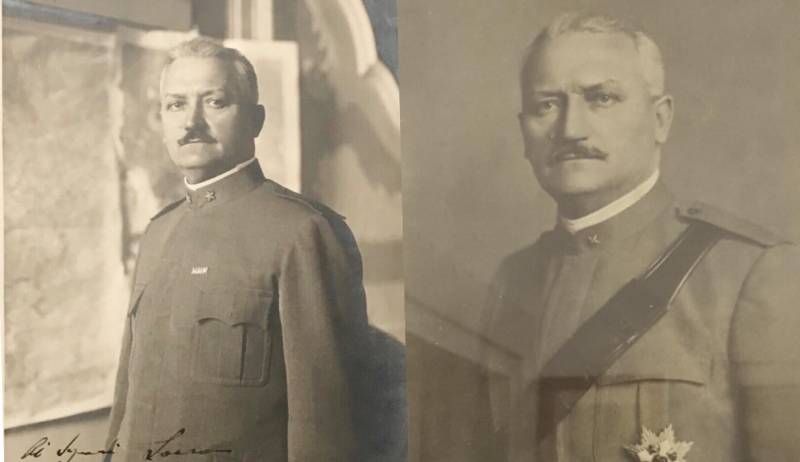

The Forgotten Hero of the First World War: The Life and Career of Marshal of Italy Enrico Cavigli

The name of Marshal of Italy Enrico Cavigli is poorly known not only to the Russian reader, but also to a significant part of Italians - many Italian historians note: despite the fact that he was one of the most capable generals of the First World War, today most Italians know almost nothing about him. Unlike the same “Duke of Victory” Armando Diaz, well known and recognizable in Italy, Caviglia was forgotten by both politicians and historians.

If we talk about the historiography of the First World War in general, then, as correctly noted in the preface of the second volume of I generali italiani della Grande Guerra ("Italian Generals of the Great War") by historians Paolo Gaspari and Paolo Pozzato, studies regarding the role of Italian generals who participated in the war often suffered from certain ideological prejudices, far from the strict methodology of the historian [2].

Attempts to judge the past through the eyes of the present led to the fact that Italian patriotism and irredentism (many Italians went to Italy to fight as volunteers from territories that once belonged to Italy and were claimed by Italian nationalists) after World War II began to be associated with the “forerunner of fascism.” . The Italian generals of the Great War also began to be viewed from a corresponding angle.

Additionally, the image of senior World War I officers is often that of incompetent men with no respect for the lives of their subordinates, convinced that they were mere "cannon fodder"; all this, of course, occurs in the context of negative attitudes towards Italian intervention in the war.

This is not to say that this image is completely untrue - in fact, the Italian military command was full of incompetent generals who senselessly threw soldiers into frontal attacks (for example, Luigi Cadorna). However, firstly, some generals learned from their mistakes and tried to introduce innovations dictated by the times, and secondly, it should be taken into account that all the armies participating in the war and their leadership were faced with a new type of war, to which they were not ready.

The modernity of the First World War lay not so much in the strategies used, but in the use of all those discoveries that were made by science at the end of the XNUMXth and beginning of the XNUMXth centuries: chemical weapon, airplanes, Tanks, machine guns, heavy artillery. It was a high-tech war that could not be compared with the wars of the past, which people at the turn of the century should have understood [2].

The hero of this article, Enrico Caviglia, was precisely the general who tried to understand the war, did not act in patterns and criticized the ineffective methods of military command.

Failed sailor: the beginning of Enrico Cavigli's military career

Enrico Caviglia was born on March 4, 1862 in Finalmarina in the province of Savona into a family of middle-class sailors and merchants Pietro and Antonina Saccone [1]. His father was confident that his son would become a sailor, perhaps the captain of a merchant ship. Enrico loved the sea, and he would retain this love and good relations with the sailors of his hometown for the rest of his life, but he had only one dream: he wanted to be a soldier [3].

At fifteen he left his family and entered a military school in Milan, and then became a cadet at the Military Academy in Turin. On August 25, 1885, he was promoted to lieutenant.

In October 1888, he asked to serve in the Royal Italian Colonial Army in Eritrea. In Africa, as commander of an artillery battery, he participated in various expeditions. Returning to Italy, he attended the Military School and was then selected to attend the General Staff School. In this regard, Caviglia decided to leave the artillery and become a staff officer. However, he was sent back to Africa, where on March 1, 1896, he participated in the Battle of Adwa, the largest Italian defeat in Africa.[3]

In 1901 he was promoted to major, and the following year he was appointed military attaché extraordinary in Tokyo, where he was tasked with monitoring developments during the Russo-Japanese War in Manchuria. From 1905 to 1911, Caviglia was military attaché in Tokyo and Beijing.[1]

This mission was important for the future Italian general, not only because he could travel, which was one of his desires, but also because, by observing and studying the Russo-Japanese War, he was able to understand some of the tactics used by the Japanese in the Battle of Yalu River [3]. This knowledge was later useful in the battles of Bainsiz and Piave.

After a short stay in Africa in 1912, Caviglia worked for some time in Italy at the Geographical Military Institute, and on February 1, 1914 he was promoted to colonel. A few months later, on July 28, 1914, World War I began.

General Caviglia on the fields of the First World War

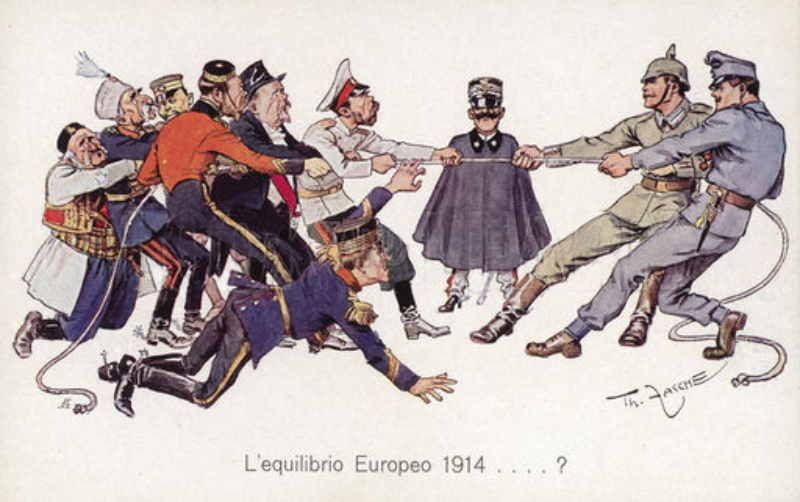

Caricature on the theme of Italian neutrality - Victor Emmanuel in the center oversees the tug-of-war between the Central Powers on the right and the Entente countries on the left.

Despite the fact that Italy entered into an alliance treaty with Berlin and Vienna, at the beginning of the war the country's leadership decided to remain neutral, using one of the articles of the treaty. When it became clear that the war would continue for a long time and would not be completed in a few months, Germany and Austria-Hungary on the one hand, France, Great Britain and Russia on the other tried to convince Italy to enter the conflict on their side.

The German Empire also offered Italy to remain neutral, giving up some Italian regions that were under the control of Austria-Hungary as a reward. Of course, the Austrian government opposed this proposal and stated that it was only ready to discuss minor changes in borders [3]. As a result, Rome decided to enter the war on the side of the Entente, signing a secret treaty in London.

At the start of the war against Austria-Hungary, Italy had the advantage, but two serious mistakes were made: the Italian General Staff was confident that the Austrian defenses were strong in Trentino and that there were enough Austrian troops in Friuli to stop the Regio Esercito (Royal Italian Army), so the advance was too slow.

In addition, the Italian forces did not advance in the strongest way in Trentino, since it was one of the most important railway junctions between Austria and Germany, and the Italian government was afraid of a German reaction. Therefore, military operations were concentrated along the Isonzo line, which was partly in accordance with Allied advice [3].

Almost immediately after the start of the war, Enrico Caviglia was sent to the front line and received the rank of brigadier general. In the summer of 1915, he took command of the Bari brigade, which took part in the battles of Bosco Lancia and Bosco Cappuccio. Thus began his rapid ascent to high command, which he accomplished exclusively at the head of front-line units, and not in the safe offices of the General Staff [1].

The war in Italy was extremely difficult, because it was complicated by geographical conditions. Many battles were fought in the mountains (sometimes at an altitude of more than 2 m above sea level), and at times it was even impossible to dig trenches to protect the soldiers. Enrico Caviglia was very critical of the tactics and strategy of Luigi Cadorna, commander-in-chief of the Royal Italian Army, and expressed all his ideas to the command, but they were not listened to, and the general obeyed orders obliging the troops to attack the trenches head-on [000].

Italian soldiers on the difficult front in the Alps in 1916

– Caviglia wrote in his diary.

He noted that he was forced to obey the command and had no opportunity to prevent frontal assaults and casualties among soldiers.

During the reorganization of the army in the spring of 1916, Caviglia was given command of the 29th Division, with which he went to the Isonzo front in June to help stop the Austrian advance from Trentino. The Austrians were close to breaking the resistance of the Italians, and in this they were partly helped by General Cadorna, who was confident that this offensive was just a diversionary maneuver, and therefore there was no need to send reserves to this area.

An Italian 75 mm anti-aircraft gun in action during the 11th Battle of the Isonzo.

For his actions, Caviglia was awarded a knighthood in the Military Order of Savoy. He remained on the Asiago plateau until June 1917, also participating in the Battle of Ortigar, the approach of which he strongly criticized.[1]

In his memoirs, Caviglia wrote that all Italian tactics during this period were so predictable that the Austrians knew every time where the enemy’s attack would be, being ready to repel it [3].

In July 1917, Caviglia was given command of the XXIV Army Corps, deployed along the Soča River, which, with the 47th and 60th divisions, was to cross the river and penetrate the Bainsizza plateau as part of the so-called 11th Battle of Soča.

Careful preparation and the use of surprise allowed the XXIV Corps to cross the river on the morning of August 19 with part of the troops, and then, after a flanking maneuver that crushed the Austrian defenses, on August 20 with the remaining forces to begin a rapid penetration into the interior of the country. However, the lack of fresh reserves (the command did not expect such obvious success) did not allow strategic use of this advantage [1].

On October 24, 1917, the great Austro-German offensive slightly affected Caviglia's troops, who easily repelled the attacks. In the evening of the same day, the command of the 2nd Army placed Caviglia at the head of the three surviving divisions of P. Badoglio and ordered him to begin a retreat from Bainsizza. During the retreat, Caviglia managed to retain the bulk of his troops [1].

On November 22, during the reorganization of the army, the XXIV Corps was disbanded. This measure was perceived by Enrico Caviglia as revenge from P. Badoglio, who, taking advantage of his appointment to the post of Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Army, wanted to preserve his defeated and disbanded XXVII Corps, sacrificing instead the XXIV Corps, which absorbed his forces. This episode intensified the rivalry between the two generals, which was to have more serious consequences in subsequent years.[1]

Enrico Cavigli's contribution to the victory under Vittorio Veneto

The Italian army was defeated at Caporetto not only due to the presence of assault troops, the use of new tactics and the massive use of poison gases, but also due to an incorrect strategic approach. The Italian General Staff was confident that an offensive was impossible, so the entire Italian deployment was offensive, and the defenses were not prepared to repel a strong attack [3].

The German offensive was almost perfect, led by highly professional officers (one of them was Erwin Rommel). Of course, surprise had an effect, but the ineffectiveness of the Italian generals greatly helped the enemy [3].

After this, Luigi Cadorna was removed from his post as Chief of the General Staff, and Armando Diaz took his place. Soon after, Díaz handed over command of the 8th Army to Caviglia.

By that time, the crisis of the Central Powers had become obvious, and the Italian government, which until then had advocated total defense, began to ask General A. Diaz to carry out a decisive offensive before the onset of winter.

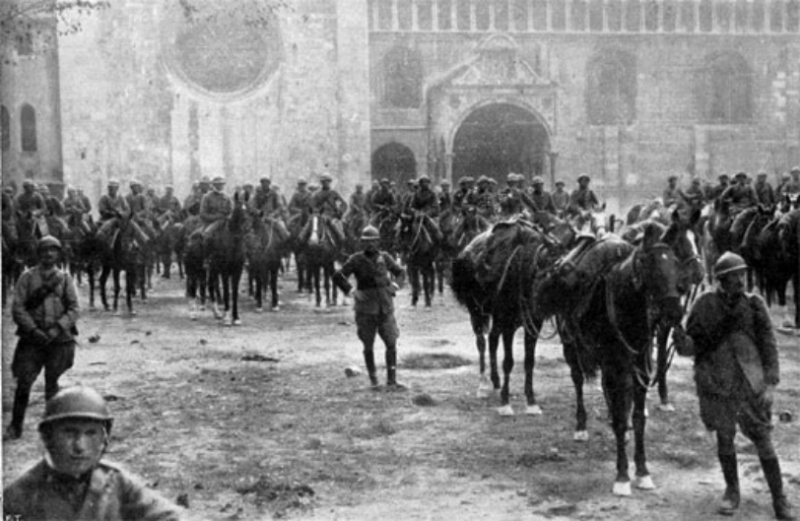

Italian cavalry enters Trento on November 3, 1918

At the end of September, the head of the operational department of the High Command, Colonel U. Cavaliero, developed an offensive plan for the 8th Army of Diaz and Badoglio. Caviglia approved it, but asked and obtained an extension of the offensive front to the Vidora bridges in the north and Grave di Papadopoli in the south, in order to take advantage of the expected superiority of forces [1].

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto began on 24 October 1919 with unsuccessful attacks by the 4th Army on Grappa. Due to the flooding of the Piave River, the construction of bridges had to be postponed until the night of October 26-27. Caviglia transferred his reserves to the south, forced them to cross the Grave di Papadopoli bridges and rise to the north on the 28th, which led to the collapse of the Austrian defense - it was the threat of an attack on the flank that became one of the reasons for the withdrawal of the Austro-Hungarian army.

On October 29, the 8th Army crossed the Piave River and made a strategic breakthrough, which was facilitated by the moral and political crisis of the Austro-Hungarian units. On the same day, the enemy command asked to begin negotiations on surrender [1].

After the war, Caviglia received various honors and titles - in particular, he was appointed senator by the king. In the army he received the nickname “general of victory.” In 1926 he became Marshal of Italy.

However, Caviglia found himself deeply in the shadow of the “Duke of Victory” Armando Diaz and his deputy Pietro Badoglio.

General taking responsibility for unpopular decisions

After the end of the war in Italy, the issue of demobilization became acute - there were about 3,7 million soldiers in the army (not counting officers), and the problem was how to organize the return of these people home. The Minister of War Vittorio Italico Zupelli was unable to cope with the situation, for this reason Caviglia was appointed Minister of War, tasked with developing a demobilization program balanced with the needs of politics, the economy and the war-weary population [1].

As Minister of War (he held it from January 18 to June 23, 1919), Enrico Caviglia tried to stop the struggle between socialists and former soldiers close to the new movements that would later unite into the fascist party [3]. Caviglia skillfully promoted measures taken in favor of the demobilized, and took an active interest in additional officers, to whom he granted privileges [1].

At the end of 1919, without government permission, Gabriele D'Annunzio, dissatisfied with the peace treaty, occupied the city of Fiume with volunteers (some of them active Italian soldiers) and proclaimed the Republic of Fiume. This military action went beyond the territorial concessions provided for in the peace treaty. To avoid an international crisis, the army was tasked with occupying the city [3].

The sector commander was Badoglio, but he knew that D'Annunzio had the support of Italian public opinion, and therefore proposed that command be transferred to Caviglie, who was not known to be politically engaged. Moreover, Badoglio knew that whoever defeated D'Annunzio and his legionnaires would be hated by all Italian veterans and a large part of the Italian people. Indeed, this is what happened. But Caviglia was a soldier, so he did it without thinking about the consequences [3].

Subsequently, on July 17, 1921, Caviglia declared in the Senate that he opposed D'Annunzio only because the government had deceived him regarding the real extent of territorial concessions to Yugoslavia, and admitted that instead of a profitable agreement he had brought an “asp” to Fiume. This was too abrupt a change of position to inspire confidence, and as a result Caviglia found himself isolated [1].

From 1921 to 1925, appointed commander of one of the four armies and a member of the Military Council (or Council of the Army, the body that at that time represented the top decision-making body of the military apparatus), Caviglia occupied a leading position in Italian military policy. However, he did not actively participate in the debate on the reorganization of the armed forces, adhering to the position of A. Diaz and G. Giardino, supporters of a return to pre-war structures [1].

In the first months of 1925, Caviglia supported the campaign that Giardino, with the consent of most of the famous generals, launched against the army reorganization project carried out by the Minister of War, General A. Di Giorgio. The campaign culminated in a loud debate in the Senate, where the determined opposition of all the "generals of victory" prompted Benito Mussolini to abandon Di Giorgio and personally head the War Ministry [1].

To clearly demonstrate the regime's interest in the military and at the same time undermine the position of the generals who challenged him, Mussolini resorted to the help of Badoglio, the only of the great generals who did not take part in the dispute. He then appointed him Chief of the General Staff with greater powers than before to control the army.

Caviglia opposed this and expressed extremely harsh judgments about his colleague, and also spread too bitter and persistent accusations against Badoglio, which was perceived as the result of personal hostility (and partly this was true). Mussolini did not take this criticism into account and gave Badoglio the green light to remove his rival from all senior positions in the army.

The last years of General E. Caviglia

Subsequently, in his memoirs, Caviglia repeatedly subjected Badoglio to harsh criticism. In particular, in the book La dodicesima battaglia: Caporetto (“Collection of stories First World War" edited by General A. Gatti), which was published in 1933, along with judgments about the valor of the troops and polemics with the official version, which blamed the defeat on the soldiers and defeatism, a polemic with Badoglio, implicitly presented as the culprit, developed defeats.

A passage of a few pages about Badoglio's career, in which personal animosity led Caviglia to freely interpret the facts, was not included in the edition of the volume, but was sent to the king and Mussolini and circulated in circles hostile to Badoglio, who did not consider it necessary to respond to this criticism [1 ].

Enrico Caviglia was quite critical of Italy's entry into World War II, but had no influence on the situation. After the heavy defeats of 1942–1943, he naively hoped that the Anglo-Americans and Germans would agree to Italy's withdrawal from the conflict and its neutralization.

In 1943, when Italy was partially captured by Allied troops and it became clear that there was no way to resist, the secret government led by Pietro Badoglio, after Mussolini was removed from power, made contacts with the Americans and the British to get Italy out of the war [3].

However, the capitulation of Italy was unsuccessful, since the orders to the troops were contradictory, and there were many German divisions in the country. Therefore, on the day of the announcement of surrender, the king and his family, some of the generals, ministers and Badoglio left Rome, leaving the troops without orders and commanders [3].

Caviglia, a retired general, was in Rome at that time - in his diary he wrote that he was there supposedly on personal business (in fact, he probably met with the king the day before). Finding himself in the capital without leadership, already under attack by Albert Kesselring's divisions, old Caviglia (81 years old at the time) began giving orders for defense.

However, he understood that demoralized troops could not resist, and that this could not be done without serious damage to the city and large losses among the civilian population, so he decided to negotiate with the Germans, saving the city from a harsh air raid [3].

After this, without receiving any gratitude from either the city or the king, he took the train and returned to his home in Finale Ligure. He spent the last two years of his life in his hometown.

Enrico Caviglia died on March 22, 1945. About ten days earlier, he suffered a stroke [4].

Mausoleum of General Enrico Cavigli

On June 22, 1952, Caviglia's body, resting in the family crypt, was solemnly transferred to the mausoleum in the old watchtower above Finale Ligure. The ceremony was attended by the President of the Italian Republic Luigi Einaudi, V. E. Orlando, members of parliament, government officials, representatives of civil, military and religious authorities, as well as veterans of the Great War, its soldiers who arrived from all over Italy [4].

Использованная литература:

[1]. Giorgio Rochat. Caviglia Enrico, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 23, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

[2]. Paolo Gaspari, Paolo Pozzato. I generali italiani della Grande guerra, atlante biografico. Volume II, CZ. Udine: Gaspari Editore, 2019.

[3]. Innocenti, G., Enrico Caviglia – the forgotten Italian. A Life as Soldier, Writer, serving the country, in ACTA, 2014. World War One 1914–1918, Urch Alma Mater “St. Kliment Ohridski” University Press, Sofia, Bulgaria 2015: 393–409.

[4]. Pier Paolo Cervon. Enrico Caviglia protagonista della prima Guerra mondiale, “generale della vittoria” // Pubblicato in Quaderni savonesi n. 9, 2008.

Information