Kolomna and began to jointly attack Moscow. The outskirts of the capital were ravaged and burned. The Moscow authorities were forced to admit their dependence on the Crimean Khan, and Vasily agreed to pay him tribute, which was paid to the khans of the Golden Horde.

Then the horde tried to take Ryazan, but the governor Khabar Simsky held the city. The Crimean Khan led the horde away. Tsar Vasily refused to pay tribute. The army had to be kept on the southern and eastern borders in order to prevent new attacks by the Crimean and Kazan detachments.

Therefore, Vasily III agreed to a truce, renouncing part of his claims to Lithuania - demands to give up Polotsk, Kyiv and Vitebsk.

On September 14, 1522, a five-year truce was signed. Lithuania was forced to come to terms with the loss of Smolensk and territory - 23 thousand km2 with a population of 100 thousand people. However, the Lithuanians refused to return the prisoners. Most of the prisoners died in a foreign land. Only Prince Mikhail Golitsa Bulgakov was released in 1551. He spent about 37 years in captivity, outliving almost all of his fellow prisoners.

Ten Years' War 1512–1522 showed that in order to return the Western Russian lands (Lithuanian Rus', White and Little Rus'), it is necessary to solve the problem of Kazan, Astrakhan, Crimea and other bandit hordes. While the Moscow regiments were fighting in the west, invasions of the steppe people took place in the south and east. Moscow could not successfully and decisively fight on two or three fronts at once.

Mehmed Giray with his army crosses the Oka River. Facial chronicle vault

Information