About Russians and Slavs from the perspective of ancient history

“...This war, however, did not remain without truly beneficial consequences. She showed us that it was not any European party that hated us, but, on the contrary, that, whatever the interests that divide Europe, they are all united in a common hostile feeling towards Russia... That common (absorbing all differences of parties and interests) hatred of Russia, which Europe revealed in word and deed, has finally begun to open our eyes.” (N. Ya. Danilevsky, 1871).

foreword

Superficial knowledge stories of one’s own country, coupled with its constant rewriting (reinterpretation) to suit the interests of the ruling elite, has been a traditional feature of our society since the time of Rurik Rostislavich. Therefore, most people, not having true knowledge of history, perceive the events currently taking place in the country with surprise, although their occurrence is quite logical and can easily be explained (and predictable) with the help of historical knowledge, because history tends to repeat itself.

The current critical state of relations between the states of the Russian Federation and Ukraine, considered (and indeed were) before the collapse of the USSR fraternal republics of the RSFSR and Ukrainian SSR, causes many people who proudly call themselves Soviet officers acute pain and a strong need to speak out - to publicly express their attitude to reality.

I have no desire to discuss the military and political components of the speeches of those speaking out, but I want to try to highlight another important aspect of their speeches, namely the question of who is fighting with whom: Russians with Russians; Russians with Ukrainians; Ukrainians and Muscovites? And other verbal options that describe reality from the perspective of graduates of the same military schools, who now find themselves on opposite sides of the front line.

I will immediately note that the names of nationalities I cited above have now almost completely lost their original historical meaning, and the dispute regarding their true meaning represents a debate about the correct interpretation of various literary (and folk) words and expressions. That is, a conversation about the correctness of various conventions.

Unfortunately, people at all times have neglected not only the study of the history of their country and their own nationality, but even the understanding of their own life experience.

And the efforts of many Russian philosophers and historians, who repeatedly pointed out the importance of knowledge and understanding of history for subsequent generations, were in vain:

“History is the result of human experience; We can forget experiences only when we no longer need them, meanwhile, even now, at every step we come across facts that are incomprehensible to us from a modern point of view, but can only be explained by history” (E.P. Savelyev, beginning of the XNUMXth century).

Unfortunately, these wise sayings went unnoticed and did not take root in the minds of subsequent generations; descendants could not or did not want to understand the lessons of history. And now, when conducting combat operations, we are stepping on the same rake that not only our great-grandfathers or great-great-grandfathers stepped on, but also our grandfathers, fathers, and ourselves (if you remember Afghanistan or two Chechen ones).

Over the past 15 years, I have devoted a lot of time to studying the history of the Great Patriotic War. And now, comparing the events taking place on the fronts with what happened then, I am once again convinced of the correctness of my conclusion: those who know the past well have the opportunity to predict the future with acceptable accuracy, because the future is the logical conclusion of the past, and sometimes even its almost complete repetition.

And vice versa: those who do not know their past usually greet the present with great surprise.

Comrade officers, I apologize, in the heat of my speech I deviated from the topic that I intended to cover for you.

So.

Who are the Rus, Slavs and what is Kievan Rus?

After listening to the video speeches of some of our honored officers, I noticed that many speakers do not know well enough the true meaning of the historical terms given in the title of this section. But they are happy to use them in their speeches and journalism.

And there is nothing shameful here, because even most professional historians are ignorant on this issue.

I am telling you top secret (in the world of historians) information: a real historian knows perfectly only some narrow historical question, for example, what were the funeral customs of the ancient Slavs living in Novgorod and its environs in the 1941th–XNUMXth centuries. And in some other narrow historical question (for example, how the battles near Volokolamsk and Istra actually took place in the second half of November XNUMX), this historian will be competent to the same extent as an ordinary person using easily accessible (and sometimes very dubious) sources .

I return to the question I outlined in the section title.

Let me make a reservation right away: there is no generally accepted (considered by everyone to be correct) answer to these questions, as they say in such cases: regarding the named concepts (terms), historians have separate opinions, which often do not coincide with each other.

Or to put it another way: these questions are debatable, because due to the scarcity of ancient historical documents, they move from a purely historical plane to an ethnological and even philosophical plane.

And, as I noted above, discussions often descend into disputes about the correct interpretation of the meanings of individual words or phrases used by historians as terms.

Therefore, I do not insist on accepting what is stated below as the absolute truth, but I would like to note that the information I have provided is not a figment of my imagination - at the end of the essay I will indicate a list of historical works that I used.

On the origin of the words “Russian” and “Slav”

On the long path of development of earthly civilization, there was no other people who would have left their mark on history under so many names (certainly more than fifty). How did this happen?

The explanation is simple. Any people always goes down in history under two types of names:

1) by which he calls himself;

2) which are assigned to him by the surrounding peoples (with whom he fights, or neighbors or trades), usually choosing a nickname for him from their own language.

Our ancestors called themselves two names: Russ (Rusin) and Slav.

Which of the names is more ancient and how did they arise?

Russ

According to some Russian historians of the XNUMXth century, “Rossy” and “Russy” are the most ancient generic name of all Russian tribes.

In various eras, the Russians appeared on the historical stage under numerous names, for example: Veneds, Scythians, Massagetae, Antes, Agofirs, Sarmatians, Saki, Skolots, Getae, Alans, Roksolans, Budins, Yaksamatas, Trojans, Rugs, Ruzhans (Russian farmers) . All these names were given by the surrounding peoples to numerous Russian tribes living in various eras in vast territories from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and from the Caspian Sea to Central Asia and the Middle East, and even to Egypt.

Our ancestors themselves usually called themselves by their own names: Rossy, Russy, Rose, Ruzy, Resy, Ras, Rsi, Rsa, Rsha, Race, Rosha, Razy, Razen, Roksy. Or sometimes complex, for example, Aorsi or Etruscans (Getruscans).

There is a version that the name “Ross” is formed from the word “rsa” - water, river. Other ancient words related to water are derived from it: “dew”, “mermaid” and “bed”. Our ancestors always tried to establish their settlements near rivers or lakes. Which is easily explained: rivers were not only natural reserves of water and food (fish and waterfowl).

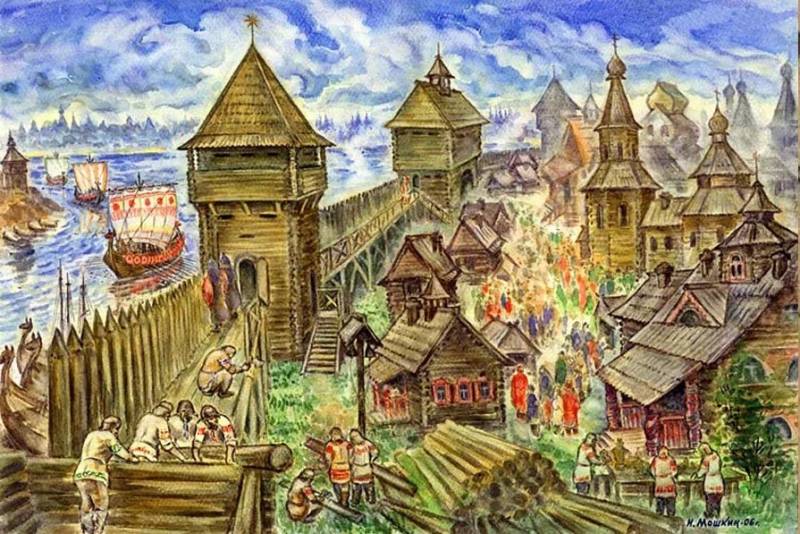

In ancient times, they also served as natural transport arteries connecting Russian settlements widely scattered across the continent. Even in the XNUMXth–XNUMXth centuries, the territory inhabited by Russian tribes, stretching from Novgorod to Kiev, was still dense impenetrable forests and swamps, and it was possible to get from settlement to settlement only by moving along the rivers: in the summer by boats, and in the winter by sleigh.

It was for these reasons that the ancient Russians settled near rivers. In many places where they once lived, the ancient names of rivers have been preserved to this day: Rsa, Rusa, Ruza, Rusyanka, as well as the names of ancient towns - Russa, Rusa and Ruza.

According to another version, on the contrary, the word “rsa” - water, was derived from the generic name of the ethnic group - “Ross”.

It is difficult to judge which version is correct (or both are incorrect): the deeper you plunge into the mists of centuries, the more guesswork your assumptions become and the more disputes arise between supporters of various “historical schools”.

There is another version.

There is a legend that about 4 years ago in the high part of Asia on the southern slope of the Indukush mountain range lived the highly civilized people of Parsi (Po-Rsy), who gave the so-called “displacements” from their composition - tribes that settled Europe, uninhabited at that time, Asia, and even part of Africa. It is possible that the ancient name “Rsy” is precisely the source from which the name Russy emerged many centuries later. And it served as the root for the production of the words dew and mermaid.

It is well known that the living folk language is not characterized by stagnation; it constantly changes its forms, words lengthen, and sometimes vowels are replaced. However, the most ancient roots, which serve as the framework of words, live unchanged for thousands of years.

For example, in addition to the word “rsa”, we can cite other words of the Old Russian language, which were used by our ancestors 2500 years ago almost exactly in the same form as now: honey, will, evening, nocho (night), door, sky, sweetheart (me), home, trouble, child or child, daughter, brother and many others.

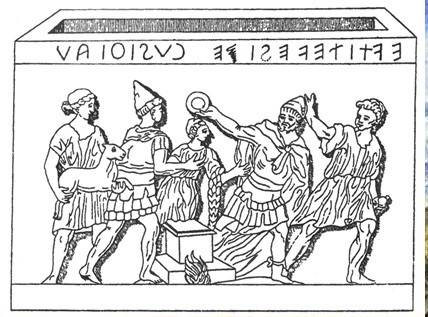

Some Old Russian gravestone inscriptions are made from right to left, which was later adopted by the Arabs. Once in the XNUMXth century, an ancient sarcophagus was found in Italy. Historians from all over the world tried unsuccessfully to guess what kind of ritual was depicted here, and struggled for a long time to decipher the inscription, but they were never able to unravel it. Unexpectedly for everyone, the little-known amateur philologist F. Volansky was able to comprehend this historical secret.

He read and translated the inscription using the Old Russian language: EVTITE BESI HER KUSITALE - “appear the demons, her tempters.” It was learned that the scene depicts the exorcism of demons by sorcerers from a woman possessed by them. The inscription is made from right to left, and now, knowing the answer, even you and I can clearly make out the first word EVTITE:

And on one gravestone, more than 2000 years old, F. Volansky discovered an inscription that seemed to be written in melodious Ukrainian: “Mila Lale, my beauty.” Which once again proves: the Russian language has not changed at all as quickly and dramatically as we are accustomed to believe.

Or let’s take, for example, the name of the first Russian prince mentioned in Greek chronographs - Oleg. At a superficial glance, it seems to us somehow incomprehensible, perhaps even foreign.

And the answer is on the surface: the name Oleg is derived from the ancient Russian word “will” (vlya), and it once sounded like Voleg, which means freedom-loving, not tolerating domination over oneself. Then, due to the habit inherent in the living folk dialect of abbreviating some words by subtracting the first letters, “v” disappeared, and it turned out Oleg.

Moreover, the name Voleg also had a feminine gender: Volga - Olga - Olga. You see, how interesting it is, well, which of you, without my prompting, would have been able to figure out that the name Olga is nothing more than a shortened name of the great Russian river?

Or let’s take a softened folk version of this name - Olya, which is nothing more than an abbreviation of the same word “will”, which gave birth to a large number of other words: “volunteer”; "slave"; “volode” (to own), which gave the origin to another name - Volodymyr (who owns the world); “Volodyko” (lord); "possession" (possession). And also the word “volost”, from which the word “power” later came. The word “will” can also be found in the names of old Russian cities: Volyn and its Ukrainian version Vilno(e).

The above suggests that the call for independence, put into words by our ancestors many centuries ago, has not gone away, has not sunk into oblivion, has not disappeared into the mists of time. It secretly accompanies us to this day, and if you listen very carefully, you will definitely catch its proud sound, muted over millennia.

Many Russian settlements in present-day Europe are very ancient. For example, according to the Russian historian of the 2000th century E.I. Klassen, the Wends (considered by him one of the Russian-Slavic tribes) were in the Baltic Sea region XNUMX years BC, and already at that time they had their own written language. The Alexandrian scientist Ptolemy left information that in the second century AD there was a country called Great Russia.

Here I would like to note that the name Rus, as an ethnographic term, had a very flexible character. In a broad (pan-European) sense, it meant all the Eastern Slavs, subject to the Russian princes; in a less extensive sense, it meant the South Russian Slavs; in a narrow sense, it meant the Polyan tribe or Kievan Rus itself. Finally, sometimes the meaning of this name was narrowed to the concept of class - that was the name of the squad of the Kyiv prince.

Slavs

Some historians believed that the Russians themselves came up with this name, and they liked to call themselves that during various solemn and official relations with other peoples. Allegedly, this name is derived from “glory,” for the ancient Russians were an extremely warlike and very proud people, who believed that in numerous battles they covered themselves with great glory, for which their enemies should respect and fear them.

They often derived their names from the word “glory,” for example: Vladislav, Yaroslav, Svyatoslav, Boguslav, Dobroslav, Bretislav, Bureslav, Mecheslav, Miroslav.

Over the course of centuries, the name “Slavs” began to gradually replace the generic name “Russians,” and by the end of the first millennium AD, some Russian tribes already called themselves not Russians, but rather Slavs, such as the tribes living in Novgorod and its environs.

And those who lived in Kyiv and its environs, on the contrary, did not call themselves Slavs, and when asked “Who are you?” They answered: “I am a Rusyn.” Thus, at a certain stage in the development of a single people, two different nationalities arose: Rusyn and Slav.

It is also interesting to note that the name “Slavs” was most often used in Greek and Roman sources. But the Arabs preferred to call our ancestors Russians, and they still call our country “Russia” and people “Rus”.

There were also significant differences in the customs of the Slavs and the Russians. For example, the Slavs burned the dead, and the Russians gave them to the land, and in clothes and with weapons. Moreover, sometimes, so that the deceased would not get bored in the afterlife, his living wife was buried with him.

It is also curious that, according to foreign sources at the end of the first millennium, the Russians were a seafaring people and loved to make sea voyages (and robberies). The Slavs, on the contrary, were land warriors.

But the Russian historian D.I. Ilovaisky put forward a different version.

According to his assumption, the name Slavs did not come from fame at all, but is a modified name of the Russian tribe Saki, under which they were known to the ancient historian Herodotus (XNUMXth century BC). Then this word went through a series of transformations: Saki - Saklaby (among the Arabs) - Saklavy, Sklavy (among the Romans and Byzantines) - Slavy (the Slavs themselves remade the name Sklavy in their own way). It is known that the Romans and Byzantines long and stubbornly called the Russes Sclavs, and even called their slaves that way, apparently due to the fact that in ancient times they subjugated several Slavic tribes to their power (the word “slaves” was used in the meaning of “paying tribute”) .

The last version seems to me the most convincing, but now no one will tell how it really happened...

By the beginning of the XNUMXth century, the name “Slavs” had already become more widespread than “Russians.” Thus, as centuries passed, the names changed places: Russy became specific and now denotes a nationality, and Slavs became generic and denotes a set (genus) of nationalities, or in other words, a group of genetically related peoples living in various European countries.

For example, today Czechs, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Serbs and even Poles are called Slavs. But Russians are only residents of Russia, and even then not all of them.

Kievan Rus

Lately, I have often observed how various speakers and writers use this phrase in various variations, but at the same time they do not have the slightest idea of what it really means.

According to the assumptions of some Russian scientists who devoted their lives to studying the ancient history of their country, in the XNUMXth–XNUMXth centuries AD, on the territory of the Russian Empire there were three “bushes” of Russian tribes, to which historians assigned the code names “Azov-Black Sea Rus'”, “ Kievan Rus" and "Novgorod Rus".

Simply put, these names are not originally historical, but invented and introduced by scientists into scientific and historical circulation.

By Kievan Rus, historians meant the tribes that lived in Kiev and its environs (Polyana, Drevlyane, Radimichi, etc.), as well as those “sitting” at some distance from Kiev, but ultimately falling “under the arm” of the Kiev princes.

Some people consider Kievan Rus to be the oldest Russian state, which is completely wrong. Despite the fact that, according to the chronicles, the tribes living in the ancient “Kiev region” were tributaries of the Kiev princes, that is, they were formally under their authority, and in the wars started by the princes with neighboring peoples they were obliged to field a certain number of warriors, this commonwealth was called, involuntarily, semi-primitive tribes using the big word “state” would be sheer absurdity.

It is generally accepted that the Russian (Russian) state was founded at the end of the XNUMXth century by Moscow Prince Ivan III, and the name “Russia” itself was introduced into state documents by Ivan IV the Terrible in the second half of the XNUMXth century.

It can be concluded with some reservation that Kievan Rus (later transformed into the Principality of Kievan) finally ceased to exist at the beginning of the 1654th century after the Principality of Kievan became part of Lithuania. Kyiv was included in the Russian state only in XNUMX. And most of the territories that were once part of the principality were returned much later to the Russian Empire.

Thus, what is most curious and most certain is that the territory occupied by the modern state of Ukraine is historically Russian, and the city of Kyiv is the first Russian capital. For, as it is written in the ancient historical source The Tale of Bygone Years: “...And Oleg, the prince, sat down in Kyiv, and Oleg said: “Let this be the mother of Russian cities.”

According to one of the historical versions, the spread of Rus' went from the Kyiv lands to the north, and the Novgorod lands, where a democratic form of government (veche) previously existed, were the last to be included in its composition.

But these circumstances do not make the people now living on the historical territory of the Kyiv Principality Russian.

The issue of nationality is sometimes very ambiguous, and is often resolved not even “by blood”, but by the personal choice of a person in accordance with his own assessment of belonging to any nationality.

For example: one of my friends, born in the USSR, has an Uzbek father and a Ukrainian mother. Well, what do you think his nationality is? You guessed it - Russian.

Conclusion

Many centuries have passed since the departure of Kievan Rus into the historical darkness. Over the past centuries, on the vast territory of the former Principality of Kiev, which later became part of two empires (Russian and USSR), there has been an extensive migration of people, as well as the birth of many children who became the fruit of mixed marriages, when one of the parents was a representative of the indigenous population, and the other a person who arrived from another region of a huge country. And despite the fact that the former Ukrainian SSR has considerably “Russified” over the years of its existence, calling all people born and currently living in the territory of the state of Ukraine Russians, in my opinion, is not entirely correct.

It would be most correct to call them Slavs in the broad sense, and Ukrainians in the narrow sense (as they call themselves and as they were called during the USSR).

And now the war is not between Russians, and not even between Russians and Ukrainians. The war is being waged between Orthodox Slavs - this is the main tragedy of our days.

In terms of tragedy and fierceness, the ongoing hostilities can be compared with the Civil War in Russia that took place in the last century. Now people on both sides of the front (whose grandfathers and fathers were compatriots - citizens of the same country) are fighting to the death with tenacity and courage characteristic only of the Slavs. At the same time, everyone believes that the truth is on his side, and this confidence further intensifies mutual bitterness and embitterment. And their best fighting and moral-volitional qualities at the moment serve a negative goal - mutual destruction.

As has often happened in the history of our Motherland, the youngest and most courageous again die in a fratricidal war. And thousands of civilians die (again, Christian Slavs), who by misfortune find themselves in a combat zone...

And the worst thing is that there will be no winner in this war. With any development of events in historical terms, both opposing sides will be losers, and the gain in the form of the emergence of another century-long enmity between two fraternal Slavic peoples will go to the enemies of the Orthodox Slavic world...

And the emerging demographic vacuum will quickly be filled with immigrants from Central Asian countries; this trend is already noticeable in large Russian cities.

On this sad note, let me end this historical excursion (I admire those who had the patience to read to the end).

Bibliography:

Ilovaisky D.I. The Beginning of Rus'. Astrel, 2004 (based on materials from the 1890 publication).

Klasen E.I. New materials for the ancient history of the Slavs in general and the Slavic-Russians of the pre-Rurik period in particular with a light outline of the history of the Russians before the Nativity of Christ. M., Amrita-Rus, 2005 (based on materials from the 1854 publication).

Savelyev E.P. Ancient history of the Cossacks. M., Veche, 2008 (based on materials from the publication 1915–1918).

Information