Defeat of the Russian army near Smolensk

King Vladislav IV near Smolensk. Painting by Jan Matejko

Bet on Russian revenge

Russia was defeated in the Russo-Polish War of 1609–1618. The Poles, taking advantage of the Troubles in Russia, captured the Smolensk and Seversk lands, which Moscow had recaptured from the Poles with great difficulty during previous wars. The Smolensk fortress was of strategic importance, covering Moscow from the western direction. Now Moscow was practically unprotected from the west.

At the same time, there was no complete peace. The Deulino truce with Moscow was viewed by the Poles as a temporary respite. The lords constantly carried out provocations on the border, did not recognize Mikhail Fedorovich as Tsar, retaining the royal title for Prince Vladislav. Obviously, a new war was ahead.

The de facto ruler under the young Tsar Michael was his father, the cunning Patriarch Filaret. One of the active participants and organizers of the Troubles. Filaret was preparing for war. It seemed that the opportune moment had arrived. At that time, the brutal Thirty Years' War was raging in Europe. The Czech Republic rebelled against the German emperor. The German Catholic and Protestant prince-electors immediately began to fight. Spain, the Netherlands, the Italian principalities, Hungary, France, Denmark and Sweden joined. Poland was part of a coalition of Catholic states led by the Habsburgs.

In this situation, Russia's natural ally became the ardent opponent of the Habsburgs - Protestant Sweden. Sweden at this time created the best army in Western Europe, smashed the Germans, Danes, Spaniards and Poles, and captured Riga. The Swedish king Gustav II Adolf was one of the most educated rulers of his time, loved mathematics and history, proved to be an excellent commander.

Moscow decided to postpone the issue of returning access to the Baltic and began to establish friendship with the Swedish king Gustav II. Sweden and Russia exchanged permanent diplomatic missions. The two powers were actively preparing for war with Poland.

It was beneficial for the Swedes to cooperate with Russia.

Firstly, it was possible to calmly fight in Europe without fear of opening a second front with Russia. Russian military and material resources were used against Sweden's enemies.

Secondly, Sweden, having formed a large army, was in desperate need of money. Here Russia's help was serious. The Russian kingdom supplied grain to Sweden, which the Swedes resold with great profit in Holland. For six years 1628–1633. The export of cheap grain from the Russian state brought the Swedish royal treasury 2,4 million Reichstalers in net profit.

In turn, Sweden provided certain military-technical assistance to Russia. Of course, not for free. By direct order of the Swedish king, Moscow was given the secret technology for casting light (field) cannons, the use of which on the battlefield gave the Swedish army a serious advantage over the enemy.

At the beginning of 1630, cannon master Julius Koet arrived in the Russian capital and established the production of new cannons in Russia. In 1632, under the technical leadership of another Swedish envoy, Andrei Vinius, the Tula and Kashira military factories, iron smelting and iron-making enterprises were founded. With the help of Sweden, Russia is hiring military specialists, officers and soldiers.

Also, the tsarist government hoped that the Ottoman Empire would be hostile to Poland, and the Crimean Khanate would not attack the Russian kingdom at this time.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth itself there was turmoil. Polish lords and Catholics intensified the persecution of Orthodoxy, Cossacks and peasants in Russian Ukraine (former Kievan Rus, Little Russia - according to Greek sources) constantly rebelled (Zhmailo uprising; Fedorovich's uprising). The Cossacks sent delegates to Moscow more than once. They asked for citizenship to the Russian Tsar.

However, Moscow's plans for a favorable foreign policy situation did not justify themselves. In November 1632, the Swedish king Gustav II died in battle. Sweden, until Queen Christina came of age, was ruled by a regency council headed by Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, who did not want an alliance with Russia. The Chancellor focused on the Thirty Years' War and abandoned the war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

A vassal of the Turkish Sultan, the Crimean Khan, having received a generous payment from the Poles, struck Russia in the south, effectively opening a second front. A significant part of the Russian army during the war with Poland was diverted to the southern strategic direction.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, King Władysław was elected as early as November 1632, and hopes for a long period of chaos in Poland were dashed. The Little Russian Cossacks, or rather their elders, hoping for an improvement in their situation and pinning high hopes on their “patron” Vladislav, did not revolt. On the contrary, the Zaporozhye Cossacks attacked Valuiki, then Belgorod, Kursk and Sevsk.

As a result, at the decisive moment, Russia found itself face to face with the Polish-Lithuanian state. Warsaw received a warning from France that the Russians were preparing for war. Therefore, Poland managed to conclude a truce with the Swedes and was ready for war in the east.

Model of the Smolensk fortress in the historical museum of Smolensk

Military reform

The main attention was paid to improving the organization and armament of the Russian army. The size of the army in 1630 was increased to 92 thousand people. But only a quarter of these forces could be used as a field army. Up to 70 thousand people performed city garrison service.

In order to strengthen the striking power of the army, the Russian Tsardom began a military reform, began to form regiments of the “foreign (new) system” according to the Swedish model, and actively invited foreigners to serve as officers and advisers. At the beginning of 1630, orders arrived in Yaroslavl, Uglich, Kostroma, Vologda, Veliky Novgorod and other cities to recruit the remaining homeless children of the boyars into the sovereign service. They planned to form two regiments of soldiers, 1 thousand people each.

An attempt to form new infantry regiments only from service people “according to the fatherland” (birth) failed. It was necessary to recruit free people of non-noble origin, Cossacks, Tatars, etc., as soldiers.

Alexander Leslie and Franz Zetzner, hired abroad, were supposed to train soldiers in military affairs. Leslie had already served in Russia in 1618–1619, then served in Sweden and returned to Russia as part of the Swedish military mission. In the Russian army, he received the rank of “senior colonel” (it corresponded to the rank of general) and went to the German Protestant principalities to recruit mercenary soldiers.

At the beginning of 1632, the number of soldier regiments was increased to six. Four regiments took part in the campaign against Smolensk, two more regiments were sent to the active army in the summer of 1633.

The tsarist government decided to extend the successful experience of creating infantry soldier regiments to cavalry. From the middle of 1632, the first Reitar regiment began to form, the initial strength of which was determined to be 2 thousand people. Service in the cavalry was honorable and traditional for nobles, so impoverished servicemen willingly enrolled in the reiters. Also, service in the cavalry was paid more generously. The command decided to increase the strength of the regiment to 2 people, forming a special dragoon company. The Reitar regiment consisted of 400 companies led by captains.

Already during the Smolensk War, the government formed a dragoon regiment, two soldier regiments and a separate soldier company. The dragoon regiment consisted of 1 people, divided into 600 companies, each with 12 privates. The regiment also had its own artillery - 120 small guns.

By the beginning of the war, six regiments were ready - 9 thousand soldiers. Just three and a half years before and during the war, 10 regiments of the new system were formed, with a total number of about 17 thousand people.

They also recruited mercenaries. The recruitment of four mercenary regiments was carried out by Colonel Leslie. In Western Europe, 5 thousand people were recruited. However, this experience was unsuccessful. The Thirty Years' War was in full swing, and the demand for professional soldiers was extremely high in Europe itself. Therefore, Leslie had difficulty recruiting four regiments; their composition was unsatisfactory.

Colonel Alexander Leslie

The beginning of the war. Strike of the Crimean Horde

In the spring of 1632, the Polish king Sigismund III died, and a period of “kinglessness” began in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, fraught with civil war. Moscow decided to use this moment and demonstratively violated the Deulin truce, concluded for a period of 14,5 years (formally it ended on June 1, 1633). In June 1632, a Zemsky Sobor was held, which supported the decision to start a war with Poland.

The decision to attack was not canceled even after the sudden attack of the Crimean horde on the southern regions of Ukraine. In June 1632, the Crimeans devastated Mtsensky, Novosilsky, Oryol, Karachevsky, Livensky and Yeletsky districts. The Crimean Horde violated the instructions of Sultan Murad. This was the first major campaign of the Crimeans in many years of calm.

The Tatar attack delayed the advance of the main Russian forces to Smolensk for three months. Only on August 3, 1632, the advanced units of the army under the command of boyar Mikhail Borisovich Shein and okolnichy Artemy Vasilyevich Izmailov set out on a campaign. On August 9, the main forces set out. The troops marched to the border Mozhaisk, where it was planned to complete the formation of the strike force.

Due to the threat of a second attack by the Crimeans on the southern border, the collection of regiments was delayed until the beginning of autumn. Only on September 10, Shein received a decree to begin military operations against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The 32-strong Russian army with 151 guns and 7 mortars set out on a campaign.

This loss of time will have a fatal effect on the outcome of the campaign.

Despite the autumn thaw, which delayed the movement of artillery and convoys, the offensive was successful. Russian troops in October - December 1632 liberated Serpeisk, Krichev, Dorogobuzh, Belaya, Trubchevsk, Roslavl, Starodub, Novgorod-Seversky, Pochep, Baturin, Nevel, Krasny, Sebezh and other cities and towns.

Siege of Smolensk

On December 5, 1632, a 24-strong army was assembled near Smolensk. But the transportation of artillery dragged on for months. “Great” cannons (“Inrog” – which fired cannonballs of 1 pound and 30 hryvnias, “Stepson” – 1 pound 15 hryvnias, “Wolf” – 1 pound, etc.) were delivered to the army only in March 1633. Until this time, Russian troops were in no hurry to storm the first-class fortress and were engaged in siege work.

Six miles from Smolensk, on the left bank of the Dnieper, a fort with “warm huts” was built and two bridges were thrown across the river. The soldier regiments stood close to the city on the south-eastern side and built trenches and cannon towers. Part of the troops was advanced to the Orsha and Mstislav districts to block the 6-strong detachment of Gonsevsky and Radziwill, which was stationed near the village of Krasnoe, 6 versts from Smolensk.

The Polish garrison numbered, according to defectors, about 2 thousand people. The defense of Smolensk was led by Samoilo Sokolinsky and his assistant Yakub Voevodsky. The garrison had significant food supplies, but lacked ammunition. The Poles, despite the insignificance of the garrison, were able to hold out for 8 months until the arrival of the Polish army.

Smolensk was a powerful fortress, which could only be taken with strong artillery and a proper siege. The time chosen for the siege was unfortunate. The best months were spent due to the threat of the Crimean horde. Usually, with the beginning of late autumn, the troops were withdrawn to winter quarters. Deviation from this rule, in the absence of a regular supply system for the field army, often ended in severe defeats for troops that operated in isolation from the main bases. The siege of Smolensk confirmed this rule.

Winter 1632–1633 Russian troops limited themselves to blockading the fortress. And it was not complete, and Gonsevsky was able to transfer reinforcements to Smolensk. Only on the night of Christmas, a surprise assault was attempted, but the Poles were ready, and the Russian command stopped the attack.

After the artillery was delivered, part of the city’s fortifications was destroyed by cannon fire and mine digging. At the same time, the supply of ammunition was slow; when it ran out, the enemy had time to restore what was destroyed. The Poles managed to build an earthen rampart with artillery batteries behind the walls and successfully repelled two Russian assaults - on May 26 and June 10, 1633. These failures demoralized Shein's army, which was already tired of the long winter siege. Russian troops switched to a passive siege. In addition, the group of Gonsevski and Radziwill constantly worried the Russians.

The commander of the Advanced Regiment, Prince Semyon Prozorovsky, proposed to attack and destroy Gonsevsky's minor forces before they received help. But the commander-in-chief took a wait-and-see attitude, giving the initiative to the enemy.

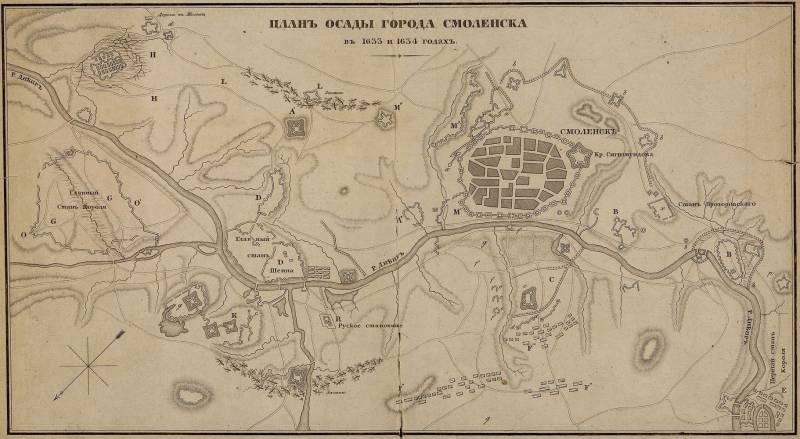

Reconstruction of the plan for the siege of Smolensk. Beginning of the XNUMXth century.

Other directions

Military operations were not limited to the siege of Smolensk. Russian governors tried to strike at the enemy in other directions. In turn, the enemy tried to seize the initiative.

At the end of December 1632 - beginning of January 1633, enemy troops penetrated Sebezhsky district and near Putivl. This attack was repelled quite easily. Russian archers and mounted Cossacks overtook and destroyed Korsak's detachment (20 people) on the Orley River, 200 versts from Sebezh. At the end of January, near Sebezh, another enemy detachment under the command of Colonel Komar was defeated. On February 27, 1633, a 5-strong Lithuanian detachment under the command of Colonel Pyasochinsky tried to capture Putivl. Voivodes Andrei Mosalsky and Andrei Usov repelled the enemy attack and, making a sortie, defeated the enemy.

In March 1633, a 2-strong enemy detachment under the command of Colonel Volk attacked Starodub, but was unable to capture the well-fortified city. In April, the Poles unsuccessfully attacked Novgorod-Seversky, and in May they attacked Putivl again. In June 1533, a 5-strong Zaporozhye detachment crossed the southern Russian border. The Cossacks took Valuyki and besieged Belgorod. But on July 22, 1633, during the assault on Belgorod, the Cossacks suffered a heavy defeat, losing only 400 people killed, and retreated. During the assault, the defenders staged a sudden sortie, destroying the siege equipment and putting the Cossacks to flight.

In the north-west, Russian troops under the command of Peter Lukomsky and Semyon Myakinin at the end of May 1533 marched from Velikie Luki to Polotsk. Polotsk was severely devastated, the settlements and the fort were burned, the Lithuanians were able to hold only the inner castle with great difficulty. On the way back, Russian troops completed the destruction of the Polotsk district. In the summer of 1633, Russian troops carried out raids on Vitebsk, Velizh and Usvyatsky places.

The Poles take the initiative

In the summer and autumn of 1633, a strategic turning point occurred in the war in favor of Poland. In May-June 1633 there was a major invasion of the Crimean-Nogai troops. The Tatars, under the command of the “prince” Mubarek-Girey, invaded the southern Russian districts. Crimean and Nogai detachments broke through the line on the Oka River and reached Kashira. Large territories of Moscow, Serpukhov, Tarusa, Ryazan, Pronsky and other districts of the Russian kingdom were devastated.

Russian forces were diverted to other directions. The army near Smolensk failed to be seriously strengthened. Moreover, many nobles and boyar children, whose estates were located near the “southern Ukraine,” deserted in order to protect their possessions. The escaped Cossacks and soldiers united into groups and detachments. The authorities were unable to stop their exodus; they barely managed to avoid new unrest in the rear.

Gonsevsky received strong reinforcements, strengthening to 10–11 thousand people and went on the offensive. On July 29, the Poles tried to break through to Smolensk, but were repulsed by the troops of Prince Prozorovsky, who led the Advanced and Sentry regiments (the governor of the Sentinel regiment, Bogdan Nagoy, died in July 1633). There were over 4 thousand soldiers in two regiments. In August, Prozorovsky was reinforced by the regiment of William Keith (1,5 thousand soldiers) and the Reiter regiment of Samuel Charles d'Ebert (2 people).

On August 13, the Poles attacked again. The Polish cavalry overthrew the Russian hundreds and pursued them. It turned out that this retreat was false. The Polish cavalry was ambushed, where they were shot by China's soldiers. At the same time, the Russian cavalry turned around and counterattacked the enemy flanks. Gonsevsky is repulsed again.

On August 20, the Poles again attacked Russian positions on the Yasennaya River. Gonsevsky had a qualitative and quantitative advantage in the cavalry, so he tried to lure the enemy into attack by his hussars. The Russians held their positions, under the cover of artillery. The battle continued for several hours with varying success. Russian reiters threw back the enemy's Cossack banners, then the Polish hussars threw back our cavalry. Without achieving any visible success, the Poles retreated.

Meanwhile, on May 9, 1633, the Polish army set out from Warsaw to help the Smolensk garrison. King Vladislav wanted to decide the outcome of the war in his favor with one blow. On August 25, his 15-strong army approached Smolensk. Zaporozhye hetman Timofey Orendarenko brought 10–12 thousand Cossacks to the aid of the king, according to other sources – up to 20 thousand.

Shein by this time had already lost a significant part of the army due to mass desertion; many service people were returning home after learning about the Tatar invasion. The troops were demoralized by the long stand. Foreign mercenaries began to leave their positions and go to the Polish camp. In such a situation, Shein did not dare to give battle and acted defensively.

The siege has been lifted

On August 28, 1633, Vladislav’s regiments launched an assault on Russian fortifications. The main attack of the Polish army was aimed at Pokrovskaya Mountain, where the defense was considered the weakest. 1 thousand infantry and cavalry were sent against the regiment of Yuri Matheson (by that time it consisted of about 300 people). Russian soldiers held the fortifications on the mountain, they failed to break through their defenses, and the Poles retreated.

On September 11 and 12, the Polish-Lithuanian army again attacked Pokrovskaya Mountain. Matheson's regiment again showed tenacity and repulsed all attacks. But on September 13, Commander-in-Chief Shein ordered the positions to be abandoned. On September 18, the Poles attacked the southwestern positions of the Russian army, which were defended by the regiment of Heinrich von Dam (about 1 people). All enemy attacks were repelled, but on September 300, Shein ordered that this position be abandoned.

The commander-in-chief narrowed the front of defense, since the greatly reduced troops could not hold their previous positions. On September 20, the main battles took place in the southeast. Prince Prozorovsky held the defense here; after receiving the order to withdraw, he barely made his way to the main camp.

As a result, the Russian army was defeated, the royal army lifted the siege of Smolensk. Shein's army still retained combat capability and could retreat to continue the fight, but for this it was necessary to abandon artillery. The commander-in-chief did not dare to make such a difficult decision and ordered the construction of new fortifications.

On October 9, 1633, Polish troops captured the village of Zhavoronki, cutting off the Moscow road. The mercenary regiment of Colonel Thomas Sanderson and the soldier regiment of Colonel Tobias Unzen (killed in battle) defending Zhavoronkova Mountain, attacked by the hussars, withdrew to the main camp with heavy losses. Shein's army itself came under siege. The Royal Army was unable to destroy the Russian troops in several battles, but completely blocked them, surrounding them with a line of its fortifications.

For four months, the besieged Russian army suffered from food shortages, firewood and disease. In mid-February 1634, under pressure from foreign officers, Shein agreed to begin negotiations with the Polish king on the terms of an “honorable” surrender. On February 21, 1634, the agreement was signed.

Russian regiments with personal weapons, banners, 12 field guns, but without siege artillery and baggage equipment, they received the right to unhindered withdrawal to their border.

The most difficult condition of surrender was the clause on the extradition of all defectors. Shein took away more than 8 thousand soldiers, and about 2 thousand more wounded and sick were left in the camp until they were cured. According to the terms of the agreement, after recovery they were supposed to return to Russia. Half of the mercenaries went into the service of the Polish king.

The Poles tried to develop an attack on Moscow, but the heroic defense of the fortress by the White Voivode Volkonsky (1 thousand soldiers) stopped the advance of Vladislav’s army. Meanwhile, the capital was covered by the regiments of the princes of Cherkassy and Pozharsky. In the southern direction, the enemy offensive was stopped by the Sevsk fortress.

The defeat of the Russian army at Smolensk led to failure in the entire war. On June 4 (14), 1634, the Peace of Polyanovka was concluded between Russia and Poland on the Polyanovka River, which basically confirmed the borders established by the Deulin Truce. Only one city went to Russia - Serpeisk. According to the agreement, Vladislav renounced his claims to the Russian throne, and the title was simply bought back.

Medal in honor of the victory of Vladislav IV near Smolensk in 1634

Information