The growing pains of American aviation. The tragedy of the 57th group

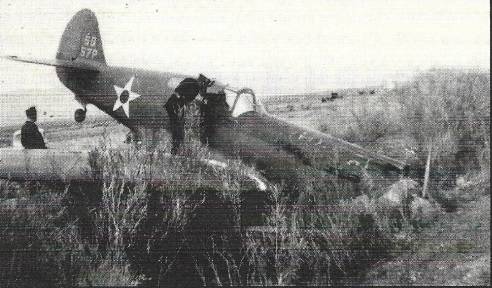

Lt. Ralph Matthews' plane that crashed Oct. 24 in Smith Valley, Nevada.

Many are probably accustomed to the fact that the American aviation is strength and power, a structure that largely helped win many ground battles and bring the United States into the ranks of the victorious countries in World War II. But this was, to put it mildly, not always and not immediately. And American aviation went through a painful period of growth, which was sometimes characterized by outright failures and tragedies.

The 57th Pursuit Group was officially established on January 57, 15 at Mitchell Field, New York, and subsequently transferred to Windsor Locks, Connecticut, in July of that year.

A group of P-40 fighters prepares to take off, Mitchell Field, 1941. These aircraft belong to the 8th group.

In the fall of 1941, planning began for exercises involving the 57th Group. And on October 18, 1941, an operational order was issued, which stated that a mixed group of 25 P-40 fighters (Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk) of the 57th group was to participate in a multi-day group flight. The purpose of the exercise was to test the air defenses around McChord Air Force Base near Seattle and gain experience flying a large group of fighters.

The order did not specify a specific route, only saying to follow the "best available" route. Several refueling and overnight stops were planned, and a ground support team of 25 full-time mechanics and group technicians was planned to follow the fighters in a transport aircraft provided by the 1st Air Force.

Group flight of P-40 fighters of the 18th group, Hawaii, August 1941. At that time, the flight of a group of more than 5 aircraft, especially over a long distance, was a real event.

Major Clayton Hughes, a 40 West Point graduate and former cavalryman, was appointed to lead the P-1929 flight. In 1934, the officer, who considered that the time of the cavalry had passed, achieved a transfer to aviation (United States Army Air Corps) and retrained as a fighter pilot. Among his subordinates, he was known as a campaigner, a tyrant, and most importantly, a pilot who, despite a decent solo flight, clearly lacked the experience of group flights and flight management skills.

The pilots tried not to catch the eye of a man in cavalry breeches and high riding boots, with a stack in his hands. And if this did happen, you had to immediately stand at attention and salute, no matter what you were doing, otherwise problems could not be avoided.

Group photo of officers of the newly formed 57th Group, 1941. In the center with a stack in the rivers is Major Hughes. Second from the left is one of the victims of the future flight - Lieutenant Truax.

Most of Hughes's subordinates received their pilot wings a little more than six months before the scheduled flight. The US Army Air Corps was actively growing, that is, there was a constant shortage of personnel and equipment. But the pilots persistently prepared for the flight, performing single and group flights. At that time there was nothing like it stories American aviation did not occur; this was the first flight of fighters in such numbers over such a distance.

The first flight of the entire group ended in a minor emergency; Lieutenant Miller had to return to the airfield due to a technical malfunction of the P-40 aircraft. The aircraft at that time was still new to American aviation and was poorly mastered by technical personnel, and the qualifications of this personnel often left much to be desired; we recall the sharp increase in the number of aviation and, accordingly, the recruitment of new personnel.

Already on the morning of October 24, only 19 aircraft and pilots remained in service. The rest were unable to continue the flight due to various technical problems, and this despite the mechanics accompanying the flight and the highest priority of the flight itself.

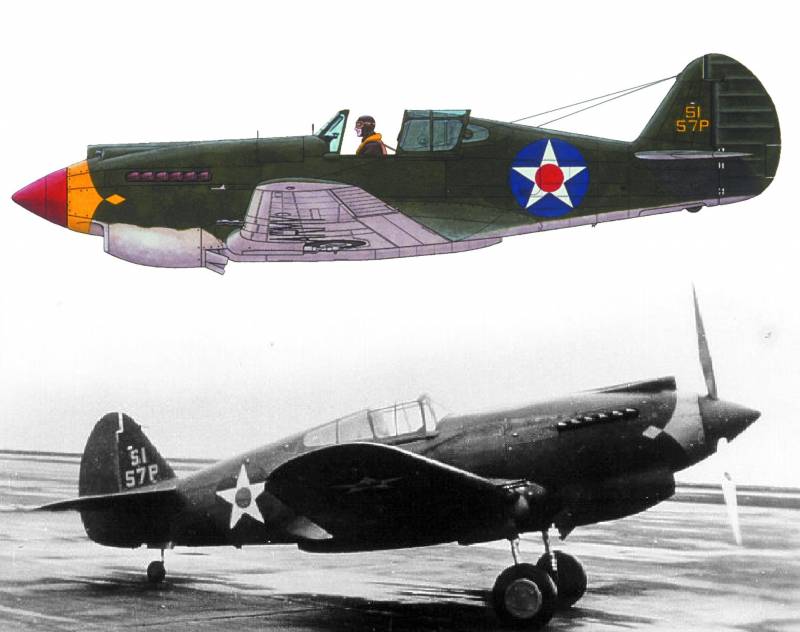

Coloring and designations of aircraft of the 57th group at the time of the events described.

At the morning briefing on October 24, Trooper Hughes ignored the recommendation of the meteorological officer at March Field, where they were scheduled to fly out that day, to delay their flight to the northwest due to bad weather. And it was worth listening to, moist air from the Pacific Ocean and cold October air from the mainland were creating a storm system over Central California, a typical situation for the fall and winter in the Sierra Nevada range.

In addition, Hughes decided to fly to the next point of the route “directly”, through the mountains, and fuel calculations were made based on the direct route. The pre-flight briefing was more formal, and only two pilots were present at the weather and route briefing. There simply weren’t any instructions back then that all pilots in the group had to be notified about the weather and the route - fly in formation and don’t ask questions. What can we say if only two pilots had flight maps - Major Hughes and his deputy. “On the horses!”

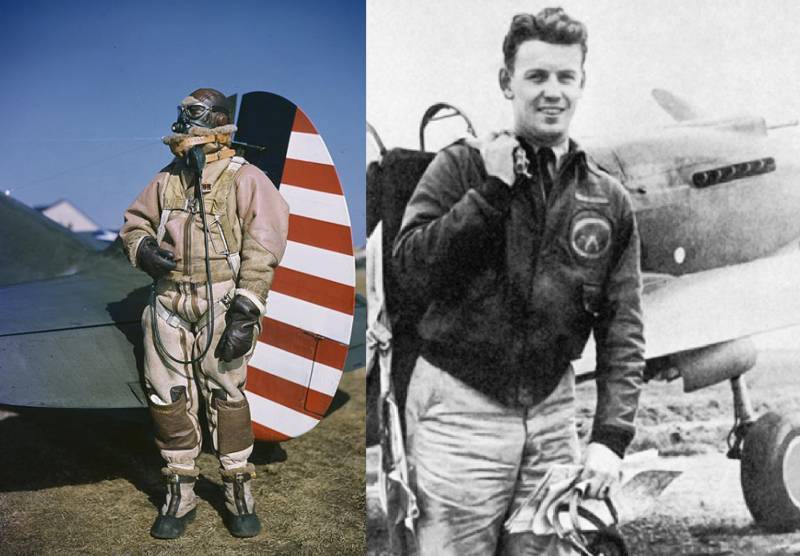

In 1941, despite the growth in aviation numbers, funding clearly lagged behind needs. The pilots in many ways still lived with the realities of service during the Great Depression. The oxygen equipment was varied and worn out; not all pilots had oxygen masks, and those that were available were not equipped with built-in radio microphones.

There was not enough special flight uniform; none of the pilots who took part in the flight had it. We flew in a cotton officer's casual uniform and officer's casual boots (essentially, civilian derby boots). At that time, pilots were simply not given any instructions in case of a forced landing or abandonment of the plane (except for theoretical training on leaving the plane), that is, no one knew what and how to do on the ground in such a situation.

And there was nothing to do; there were practically no portable emergency supplies at that time. They had just begun to appear; the pilots who served in the Panama Canal zone were the first to talk about their need, but not a single pilot from the 57th squadron had anything like this.

How it should have been and how it was. The first photo is an official US Army photograph showing Lt. Gilbert Meyers in front of a P-40 from the 35th Group. The pilot is wearing an A-8 oxygen mask, B-6 flight goggles, a B-3 winter jacket, A-3 pants, a B-5 flight helmet, A-9 gloves, and A-6 boots. The second photo shows Lieutenant Truax in the same uniform in which he went on the flight in October 1941.

When approaching the Sierra Nevada, the group entered cloud cover. It was not possible to rise above the clouds; the oxygen equipment on most of the vehicles was faulty or there were no oxygen masks, plus the cabin heating on the early P-40s was frankly rather weak.

Among other things, in the clouds, Hughes, who clearly had insufficient experience in instrument flight, lost his orientation.

Everything that happened next was the beginning of a real tragedy.

First, the engine of Lieutenant Pease's car malfunctioned, after which it stopped completely. After several unsuccessful attempts to start the engine, Pease decides to abandon the plane, which is losing altitude. Lieutenant Carey, who noticed that Pease was in trouble, accompanied him until he saw the parachute deploy. Exhaling with relief, he decided to return to duty, but realized that he had lost his colleagues in the clouds...

There are only 17 vehicles left in the main formation. Pease himself was more than lucky. He landed successfully, despite jumping over a mountainous forested area and flying through a snowstorm in the mountains. After walking about five miles down the hill, he came across a shepherds' hut, where there was a stove and even bed linen, where he was able to spend the night.

The next day, luck did not leave Lieutenant Pease and, going out to the town of Kennedy Meadows, he found on one of the ranches the only house inhabited at this time of year, the owners of which usually moved to the city in the fall. It was there that Pease was surprised to learn that he was not the only victim of unprofessionalism and circumstances that day, and that a real tragedy was playing out in the skies over California.

Hughes, while the planes had not yet entered dense clouds, had to make a decision regarding the route of further flight. As already mentioned, it was impossible to rise higher. It would be possible to return... But Hughes decided for himself that the mission would be carried out in conditions “close to combat”, and the cavalrymen would not retreat in battle!

Considering that he believed that the group was flying over the lowlands and was already close to the base, Hughes was in no hurry to make a decision. The group entered a completely cloudy area, and the formation immediately fell apart. From that moment on, virtually every pilot was on his own.

Fortunately, most of the pilots managed to get out of the clouds on their own. Lieutenant Mears, who understood that they were approaching a mountain range, even tried to warn Major Hughes about the danger, but the radio was malfunctioning. Mears led a group of two planes out of the clouds and flew them to Smith Valley in Nevada, where they were forced to land due to lack of fuel. Later, all three calmly flew to the final destination of that day's route.

Lieutenant Carey also flew to Smith Valley himself. True, at the Smith Valley airport the runway was not intended for heavy army fighters; all the planes rolled out of it when landing, but only one was damaged by crashing into a drainage ditch and being capped.

A total of 8 fighters landed in Smith Valley that day.

Some of the planes that landed in Smith Valley on October 24. In a small town, the appearance of a group of army fighters was a real event.

The engine on Lieutenant West's plane also stalled, and he also had to abandon the car after several unsuccessful attempts to start the engine when he realized that the fighter was going into a stall.

Almost simultaneously, the same thing happened to Lieutenant Lydon’s car with the same consequences - he had to use a parachute.

Both pilots, separately from each other, landed in the mountains in Kings Canyon National Park. Lieutenant West at first managed to successfully jump from the tree on which his parachute was caught, and then found a hunting lodge, in which a stove and even a fishing rod were found.

The year was 1941, the general fight against smoking was still far away, almost every man had matches or a lighter in his pocket, so there were no problems with starting a fire.

The next day there was a knock at the hut, a delighted West rushed to the door... But instead of rescuers, he saw Lieutenant Lydon, soaked to the skin and frozen, on the threshold. The hut in the mountains became home for the two lieutenants for almost a week. Several independent attempts to descend from the mountains failed, it snowed periodically, and neither the clothing nor the shoes of the pilots allowed them to make long treks on foot in such weather in the mountains.

A few days later, an army B-18 flew over the heads of the pilots, who had prudently lit a signal fire, and dropped a note. Another day passed in communication between the pilots on the ground and in the air using the “we send you a note, you answer us with signal fires” method, after which a walking group of rescuers from the nearby park ranger station advanced to the hut. Both pilots were safely rescued and by the second of November were even reunited with their colleagues.

But all these events paled in comparison to what happened to Lieutenants Long and Birrell. Their planes crashed into mountain slopes. Moreover, according to the testimony of a few eyewitnesses, both planes instantly turned into fireballs, that is, there was still fuel in the tanks. Birrell's body was found and identified, but Lieutenant Long was listed as missing for some time, and only in 1942 was he declared dead.

P-40 model E of the 57th group, which crashed after all the events described, in 1942. The landing gear of the car broke during landing. Accident rates and growth in army aviation numbers went hand in hand.

Unfortunately, plane crashes and the death of pilots were, in general, commonplace events at that time. Especially against the backdrop of the fact that the army and navy were actively creating new aviation units and training new pilots. In the period from October 24 to November 2, 1941 alone, no less than 13 aircraft were lost, 13 crew members were killed and 3 were considered missing, not counting many who miraculously escaped death, but were also wounded and maimed.

However, even against the backdrop of such statistics, the loss of 5 aircraft of one unit in one day looked like something extraordinary. News the incident first began to spread through local media, and then migrated to national media. Newspapers in San Francisco, Sacramento and Fresno lamented the casualties, demanded an investigation and wondered whether the Army needed such dangerous training at all.

At the end of that tragic day, five of the 19 aircraft that took off that morning were destroyed, one was damaged, 5 pilots were reported missing, and two were later confirmed dead. Eight planes landed safely in Smith Valley, 115 miles east of their intended destination. Six aircraft made it safely to McClellan, the final destination of that day's route.

Despite the obvious extraordinary nature of the situation, an order came from the command to continue the flight. That evening, at the post-flight briefing, one of the pilots snapped at Major Hughes, directly blaming him for everything that had happened. Confidence in the command was undermined, the morale of the pilots fell as rapidly as a P-40 with a failed Allison engine.

The next morning, Major Hughes tried to motivate the pilots, reminded them that the task was being carried out in conditions close to combat, as if they were going into battle with the enemy, to which one of the pilots, breaking the chain of command, muttered straight out of formation and without permission:

– Do enemies fly in this weather?

Then everything was about the same, the pilots flew without maps, got lost, the formation fell apart, the planes were lost, the machines suffered from technical malfunctions. On Lieutenant Thompson's plane, one day all the electrics failed, so he had to land the plane at dusk without lighting in the cockpit. The situation was saved by a prudently purchased flashlight with my own funds.

True, the pilot later sadly joked that with the electrics not working, he needed 4 hands to land at night: one to control the plane, the second to control the throttle, the third to extend the landing gear and flaps and, finally, the fourth hand to hold a flashlight .

What added to the piquancy of the situation was that Lieutenant Thompson was landing on the runway of the air base in Fresno, which by that time had not yet been completed and officially put into operation. It’s just that the pilots were again lost in bad weather and without maps, and the fuel supply left few options for choosing a landing site.

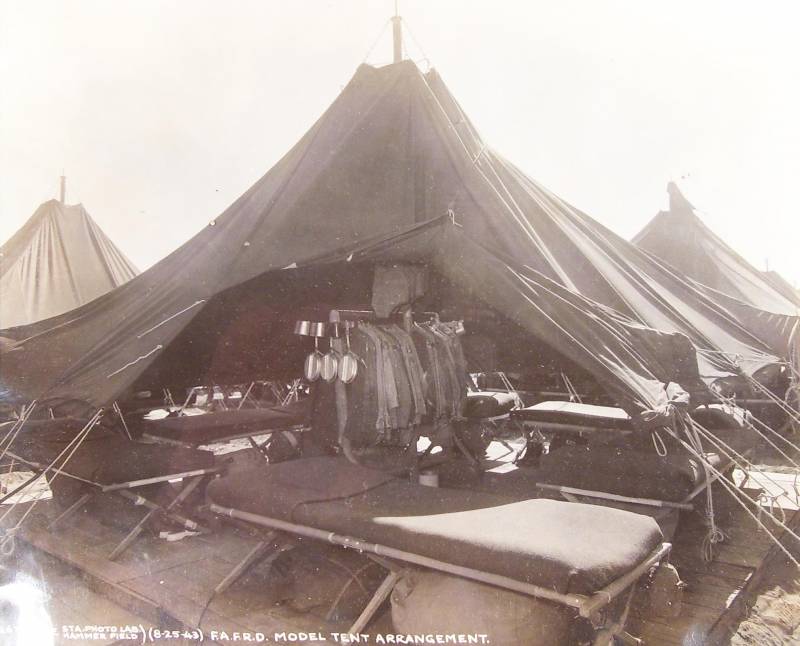

If at the end of 1941 the air base in Fresno was just being completed, then in 1942 life was already in full swing there. The number of personnel and trained pilots grew faster than buildings and barracks were erected; they had to live in tents all year round, fortunately the Californian climate made it more than comfortable. The photo shows one of the tents at the Hummer airfield at Fresno Air Force Base, 1942.

All this could not but lead to a new tragedy, and it happened.

On November XNUMX, three planes crashed into a mountain in the Ross Valley area. Lieutenant Radovic suffered multiple fractures, and Lieutenants Truax and Speckman were killed.

The flight ended on November 4. By the evening of that day, ten of the original 19 P-40s that had been able to reach the starting point of the route (out of 25) March Field on October 24 had returned to their starting point. Over a twelve-day period, during a flight of approximately 2 miles, the 500th Group suffered horrendous losses even by the standards of those turbulent times.

Three pilots were killed, one was listed as missing (actually killed), three were slightly injured, one was seriously injured, eight aircraft were destroyed and one was severely damaged. And all this without any enemy opposition at all and in our own airspace. Several planes also crashed during search and rescue operations at crash sites on October 24 and November 2.

Immediately after the end of the flight, Major Hughes was relieved of command of the 57th Group. An investigation was carried out, as a result of which, in general, no one was punished. It was clear that, despite the obvious miscalculations of the immediate commander of the unit, there were no clear procedures and regulations that could be “foolproof.”

In addition, it was not Hughes himself who made the decision to continue the flight on October 24, he received the order. Based on the results of the investigation, the procedures for conducting pre-flight instructions and briefings were revised, the powers of flight control officers and meteorologists were expanded, the development of NAZs for all army aviation pilots was finally begun, and much more.

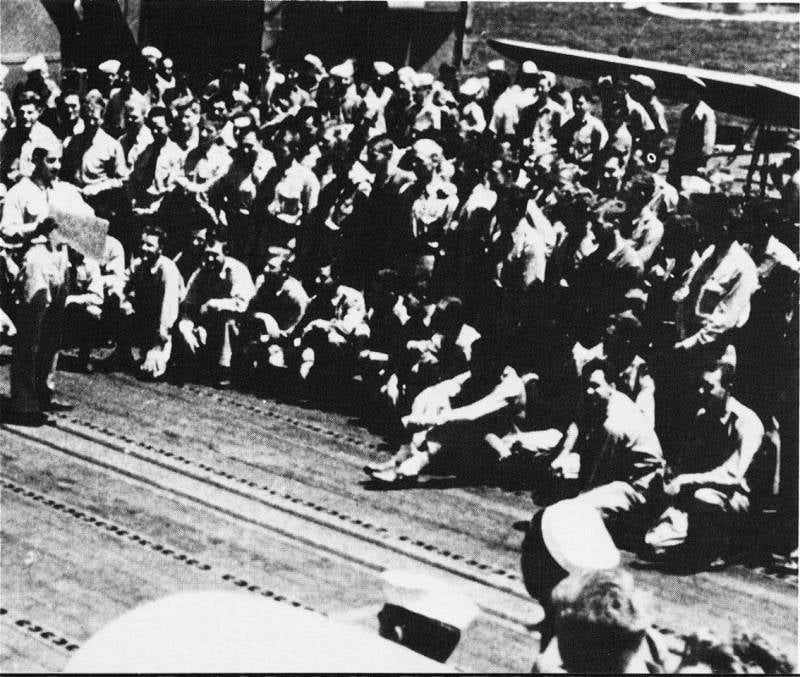

Pilots of the 57th Group (by that time already a fighter group - Fighter Group) on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Ranger (CV-4), from which they will have to take off on July 19, 1942. There are also participants in the tragic flight of October-November 1941 in the photo - Lieutenants Thomas and Barnum.

The surviving pilots of the 57th Group continued to serve, one of them even rose to the rank of brigadier general, and the 57th Group itself, later renamed the Fighter Group, fought in the Mediterranean theater of operations, where it became famous for its participation in the Palm Sunday Massacre ), but that's a completely different story.

Information