Poland takes revenge. The defeat of Khmelnitsky in the Battle of Berestetsky

The Battle of Berestetsky became one of the major battles of the 160th century, in which, according to various sources, from 360 to XNUMX thousand people took part. The Polish-Lithuanian army under the command of King Casimir defeated the Russian-Crimean troops of Khmelnitsky and Islam-Girey.

The defeat was largely due to the betrayal of the Crimean Khan, who arrested the hetman and withdrew his troops from the battlefield. The Cossacks, left without a commander-in-chief and without allies, went on the defensive and were defeated. As a result, Khmelnitsky had to accept the new Belotserkov Peace, which was unfavorable to the Western Russian population.

Russian liberation war

In 1648, the Russian War of Liberation began under the leadership of Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Let me remind you that no state “Ukraine” and “Ukrainian people” in this historical period did not exist. The lands of Kyiv, Novgorod-Chernigov, Galician-Volyn Rus have been inhabited by Russian-Russians since ancient times. During the period of feudal fragmentation, the southwestern Russian lands were captured by Hungarian, Polish and Lithuanian rulers. The Lithuanian-Russian princes created the powerful Great Lithuanian and Russian Principality, which was a Russian state with a predominantly Russian population (up to 90%) and the Russian state language.

Then Lithuanian Rus became part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Huge Russian regions came under the rule of the Polish kings. To designate them, they began to use the Greek name “Little Rus'”, “Little Russia”. The concept of “outskirts-Ukraine” was also used. That is, the former Kievan, Seversk and Galician Rus became “Ukrainians” of both Poland and the Muscovite kingdom. A purely geographical concept, not an ethnographic one. The way the Russians lived there is how they continued to live.

No total genocide or change of indigenous ethnic group occurred on this Russian land. Polish and Jewish communities appeared in cities and villages. Many Western Russian princely and boyar families became Polish, becoming Poles. But the general mass of the population - peasants, townspeople, clergy, Dnieper Cossacks, were Russians. They preserved the Orthodox faith, which then largely meant Russianness.

The Polish lords were unable to create a full-fledged Polish-Russian empire, a community that could have made the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the strongest power in Europe. They chose to follow the path of enslavement, both of their own peasant peasants, turned into “draft cattle - cattle,” and of the Russians. In relation to Russian Ukraine, this defeat was not only economic, but also national and religious.

The Russian people, relying on the brotherhood of the Cossacks, the clergy (especially the lower ones) and the townspeople, resisted. The Russians more than once raised uprisings, crushed the Poles and Jews (they played the role of overseers, managers, who tore off seven skins from the people). The Polish lords and authorities responded with the most brutal terror. Peasant revolts and Cossack revolts were drowned in blood.

In 1648, another uprising escalated into a real war, which Warsaw was unable to suppress immediately.

Bohdan Khmelnitsky's entrance to Kiev. Painting by Nikolai Ivasyuk, late XNUMXth century

General situation after Zborov

The Peace of Zboriv in 1649, which the Polish side signed after a severe defeat, did not become final (No peace, no war. Anxious truce after Zborov). The Polish elite did not intend to preserve the autonomy and broad rights of the Cossacks. Embassies came to Moscow and asked the Tsar that the Russian army, together with the Poles, strike the rebels. The Poles reported that allegedly Khmelnitsky, together with the Crimeans, was preparing an attack on Russia.

The tsarist government knew well what was really happening in Russian Ukraine. “Friendly” warnings were ignored. On the contrary, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich banned trade with the Poles, and ordered that duties not be collected from Russians from the Hetmanate. Moscow knew that Warsaw wanted to set Crimea against Rus'.

In turn, Khmelnitsky understood that the continuation of the people's liberation war was inevitable, and tried to find allies. A request for intercession from the Polish lordship, which was about to start a war, was again sent to Moscow to the sovereign. As a result, in 1650 both sides were actively preparing to continue the war.

The Polish lords have already made the decision to fight. Negotiations with Khmelnitsky were just simulated. Representatives of the Polish war party, among whom Pototsky, Vishnevetsky and Konetspolsky stood out, who had huge holdings in Ukraine, took over. At their proposal, a tax was approved to recruit a huge 54-strong army. The king was given the right to convene the “pospolita ruin” - the gentry (noble) militia. Andrei Leshchinsky, a protege of the magnates, was appointed crown chancellor instead of the deceased Ossolinsky, who adhered to a cautious policy and tried to strengthen royal power. Ossolinsky himself, in whose papers letters to the Cossacks of the late King Vladislav were found, was branded a traitor.

Khmelnitsky at this time sent a delegation to Warsaw. He wanted to confirm the terms of the Zboriv Treaty. He recalled the points that were not fulfilled - the abolition of the union, the return of seized property to the Orthodox Church, the admission of representatives of the Hetmanate to the Polish Senate and the Sejm.

The Cossack embassy only added fuel to the fire. Rebellious "claps" dare to give orders to high-born gentlemen! On December 24, 1650 (January 3, 1651), the Polish Sejm broke the peace and resumed hostilities. Khmelnitsky in Poland was called “the sworn enemy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who swore to its destruction, contacts Turkey and Sweden and raises the peasants against the gentry.” The Polish authorities levied an emergency war tax with brutal measures. They recruited mercenaries. The king declared the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish-Lithuanian troops gather on the border of the Hetmanate.

Death of Nechai

In January 1651, in Chigirin, Khmelnitsky held a meeting with colonels and Cossacks. The Rada was sentenced to fight back the Polish lords and call the Crimeans for help.

In February, Polish troops led by the full hetman (deputy commander-in-chief of the army) Martyn Kalinovsky and the Bratslav governor Stanislav Lantskoronsky invaded the Bratslav region and attacked the town of Krasne (Red) in Podolia. The Cossacks of the Bratslav regiment, led by Colonel Nechai, were celebrating Maslenitsa at that time and did not expect an attack. Superior enemy forces rushed into Krasne. In this battle, Khmelnitsky’s friend and faithful comrade-in-arms, Danilo Nechai, lost his life. Contemporaries noted his “extraordinary courage and intelligence,” and the Cossacks gave him first place after Khmelnitsky.

The Poles, as usual in such a situation, were noted for atrocities and torture. Nechay’s wife was declared a witch, wildly tortured, dragged naked into the square and impaled. It was the turn of other townspeople to follow her. They tortured women and children, and did not spare the young and old. The entire town was slaughtered.

In the same way, villages were destroyed along the way. Kalinovsky captured and slaughtered the towns of Shargorod and Yampol. At the end of February 1651, Polish troops besieged Vinnitsa, where Ivan Bohun stood with 3 thousand Cossacks. The colonel already knew about the invasion and fortified himself.

Russian Cossacks, townspeople and peasants gave support to the gentry. Khmelnitsky sent the Uman regiment of Osip Glukh and the Poltava regiment of Martin Pushkar to help Bohun. The nobility was afraid to accept the battle and retreated. Not far from Vinnitsa near Yanushintsy, Bohun’s Cossacks defeated the enemy. The remnants of the Polish troops fled to Bar and Kamenets-Podolsky.

"Lithuanian affair"

In Russia, a Zemsky Sobor was immediately convened on the Lithuanian affair. It opened on February 19, 1651, and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich ordered that “past and current grievances” be announced to the delegates of the Polish king, and that the Zaporozhye hetman Bogdan was beating his forehead on citizenship to the Russian Tsar. The highest body of the Russian kingdom spoke unanimously: in favor of a break with Poland and the adoption of Little Russia under the authority of the sovereign.

Moscow was still biding its time and was not ready for a complete break with Poland. The Tsar did not bring two important issues to the Council: the collection of an emergency tax on the army and the entry into the war itself. However, the decision of the Council was already preparing Rus' for war.

The Russian authorities are helping the Cossacks openly. Shokhov's Chernigov regiment was allowed to pass through the Bryansk district and was given guides. Peasants were mobilized to repair bridges. A 6-strong detachment of Cossacks passed through the land of the Russian kingdom and struck the enemy in the rear, taking Roslavl and Dorogobuzh. The Lithuanian authorities are forced to transfer troops to this direction. Hetman Radziwill reported to Warsaw that there were plenty of Moscow troops near the Lithuanian borders and asked for reinforcements.

But Moscow did not have time to enter the war during this campaign. Events developed very quickly. This time Warsaw and the Catholic clergy did a good job. The magnates with their banner regiments were not late, did not refuse the war, and spurred on the small gentry. A large army was quickly assembled near Lublin. A golden sword was sent from Rome, consecrated by the pope himself. In April, the papal nuncio Torres girded the king with a sword. The Pope absolved all participants in the campaign from all sins, both past and future.

Khmelnitsky publishes a universal in which he announces to the people about a new war and calls on people to rise up against the Poles. Mobilizes regiments and prepares military supplies. People with station wagons were sent to Poland, in which the peasants were called upon to rebel against the gentry. In the Carpathian region, the uprising was led by Kostka Napersky. On June 16, the rebels captured Czorsztyn Castle near Nowy Targ. Lubomirski's Polish detachment took Czorsztyn Castle, the leaders were executed, and the uprising was drowned in blood. However, unrest among the peasants continued.

The people of White Rus' also rose up to fight the Polish occupiers. Bogdan sent a 20-strong detachment of Colonel Martyn Nebaba to the Lithuanian front.

Khmelnitsky again asks for help from the Crimean Khan, but he hesitates. Finally, he sends part of the troops with the vizier, orders them not to rush into battle and, if the Poles take over, to hastily leave for the Crimea. The hetman marches with troops from Chigirin to Bila Tserkva, and from there further towards the enemy. Khanu again sent a letter of petition and promised money. Khmelnitsky, who was tormented by personal doubts (he suspected his wife Elena Chaplinskaya of betrayal), hesitated on what to do: go further against the enemy or make peace?

A new council was convened in May. The Cossacks, peasants and townspeople were united: war, even if the Crimeans retreat: “either we will all die, or we will exterminate all the Poles.”

The forces of the parties

Due to the slowness of the Crimeans, Khmelnitsky refused to attack for more than a month. The elders who led the army, Kropivyansky Colonel Filon Dzhedzhaliy, Bratslav Colonel Bohun, Mirgorod Colonel Matvey Gladky, Umansky Colonel Joseph Glukh and others insisted on immediately attacking the enemy, without allowing the gentry to prepare for battle. Khmelnitsky himself wanted this, but showed indecision, hoping for the arrival of the Crimean Horde with the khan, who promised to come soon.

Islam-Girey was in no hurry; instead of an easy walk and robbery, a battle with a strong and well-prepared enemy awaited him. Tatar spies reported a huge Polish army. This news alarmed and angered the khan. In vain did the hetman convince him that this was not the first time for the Cossacks to smash the Poles.

In June 1651, Khan Islam-Girey united with the Cossacks. According to various sources, the Tatar army had 25–50 thousand horsemen (the Poles believed that the Crimeans had an army of 100 thousand). The peasant-Cossack army numbered about 100 thousand people - about 45 thousand Cossacks (16 regiments, each with about 3 thousand Cossacks), 50-60 thousand militia (peasants, townspeople), several thousand Don Cossacks, etc.

The Polish army numbered, according to various sources, from 60 to 150 thousand people - the crown army, the Commonwealth and mercenaries (12 thousand Germans, soldiers from Moldova and Wallachia). Plus a large number of armed servants and servants of the lords and gentry. The Polish king Jan Casimir divided the army into 10 regiments. The first regiment remained under the command of the king, which included Polish and foreign infantry, court hussars and artillery. In total there are about 13 thousand people. Other regiments were headed by crown hetman Nikolai Pototsky, full hetman Martyn Kalinovsky, governors Shimon Szczawinsky, Jeremiah Vishnevetsky, Stanislav Pototsky, Alexander Koniecpolsky, Pavel Sapieha, Jerzy Lyubomirsky and others.

Tragedy of Hops

Two large armies converged near the town of Berestechko on June 17–18 (June 27–28), 1651. The place where the battle was to unfold was a flat quadrangle formed near Berestechko by the flow of the Styr River with its tributaries Sitenka and Plyashevka. Rivers, swamps, forest islands and ravines made it difficult for troops to move. The royal troops settled over the Styr River near Berestechko, the Poles took up convenient positions and fortified themselves on the heights. Russian-Tatar troops settled on the western bank of the Plyashevka River, above the village of Soloneva. The horde of the Crimean Khan set up a separate camp.

At this time, Khmelnitsky experienced a great personal tragedy. Previously, he regained the Subbotov farm, and managed to return the beautiful Polish woman Elena, who was taken away by Chaplinsky. She, naturally, assured the hetman that she still loved him. Her Catholic marriage was forced and therefore invalid. Elena became Khmel's wife. But the person turned out to be stupid and frivolous. The eternal plot of “an old woman at a broken trough.” The hetman's wife did not appreciate the happiness that had fallen. She drank, partied and cheated with the gentlemen who hung around the eminent person.

It was impossible to hide this; rumors reached the hetman. But he loved passionately, did not believe, and considered rumors and denunciations to be slander. But Bogdan’s son Timosh hated his young stepmother. I was indignant at how she was deceiving and disgracing her father. In the end, I decided to act on my own. When the hetman led the army, Timosh paused to gather reinforcements. Then he came to the farm and caught Elena “warm”. He ordered his stepmother and lover to be hanged naked from the gate.

Khmel learned about this on the eve of the battle and was greatly shocked. He started drinking out of grief. The colonel and the Tatar Murzas began the battle without him. They attacked disorganized, without a common command, and suffered heavy losses.

Battle

On June 17–18, 1651, clashes between the Tatars and Cossacks with the detachments of Konetspolsky and Lubomirsky took place. Islam-Girey proposes to retreat, the Cossacks - for the battle. On June 19 (29), the Cossacks, under the cover of fog, crossed and approached the royal camp. The Cossack attack was supported by a small detachment of Crimeans. The Polish cavalry, supported by infantry, counterattacked and tried to outflank the Cossacks. The Cossacks were able to cut off and smash the enemy's left wing. The Cossacks obtained 28 banners (banners of individual units), including the banner of Potocki.

The Crimean Khan, having sent small detachments to help the hetman, waited with the rest of the troops for the outcome of the battle. By evening the battle died down, there was no winner. The Poles suffered significant losses. Entire banners (detachments) and their commanders perished. But both the Cossacks and the Crimeans suffered noticeable losses. Khmelnitsky's old comrade-in-arms, the Perekop Murza Tugai Bey, died, which was perceived by the Crimeans and the khan as a bad sign.

Islam-Girey, who was a zealous Muslim, despised drunkenness, began to yell at the Cossacks:

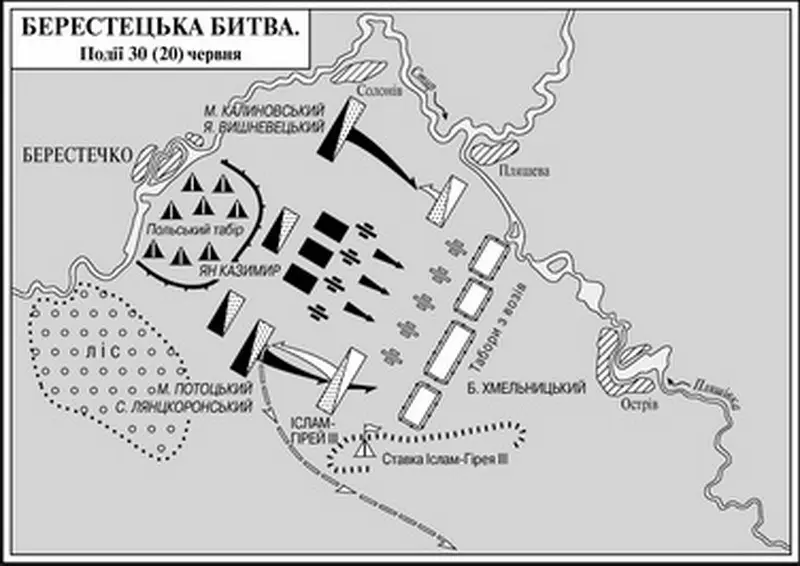

On June 20 (30), 1651, the parties lined up for the decisive battle. Among the Poles, the right wing was led by Pototsky, the left by Kalinovsky, and the king with infantry stood in the center. The battle did not begin in the morning; both sides waited until lunchtime. Khmelnitsky and the foreman decided that let the gentry attack first, destroy their battle line, the Cossacks would repel the enemy’s onslaught in a moving fortress of carts connected by chains, then counterattack.

With the permission of the king, the attack was launched by the Vishnevetsky regiment (under his command there were 6 banners of registered Cossacks), followed by the regiments of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish cavalry broke into the Russian camp. Khmelnitsky personally raised the Cossacks to counterattack. The ranks of the Polish cavalry were mixed, the Poles retreated. The Cossacks themselves went on the attack, but they were also driven back.

At this time, the Crimean Tatars continued to be inactive, only pretending that they wanted to attack the enemy. When the royal regiments rose against them, the Crimeans immediately retreated. In the evening, the Polish quartz army (regular units), supported by artillery, demonstrated towards the Crimeans. The Tatars suddenly took to their heels, having thrown their camp. Thus, the Crimeans opened the left flank of the Cossacks. It was so unexpected that it confused everyone. Khmelnitsky, having transferred command to Dzhedzhaliy, rushed after the Crimean Khan. I caught up with him after a few miles.

Khmelnitsky tried to convince Islam-Girey to continue the fight and not leave him. But the khan was determined. The hetman was captured, and the horde hastily walked along the Black Road to the Crimea, plundering and destroying everything in its path. Khmelnitsky was taken as a prisoner. There were rumors that the Poles bribed the khan to withdraw the army, and also offered to rob part of Ukraine along the way. Khmelnitsky was held captive for about a month, then they took a large ransom and released him.

Painting “Hussar” by Jozef Brandt. 1890

Siege and defeat

The Cossack-peasant army, finding itself without a hetman and allies, went on the defensive. The Cossacks moved the camp to the swamps near the Styri Plyashevka tributary, fenced it with carts, and built a rampart. The Russian camp was blocked on three sides by the Polish army. On the fourth side there were swamps, they protected from the enemy, but also did not allow retreat. Several gates were built across the swamp, which made it possible to obtain provisions and fodder. But a large army began to starve.

The hostilities were limited to skirmishes, forays of the Cossacks, the Poles brought up artillery, began shelling the camp. Cossack artillery responded with their fire. Dzhedzhali, Gladky, Bohun and others were in charge of the defense. On June 27 (July 7), the Polish king suggested that the Cossack ask for forgiveness, hand over the colonels, the hetman's mace, guns and fold weapon. On June 28 (July 8), Philon Dzhedzhaliy was elected hetman, against his will. The Cossacks refuse to surrender and demand compliance with the Zboriv Treaty. The Poles continue their artillery shelling.

On June 29 (July 9), the Cossacks learned that Lanckoronsky’s detachment was bypassing them, which threatened complete encirclement. The elders send a new delegation to the king, but Hetman Pototsky tears up the letter with their conditions in front of the king. A participant in the negotiations, Colonel Rat, who went over to the side of the king, proposes to build a dam on the river. Plyashevka and drown the Cossack camp.

On June 30 (July 10), Colonel Bohun was elected as the new hetman. He decides to lead the attack against Lanckoronsky and pave the way for the rest of the troops. At night his regiment began crossing. To expand the gates, they use everything they can - carts, their parts, saddles, barrels, etc.

The peasant-Cossack troops began to leave through these roads. At the same time, the Poles began their offensive. The Cossacks desperately resisted. A small detachment of 300 fighters covered the withdrawal of the main forces and was completely killed. Nobody asked for mercy. In response to Pototsky’s promise to give them life if they laid down their arms, the Cossacks, as a sign of disregard for life and wealth, in front of the enemy’s eyes, began to throw money and jewelry into the water and continued the battle.

According to Polish sources, chaos broke out during the crossing, bridges collapsed, and many drowned. However, part of the troops led by Bogun broke through and escaped. The Poles believed that about 30 thousand Cossacks died. It is obvious that the Poles exaggerated their victory.

Berestetskaya battle, triumphal panel of King Jan II Casimir. Tomb of King Jan II Casimir in Saint-Germain Cathedral, Paris

Belotserkovsky world

The Polish command was unable to use the victory at the village of Berestechko to end the war in their favor. The gentry's militia collapsed, many lords and nobles announced that they were tired, spent money, and went home without royal command. King Jan Casimir also left to celebrate the victory. It seemed that this was already a decisive victory, the uprising would be crushed, and everything would be as before.

Only part of the Polish army (crown troops and squads of magnates) continued the offensive, betraying everything in its path to fire and sword. The army was led by Vishnevetsky and Pototsky. Radziwill's 40-strong Lithuanian army was advancing from Belarus. The Lithuanian hetman crushed the regiment of the Chernigov colonel Nebaba, which was dominated by peasants, and captured Kyiv. The city was plundered and burned. Nebaba soon died in the battle of Loev.

Mass terror over civilians also had the opposite effect. The Russians realized that there would be no mercy. They became bitter and fought to the death. The surviving villagers and townspeople formed detachments and destroyed small Polish units. Numerous new detachments were formed around the surviving Cossack atamans and even ordinary Cossacks. Radziwill, realizing that he would soon be surrounded, left Kyiv and went to join Potocki.

After the ransom, Khmelnitsky himself was able to show iron will and reason. He pulled himself together and overcame personal tragedy, defeat and death of his comrades. Essentially, I started over.

He called people to arms and again gathered large forces. The army was revived literally in a matter of weeks. The Poles begin to meet strong resistance in every town. Cossack detachments appear in the enemy rear, recapture Vinnitsa, Pavolochi and Fastov.

It is becoming increasingly difficult for the Polish army to obtain provisions and fodder in a devastated and burning country. There were no reinforcements from Poland. The war led to an epidemic that decimated the soldiers. In August, the most implacable enemy of the Russians in Little Rus', Prince Yarema Vishnevetsky, died. Without his iron will and the hand that held the soldiers, the army began to fall apart. The gentry and mercenaries demanded to return home and could start a rebellion.

As a result, Khmelnitsky was able to stop the enemy’s advance near Bila Tserkva in September. Negotiations began. The new Peace of Belotserkov was signed.

The register of Cossacks was reduced by half, to 20 thousand Cossacks. Registered Cossacks could live only on the territory of the Kiev Voivodeship. The gentry returned to their Ukrainian estates. Polish troops were stationed in Little Russia. The Zaporozhye hetman was subordinate to the Polish crown hetman, had no right to negotiate with other states and terminated the alliance with Crimea.

A new stage of the war was inevitable.

Prince Jeremiah (Yarema) Mikhail Korybut-Vishnevetsky (1612, Lubny - August 20, 1651, camp near Pavoloch) - statesman and military leader of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the Vishnevetsky family, Russian governor (1646–1651)

Information