Korea against the Mongols: 1231–1273

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, the situation in East Asia changed dramatically. A new power appeared in the region - the Mongolian state of Genghis Khan. Having created an effective military machine, the supreme ruler of the Great Steppe began a series of wars of conquest, which eventually led to the creation of the greatest empire in the world. stories humanity.

The Mongols smashed their opponents one by one. One of the objects of the Mongolian military expansion was the Korean Peninsula. However, the state of Koryo, located on it, despite its relatively modest size, turned out to be a serious adversary, as a result of which the Mongol conquest of Korea dragged on for almost half a century.

Goryeo before the Mongols

At the beginning of the 918th century, the territory of the Korean Peninsula was occupied by the state of Koryo, founded in XNUMX. It is from him that the word “Korea” known to us originates. Being relatively small in territory, Goryeo was quite developed culturally. The state religion there was Buddhism.

At the same time, the Koryo people successfully defended themselves against attacks from their northern neighbors, repelling in the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries. invasion by the Khitan state of Liao and the Jurchen empire of Jin. Having established peaceful relations with them and formally recognizing their vassalage in relation to them, the Koreans baths (kings) were independent in internal affairs.

However, at the end of the XNUMXth - beginning of the XNUMXth century, Korea was going through difficult times: the country was shaken by coups, rebellions, popular riots and uprisings. The central government weakened, Korean aristocrats actively seized peasant allotments and turned the personally free peasants who lived on them into serfs (nobie). They also created personal squads (cabyon- "home troops"). Increasing social oppression led to the fact that popular uprisings during that period became commonplace.

Within the service class, conflicts intensified between two groups of officials - civil (munban) and military (muban). As in China, the latter played a secondary role, received smaller plots of land for their service and could not occupy the highest posts in the state. Civilian dignitaries often looked at the military contemptuously, regarding them as a kind of personal protection.

During the reign of Wang Uijong (1146–1170), the problems that existed in Goryeo escalated. The monarch did not show much interest in the affairs of state administration, but he spent a lot of money on the construction of new Buddhist temples and holding magnificent religious festivities. Corruption at court reached its peak.

In 1170, the patience of the military snapped, and under the leadership of the military leader Chong Junbu, they seized power in the country, deposing Uijong and enthroning his brother. The new king turned out to be a puppet in the hands of the military, who occupied most of the highest posts in the state. However, a squabble soon began between the commanders who came to power, and in 1179 Chong Junbu was killed by his rivals.

In 1196, the military leader Choe Chunghong overthrew and killed another temporary worker and, without encroaching on the formal power of the wang, established a hereditary military dictatorship of the Choi (Tsoi) clan in Korea, in many respects similar to the Minamoto shogunate in neighboring Japan. The functions of the wang were reduced to ceremonial, while the representatives of the Choi clan became the real rulers of the country. In an effort to create a military base for his power, Choi Chungheong formed a private army in opposition to the state one.

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, the situation in the country relatively stabilized: the new ruler tried to stop illegal seizures of peasant lands, pursued a policy of reconciliation between military and civil officials, and established relations with the Buddhist clergy.

But soon a new danger appeared on the horizon.

First encounter with the Mongols

At the same time, the star of Genghis Khan rose in the Mongolian steppes. Having united the Mongol tribes under his rule, the new lord of the steppes soon attacked Northern China, whose territory was occupied by the Jurchen empire of Jin. The Mongols inflicted a number of defeats on the Jin troops and in 1215 captured Zhongdu (Beijing). They made rather humiliating demands on the Jin, and although the war continued for many more years, the fall of the once great empire was only a matter of time.

The Khitan people, having freed themselves from Jin domination, tried to restore their state. But soon the Mongols began to push the Khitans, and they were forced to retreat to the south. In the autumn of 1216, a large Khitan army crossed the Amnokkan (Yalu River) River and invaded the northern regions of Korea. The Koryo troops managed to repel the Khitans, but new invasions followed in 1217 and 1218. During the third invasion in 1218, the Khitan laid siege to Sogyong (Pyongyang), the former capital of Goryeo. The Koryo troops were able to push back the Khitan, but the invaders hid behind the walls of the well-fortified Kandon fortress. The siege began.

At the end of 1218, a 10-strong Mongol corps (tumen), together with 20 Jurchens from the state of Dongzhen, allied to the Mongols, located on the territory of Eastern Manchuria and the present Russian Primorye, under the pretext of helping Koryo, invaded the territory of Korea and approached Kandon. The Mongol commanders sent a message to the Koreans demanding that they be provided with food and troops. The rulers of Goryeo were forced to give the aliens 000 grain juice. Soon the Kandon fortress was taken and plundered. All booty and 1 prisoners went to the Mongols. Thus, the first acquaintance of the Koreans with the Mongol Empire took place.

Having provided assistance to the Koreans against a common enemy, the Mongols sent a delegation to the capital of Koryo, the city of Kegyong (Kaesong), and concluded an agreement on “friendly relations” with the Korean rulers, which actually meant recognition of Koryo's vassal dependence on the Mongolian state. Leaving a few dozen people in the border town of Uiju to study the culture, language and customs of the Koryos, the Mongol troops left the territory of Korea. The Mongols did not insist on more yet, since the war with the Jin was still ongoing. In addition, Genghis Khan was preparing for a campaign against the rich and powerful Khorezm state and did not plan to open a new front. The small and poor Koryo did not interest the Mongols at that time.

At the same time, after the conclusion of the treaty of 1219, the Mongol ambassadors regularly visited Korea, demanding tribute in the form of fur skins, ink, paper, silk and other fabrics. The payment of the annual tribute placed a heavy burden on the Korean economy, tax burden increased, which caused discontent among the population.

The maintenance of the diplomatic missions of the Mongols also took a lot of money. In contrast to the formal vassalage in relation to the Liao and Jin, dependence on the Mongol Empire turned out to be quite real and burdensome. The son and heir of Choi Chunghong, who died at the end of 1219, Choi U began to be burdened by her conditions.

In 1225, on the way back while crossing the border river Amnokkan, under mysterious circumstances, the Mongol ambassador Chu Chu-yu (Chhak Koyo) and his retinue were killed. The Koryo van categorically denied the involvement of the Koryo government circles in this crime, blaming the brigands for everything. But the Mongols reasonably doubted the veracity of his words.

It is known that the Mongol ambassadors in Koryo behaved extremely defiantly and repeatedly demonstrated insulting behavior towards the van and high dignitaries and aroused hatred both at the court and in the country as a whole. Therefore, it is likely that the death of the Mongol diplomat really became the work of the Koryos, who took revenge on the hated foreigners. Contacts between Goryeo and the Mongolian state were interrupted for several years.

The lull lasted until 1231. Genghis Khan's son Ogedei, elected at the kurultai as a great khan, resumed offensive operations in northern China in 1231. At the same time, part of the Mongol forces was sent to conquer Koryo.

Thus began the era of the Mongol invasions of Korea.

Mongols army

The state created by Genghis Khan was a huge military camp. The Mongolian army was divided into tens, hundreds, thousands and tens of thousands (tumens, darknesses). Each Mongol male between the ages of 15 and 70 was considered a warrior and was attached to a specific unit.

The Mongolian army stood out against the background of the troops of other states with extremely strict discipline: if one out of ten soldiers fled from the battlefield, committed theft or violated an order, the whole ten responded with their heads. The Mongols were distinguished by a rather high fighting spirit and fearlessness in battle. In addition, they were born riders, had extremely high endurance and could stay in the saddle for days.

All Mongolian warriors fought on horseback. Main weapons The Mongol horseman, especially the lightly armed one, had a bow with arrows. In order to intimidate the enemy, the Mongols used arrows with drilled tips that emitted a terrifying whistle when flying. A heavily armed cavalryman fought with a saber or a sword and a long spear with hooks to pull the enemy warrior from the saddle. Mongolian warriors wore leather armor, often reinforced with metal plates.

One of the reasons for the victories of the Mongols was their ability to learn from the conquered peoples. Already after the first victories in China, siege weapons appeared in the army of Genghis Khan - stone-throwing machines, crossbows, battering rams, mobile towers. During the siege, the Mongols actively used fire arrows and incendiary and explosive shells based on gunpowder and oil.

The Mongols paid great attention to intelligence. Before the campaign, they had an idea about the forces of the enemy, his tactics and the terrain in which they were to conduct military operations. Their army was distinguished by high maneuverability and could both be divided into several parts, and quickly gather into a single fist.

In the conduct of hostilities, the Mongols were distinguished by extreme cruelty. It was considered quite normal for them to kill all men capable of bearing weapons in the captured city, and sell children and women into slavery. Rumors about the atrocities of the Mongols, often spread by themselves, flew far ahead of their troops, so many cities preferred to surrender rather than resist.

After the conquest of the Jin Empire, the steppe people were able to significantly increase the number of their troops due to the contingents of the Chinese (Han), Tangut, Jurchen, and others. The huge wealth of China, combined with a first-class military machine, made the Mongols the main force in the vast expanses of Eurasia.

Army of Goryeo

What was the Korean army of the XIII century?

The basis of the military organization of the state of Goryeo was the Two Armies (Igun) and Six Regiments (Yugwi). Despite the formidable name, the Two Armies numbered no more than 3 warriors and were in fact the palace guards. At the same time, the Six Regiments were quite numerous and numbered up to 000 warriors. Some of them defended the capital, some fought on the borders of Koryo.

In addition to the Two Armies and the Six Regiments, provincial troops also ensured peace in Goryeo. Their function was to suppress local riots and protect state borders. Soldiers were often involved in construction work, primarily in the construction of fortresses and other fortifications.

The armed forces of Koryo were recruited at the expense of recruitment - from personally free peasants, one at a time from a certain number of households. In the event of a major war, men aged 16 to 60 could be called up for service.

In the early period of Goryeo's existence, its armed forces successfully defended the country's northern borders from Khitan and Jurchen attacks. However, with the weakening of central authority and military organization, the importance of private troops increased sharply (cabyon)created by local aristocrats. The Choi clan, having seized power over Goryeo, also created its own private guard. She bore the name Toban ("Metropolitan Chamber").

During the period of confrontation with the Mongol conquerors, new military formations were created under the name byolcho ("special forces"). In fact, they were a private army of the Choi clan and significantly outnumbered the state troops in their combat effectiveness. In 1232, the military ruler Choe Woo, worried about the significant increase in crime in the country, formed a night patrol unit, called Yabyeolcho ("Special Night Detachment").

In the future, its numbers increased significantly, and it was divided into chwabyeolcho ("Left Special Detachment") and Ubyeolcho ("Right Special Detachment"). From among the Korean warriors who managed to escape from Mongol captivity, a unit was also created Sinuigun ("Army of the Holy Spirit"). All three military units received a common name Sambyeolcho (“Three Special Detachments”) and accomplished many feats during the war with the Mongols.

Korean warriors wore lamellar armor, which consisted of small metal plates fastened together with leather cords. Another type of armor, known as the "brigantine", was also widespread, in which metal plates were attached to the base not from the outside, but from the inside, which made it more resistant to cutting and piercing weapons. Koryo warriors wore helmets with either wide brim or wings.

It is worth saying that warriors in armor made up a smaller part of the Korean army, since the state provided only weapons, and the fighter had to take care of clothes and armor himself. Naturally, the peasants did not have the opportunity to supply themselves with armor.

In battle, Koryo warriors used long spears, compound bows with arrows, and straight swords. During the wars with the Mongols, defending fortresses from invaders, the Koreans repeatedly used catapults and arrow throwers.

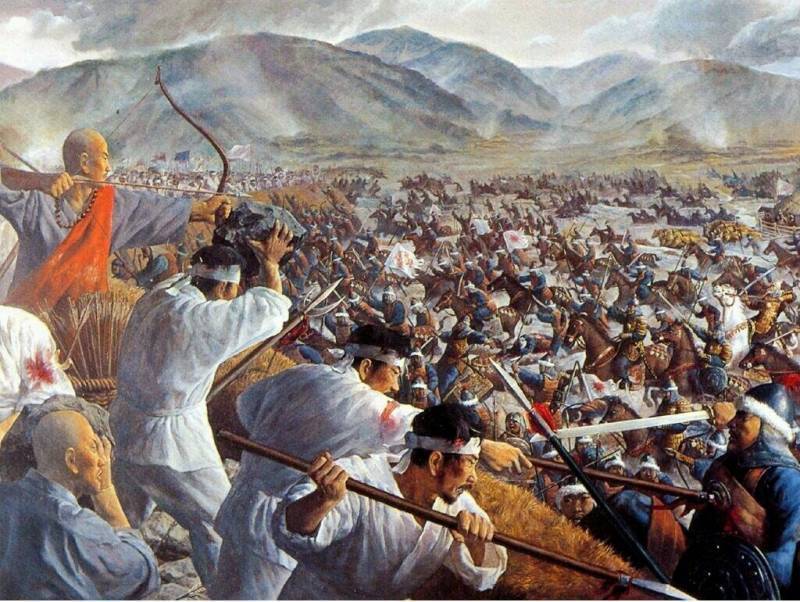

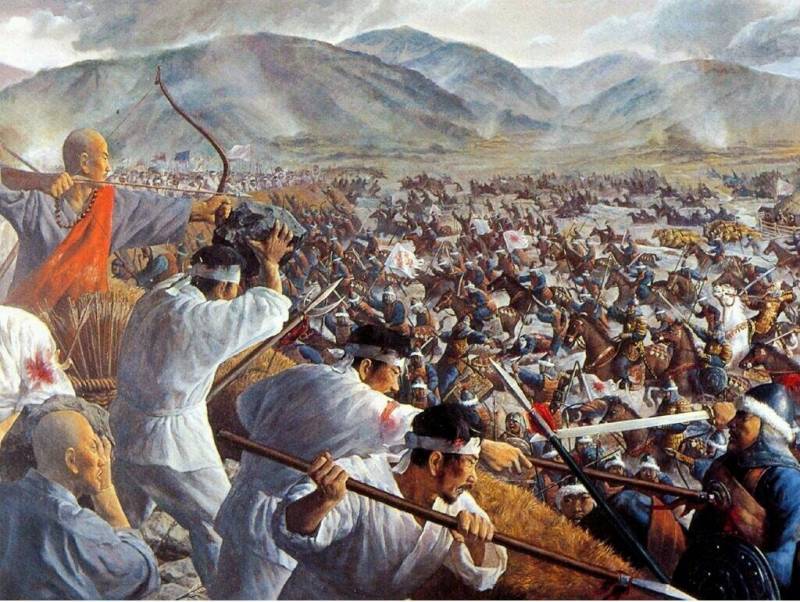

Koryo archers in battle with the Mongols

Invasion 1231–1232

In the summer of 1231, under the pretext of revenge for the assassination of the ambassador, the Mongol army under the command of Saritai crossed the Amnokkan River near the city of Uiju and invaded Korea. The Mongols, almost without resistance, captured several cities and advanced inland. The Koryo rulers did not prepare the country for defense, but the private troops of the aristocrats (cabyon) were too few to offer serious resistance to the invaders.

Nevertheless, the Mongols soon began to have difficulties. Not only the government army acted against the Mongolian army, but also partisan detachments from among the peasants, nobie (serfs) and other representatives of the lower strata of society. Even the rebels who fought against the government at that time turned their weapons against the Mongols. In addition, the commanders of the garrisons of a number of fortresses in the north of the country put up fierce resistance to the invaders.

A striking example of a successful struggle against the Mongols was the defense of the Kuju fortress (modern Kuson). Warriors from the surrounding area, as well as a large number of local militias, were pulled into the fortress. The defense of Kuju was commanded by the warlords Pak So and Kim Gyeongsung.

When the vanguard of the Mongol army approached the fortress, Kim Kyongsong made a sortie and attacked the enemy detachment. The Korean source “Dongguk Pyongam” (“Military Review of the Eastern State”), compiled in the middle of the XNUMXth century and which is essentially an outline of the military history of Korea, describes this battle as follows:

The Mongols retreated, but the Koryo commander did not make the standard mistake of almost all military leaders who opposed the Mongols and pursue them, rightly fearing a trap. Soon the main forces of the enemy army approached. The Mongols surrounded the fortress and began to besiege it. The defenders not only repelled all attacks, but also made regular sorties.

After the first setbacks, Saritai made an attempt to persuade the defenders to surrender. To this end, he sent the captured ruler of the fortress Viju to negotiations, but Pak So ordered to cut off his head.

In an effort to set fire to the gates, the besiegers began to roll carts filled with dry grass towards them. Seeing this, the Koreans began to throw red-hot iron rods at the carts with the help of catapults. Dry grass broke out and the Mongols were forced to retreat.

In an effort to take Kudzha, the Mongols drove siege towers to the walls of the fortress, upholstered with ox skins. Under one of the towers, they began to dig an underground passage, but the Koreans began to pour molten metal from the walls and set it on fire. The fire soon spread to other siege towers. Taking advantage of the panic among the attackers, the defenders made a sortie and killed more than 300 Mongol warriors.

And when the invaders began to shell the fortress with 15 large catapults, the besieged dragged various wagons onto the walls and strengthened the walls; at the same time they began firing back with catapults. When the Mongols tried to set fire to the fortress, the defenders managed to extinguish the flames with clay diluted in water. During another assault, a large Mongol detachment, with the help of catapults, managed to make many breaches in the fortress wall, but the defenders of the city quickly eliminated them and managed to repulse all enemy attacks.

Koryo warriors defending the fortress

The siege lasted for 30 days, but Kuju was impregnable, and its garrison successfully repelled all attacks. Then Saritai decided to go with the main forces to the south, inland, leaving part of the army to continue the siege.

Meanwhile, the military ruler Choi Wu hastily gathered an army to repulse the Mongols. It was joined by guerrilla units, militias, personal troops of the Choi clan, and even rebel peasants. So, a 5-strong detachment of rebels from Masan joined the government troops. The Korean army moved north and entered the province of Hwanghae-do in the northwest of the Korean Peninsula.

Soon, the Korean army was subjected to an unexpected blow from the vanguard of the Saritai army near the Tonsonyeok postal station (modern Ponsan).

When the defeat of the Koreans seemed inevitable, the situation was saved by detachments of peasant rebels from Masan, who showed outstanding courage and managed to repel the attack of the Mongols. Nevertheless, the Koreans suffered heavy losses in the battle and withdrew their troops to the Anbuk fortress (modern Anju). Saritai took advantage of this and approached the Anbuku with an army. The Korean commanders decided to give battle, but were defeated.

The Koreans are defeated

After defeating the Korean army, the Mongols easily occupied a number of cities in Korea. Saritai returned to Kuju and resumed active operations to capture the fortress, but the defenders still made sorties and inflicted heavy losses on the Mongols. Attempts to take the fortress and this time ended unsuccessfully for the besiegers.

At the same time, the Mongol forces operating further south were able to reach the capital, Kagyong. Soon Saritai approached the city with the main forces.

Then Wang and Choi Wu, under pressure from the aristocracy, sent an envoy with gifts to the Mongol commander. They agreed to recognize vassalage in relation to the great khan and pay tribute.

Despite this, the Koreans continued to resist in a number of places. The Kuju garrison continued to hold the fortress and agreed to lay down their arms only in February 1232 under pressure from the royal court. Some other cities also surrendered only after a corresponding order from the government of the country.

After the conclusion of peace, Saritai left Korea with his troops, leaving more than 70 governors (darugachi), whose duties included monitoring the implementation of the agreement by the Korean side. They also had to collect tribute from Goryeo. Its size was huge, the winners demanded not only certain goods, but also the sending of artisans to Mongolia and girls for Mongolian harems.

It is not surprising that such terms of the treaty did not suit either the elite or the common people. As soon as the Mongol troops left Korea, Choi Woo advocated the evacuation of the capital to Ganghwa Island in the Yellow Sea. The royal court, ministries and the entire population of Kagyong were to move to Ganghwa. In the event of a new Mongol invasion, the military ruler hoped to sit out on the island and negotiate more favorable peace conditions from the Mongols. The rest of the population had to take refuge on other islands or in the mountains.

Hastily erecting palaces for the Wang and Choi Wu began on Ganghwa. darugachi were slaughtered. The Koryo rulers openly challenged the Mongols, but did not prepare the country for defense.

One of the buildings of the royal palace of the Goryeo period on the island of Ganghwa-do. Author's photo

In the summer of the same year, 1232, the Mongol army under the command of Saritai, already familiar to us, again entered Korea and managed to move far to the south. But at Chhoinseong (modern Yongin - the southern suburb of Seoul), their advance was stopped. The defense was led by Buddhist monk Kim Yun Hu. During the assault on the fortress, an arrow fired by this warrior monk ended Saritai's life.

Left without a commander, the Mongols were forced to interrupt the military campaign and retreat north. Goryeo received 4 years of peaceful respite.

Defense of Choinseong from the Mongols

Subsequent invasions

In 1236, the third Mongol invasion of Korea began. The invading army, led by the warlord Tangu, subjected the country to brutal devastation. The Mongols burned the cities, fortresses, and crops they met on their way. Anyone who tried to resist was mercilessly killed, and the rest were enslaved.

According to some reports, the invaders stole up to 200 people. The Koryo army for the most part consisted of poorly armed and trained militias and could not resist the Mongols. Korean fortresses fell one after another. However, this time too, the people of Goryeo put up fierce resistance. The Koreans resorted to guerrilla warfare. Using their excellent knowledge of the area, they attacked small groups of invaders. The Chukju fortress put up heroic resistance, which is reflected in the pages of Dongguk Pyeonggam:

Taking torches and dry straw in their hands, the Mongols set fire to the fortress and rushed to the attack. But the Korean soldiers came out to meet them, and it was difficult to count the killed Mongols. The Mongol warriors, having surrounded the fortress from all sides, spent 15 days and still could not force it to surrender. They burned the siege weapons and withdrew."

Despite the unsuccessful siege of Chukju, the Mongols ravaged Koryo with impunity, and in 1239 the Koryo authorities were forced to make peace on even worse terms than a few years before.

First, the Korean wang (at that time it was Gojong) had to return his residence to the mainland.

Secondly, he was obliged to visit Mongolia and leave his son-heir as a hostage at the court of the great khan.

Thirdly, the Korean wang had to execute officials who spoke from anti-Mongol positions. However, the Korean government from the very beginning was not going to fulfill these requirements. Wang sent the son of his distant relative to the Mongols under the guise of an heir, while he himself continued to sit out on Ganghwado. Most of the other terms of the contract were also not fulfilled.

Nevertheless, by sending a hostage of royal blood to the Mongols and resuming the payment of tribute, Choi U managed to win 6 years of peace. This was facilitated by the death of the great Khan Ogedei in 1241, after which a struggle for power began in the Mongol Empire. The son of the late Guyuk faced opposition from his sworn enemy Batu (Batu).

Meanwhile, Choi Woo was engaged in strengthening the fortifications on Ganghwa Island and training troops.

The Goryeo authorities also did not forget about religion: in 1236, the restoration of the Tripitaka, a collection of Buddhist texts that had died during the previous Mongol invasions, began. The grandiose scale of the project is indicated by the fact that the new vault, now known as the Tripitaka Koreana, consists of 80 wooden tablets, and took 000 years to complete. The Koryo authorities thus sought to inspire the Koreans to fight against foreign "barbarians" and increase the "karmic merits" of the state, which was to ensure victory over a strong and cruel enemy.

Along with this, in 1246 Guyuk ascended the Mongol throne and decided to bring the Koreans into submission. In 1247, a new Mongol army under the command of Amugan invaded Korea. Many Koreans were again forced to flee from the conquerors to sea islands and mountain fortresses. However, the campaign was unsuccessful.

In 1248, Guyuk died unexpectedly and as a result of the onset of another interregnum, the Mongol troops left Korea. Choi Woo also died soon after, and was succeeded by his son Choi Han.

In 1251, Mongke ascended the throne of the great khan, and in 1253 the Mongol troops once again invaded Korea. This invasion was unsuccessful: the Mongols could not land on the island of Ganghwado, the garrisons of fortresses on the mainland stubbornly defended themselves. Korean guerrilla units fought successfully against small Mongol units. The staunch and effective resistance to the invaders was provided by the city of Chungju, the defense of which was led by Kim Yonghu, the same Buddhist monk who had slain Saritai 20 years earlier. A long siege of the fortress did not bring results, and the Mongols were forced to retreat.

In 1254, the Mongol Great Khan ordered the fifth invasion of Koryo. Commander Chelodai stood at the head of the army. The new commander moved military operations to the southern provinces of Goryeo, which had previously been practically unaffected by the war. This invasion turned out to be especially destructive: the Mongols destroyed all life, killed or enslaved the local population. The scale of the devastation is clearly illustrated by the following passage from Dongguk byeonggam:

The actions of the Mongols led to the decline of agriculture, depopulated entire regions of the country. Famine and epidemics ravaged Goryeo, while the ruling Choi clan, unable to defend the country, continued to collect extortionate taxes from the population. Under these conditions, the authority of the military rulers was rapidly falling.

Despite the external threat, the political elite of Goryeo did not show unity in the fight against the invaders. During the war years, many officials and military leaders of the northern provinces of the country went over to the side of the enemy. A striking example is the commander Hong Bokwon, who rebelled against the central government in Sogyon (Pyongyang) in 1233.

When the troops sent by the ruler Choi Wu suppressed him, Hong fled to the Mongols and entered their service. Subsequently, he was appointed manager of the district in the northeast of present-day China and received captured Korean soldiers under his command.

Subsequently, Hong Bokwon took part in the Mongol campaigns against Koryo. With the help of Korean shipbuilders and sailors who fell into their hands, the Mongols began to prepare for a landing on Ganghwado. The head of the ruling clan, Choi Ui, who became the new ruler after the death of his father Choi Han, opposed negotiations with the invaders, but at the same time was unable to give them a worthy rebuff, as well as rally the Korean elite around him. This sealed his fate.

Hong Bokwon. Frame from the television series "God of War" (South Korea, 2012)

In 1258 the commanders of the royal guard Sambyeolcho Under the leadership of the dignitary Kim Injun, they carried out a coup d'état and killed the military ruler, thereby putting an end to the 60-year era of the reign of the Choi family. A group of senior officials, who took power into their own hands, advocated peace negotiations with the Mongols.

At the request of the conquerors, the Koryo crown prince went to Mongolia. He was received by the new great khan Kublai, who later established the Yuan dynasty in China, and secured lenient terms of surrender. The court of the wang had to return to the mainland, and the defenses on Ganghwa-do were destroyed. The new Mongol emperor promised to withdraw the Mongol troops from Korea and forbid his commanders from plundering the population. Such humanity on the part of Khubilai was explained by the fact that at that time he was busy with the war against the Song dynasty, which ruled in southern China, and therefore did not seek to continue the war with the Koreans.

Soon the news of the death of the Koryo king came to the court of the Mongol ruler, and he graciously allowed the Korean prince to return home and recognized him as the ruler of Koryo. Thus, in 1260, the heir to the throne became a wang and received the name Wonjon. He became a loyal vassal of Kublai. The fighting on the Korean Peninsula ceased, and Koryo seemed to have finally submitted to the conquerors.

Sambyeolcho's last fight

Despite the overthrow of the Choi clan, the king still had no real power. The country was ruled by the military, led by Kim Injun, who was replaced in 1268 by Lim Yong. They advocated an active struggle against the Mongols, while Wonjong used an alliance with them to restore royal power. In Goryeo, a struggle for power began between military officials and the king.

Without going into its vicissitudes, we note that it ended in 1270 with the victory of the monarch, who relied on military assistance from Khubilai. Wonjong moved the capital to the mainland at Kaegyong.

But there were still elite troops on the island Sambyeolcho ("Three Special Detachments"), which served as the backbone of the anti-Mongolian opposition. Their commanders were categorically against the return of the capital to the mainland and the shameful peace with the Mongols.

Wonjong ordered the transfer of troops Sambyeolcho to the mainland, intending to disband them, but they refused to follow orders. Wang sent commander Kim Chiji to Ganghwado, ordering him to capture the name lists. Sambyeolcho. According to the Korean dynastic chronicle "Koryo sa" ("History of Koryo"):

An uprising began, led by the commander Bae Junson. As it says in "Koryo sa",

Sambyolcho troops who rebelled against the Mongols

The rebels captured Ganghwa Island, proclaimed one of Wonjong's distant relatives (wang On) king and even created their own government. However, the proximity of Ganghwado to the capital and its vulnerability to government troops and Mongolian detachments led to the fact that the rebel warriors, along with their families, were forced to relocate to the island of Jindo, located southwest of the Korean Peninsula.

By raiding the mainland and nearby islands, the rebels were able to block trade routes and cut off the capital from food supplies from the southern provinces of the state. Chindo became a place where opponents of Mongol rule began to gather, of which there were many, especially among the lower strata of the population.

Wang Wonjon, alarmed by the success of the rebels, asked the Mongols for military support. In a letter to Khan Kublai, he described the current situation as follows:

The Mongol emperor responded and sent troops to help his vassal. The joint Korean-Mongolian army began hostilities against Sambyeolcho.

In the summer of 1271, a 10-strong landing force landed on Chindo Island and within 10 days broke the resistance of the rebellious guards. Bae Junson, one of the leaders of the rebels, died in battle, and the king proclaimed by the rebels was captured and executed. However, most of the warriors Sambyeolcho led by commander Kim Tongjong managed to escape on ships. Soon the rebels captured the island of Jeju, on the territory of which there was a small kingdom of Thamna.

After overthrowing the local king, they turned Jeju into their base and made a number of raids on the coast of Korea and captured several minor islands. According to Goryeo-sa, the rebels built on Jeju

However, in the spring of 1273, the island was attacked by a 10-strong Koryo-Mongolian army, which arrived on 160 ships, under the command of Kim Bang Kyung and Xindu. In a bloody battle, the guardsmen, despite their heroism, were almost all killed. More than 1 people were captured, Kim Tongjon, along with 300 associates, fled to the mountains. Not wanting to fall into the hands of the punishers, they committed suicide.

Jeju Island became one of the few territories in Korea that fell under the direct control of the Mongol conquerors. The fact is that it was well suited for cattle breeding, and could also serve as a base for future invasions of Japan. Immediately after the suppression of the uprising Sambyeolcho the Mongols placed a permanent garrison in the island fortress, and turned part of the peasant lands into pastures. Since then, horse breeding has been developed in Jeju, and there are words of Mongolian origin in the Jeju dialect of the Korean language.

Thus, in the spring of 1273, the Mongol conquest of Korea was completed.

The Mongol invasions of Korea devastated the country and caused great damage to the cultural heritage of Korea. At the same time, the conquest of Korea proved to be a difficult task for the Mongol conquerors. Despite the apparent inequality of forces, the resistance of the Koreans to the invaders lasted more than 40 years and ended only with the suppression of the uprising. Sambyeolcho. It can be said without any exaggeration that the anti-Mongolian struggle took the form of a people's war.

In conditions when neither the Korean king nor the military rulers from the Choi clan were able to organize an effective rebuff to the Mongols, lower officials, peasants and nobie steadfastly fought against a formidable enemy. This struggle eventually ended in the defeat of Koryo, but at the same time, the sacrifices made by the Koreans were not in vain.

Unlike the vast majority of countries conquered by the Mongols, Korea, like the Russian principalities, retained its statehood and ruling dynasty. Its dependence on the Mongol Empire eventually came down to the recognition of vassalage in relation to the Mongol emperor and the annual payment of tribute.

At the same time, with the exception of certain territories, including the already mentioned Jeju Island, the Mongols almost did not settle in Korea. Later, Koryo, having become a Mongol satellite, became an important springboard for the wars of conquest of the Yuan Empire against Japan.

Bibliography:

1. Asmolov K. V. The system of organization and conduct of hostilities of the Korean state in the VI-XVI centuries. The evolution of military tradition. Abstract for the dissertation of the degree of candidate of historical sciences. M., 1995.

2. Vanin Yu. V. Feudal Korea in the XIII-XIV centuries. M., 1962.

3. Kurbanov S. O. A course of lectures on the history of Korea from antiquity to the end of the 2002th century. SPb., XNUMX.

4. Lee Gi Baek. History of Korea: a new interpretation. M., 2000.

5. Serov V. M. The campaign of the Mongols in Korea in 1231–1232. and its consequences // Tatar-Mongols in Asia and Europe. Digest of articles. Ed. S. L. Tikhvinsky. M., 1977. C. 150–165.

Information