Russian riot

Fight with the Pugachevites. N. N. Karazin

250 years ago, the uprising of Emelyan Pugachev began. On September 28, 1773, Pugachev, who took the name of Emperor Peter III, published a manifesto, which granted the Cossacks ancient Cossack liberties and privileges.

Pugachevshchina

While Russian weapon covered itself with glory on the banks of the Danube, in the deepest Russia an abscess called Pugachevism broke out. This is a deeply tragic episode of the Russian stories - actually a civil war of the XNUMXth century. Or, as Soviet historiography called it, a peasant war caused by the strengthening of feudal-serf oppression.

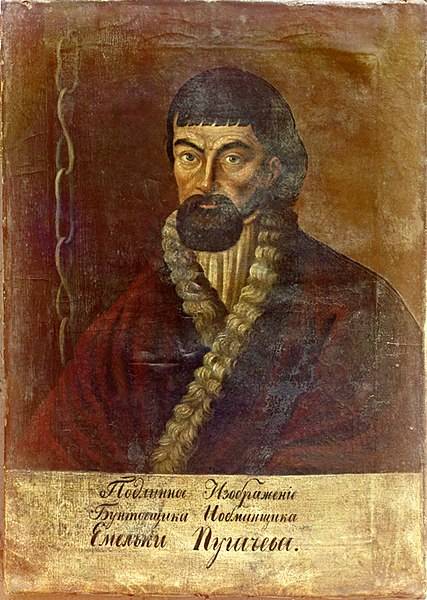

Don Cossack Emelyan Pugachev, as military historian A. Kersnovsky noted, “was a typical “thief” in the old Russian sense of the word, and decided to “shake Moscow.”

Emelyan Ivanovich was born in the village of Zimoveyskaya, Don Region. The year of his birth is not established. A participant in the Seven Years' War with Prussia, from 1763 to 1767 he served in his native village. Participant in the war in Poland with the Bar Confederation, then with Turkey. A fugitive Cossack who went to the Yaik River (Ural) and declared himself Tsar Peter Fedorovich, who “miraculously escaped.” In general, the legend is traditional for the Troubles of the early XNUMXth century.

Pugachev was arrested and sent for investigation to Simbirsk, then to Kazan. At the end of the investigation, Pugachev was ordered to be “punished with whips” and sent to hard labor in Siberia. The Cossack escaped in May 1773 and in August reached the land of the Yaitsky army. In September, hiding from search parties, Emelyan Ivanovich, accompanied by a group of Cossacks, arrived at the Budarinsky outpost, where on September 17 (28), 1773, his first decree to the Yaitsky army was announced, which granted the Cossacks the same liberties. From here a detachment of 80 Cossacks headed up the Yaik. New supporters joined along the way. Thus began the uprising, which became a whole war.

The ground for the uprising was already ready. The Yaik Cossacks, who for a long time enjoyed the advantages of remoteness from the central government, in the XNUMXth century lost most of the elements of self-government and the election of elders and atamans. The army was divided into two parts. The "seniors" were satisfied with their position. The simple “army” repeatedly rebelled against innovations and demanded will.

Emelyan Ivanovich, declaring himself sovereign, gave the rebellion the appearance of legality, promising to return the Cossacks to their former liberties. The name of Peter III was also popular among the Old Believers, who, since the time of Nikon, had been subjected to terror and repression by the state. The Bashkirs, who rebelled more than once and were severely punished, also cherished the hope of returning to the old free times, also took Pugachev’s side.

All this was superimposed on the strengthening of the serfdom system and the growth of social injustice under the Romanovs. The people were divided into “European” nobles, educated and wealthy, who essentially became colonizers in the vast peasant Russia, and the rest of the people, mostly peasants. The peasants bore all duties, paid taxes, fought, and built an empire. And all the benefits were received by the “Europeans”.

Moreover, they were now exempted from compulsory military and government service. That is, now they did not pay a “tax in blood” for their privileged position. The noble landowners got the opportunity to live the life of a social parasite, take advantage of the labor of peasants and workers, organize feasts, balls and hunts, and do nothing for the state.

Social injustice has reached its highest point. This was the black page of the “golden age” of Catherine the Great. The Russian Empire achieved great success in foreign policy, but the enslavement of the people reached its highest stage. Which became the basis of the peasant war.

Yaitsk Cossacks in the campaign (watercolor of the late XVIII century)

“The Russian revolt is senseless and merciless”

The Yaik border line consisted of a number of weak fortresses and posts - villages occupied by garrisons who were no longer accustomed to service. The soldiers were elderly and disabled, and the Yaik and Orenburg Cossacks quickly went over to the side of the rebels. Almost all of these fortifications became easy prey for the Yaik Cossacks, experienced in military affairs. Officers who turned out to be faithful to the oath were exterminated, and the garrisons were annexed. Only Yaitsky town survived. From there the Pugachevites moved up the Yaik to Orenburg.

The forces of “Sovereign Peter III” grew quickly, and soon the detachment became a whole horde. When occupying small fortresses, the rebels received dozens of cannons. Already on October 5 (16), 1773, Pugachev’s 20-strong army approached the city of Orenburg. But the city had a relatively strong garrison (3 soldiers and 700 cannons) and good fortifications, so it survived. The siege lasted throughout the winter until March 70 (April 23), 3. The rebels were unable to take the fortress.

Pugachev entrusted the siege to his “general” Khlopusha, and he himself returned to the Yaitsky town. The foreman insisted on taking the capital of the Yaik Cossacks. The siege lasted from the end of December 1773 until April 16 (27), 1774. The garrison of Lieutenant Colonel Simonov (about 900 people with 18 guns) heroically fought back, relying on the internal fortress - the retranchement. The garrison of the fortress successfully defended itself and waited for the siege to be lifted by the corps of General Mansurov.

As a result, the main forces of the Pugachevites lost the entire winter in the unsuccessful siege of Orenburg and the Yaitsky town. That is, initiative and time were lost.

It is worth remembering that at this time the entire combat-ready part of the Russian army was fighting the Ottomans. Meanwhile, the government realized that the threat was great and took measures to eliminate the uprising.

“I’m not a raven, I’m a little raven, and the raven still flies.”

A talented organizer and commander, Alexander Ivanovich Bibikov, arrived on Yaik, and the regiments that arrived from the internal provinces, mostly garrison ones, were subordinated to him. Here it is necessary to note the strength of the empire of Catherine II, the empress’s talent for selecting statesmen and military leaders.

On March 22 (April 2), 1774, in the battle of Tatishcheva, the corps of generals Mansurov, Golitsyn and Freiman’s detachment (7 thousand soldiers in total) defeated the main forces of the rebels (9 thousand). The fight was extremely stubborn. Golitsyn wrote in his report to Bibikov:

The Cossacks, relying on the Tatishchev fortress, made forays and repeatedly disrupted the ranks of the attackers with cannon fire. Golitsyn, Mansurov and Freiman had to personally lead the soldiers to the attack with drawn swords. The rebels' defense became hopeless when the Bakhmut hussars and Chuguev Cossacks came to their rear.

Pugachev decided to retreat; his retreat was covered by the Cossack regiment of Ataman Ovchinnikov. In this fierce battle, the rebels lost about 6 thousand people and all their artillery (32 guns).

The siege was lifted from Orenburg, and then from Yaitsky town. Pugachev and the remnants of his army fled to the Southern Urals. The Yaik region was cleared of rebels.

It seemed that the impostor and the uprising were over. However, on April 9 (24), Commander Bibikov died. Catherine II entrusted the command of the troops to Lieutenant General Shcherbatov as the senior in rank. Golitsyn, offended that he was not appointed to the post of commander of the troops, sent small teams to nearby fortresses and villages to carry out investigations and punishments, and with the main forces stayed in Orenburg for three months.

The Pugachevites had the opportunity to restore their strength and go on a new offensive. Pugachev led his detachment to the Ural mining region, where he found an exceptionally strong social and material base. The proletariat of that time massively supported “Peter III”. In May-June, the Pugachevites captured the middle and lower reaches of the Kama River, occupied Magnitnaya, Osa, Izhevsk and Votkinsk factories. Factories were burned when abandoned.

The rebels were pursued by Colonel Mikhelson, when he caught up, he smashed the Pugachevites. The combat effectiveness of the rebel horde was low. There were few weapons, horses, or experienced soldiers. However, the defeated rebels quickly gathered new hordes, and they were joined en masse by factory workers, peasants, and representatives of the small peoples of the Volga region.

Having again gathered a large army of 20 thousand, the impostor led him to Kazan. On July 12–13 (23–24), the Pugachevites defeated and burned the city, which was not ready for defense. The garrison locked itself in the Kremlin. On July 13, Mikhelson caught up with the rebels and defeated them. On July 15, Mikhelson again defeated the rebels, up to 2 thousand were killed, up to 5 thousand people were captured. With a small detachment, Pugachev fled again and crossed the Volga on July 17.

Despite the constant defeats, the rebellion only expanded. There was a rumor that Pugachev was marching on Moscow. On July 28, a decree on freedom for peasants was read out in the central square of Saransk. The same manifesto was announced on July 31 in Penza. Thousands of Russian, Chuvash, Tatar and Mordovian peasants rebelled. The destruction of estates and reprisals against landowners and officials began everywhere. Some of the newly baptized Chuvash and Mari destroyed churches and killed priests. There was a Russian revolt - senseless and merciless. In the regions affected by the rebellion, noble landowners, officers, officials, and often the clergy were exterminated.

Kazan, Simbirsk, Penza, Saratov and part of the Nizhny Novgorod province burned. A population of more than 1 million people was involved in the peasant war. Two or three Pugachevites raised the volost, a small detachment raised the entire county. Pugachev’s campaign across the Volga region became a real triumphal procession, with bells ringing, the blessing of the village priest and bread and salt in every new village.

Pugachev's court. V. G. Perov

“Forgive me, Orthodox people”

Mikhelson managed to cover Moscow and the central regions in the battle of Arzamas. July-August became critical for the Pugachev era. Moscow is quickly strengthening itself. The shelves are pulled together there. General Panin was appointed as the new commander. He is endowed with extraordinary powers “to suppress rebellion and restore internal order in the provinces of Orenburg, Kazan and Nizhny Novgorod.” The terms of peace with Turkey were softened, troops and Suvorov were called from the Danube Front.

From Penza Pugachev turned south. Researchers believe that he wanted to raise the Volga and Don Cossacks. Also to the south, to his native places, he was drawn by the Yaik Cossacks. On August 7 (18), Saratov was captured. Saratov priests in all churches served prayers for the health of Emperor Peter III. But already on August 11 (22), the city was occupied by Mikhelson, who was hot on the heels of the rebels.

After Saratov, the rebels went down the Volga to Kamyshin, which, like many cities before it, greeted Pugachev with ringing bells and bread and salt. On August 21 (September 1), Pugachev made an unsuccessful attempt to take Tsaritsyn by storm. Having received news of Mikhelson's approach, Pugachev hastened to lift the siege of Tsaritsyn, and the rebels moved to Black Yar. Astrakhan is being hastily prepared for defense. On August 25 (September 6) at Solenikova fishing detachments of Pugachev (10 thousand) were overtaken and defeated by Mikhelson (more than 4 thousand). Government troops pursued the fleeing 40 miles, many drowned in the Volga. About 2 thousand were killed, 6 thousand people were taken prisoner, 24 guns were captured.

Ivan Ivanovich Mikhelson (1740–1807) - Russian military leader, cavalry general, known primarily for his victory over Pugachev

Pugachev with a few comrades fled across the Volga, into the Yaik steppes. There he was captured by his former assistants and handed over to the authorities for a promise of pardon. On September 15, the chieftain was taken to Yaitsky town. The first interrogations took place there, one of them was conducted personally by Suvorov, who also volunteered to escort the impostor to Simbirsk, where the main investigation was taking place.

To transport Pugachev, a tight cage was made, installed on a two-wheeled cart, in which, chained hand and foot, he could not even turn around. In Simbirsk, for five days he was interrogated by the head of the secret investigative commissions P. S. Potemkin and Count Panin.

This episode was described in his research work “The History of Pugachev” by Alexander Pushkin (he was very interested in this history and studied a lot):

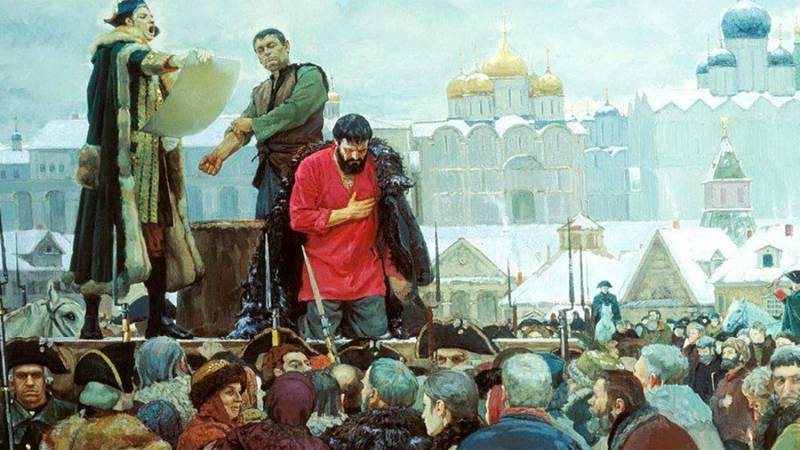

On January 10 (January 21), 1775, an execution was carried out on Bolotnaya Square in Moscow in front of a huge crowd of people. Pugachev behaved with dignity, ascended to the place of execution, crossed himself at the Kremlin cathedrals, bowed to four sides with the words “Forgive me, Orthodox people.” Sentenced to quartering Pugachev and A.P. Perfilyev (one of the main associates of “Peter III”, his “chief general”), the executioner first cut off their heads, such was the wish of the empress.

V. Matorin. Execution of Pugachev

Value

- Pugachev said to Suvorov.

In the Pugachevism one can see the future, even larger-scale Russian Troubles of 1917. Pugachev promised freedom and liberation from the incoming administration to the Yaik Cossacks, Old Believers and Bashkirs. For factory workers, urban bourgeoisie and state peasants – freedom, “nationalization of factories and mines”, duty-free trade and abolition of taxes. He promised the serfs “land and freedom.” Pugachev is a prototype of the Bolsheviks, only in one person, without a party. Therefore, Vladimir Lenin was a big fan of Pugachevism.

The peasant war was drowned in blood. Serf slavery was strengthened. The Romanovs generally tried to destroy any memory of this turmoil. They even renamed the Yaik area to the Ural, and the Yaik army to the Ural. It was forbidden to write about the Troubles and collect materials about it. Pushkin achieved this right only with the personal permission of Tsar Nicholas I.

It is obvious that after the suppression of the unrest, Catherine II should have given freedom to the peasants. Restore social justice. However, the truly great empress, understanding the injustice of this system, could not go against the nobility. Tsar Alexander I could have become a real Blessed One if at the end of 1812, after the victory over all of Europe, when the people helped bury the “twelve languages,” he would have rid Russia of serfdom. But he didn’t dare either.

The reform of 1861 was clearly late, the roots of popular hatred had already taken root, the split of the people became irreversible, becoming the root cause of the disaster of 1917.

“A true portrayal of the rebel and deceiver Emelka Pugachev.” Unknown artist from Simbirsk. 1774

Information