The heroic death of the post of St. Nicholas

General situation at the Caucasian Theater

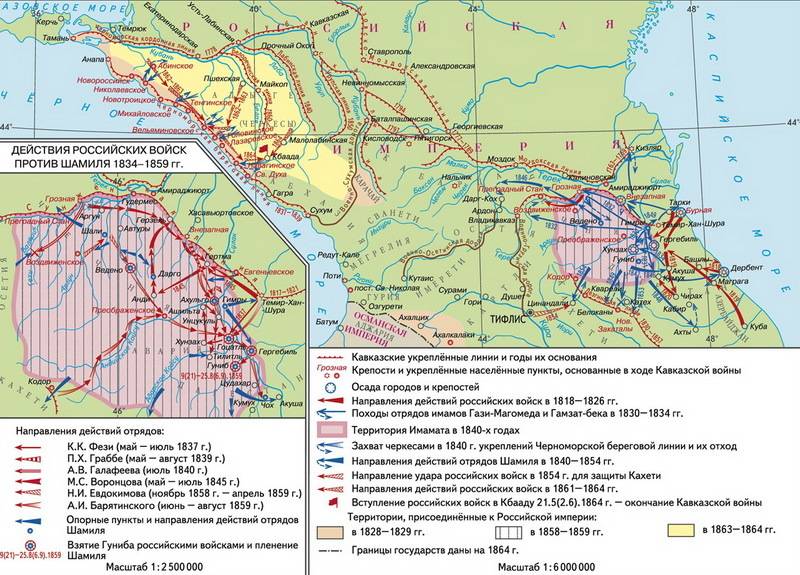

The Crimean (Eastern) War began as another Russian-Turkish War (How Türkiye opposed the “gendarme of Europe”). As in previous conflicts between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, the Caucasus became a battlefield. Istanbul had many territorial claims against Russia. The Ottomans wanted to recapture not only the Crimea and the South Caucasus. They recalled the once Turkish possession of the coast of Russia, Abkhazia, Circassia, as well as other regions of the North Caucasus.

The main difficulty of the war in the Caucasus was the enormity of the region, its borders, the underdevelopment of communications in this mountainous area and the danger of war not only with Turkey, but also with Persia (Iran). Persia could act against Russia at any moment, seizing an opportunity for this. Therefore, it was necessary to keep troops in the Persian direction.

Relations with the local population were also difficult. A long and bloody war was continuously going on with part of the mountain tribes of the North Caucasus. It either died down or flared up again. Some of the mountaineers were gradually drawn into peaceful life, finding more benefits in it than from constant massacres. Others were ready to start fighting at any moment.

The Armenians at this time were betrayed to the Russian authorities, since only the Russian army saved them from slavery and complete destruction. They remembered this very well. Armenians dreamed of uniting all historical Armenia under the wing of the Russian Tsar. Most of ancient Armenia was then under Ottoman rule. A significant part of the “Tatars” (as the Muslims of Transcaucasia were called) also supported Russia.

For most of the Georgians, except for part of the nobility, who wanted the opportunity to rule over the common people and were ready to betray Russia at any moment, the war with Turkey was a continuation of a century-long struggle against a merciless “hereditary” enemy, from which only the Russians saved Georgia. Russia was the guarantor of life, security and prosperity. Also, under the rule of the Russian Tsar, there was a reunification of historical Georgia, the formation of the Georgian people from individual nationalities and tribes.

Defeat the Highlanders

A serious threat to the Russian army was a strike from the rear. Georgia, Guria, Mingrelia, Abkhazia were separated from the rest of the Russian Empire by a huge mountain range and warlike mountain tribes, this made them vulnerable. The highlanders, excited by foreign emissaries, posed a significant danger. However, Shamil hurried and opened hostilities first, even before the Ottoman army arrived.

Shamil and the naib of Circassia and Kabardia, Mohammed-Amin, gathered the mountain elders and announced to them the firmans received from the Turkish Sultan, which commanded all Muslims to start a war against the “infidels.” The mountaineers were promised the imminent arrival of Turkish troops in Balkaria, Georgia and Kabarda. Russian troops, in their opinion, were weakened by the need to guard the Turkish borders.

On September 5, 1853, Shamil’s 10-strong detachment appeared near the village of Zakartaly (Zakatala) in the Alazani Valley. On September 7, Shamil with the main forces attacked an unfinished redoubt near Mesed el-Kera. The position of the Russian garrison was desperate. He was rescued by a detachment of the commander of the Caspian region, Prince Argutinsky. The prince made an unprecedented forced march from Temir-Khan-Shura directly through the mountains. Shamil was forced to retreat. After this, the mountain leader remained inactive until 1854, awaiting decisive successes of the Ottoman army.

The performance of the Circassian Naib also ended in failure. Mohammed-Amin with significant forces moved to Karachay, where many like-minded people were awaiting his arrival. This was supposed to lead to a large-scale uprising. The commander of the troops on the Caucasian line and in the Black Sea region, General Vikenty Kozlovsky, saved the situation. The brave general, with only three battalions, rushed after Mohammed-Amin and, just before Karachay, completely defeated the Trans-Kuban highlanders. Then he set about constructing the road to Karachay, so that it could be done in a very short time. As a result, further development of the uprising was prevented.

The Russian command had to reckon with the threat from the mountaineers and keep part of its forces on the border with the North Caucasian tribes. With the beginning of the war, the Russian command had to abandon the offensive strategy and switch to defense. Deforestation, road construction, and deprivation of the mountain people's means of subsistence continued, but on a more limited scale.

Raid of mountaineers on a Caucasian farm. Artist Franz Roubaud

The forces of the parties

At the beginning of the war with Turkey, Prince Mikhail Vorontsov was the Caucasian governor. Hero of the War of 1812 and the Foreign Campaign, Vorontsov was appointed commander-in-chief of the troops in the Caucasus and governor of the Caucasus in 1844. Under the leadership of Vorontsov, Russian troops continued their offensive against the mountain tribes. The governor was loved by ordinary soldiers. For many years, stories about the simplicity and accessibility of the Supreme Governor were preserved among soldiers in the Russian army in the Caucasus. After the death of the Caucasian governor, a saying arose in the Caucasus: “God is high, the Tsar is far away, but Vorontsov is dead.”

However, by the beginning of the Eastern War, Vorontsov had already exhausted the physical potential God had given him. At the beginning of 1853, the prince, feeling the approach of blindness and extreme loss of strength, asked the emperor to resign (Vorontsov died on November 6, 1856). On March 25 (April 6) Vorontsov left Tiflis.

In St. Petersburg they did not understand the full danger of the situation in the Caucasus. Initially, Nikolai Pavlovich was confident that Russia would have to fight only with the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian army would easily win this campaign. In mid-October 1853, the Black Sea Fleet transferred the 13th Infantry Division (16 thousand bayonets) to Georgia by sea. The sovereign wrote to the governor, who did not at all share the tsar’s optimism and was very afraid for the region entrusted to him:

Nikolai suggested that Vorontsov repel the first enemy attacks and launch a counteroffensive, taking Kars and Ardahan.

In the spring of 1853, in the Caucasus there were only 128 infantry battalions, 11 cavalry squadrons (Nizhny Novgorod Dragoon Regiment), 52 regiments of Cossacks and mounted local militia, 23 artillery batteries with 232 guns. It seemed that this was a strong army capable of crushing the enemy. However, the troops were dispersed over a vast area. Some units defended the border with Persia, others protected peace in the North Caucasus. In the Turkish direction, our troops numbered only 19½ battalions, two divisions of Nizhny Novgorod dragoons and a small number of irregular cavalry, which included local residents. The main Russian forces were based in the fortresses of Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalaki, Alexandropol and Erivan.

However, the Russian Caucasian Army had extensive experience in military operations in the mountainous conditions of this region. Russian soldiers and commanders in the Caucasus were constantly in danger, expecting an attack by the highlanders, a raid by robbers from abroad, or a war with the Ottoman Empire and Persia. The harsh and military conditions of life in the Caucasus promoted decisive, strong-willed and proactive commanders aimed at active offensive actions to responsible positions. Weak and indecisive officers dropped out, could not stand serving in the Caucasus, and looked for warmer places. All this had a most positive impact on the Caucasian campaign.

The fortress of Alexandropol (Gyumri) formed the central stronghold of the operational base of the Russian army and was opposite the main Turkish fortress of Kars, located about 70 versts from it. On the right flank of this support base was the Akhaltsykh fortress, which covered the Ardagan direction. On the left flank stood the Erivan fortress; it covered the southern part of the border, from the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the roads leading from Bayazet, through the Chingil Mountains and the Araks River.

All three fortresses were very weak and could not withstand a proper siege. In addition, they had small garrisons. On the coastal road from Batum to the Russian border there was a post of St. Nicholas. Its garrison was negligible and the outpost was poorly prepared for defense. True, due to the underdevelopment of communications, its capture could not provide any benefits to the enemy for a further offensive.

With the beginning of autumn, parts of the detachments of Prince Argutinsky-Dolgorukov from Zagatala and Prince Orbeliani from the Lezgin line were transferred to Alexandropol (the most dangerous direction). The remaining three divisions of the Nizhny Novgorod Dragoon Regiment and one battalion of the Kurinsky Regiment were sent to the same area from Chir-Yurt and Vozdvizhensky.

The formation of the strike group began. Initially, Vorontsov planned to lead the offensive of the Russian troops, but illness prevented him from starting the campaign.

With the transfer of the 13th Infantry Division and the organization of the 10-strong Armenian-Georgian militia, the situation improved somewhat. A 30-strong army group was formed under the command of Lieutenant General Prince Vasily Bebutov. Part of the forces of the 13th Infantry Division with a small detachment of irregular cavalry was located in the Akhaltsykh direction. These troops were led by the Tiflis military governor, Lieutenant General Prince Ivan Andronikov.

But the enemy still had complete superiority in forces. The Ottoman command concentrated a huge invasion force - a 100-strong army under the command of Abdi Pasha. A 25-strong corps with 65 guns stood in Kars, a 7-strong detachment with 10 guns in Ardahan, a 5-strong detachment with 10 guns in Bayazet. For the offensive, the Turkish command formed two strike groups: the 40-strong Anatolian Army was preparing to attack Alexandropol, and the 18-strong Ardahan Corps was preparing to attack Akhaltsikhe and Tiflis.

Grand Duke Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov. Hood. E. Botman

The outbreak of war

The outbreak of war led to the fact that the Russian coast of the Caucasus was under threat.

Russian outposts located along the eastern coast of the Black Sea from the post of St. Nicholas (near the Turkish border) to Poti and the village of Redoubt were poorly fortified and had negligible forces. Their disunity and the lack of land communications through which reinforcements could be transferred made their defense pointless.

However, they did not want to leave them. The Redoubt contained a significant depot of artillery supplies and was guarded by only one company of soldiers. There were only a few dozen people in Poti, although there were two stone and well-preserved fortresses. At St. Nicholas Post (St. Nicholas Pier) there was a large food warehouse, and the garrison initially numbered several dozen soldiers. It was impossible to defend the posts with such forces, and even without coastal artillery.

Vorontsov persistently demanded from the high command of the troops. He believed that with the outbreak of war, an Anglo-French fleet would appear in the Black Sea, and this would be a disaster for the Caucasian coast. There were alarming news about the concentration of Ottoman troops on the border in Batumi. Vorontsov asked Menshikov to strengthen the Russian squadron cruising off the Caucasian coast. However, Menshikov’s instructions to the chief of staff of the Black Sea fleet Kornilov on October 10, 1853 about the need to increase vigilance was belated.

The first enemy attack was taken by the garrison of the post of St. Nicholas.

It was a common border post (border outpost) for the Caucasus, consisting of several dozen small wooden houses on the Black Sea shore. The head of the post, officials of the quarantine and customs service, soldiers, and local residents lived here. At the post there was a store (warehouse) with provisions and several merchant shops for trading with surrounding villages. There were no fortifications, nor artillery.

At the post they discovered military preparations in the Turkish border area. Alarming news from Batumi was brought by the Adjarians, who were friendly towards the Russians.

The head of the St. Nicholas post, infantry captain Shcherbakov, sent more than one alarming message to his superior, Prince Andronikov, in Akhaltsykh. Several Ottoman “camps” (infantry formations) were brought by sea to Batumi. The Ottomans secretly installed several artillery batteries on the border (they worked at night to conceal military preparations).

In Batumi Bay there was a concentration of Ottoman ships - feluccas, on which troops were transported along the coast. Each ship could have several falconets on board and could transport several dozen soldiers. Many ships came from the Mediterranean, which attracted the attention of local residents.

The command of the Gurian Military District informed Vorontsov about this. At the insistence of Andronikov, although there were not enough troops, they decided to strengthen the post. Two incomplete companies from the Black Sea linear battalion (255 riflemen) with two field guns, several mounted Kuban Cossacks for reconnaissance and delivery of reports, as well as two hundred foot Gurian militia (local volunteers) under the command of Prince George Gurieli arrived at the outpost.

Vorontsov, in a letter to Emperor Nicholas, noted the high fighting qualities of the Gurian militias:

Having received solid reinforcements, Captain Shcherbakov and Prince Gurieli began strengthening the defense in the entrusted area. Patrols were posted on the mountain paths near the border. Each platoon of riflemen and a hundred militia distributed their areas for defense. Captain Shcherbakov had orders to hold his post until the provisions were removed from the local store.

The Ottoman commander-in-chief and commander of the Anatolian army, Abdi Pasha, received a secret order from Constantinople to begin hostilities even before the official declaration of the “holy war.” The Anatolian army targeted Alexandropol and Akhaltsy, the Turks and their English and French advisers planned to unite the army with the Shamil highlanders, cause a widespread uprising in the Caucasus against the Russian authorities and destroy the cut-off Russian army in Transcaucasia. Then it was possible to transfer the fighting to the North Caucasus.

The Primorsky direction was auxiliary. The landing force was supposed to capture the St. Nicholas post with a surprise attack. They wanted to completely destroy the Russian garrison so that no one could warn the Russian command about the start of the war.

This ensured the further success of the offensive of the Ottoman troops. After capturing the post, Turkish troops were supposed to occupy Guria, from where the road to the cities of Kutais and Tiflis opened.

Death of the post of St. Nicholas

On the night of October 16 (28), 1853, a large Turkish landing force - about 5 thousand people - was landed in the area of the St. Nicholas post. The Ottomans had a more than tenfold advantage in manpower. The Turks landed at the mouth of the Natamba River, three kilometers north of the post. And this transfer went unnoticed by the Russian garrison. The enemy invasion was expected from Batum, and not from the sea. Ottoman soldiers began to surround the post, hiding in the forest. Falconets with feluccas and small cannons were placed in positions.

The Ottomans were able to attack suddenly. The assault on the post began with heavy artillery fire. A barrage of fire fell on the sleeping garrison. Sleepy soldiers, border guards and Gurian militias dismantled weapon and took their positions.

The two-gun battery returned fire. After the artillery shelling, numerous Ottoman infantry rushed to the attack, wanting to crush the small garrison of the Russian post with one blow. The main blow came from the rear.

However, despite the surprise attack and overwhelming superiority in numbers, the garrison repelled the first assault. First, gun salvos thundered, then the soldiers opened rapid fire, the artillerymen mowed down the opponents with grapeshot, who tried to rush into the post in large crowds and suppress the defenders in hand-to-hand combat.

The Turks met with unexpectedly violent resistance, suffered heavy losses and retreated.

The battle dragged on. The first attack was followed by new ones, no less persistent and massive. Captain Shcherbakov, after repelling the first blow, sent messengers to the headquarters of the Gurian detachment and to General Andronikov in Akhaltsykh. Under cover of darkness, the Cossacks managed to get through a chain of enemy posts and disappeared into the forest.

As a result of a surprise attack, the Turkish army did not succeed in the coastal direction.

The garrison continued desperate resistance and was completely surrounded. At first, the Turkish attacks were repelled by rifle and cannon fire, but by morning the ammunition ran out. The enemy had to be met with the chest and repelled with bayonet blows. Prince Gurieli was wounded, but continued to lead the militia. When he was struck down by a Turkish bullet, the Gurian warriors were led by his son Joseph. He also fell in this battle.

The remnants of the garrison, seeing that the post could no longer be defended, went for a breakthrough. Before that, they burned down a store with provisions. Russian soldiers made their way with bayonets, the Gurians cut down the enemy with sabers.

A desperate counterattack by the fighters of the Black Sea linear battalion No. 12 and the Gurian militia saved the last fighters. Brave warriors made their way into the forest, and the Ottomans did not dare to pursue them.

Only three officers (they were badly wounded), 24 riflemen and a handful of Gurian policemen were able to break out of the encirclement.

Most of the garrison of the post of St. Nicholas died the death of the brave. Captain Shcherbakov died, princes Gurieli - father and son, almost two hundred Gurian militias, most of the Russian riflemen - died.

The Russian-Gurian detachment died with glory and honor in an unequal battle and completed its task. The Ottomans failed to launch a surprise attack on the coastal flank. The Turkish army lost the element of surprise.

The Bashi-bazouks (“thugs, reckless”, irregular units in the Ottoman army) at the post of St. Nicholas committed one of the war crimes with which the Turkish army marked its path.

Menshikov reported to Grand Duke Constantine:

The Russian command sent a detachment of three companies of the Lithuanian Jaeger Regiment, one platoon of the Black Sea 12th battalion and hundreds of Gurian militia, with two guns under the command of Colonel Karganov, to help the post garrison.

During the march, news arrived about the fall of the post, the troops accelerated their movement and immediately attacked the Turkish army, which was holed up behind forest rubble two miles from the post of St. Nicholas. Russian troops captured enemy positions, but, having discovered a large enemy detachment, turned back.

The European press greatly exaggerated the strategic significance of the fall of the post of St. Nicholas. This local success of the Turkish army did not influence the development of the war. The Turkish army could not advance along the coast; there were no roads. But a surprise attack on Guria and a further breakthrough to Kutaisi did not work out.

Information