Expedition to the ancestors. When ethnography comes to the rescue

man of the fields,

and Jacob was a quiet man,

living among the tents.

Genesis 25:27

Migrants and migrations. Today we will interrupt our story about the events of the ancient stories humanity, in order to refer to what took place quite recently, some 70 years ago. And the reason for this is that in comments to past materials, a number of our readers made statements that the people of that distant time were only thinking about what they could eat. That is, they say, they simply didn’t have enough time for “culture,” because “the hungry belly is very deaf to art.” However, is this not really the case?

Already ancient paintings in caves of the Paleolithic era prove that people already had enough time for this “useless activity”, that while someone was hunting there, someone else was painting mammoths in the cave, and there were also those who mixed paints for him and “held a candle.” However, we are not destined to find out how everything was there in the Paleolithic.

But we can find out how it could have been already in the Bronze Age by turning to the data of ethnography - a science that studies peoples-ethnic groups and other ethnic formations, as well as their origin (ethnogenesis), settlement, and what is especially important for us in this case – their cultural and everyday characteristics. That is, to put it simply, you need to look at how peoples live today who are at approximately the same level of development as people of the era of megalithic cultures, as well as of later times.

We will have quite a large choice here, but we will go to the island of Borneo or, as it is now called in Indonesia, Kalimantan, where two peoples lived and live, the Dayaks and the Punans. Moreover, the famous French zoologist Pierre Pfeffer, the author of the most interesting book “Bivouacs in Borneo,” which was published in the USSR in Russian by the Mysl publishing house, will tell us about them.

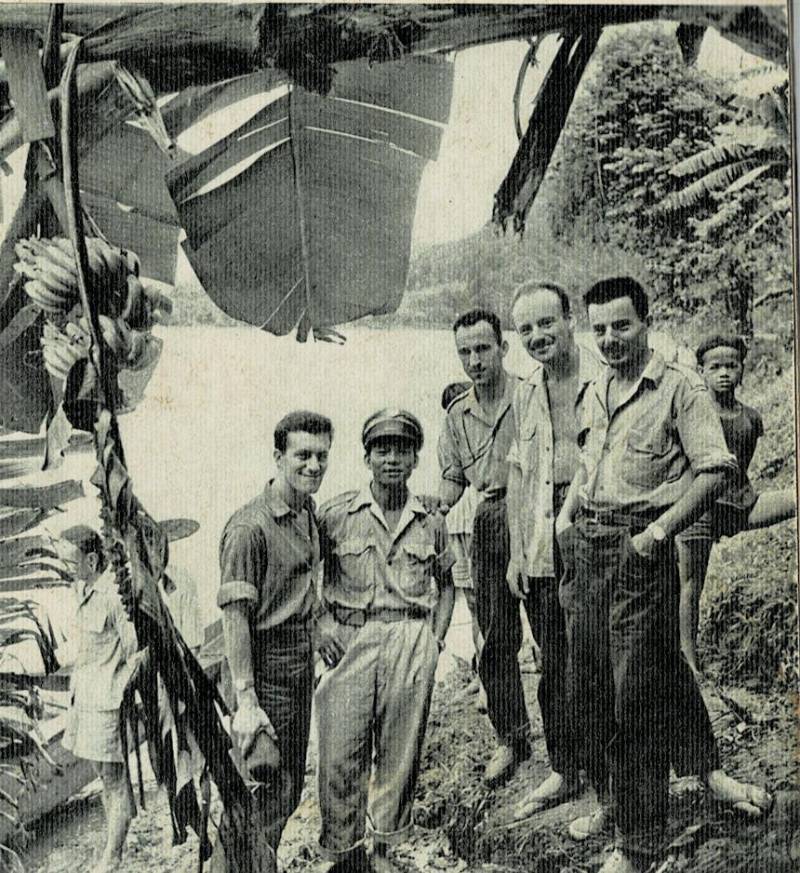

Pierre-Pfeffer (far right) and members of his expedition along with an Indonesian policeman (in uniform)

And it so happened that Pierre Pfeffer was part of the French expedition in 1962–1963. visited the island of Borneo, and in this book he described everything that he saw and experienced. Now I don’t remember how they bought it for me, but only then I asked more than once to read it to me, and my mother read it to me. So already as a child I learned it almost by heart, and then, as an adult, I re-read it several times.

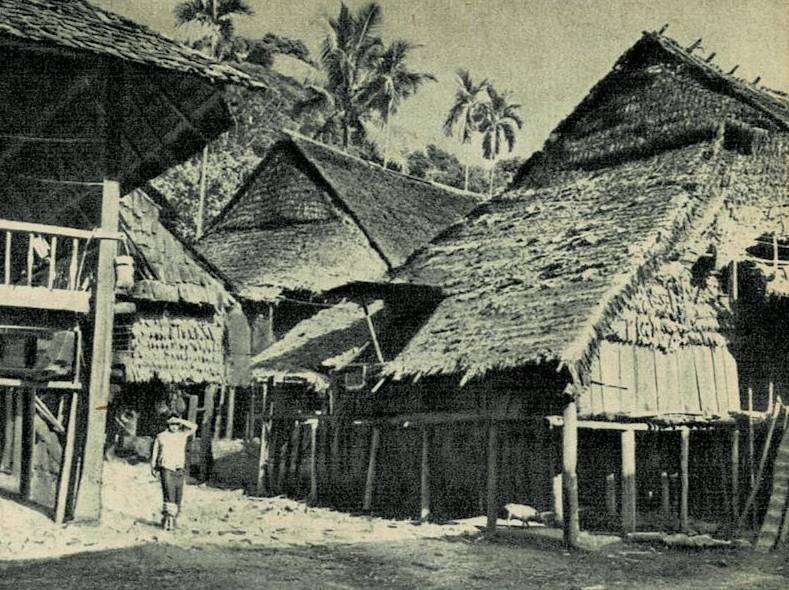

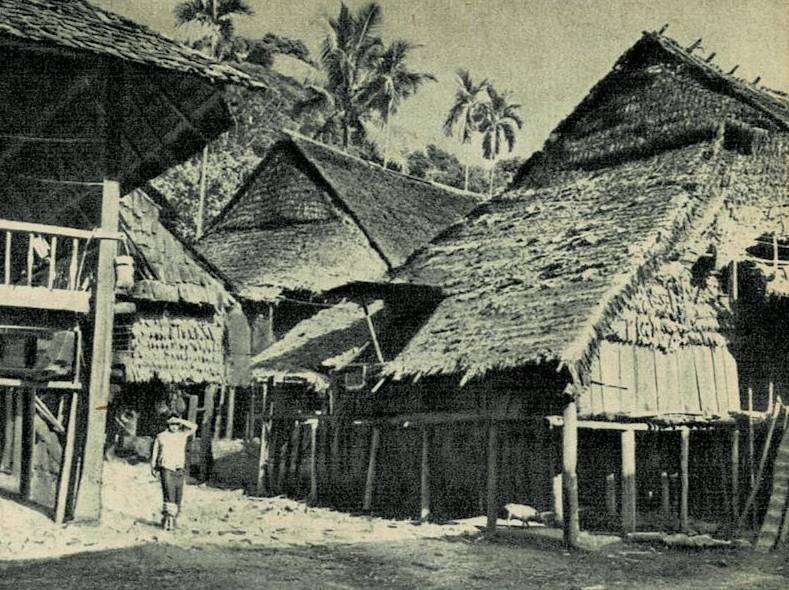

Dayak houses in the village. Photo from Pierre Pfeffer's book "Bivuacs in Borneo"

Pfeffer caught and dissected local animals, but an equally important part of his work was to go hunting and supply the expedition with meat. And, of course, he actively participated in the life of the Dayaks and described their life and way of life in great detail.

Briefly, and even in relation to our topic, we can say that at the time when he came to them, the Dayaks lived in the very early Iron Age. Moreover, even in the 1950s they combined metal tools with stone ones.

Their agriculture was slash-and-burn. They cut down a piece of the jungle, waited for the trees to dry out, and either cut them down into planks or simply burned them. And then they planted rice there, which was the main food product, and they also made vodka from it. They also grew bananas, ate young bamboo shoots, and sowed corn, sago, cassava, cucumbers, pumpkins, and millet.

Pets: dogs, chickens, pigs. The latter were not much different from wild boars, except that they lived among people. In addition, the Dayaks lived by hunting and fishing. The fact is that their villages were located along the banks of rivers, which were the only acceptable road through the jungle.

The Dayaks make plates from bamboo trunks. Photo from Pierre Pfeffer's book "Bivuacs in Borneo"

The houses are communal, 100–200 m long, and can accommodate up to 50 families of 5–6 people. Houses on stilts made of ironwood, walls made of bamboo, roofs made of palm leaves.

Next to it is a barn of the same design. Initially, the villages were surrounded by a high fence made of bamboo trunks, since the Dayaks constantly fought among themselves. But Pfeffer no longer found these fences.

Tools and weapon they had the most primitive things: a blowpipe - a sarbakan, which fired an arrow poisoned with cobra venom, a spear with a bronze, copper or iron tip and a traditional mandou sword.

The hardest work for them was cutting down trees and hewing boards from them for houses. They hewed only two boards from one trunk of a thick tropical tree. They could hollow out a solid wooden pirogue 20–30 m from it.

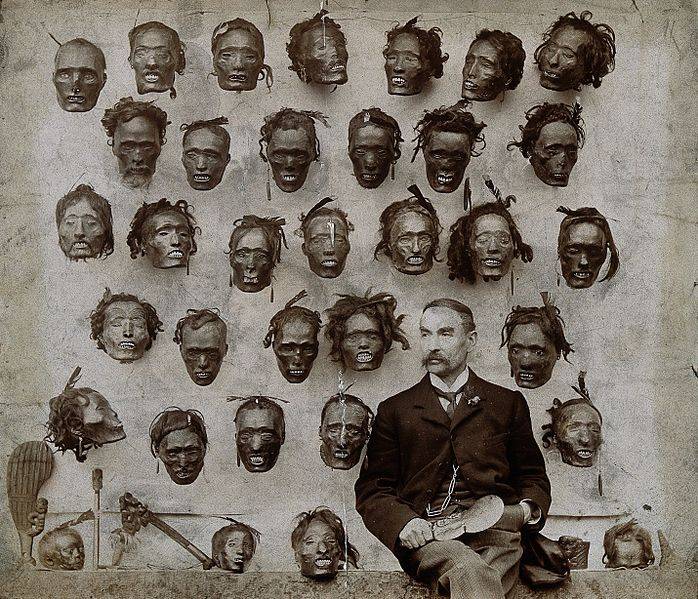

Heads of Punan - inhabitants of the central regions of Borneo, cut off by "sea Dayaks" from the coast

In the past, the Dayaks followed strange traditions. So, not a single Dayak could get married without presenting his severed head to the bride! It doesn't matter men, women or children. The main thing is that from a foreign, hostile tribe. Therefore, intertribal enmity caused by such “headhunting” did not subside there for a very long time. The heads were dried, smoked and stored as heirlooms.

The last time there was an outbreak of “cutthroatism” was during the Second World War, when the Japanese paid the Dayaks for the heads of whites, and the whites for the heads of the Japanese, but since the Americans and British paid more, the Dayaks chose their side. True, getting married has become more difficult! If previously they demanded one head, now a warrior who had even twenty dried Japanese heads was no longer valued as much as before.

Europeans also collected these terrible souvenirs. Horatio Robley with his collection of severed heads

And so, judging by archaeological data, similar houses (but not made of iron wood, of course!) were built during the Chalcolithic era in Scandinavia, and in Poland, and in other places. Or houses were stuck to one another if they were built from stone or clay bricks.

And their economy, judging by the bones and grain finds, was similar. And they hunted in the same way. So this is how successful hunting was among the Dayaks and how successful it could have been among the people of that time. It should be emphasized that the Dayaks hunted large animals exclusively with spears, that is, in general, the same way as their distant ancestors.

By the way, megalithic buildings have also been discovered in Borneo. Only there, as we see, the development of civilization proceeded very, very slowly.

Pfeffer himself hunted with a Brno carbine of 8,57 mm caliber, and the Dayaks willingly invited him to hunt, since he always gave half of the carcass and the head to the Dayak accompanying him. Their hunt was not always successful, and sometimes, having gone into the forest in the morning, they returned back only at six o’clock in the evening, having walked more than 10 km with parts of the carcass... 50 kg each, which they had to drag on their backs!

Then he and his comrades ate meat for two days, and then it ran out, and then they had to eat rice or buy village chickens. When he came with prey, the Dayaks immediately came to him and asked for meat, but not very much. Moreover, this was how they addressed everyone who caught wild boar, so that everyone in the village ate the meat, although sometimes there was very little of it, and sometimes they literally gorged themselves on it.

This is what the Dayaks looked like somewhere in the early 50s of the last century. National Museum of Collectibles and Culture, Amsterdam

Here is his story about one of his meetings with a group of Dayak hunters:

Then everyone began to put pieces of meat on them, carefully making sure that everyone got a piece of heart, liver and lard.

As a result, there was a pile of skewers in front of us, which were then divided equally among everyone present.

The skewers were wrapped in reed leaves, after which the hunters jumped into the pirogues and went to their families.”

Dayak hunter with a boar on his back

Of course, Borneo is tropical. There were wild boars, deer, rhinoceroses, crocodiles, panthers - whoever was there.

But in Europe there were plenty of all kinds of animals. The same wild boars, deer, elk, roe deer, aurochs and bison, wild goats, rams, saigas in the steppes. Yes, who was not in her forests then? There were a lot of birds! In particular, the first settlers in America wrote that they sent a boy with a stick into the forest to catch birds for dinner, and he, having found a tree where black grouse were sleeping in a row, simply beat them with a stick, and always managed to kill a couple of them before the rest flew away.

They fired cannons at flocks of wood pigeons, these flocks were so large. And look how many deer heads with antlers are on display in the knightly castles of the Czech Republic and Germany. There are also records there of how many different animals their owners caught.

But there were also annual migrations of animals...

So in Borneo, twice a year, in July-August and December-January, wild boars migrate en masse from north to south Borneo. They travel in small groups or herds, sometimes numbering several hundred animals. At the same time, they always follow the same paths, and cross rivers in certain places. It is clear that the Dayaks know these places and kill them en masse there.

As soon as the news spreads through the villages that “boars are swimming,” the male population immediately abandons all their activities and, armed with spears and ancient muskets loaded from the muzzle, hides on the shore, opposite the bank from where the pigs come.

Single animals are allowed through, but as soon as a herd enters the water, the hunters sit in the pirogues and spear the boars. Wounded animals and corpses are carried away by the current, and further down the river they are picked up by other hunters and even women and children.

Young Dayak beauty with elongated earlobes

The first boars are eaten whole. But then only a layer of fat is removed from them, and the rest... is thrown into the water. Well, the lard is drowned and kept in reserve, pouring it into jugs, bamboo pipes or canisters. The Dayaks used some of this lard themselves, but most of it was sent to the coast, where it was sold to Chinese traders at a thousand francs per twenty liters.

And there was so much of this lard that in December 1956 - January 1957, residents of the village of Long Pelbana on Kayan even caulked several large pies, placed them on stands and filled them to the brim with rendered lard.

The dead boars were thrown into the bay by the river current, where their corpses attracted many sharks and crocodiles. And they, decomposing in the sun, poisoned everything around with their miasma, so the coastal inhabitants went to war against the forest Dayaks to force them to stop beating the wild boars, and government intervention was required to stop this war.

And who can say whether the same thing did not happen in our distant past, when there were few people in Europe, but, on the contrary, there were many animals?!

And also there in Borneo lived the Punan tribes - hunter-gatherers, and Pierre Pfeffer also went to them and lived among them.

They are still engaged in hunting, collecting wild fruits and dammar resin, which they exchange for grain and tobacco. They hunt monkeys, wild boars, deer, bears, panthers, rhinoceroses and game birds. Women also collect wild sago fruits.

In hunting they use the same blow pipes, spears, traps, traps. They live in forests in huts and have no permanent settlements.

Dayaks today (2008 photo)

That is, in front of them is nothing more than a piece of our past.

And here’s what’s interesting: the same Punans eat much worse than the Dayaks, but they are engaged in wood carving and music (!), they have enough time to get a tattoo and rings in their ears.

So it is unlikely that our distant ancestors, both in Asia and in Europe, lived worse than the Dayaks and Punans. This means that they had enough time for absolutely everything, and not just for hunting and eating!

Information