Storm units of the First World War as a model for the Reichswehr of the 1920s

Company of the 9th (Prussian) Infantry Regiment, Jüterbog, 1921

This material completes the series of articles devoted to German assault units in the First World War.

Translate Articles Die Stoßtruppen des Weltkriegs als Vorbilder in der Reichswehr unter Hans von Seeckt (1920–1926), published on the German online resource Arbeitskreis Militärgeschichte e.V.

Author: Linus Birrel

Translation: Slug_BDMP

Development of assault tactics in the First World War

After maneuverable combat operations on the western front were stopped by massive fire from the new weapons - machine guns - and the war took on a positional character in the fall of 1914, “all the thoughts of the military leadership were occupied with how to regain maneuverability at the tactical and operational level” (1).

The Entente military focused on creating an armored vehicle that would combine the firepower of cannons and machine guns with the mobility that the tank eventually became (2).

The Germans, for their part, developed a new concept for the use of available means in the offensive, combining flexibility, mobility, surprise and speed (3). The basis of the new tactics was the attacking actions of specially trained and equipped infantry units, which were supposed to break through enemy defensive lines, called assault lines (Stosstrupps).

Assault tactics were the result of a series of experiments, some of which came from the military high command, and some of which were the result of the initiative of the fighting troops. This tactics constantly evolved under the influence of changes in weapons and battle conditions.

In May 1916, assault tactics in its experimental form were first used on the Western Front by specially formed assault battalions (5). These battalions were subordinate to army commanders and participated in operations in particularly critical sectors of the front. At the same time, these battalions were engaged in training assault tactics for officers and soldiers of other units.

Historian Christian Stachelbeck evaluates these assault battalions as “the locomotive of a continuous process of improving the methods of combined arms combat at the lowest tactical level and training personnel in this” (6). Thanks to this, there was an exchange of knowledge and experience between the active troops and the command, between troops in different theaters of military operations. The Army High Command (OHL) in this case performed the function of a “pragmatic modernization agent” (7).

At the center of the tactics of the assault units was the smallest organizational unit - a squad consisting of a commander - non-commissioned officer and 6-8 soldiers. This section acted independently, but in constant communication with other sections of the battalion. This focus on small units was new, but this idea was in the air in military circles even in peacetime (8).

Combat practice confirmed the correctness of such decisions. On the battlefields of trench warfare, small units were more maneuverable than traditional company or platoon rifle chains and less vulnerable to enemy fire.

Increased maneuverability was also facilitated by the fact that the assault units did not strive to adopt the combat formation prescribed by the regulations, but moved in loose formation, from cover to cover. The goal was to overcome the neutral zone as quickly as possible with the least losses. After this, it was necessary to break into the enemy trenches, if possible, clear them of the enemy and move on. To facilitate the actions of the assault troops, enemy positions had to be previously exposed to artillery fire.

However, to maintain the effect of surprise, the artillery attack should have been short. Line units followed the attack aircraft, suppressing the remnants of enemy resistance and building on their success.

Historian Ralf Raths calls the decisive factors for the success of assault operations fire superiority over the enemy in the direction of attack, loose battle formation, determination and cohesion of the military team (9). In order for a small fire unit to have fire superiority over the enemy, it needs a wide arsenal of combat weapons: a significant number of hand grenades, light machine guns, flamethrowers, mortars.

The fact that assault tactics were able to be applied en masse in large-scale operations, such as the spring offensive of 1918, is the result of the work of experimental assault battalions. If in 1916 assault skills were the lot of a few selected units, then during 1917 they became an obligatory part of infantry operations (10). This happened, among other things, because, along with the training of personnel on the basis of assault battalions, assault tactics were also included in the instructions for training infantry.

Already in November 1916, OHL ordered the creation of a new manual for infantry training, which would take into account the experience of assault operations. The result was the “Training Manual for Foot Troops in War” (Ausbildungsvorschrift fuer die Fusstruppen im Kriege) of 1917 (11).

Each infantry company was ordered to organize an assault group from its best men, trained and equipped on the model of assault battalions. Thus, the number of attack aircraft in the troops grew. The extent to which assault tactics had taken root in the troops by the last year of the war is evidenced by the proposal of the leadership of the Kronprinz Ruprecht Army Group to disband the assault battalions, submitted to the OHL already during Operation Michael in 1918.

The first Quartermaster General, Infantry General Erich Ludendorff, however, believed:

After Operation Michael and others that followed it until July 1918 did not achieve the desired results, about half of the assault battalions were disbanded, since the German command saw no more opportunities to conduct offensive operations (13). However, the tactical successes of these operations are undeniable (14).

Ludendorff himself, back in June 1918, assessed the success of the new infantry tactics as follows: “The new views on methods of attack and on training troops, set out in the regulations, were completely confirmed” (15). However, the first Quartermaster General could not remain silent about the shortcomings: “If there was one thing that was missing, it was time for preparation” (16).

However, this recognition is rather an attempt to obscure the main problem in the implementation of assault tactics, which manifested itself in the spring offensive: the inconsistency of many commanders with the complexity of the tasks assigned to them. Such people acted in outdated but familiar ways or tried (unsuccessfully) to combine old and new (17). The level of preparation of the active compounds also varied greatly (18).

Development of assault tactics in the Reichswehr

To appreciate the influence of assault tactics on infantry tactics of the post-war Reichswehr, it is necessary to study the relevant guidance documents. Although the Reichswehr inherited the personnel and views of the Kaiser's army, the period of its formation in the early 1920s was characterized by the appearance of a series of new regulations.

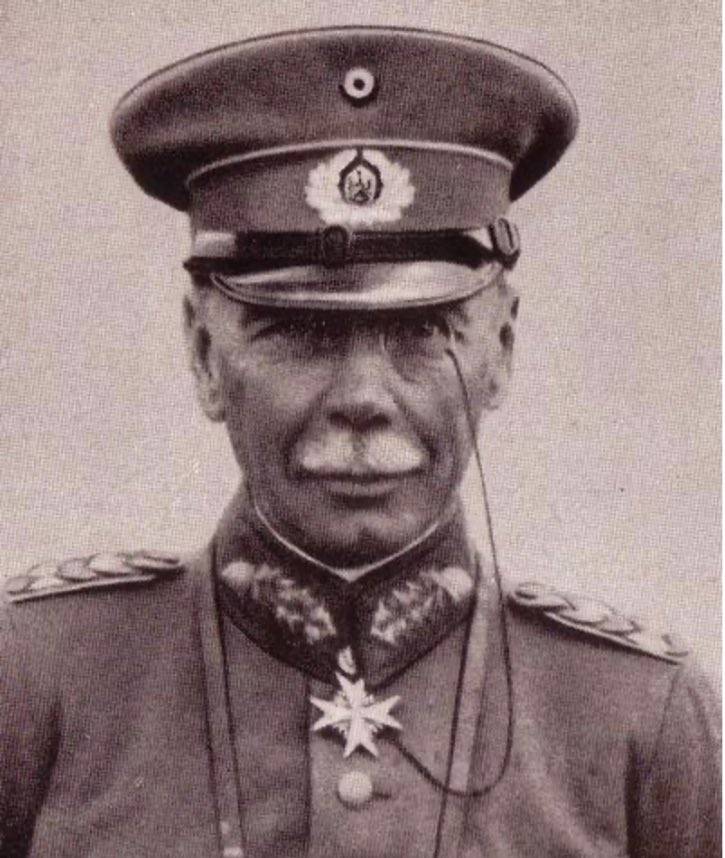

This was explained by the desire of the military leadership to develop a new, realistic military doctrine, taking into account the experience of the previous war and the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. This work was carried out under the leadership of General Hans von Seeckt, who for many years was the commander of the ground forces (19).

General Hans von Seeckt

The most important in terms of infantry actions were two documents:

– Fuerungsvorschrift “DVPl.Nr. 487 Fuerung und Gefecht der verbundenen Waffen” (also called FuG) – governing instruction (statutory – Translator’s note) Nr. 487 “Management of combined arms combat” of 1921, which replaced the field regulations of 1908;

– “H.Dv.Nr. 130 Ausbildungsvorschrift für die Infanterie" (AVI) - instructions for infantry training of 1922, which replaced those of 1918.

FuG was canceled only in 1933, and AVI was revised as early as 1936 (20). This indicates their long-term influence on the development of the German ground forces.

A study of these documents from the point of view of infantry tactics shows that they are based entirely on assault tactics, but the term “assault units” (Stosstrupp) itself is never mentioned. Getting close to the enemy in AVI is described as follows:

This fully corresponds to the assault tactics of the world war, as well as relying on the infantry squad as the main tactical unit.

In the implementation of assault tactics, the Reichswehr charter is even more consistent than its predecessor. It concluded that under the influence of modern weapons, attackers in open areas are often forced to “split even squads into subgroups or scatter completely, with each fighter acting independently” (22).

FuG also follows the principles of assault tactics. It states: “...to reduce losses, the breakthrough is carried out not by rifle chains, but by an echeloned battle formation of mobile groups that are constantly applied to the terrain” (23).

Ralf Raths, in his study of German army tactics before 1918, concludes that the Reichswehr did not develop assault tactics, but diligently followed them: “In the Weimar Republic, the tactical principles developed by the previous war were formalized in the Reichswehr regulations and introduced into combat training” ( 24).

In Reichswehr exercises and maneuvers, it was noticeable that an infantry attack represented the advance of many interacting small groups. In improvised battle groups (Kampfgruppe), which include infantry and artillery pieces, small groups act in concert. A consequence of the command's encouragement of responsibility and initiative was that every junior commander had to be able to lead such a battle group (25).

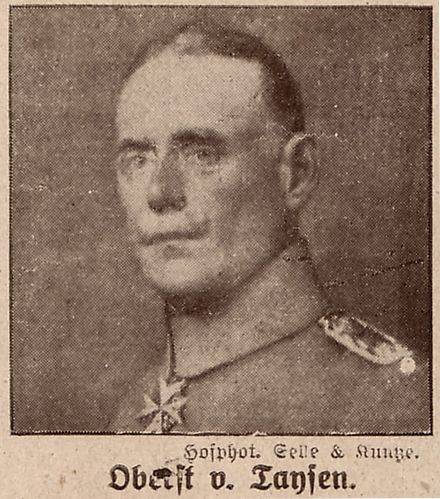

One of the documents that came from the pen of Infantry Inspector Lieutenant General Friedrich von Taysen in March 1924 shows, on the one hand, the deep connection between Reichswehr infantry tactics and elements of assault tactics, and on the other hand, the peculiarities of the originality of the conclusions made by the Germans as a result of the World War. The reason for this was the comments of one unnamed foreign observer at Reichswehr exercises, who doubted the possibility of implementing German infantry tactics in a future war.

Theisen's response is not so much a response to this observer as it is a proof to himself of the correctness of the chosen tactics. First, the author expresses understanding to the observer: “There is no doubt that the attacks of our infantry in exercises can often look like the movement of scattered soldiers” (26).

However, Theisen dismisses the conclusions of the observer: “The impression of fragmentation is not a consequence of the error of our actions... but the skillful use of folds in the terrain by our fighters... A superficial observer sees only individual people, seemingly senselessly running across the field, and does not notice their well-hidden comrades... and on the basis This leads to a conclusion about the senseless bustle of single soldiers” (27).

The author does not agree that this method of action is too difficult for soldiers, since it requires “great independence and the ability to adapt to the terrain, as well as an understanding of tactics” (28). Combat experience confirms that he is right: “Using dense battle formations is the same as “casting out the devil with the help of Beelzebub.” This means not caring about the entire experience of the war” (29).

Theisen passionately defends the new tactics and distinguishes them from the methods of other armies: “We must preserve our forms and methods of action ... They were born of military necessity, worked out in the rear by assault battalions and resting troops in 1917 and were fully justified yourself in the offensives of 1918... Of course, our methods are too complex if you have the opportunity to overwhelm the enemy with corpses in the “Brussilov style” or rely only on combat vehicles and firepower” (30).

General Friedrich von Theisen

The Reichswehr maintained its continuity in the field of tactics with the Kaiser's army, so it is not surprising how much attention was paid to the study and analysis of the experience of the world war. This was done by hundreds of officers of the Reichswehr central command - Truppenamt (an analogue of the General Staff, which Germany was prohibited from having under the terms of the Versailles Treaty. - Translator's note). This process was started by General Seeckt in December 1919 (31).

The influence of supporters of assault tactics led by General Seeckt

In addition to the experience of the war, the direction of development of German military affairs after 1918 was set by another factor. The military leadership was forced to act within the limits imposed by the victorious countries and which determined the size, structure and armament of the Reichswehr. It was forced, despite the restrictions of the post-war world order, to fulfill the main military-political task - ensuring the security of Germany. FuG sets the ambitious goals of a modern, powerful great power, but shows in detail the realities of a small, weakly armed army (32).

Seeckt's solution was to theoretically master prohibited types of weapons and prepare to fight them. “Even without these means of combat, we must be prepared to confront an enemy with modern weapons. Their absence should not stop our desire to act offensively. High mobility, good training and the ability to use terrain features will make it possible to at least partially replace (new types of weapons)” (33).

These lines expressed the view of the commander of the ground forces that the Reichswehr would be able to confront potential adversaries armed without restrictions if it relied on a military doctrine based on the experience of the world war.

It is no coincidence that the principles described above corresponded to assault tactics: good training of troops, mobility and use of terrain features in the offensive. According to Seeckt, the quality of troops is determined not only by “purely military and military-technical training.” Training of personnel “should contribute to the development of independence and fighting qualities of the soldier’s personality, meeting the requirements of modern, technology-rich warfare” (34).

Seeckt believed that “in the struggle between man and technology, one cannot rely on the number of soldiers... Improving the quality of technology should lead to a maximum increase in the qualities of man” (35). Gerhard Gross concludes that Seeckt “sought not to create a mass army, but an elite army, consisting of well-trained and highly motivated fighters” (36). With the term “elite army,” Gross designated a qualitative and quantitative boundary with the mass armies whose forces fought the world war and whose suitability in a future war Seeckt denied, based on previous experience.

“Based on a deep study of the experience of war, the understanding will gradually become established that the time of mass armies has passed, and that the future belongs to small, professional (in the original “hochwertigen” - high-quality. - Translator’s note) armies, suitable for carrying out quick, decisive operations. Thus, the spirit will again triumph over technology” (37).

Seeckt considered the slowness and poor control of massive, relatively poorly trained troops to be the reason for the transition to trench warfare, which ultimately led to the defeat of Germany. At the same time, he proposed a military-professional discussion about the operational control of the armed forces in the era of mass armies (38).

It was conducted not only behind the closed doors of the General Staff (Truppenamt) or on the pages of highly specialized publications, but also in society, for example, in the Militaer-Wochenblatt magazine, an official magazine published three times a week, rich in traditions (39). Both its team of authors and its readership consisted mainly of current and former officers.

Immediately after the war, the Militaer-Wochenblatt became a forum for various discussions about the future of German military affairs. The discussion reflected the perception of reality of that part of society that, along with the monarchy, suffered most from the defeat in the war.

These publications were based on different ideas about the future soldier, the content and duration of his training, as well as his motivation and self-esteem.

If we were talking about assault units during the war, then most often they served as role models on the basis of which infantry training should be based in the future (40).

Ernst Junger

One of the most ardent proponents of this argument was Ernst Jünger. The then lieutenant published two articles in the Militair-Wochenblatt in 1920 and 1921. In them he postulated an image of the soldier and his role, which had its roots in the assault units:

Jünger, a multi-decorated front-line officer, drew on his own experience in assault tactics. “The discipline of a mass army must give way to the self-discipline of the conscious lone fighter” (42). “The excessive formalism of pre-war teachings,” according to the author, contradicted this (43).

The author contrasted the lone fighter with “the faceless mass... since great strength and great value lie within him” (44). He justified the need for movement in this direction, its acceleration by the crushing effect of modern automatic weapons. It forced the division of forces: “There is only one way to significantly increase the combat power of our troops: to make sure that fewer people achieve the same results in the same space that large masses previously did” (45).

His arguments were directed against supporters of mass armies:

Jünger's arguments did not go unanswered.

One of the authors with the pseudonym Julius Frontinus outlined the limits of what was possible for Jünger’s ideas: “The people who are necessary for modern war in Jünger’s vision are few in any army” (47). Based on this, Frontinus came to the conclusion that drill would continue to be an integral part of military training.

As the above examples show, Militair-Wochenblatt served as a field for discussion during the formation of the Reichswehr. They provide insight into the range of opinions about the nature of the new armed forces, although their influence on public opinion is difficult to assess.

In any case, the supremacy in decision-making remained with the leadership of the Reichswehr and Hans von Seeckt personally. His influence was multi-level. It extended both to the development of charters and training manuals that determined the path of development of the Reichswehr, and to the appointment of people to leadership positions. It is not surprising that one of Seeckt’s subordinates, the inspector of infantry, became none other than the above-mentioned Friedrich von Theisen.

He was a proponent of methods of warfare based on the experience of assault units. Serving under his command was Ernst Jünger, who was one of the officers responsible in the commission for the development of new regulations for writing the articles of the manual for infantry training (AVI). Theisen valued and encouraged Jünger, whose publications in the military weekly were fully consistent with the position of supporters of the “elite army” that the Reichswehr leadership and General von Seeckt himself sought to create (48).

Moreover, after the publication of Jünger's novel In Storms of Steel in 1920, one of the reviewers in the official publication Heeresverordnungsblatt professionally assessed it and recommended it as “instructive recommendations for junior commanders and soldiers” (49).

The same can be said of officer Ruele von Lilienstern, who, with the support and permission of the Infantry Inspectorate, published a handbook on infantry squad combat training in September 1921, which went through at least four editions during the 1920s (50).

The consistent introduction of the fighting style developed during the World War into Reichswehr infantry tactics is evidenced by Lilienstern's retrospective remark: “What was the desire and hope when this book first appeared has largely become a reality” (51).

According to the author, the reasons that led to the emergence of assault tactics during the war have not lost their relevance, but quite the opposite: “Our army is small... The greater its internal value should become. The presence of mind and the desire for decisive action by everyone must compensate us for the lack of numbers” (52).

Conclusions

The influence of assault tactics on the development of the Reichswehr can be measured through the guidance documents and training instructions issued in the early 1920s. The publications of supporters of this tactic in professional discussions indicate the same thing.

But they also say that there was no unity in the officer corps in assessing the experience of the World War and its use in the future. Under the leadership of General Seeckt, leading positions in the Reichswehr were occupied by supporters of this tactic, such as Inspector of Infantry Friedrich von Theisen. In turn, Theisen supported officers who sought to introduce assault tactics in the Reichswehr, and those who corresponded to von Seeckt's views on the overall development of the army.

Part of this activity was the promotion of increasing the role of the soldier who meets the high demands of the new tactics. Training troops based on perfect tactics and high individual qualities of fighters was supposed to ensure superiority in battle, even in the absence of modern types of weapons prohibited by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

In the period immediately after the war, it seemed to the Reichswehr leadership that in this way it would be possible to demonstrate the advantages of the concept of an elite army, namely: better control and greater mobility.

List of used literature:

1. Gerhard Groß, Das Dogma der Beweglichkeit. Überlegungen zur Genese der deutschen Heerestaktik im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, in: Bruno Thoß/Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.), Erster Weltkrieg – Zweiter Weltkrieg. Ein Vergleich, Paderborn 2002, S. 143–166, hier S. 150.

2. Robert Foley, Dumb donkeys or cunning foxes? Learning in the British and German armies during the Great War, in: International Affairs 90 (2014), S. 293.

3. Groß, Dogma, S. 151; vgl. Jonathan Bailey, The First World War and the Birth of the modern style of Warfare, in: The Strategic and Combat Studies Institute 22 (1996), S. 11 f.

4. Der Begriff der Stoßtruppen meint im Folgenden die Gesamtheit der militärischen Einheiten des deutschen Heers im Ersten Weltkrieg, deren Angehörige in der Anwendung der Stoßtrupptaktik ausgebildet und hierfür spezifisch ausgerüstet worden waren, um in ge schlossenen Sturm- oder Stoßtrupps eingesetzt zu werden.

5. Ralf Raths, Vom Massensturm zur Stoßtrupptaktik. Die deutsche Landkriegstaktik im Spiegel von Dienstvorschriften und Publizistik 1906 bis 1918, Freiburg 2009, S. 165 f.

6. Christian Stachelbeck, Militärische Effektivität im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die 11. Bayerische Infanteriedivision 1915 bis 1918, Paderborn 2010, S. 99.

7. Ders., “Was an Eisen eingesetzt wurde, konnte an Blut gespart werden.” Taktisches Lernen im deutschen Heer im Kontext der Materialschlachten des Jahres 1916, in: Ders. (Hrsg.), Materialschlachten 1916. Ereignis, Bedeutung, Erinnerung, Leiden 2017, S. 111–124, hier S. 117.

8. Raths, Stoßtrupptaktik, S. 169; vgl. Bruce Gudmundsson, Stormtroop Tactics. Innovation in the German Army 1914–1918, New York 1989, S. 50.

9. Raths, Stoßtrupptaktik, S. 167 f.

10. Ebd., S. 189.

11. Ebd., S. 187 f.

12. Fernspruch vom 14.04.1918 von der Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht an das AOK 2, betreffend der Auflösung von Sturmbataillonen, BArch, PH 10-III/22, S. 39.

13. Raths, Stoßtrupptaktik, S. 166.

14. Gerhard Groß, Mythos und Wirklichkeit. Geschichte des operativen Denkens im deutschen Heer von Moltke d.Ä. bis Heusinger, Paderborn 2012, S. 137.

15. Chef des Generalstabes des Feldheeres, Überarbeitung der Richtlinien und Grundsätze zur Ausbildung der Truppe nach der ‚Blücher-Offensive' (09.06.1918/3/1019), BArch, PH 8/XNUMX, S. XNUMX.

16. Ebd., S. 9.

17. Christoph Nübel, Durchhalten und Überleben an der Westfront. Raum und Körper im Ersten Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2014, S. 136.

18. Stachelbeck, Effektivität, S. 139.

19. Hans von Seeckt war von 1920 bis zu seiner Verabschiedung infolge eines politischen Skandals im Jahr 1926 Chef der Heeresleitung der Reichswehr. In dieser Funktion war er der maßgebliche Entscheidungsträger für die Ausformung des deutschen Militärs und seiner Doktrin. Seine Rolle gewann dadurch noch an Bedeutsamkeit, dass diese Phase grundlegend für den Aufbau der neuen Streitkraft war, deren Wehrgesetz erst am 21. März 1921 verabschiedet wurde. Vgl. Jürgen Förster, Die Wehrmacht im NS-Staat. Eine strukturgeschichtliche Analyze, München 2007, S. 5.

20. Marco Sigg, Der Unterführer als Feldherr im Taschenformat. Theorie und Praxis der Auftragstaktik im deutschen Heer 1869 bis 1945, Paderborn 2014, S. 59, 61.

21. H.Dv. No. 130 Ausbildungsvorschrift für die Infanterie, Heft 1, Berlin 1922, BArch, RH 1/1151, S. 27 f.

22. Ebd., S. 28 f.

23. DVPl. No. 487. Führung und Gefecht der verbundenen Waffen, Abschnitt I–XI, Berlin 1921, BArch, RH 1/125, S. 184 f.

24. Raths, Stoßtrupptaktik, S. 203.

25. Robert Citino, The Path to Blitzkrieg. Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920–1939, London 1999, S. 28.

26. Friedrich von Taysen, Entspricht die heutige Kampfweise unserer Infanterie der Leistungsfähigkeit eines kurz ausgebildeten Massenheeres? Berlin 1924, BArch, RH 12-2/66, S. 1.

27. Ebd., S. 2.

28. Ebd., S. 3.

29. Ebd., S. 4.

30. Ebd., S. 11.

31. Markus Pöhlmann, Von Versailles nach Armageddon. Totalisierungserfahrung und Kriegserwartung in deutschen Militärzeitschriften, in: Stig Förster (Hrsg.), An der Schwelle zum Totalen Krieg. Die militärische Debatte über den Krieg der Zukunft 1919–1939, Paderborn 2002, S. 323–391, hier S. 334.

32. Vgl. Wilhelm Velten, Das Deutsche Reichsheer und die Grundlagen seiner Truppenführung. Entwicklung, Hauptprobleme und Aspekte, Münster 1982, S. 84.

33. DVPl. No. 487, S. 3.

34. Hans von Seeckt, Die Reichswehr, Leipzig 1933, S. 37 f.

35. Ebd., S. 27.

36. Groß, Mythos, S. 154.

37. Hans von Seeckt, Landesverteidigung, Berlin 1930, S. 67 f.

38. Groß, Mythos, S. 152.

39. Zum Militär-Wochenblatt vgl. Christian Haller, Die deutschen Militärfachzeitschriften 1918–1933, in: Markus Pöhlmann (Hrsg.), Deutsche Militärfachzeitschriften im 20. Jahrhundert, Potsdam 2012, S. 25–35, hier S. 28–30.

40. Major Hüttmann, Die Kampfweise der Infanterie auf Grund der neuen Ausbildungsvorschrift für die Infanterie vom 26.10.1922, Beihefte zum Militär-Wochenblatt, Berlin 1924, S. 1.

41. Ernst Jünger, Skizze moderner Gefechtsführung, in: Militär-Wochenblatt 105 (1920), Sp. 433.

42. Ders., Die Technik in der Zukunftsschlacht, in: Militär-Wochenblatt 106 (1921), Sp. 289 f.

43. Ders., Skizze, Sp. 433.

44. Ders., Technik, Sp. 290.

45. Ebd., Sp. 288.

46. Ebd., Sp. 290.

47. Julius Frontinus, Helden und Drill, in: Militär-Wochenblatt 105 (1920), Sp. 541 f.

48. Helmuth Kiesel, Ernst Jünger. Die Biographie, München 2007, S. 165.

49. Tagebuch eines Stosstruppführers, in: Heeresverordnungsblatt 3 (63) 1921, S. 482.

50. Rühle von Lilienstern, Die Gruppe. Die Ausbildung der Infanterie-Gruppe im Gefecht an Beispielen auf Grund der Kriegserfahrungen, Berlin 1927, S. III. Vorname oder Dienstrang bleiben in der Quelle ungenannt.

51. Ebd., S. 1.

52. Ebd., S. 65.

Information