A little about the industry of the transitional era

Illustration and caption from a textbook stories Middle Ages for 6th grade. “In the workshop of a medieval gunsmith. A cramped, vaulted room on the ground floor of a craftsman's house. A ray of sunlight barely breaks through a small window. In the depths there is a forge, on the right is a grinding wheel and a vise. There are hand tools on the shelves: hammers, drills, tongs, files. The master tries iron armor on the knight. The students help him. At the window, an apprentice with a hammer finishes the chest armor "

skilled in working with gold and silver,

bronze and iron, as well as in working with purple,

scarlet and blue yarn and in the art of carving,

to work in Judea and Jerusalem

with my skilled craftsmen,

chosen by my father David.

Second Chronicles 2:7

Problems of historical knowledge. Not so long ago, VO once again started talking about the "industry" of medieval Europe and the New Age. And as always, many questions arose from incomplete knowledge. And on the other hand, where does he get this most complete knowledge from? From a textbook on the history of the Middle Ages for grade 6? Even a university textbook (say, the one that the author had a chance to study from) left practically nothing in his memory, except perhaps for the fact that workshops were then engaged in production and that at first they were a progressive phenomenon, and then they began to slow down the development of capitalism. But neither about professions, nor about the raw materials of different countries, there was not much talk there, except perhaps about salt, without which it was simply impossible to do without in the same Middle Ages, and then - salted herring was almost the main food of the poor. Rarely, as illustrations, one could see a dry graphic picture depicting a gunsmith, blacksmith or weaver. However, there were many more professions at that time, but there was no opportunity to get to know them then.

Meanwhile, there is a unique source from Germany of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries, which gives us an amazing amount of beautiful images of people of this time at work. And from them you can learn about the professions that existed at that time and even get a little acquainted with the “material base”! And this is not one book, but several, for a couple of hundred years!

And it happened that already in 1388 a charitable organization was created in Nuremberg, which first accepted 12 people in need and helped them find work, having previously taught the craft! Who they were, in what capacity and where they were arranged, was recorded in books called the “Home Books of the Nuremberg Fund of the Twelve Brothers”. Starting around 1425, their books were designed as follows: one-page illustrations of the people they helped, and text usually giving their names and the profession they were engaged in.

Today we continue to publish illustrations from these books, and for different years, so that you can see how these “pictures” themselves have changed from century to century.

And, by the way, whoever is missing in these illustrations: from a baker to a carpenter, from a "loader" to a "sugar producer" - more than 1 images that show us numerous production processes and handicrafts since the 300th century. The images of the masters in the "Books of the Twelve Brothers" have long been known and loved in special and popular science literature, both as research material and as illustrations. However, most of them have remained unpublished to this day. That is why it is especially valuable that the administration of the Nuremberg City Library gave me permission to process and publish them for the readers of VO to familiarize themselves with them.

This is the first…

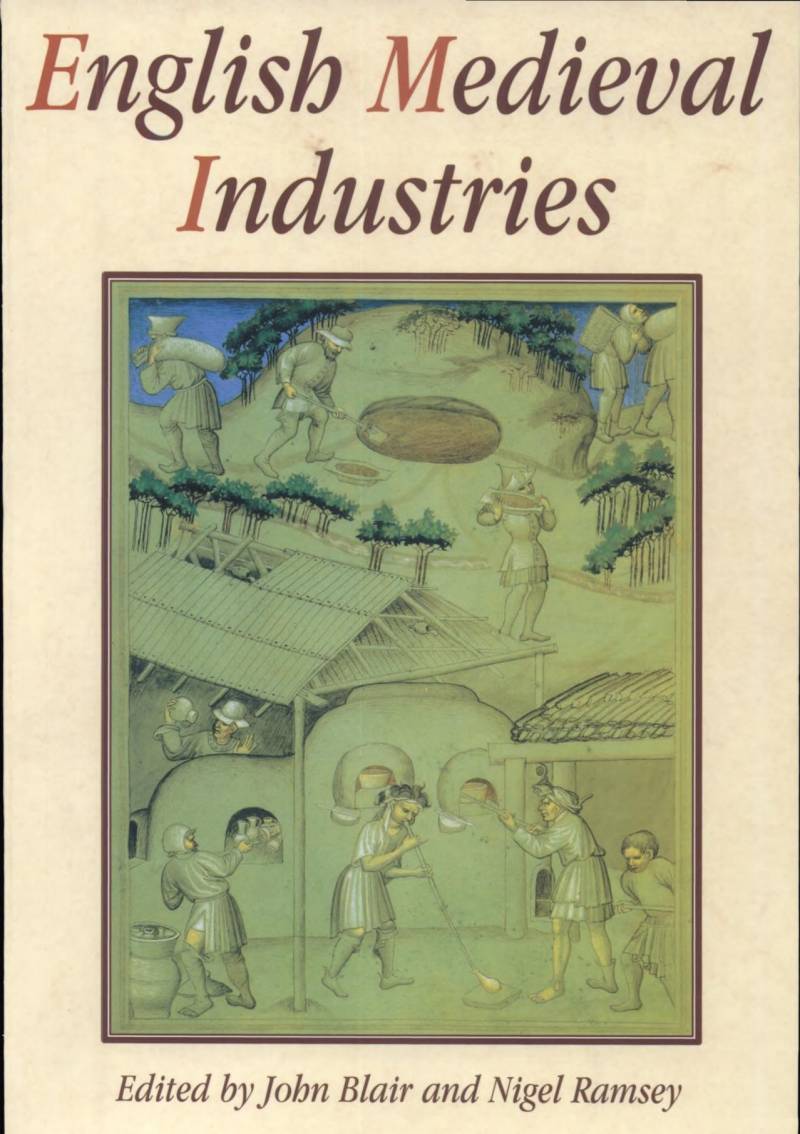

Secondly, I managed to find a book on medieval British industry: English Medieval Industries (John Blair, Nigel Ramsey, Hambledon Press, London, 1991, 446 p.). And what is there just not in it - both the early Norman period (1066-1100) and the medieval growth of production (1100-1290), it is clear that there is also something about the medieval economic crisis in it - the Great Famine and the Black Death (1290-1350) . Which was followed then by the "late medieval economic boom" (1350-1509). Products from leather and textiles, wood and bone, ceramics - all this is there, not to mention metal products. The book has been translated into Russian and the translation can be found on the Web, although the translation itself is not very literary. However, you can read, although through a stump-deck.

Here she is...

It’s just impossible to give illustrations from all the “Books of the 12 Brothers” - there are too many of them! However, it is very interesting to get acquainted with these two sources of information. Therefore, a kind of digest will be offered to the attention of VO readers - a summary of a book about the British iron and mining industry in England before 1500, and it will be illustrated, again, by “pictures” from “Books of 12 brothers”.

So, what kind of metals were mined in Britain in the Middle Ages and could they enable local blacksmiths to produce, let's say, the same weapon and knight armor?

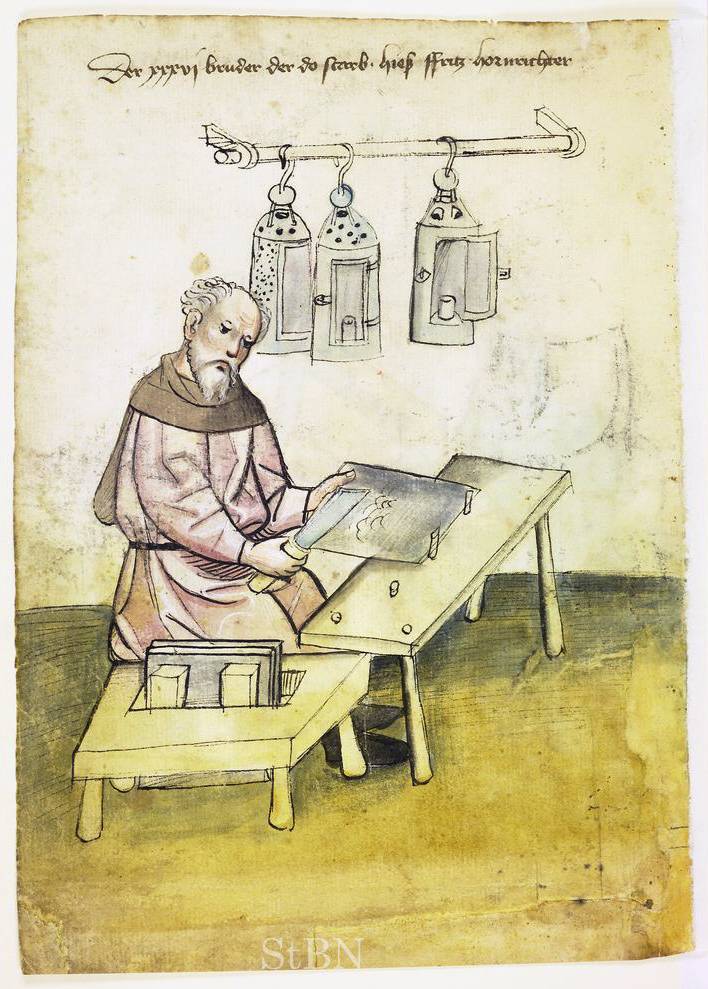

Master Lamplighter, 1425. With such lamps then they went at night

To begin with, from the Norman invasion in 1066 until the death of Henry VII in 1509, the economy of England was based on agriculture. However, the mining of iron, tin, lead and silver, and later coal, played an important role in the English medieval economy. William the Conqueror's system of government was feudal in the sense that the right to own land was tied to service to the king, but in many other respects the Norman invasion did little to change the nature of the English economy and its mining operations.

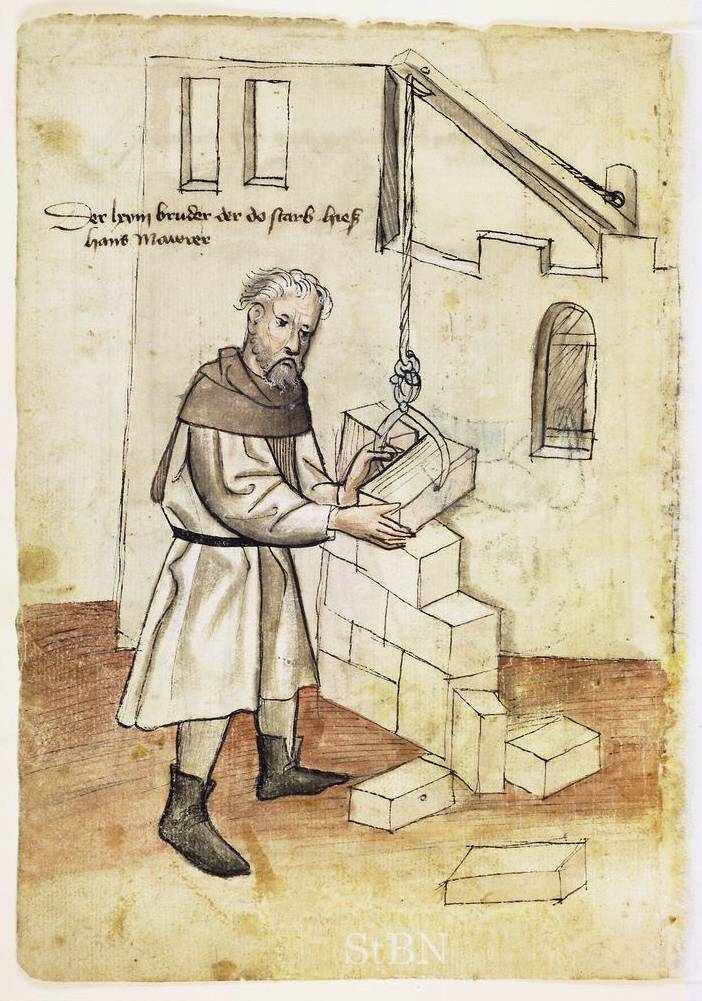

Bricklayer, 1425. Uses a crane!

At first, mining did not form a significant part of the English medieval economy, but in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries England experienced an increased demand for metals, thanks to a significant increase in population and the construction of buildings, including stately cathedrals and churches. During this period, four metals were mined in England: iron, tin, lead and silver using various refining methods.

Coal has also been mined since the 8th century. Iron was smelted in cheese blast furnaces to produce chicken, which was then carefully forged. Blowing into the furnace was carried out first with hand bellows, but then it was mechanized - they were driven by water mills. Domnitsa immediately increased in size and gradually began to turn into blast furnaces. Already in the XIV century, the height of blast furnaces reached XNUMX m. Since all these furnaces worked on charcoal, there was a massive deforestation for coal. The profession of a coal miner was popular, as it was not at all easy to get high-quality charcoal.

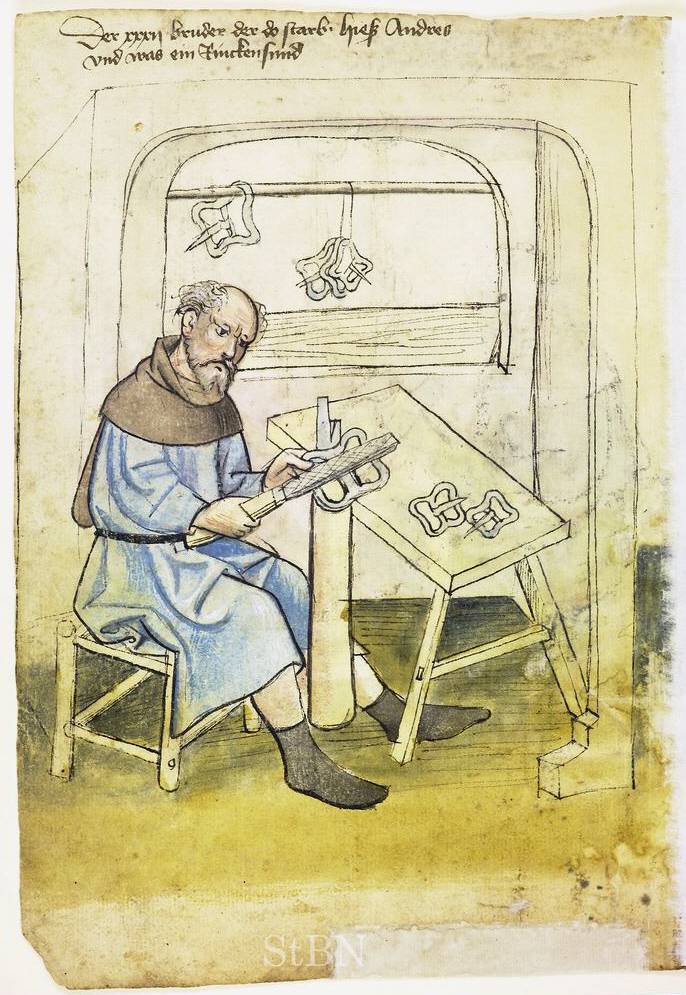

Belt buckle maker, 1425

As a result, deforestation to obtain charcoal led to the fact that already in the XNUMXth century in England it was forbidden to use charcoal in metallurgy. And this was a problem, because coke was only made and used in the XNUMXth century.

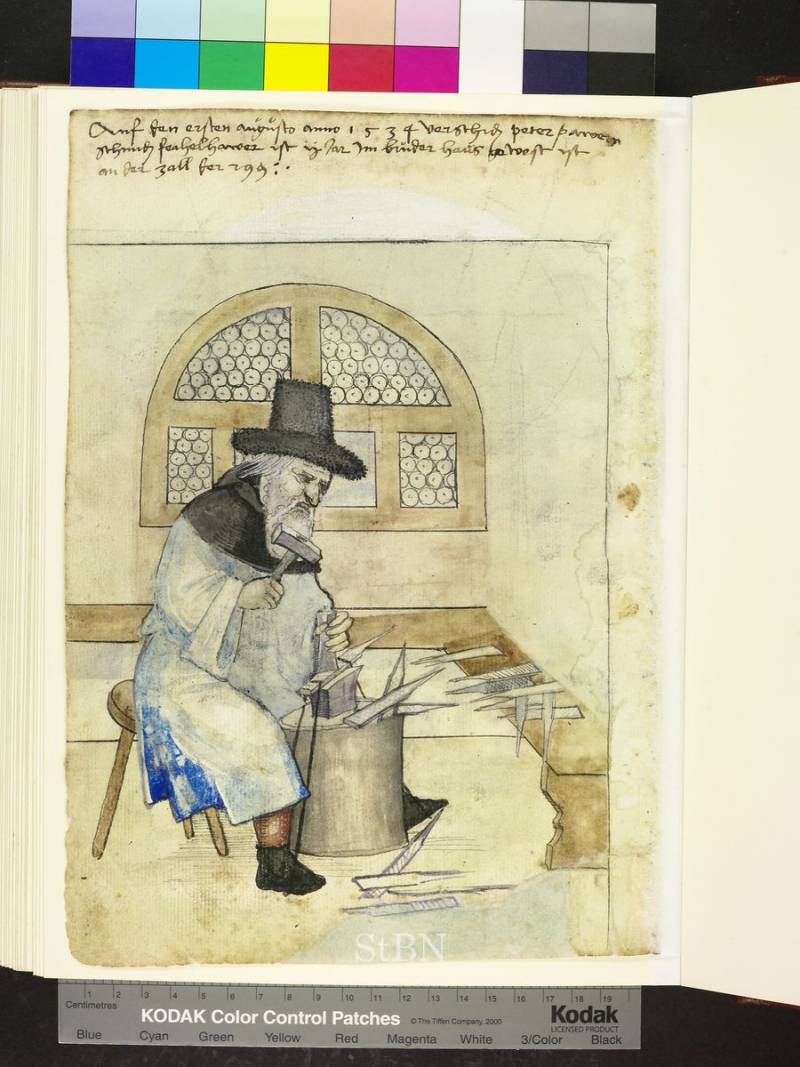

File maker, 1534

Iron mining took place at several locations, including the main center at Forest of Dean and Durham and the Weald. Some iron to meet the demand of England was imported from the continent, especially towards the end of the thirteenth century.

By the end of the XNUMXth century, the old stripping method of extracting iron ore was supplemented by more advanced technologies, including digging tunnels, trenches, and building mines. Iron ore was usually processed locally, and as early as the XNUMXth century, the first water-powered forge in England was built in Chingley. As a result of deforestation and the consequent increase in the cost of wood and charcoal, the demand for hard coal increased and it began to be mined commercially from quarry pits and by open pit mining.

Armor master. "Three-quarter" armor for a cuirassier or reiter hangs on the wall, 1535.

A silver boom occurred in England after the discovery of a silver deposit near Carlisle in 1133. Enormous quantities of silver were mined from the semi-circle of mines that ran through Cumberland, Durham and Northumberland - up to three to four tons of silver was mined each year, more than ten times the previous annual production across Europe. The result was a local economic boom and a major upswing in royal finances in the XNUMXth century.

Tin mining was concentrated in Cornwall and Devon, where alluvial deposits were mined, and managed by special "tin courts and parliaments" - tin was such a valuable export commodity. And at first it was taken to Germany, and then in the XIV century to the Netherlands.

Lead was commonly obtained as a by-product of silver mining in Yorkshire, Durham and the north, as well as in Devon. Lead mines usually survived as a result of subsidies from silver production.

The nailer used to make nails by hand!

The Black Death came to England in 1348 from Europe. But first, in 1315, the "Great Famine" came, which began a series of acute crises in the English agrarian economy. The famine was caused by a series of crop failures in 1315, 1316 and 1321, combined with an outbreak of epizootics among sheep and oxen between 1319 and 1321 and the spread of fungal diseases among the wheat stocks. During the famine that followed, many people died and the peasants were forced to eat horses, dogs, and cats, as well as cannibalize children, although reports of this kind are usually considered exaggerated. The Great Famine completely reversed population growth in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries and left the domestic economy deeply shaken, though not destroyed.

Then, in 1348, the plague first came to the land of England, after which it was successively repeated during 1360-1362, 1368-1369, 1375. and sporadically thereafter. The immediate consequence of this disaster was a mass death of people: about 27% of deaths among the upper classes and up to 40-70% among the peasants. Several settlements were simply abandoned during the epidemic, but many of them were badly damaged or were almost completely destroyed. The medieval authorities did everything possible to somehow respond to this challenge of the time, but the consequences provoked an economic crisis of exceptional force. Construction work stopped and many mine workings were abandoned.

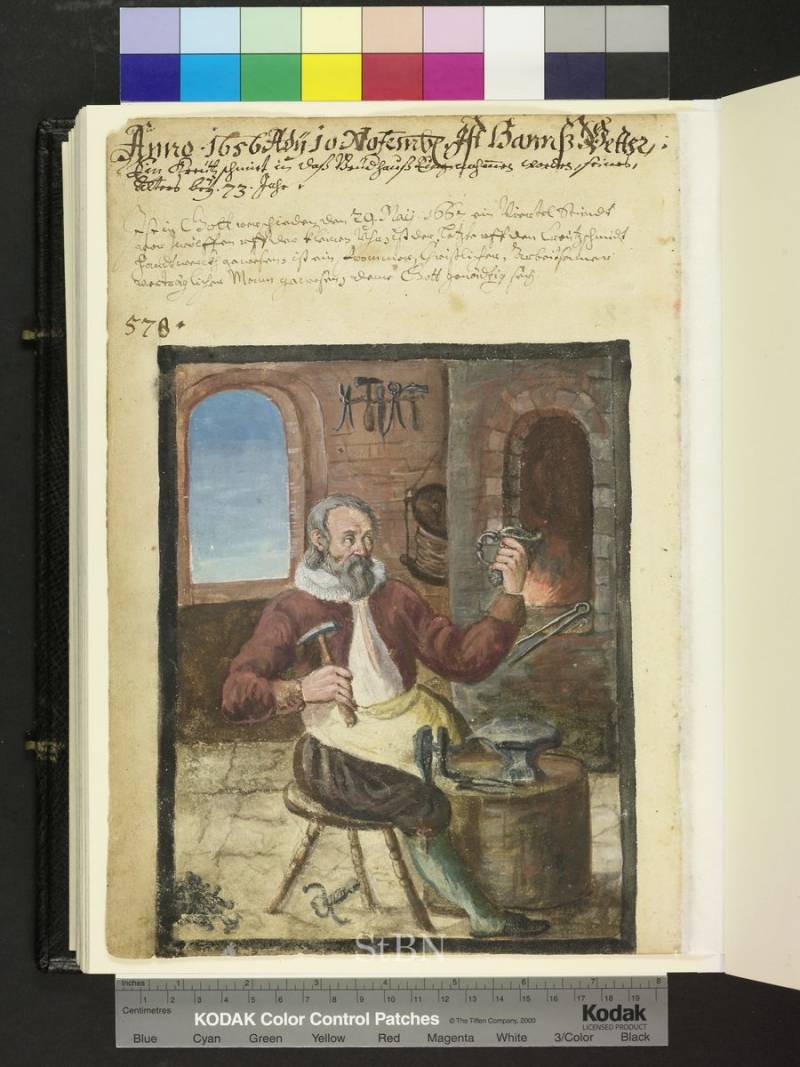

Master maker of sword handles, 1556

In the short term, the authorities made attempts to control wages and provide the population with pre-epidemic working conditions. However, unlike previous centuries of rapid growth, the English population did not recover this time for over a century. At the same time, the impact of the crisis on the English mining industry was felt until the end of the Middle Ages.

True in 1350-1509. the mining industry performed well overall, supported by strong demand for industrial and luxury goods. Production of Cornish tin plummeted during the Black Death itself, leading to a doubling of the price of its products. Tin exports also fell catastrophically, but rose again in the next few years.

By the early 1300th century, available alluvial tin deposits in Cornwall and Devon began to decline, leading to surface and underground mining to support the tin boom that occurred in the late 1500th century. Lead mining also increased, with production nearly doubling between XNUMX and XNUMX. Timber and charcoal became cheaper again after the Black Death, with the result that coal production declined, remaining at a low level until the end of this period - nevertheless, some coal mining took place, and all the main English coal deposits were used by the XNUMXth century.

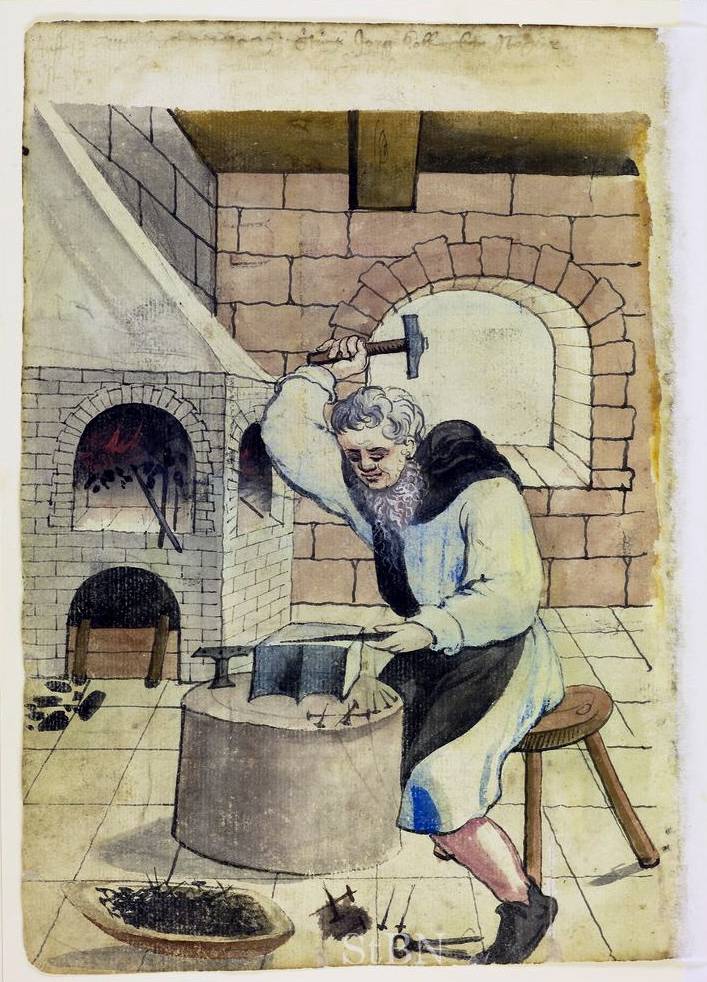

Blacksmith, 1564

Iron production continued to rise. In the south-east, more active use of hydropower began, but deforestation continued and reached the forest of Dean in the western part of Gloucestershire in England in the 1496th century. Well, the first blast furnace in England, which became a major technical step forward in the smelting of metals, was built in XNUMX in Newbridge, in the County of the Weald.

That is, the metal production of England between the Middle Ages and the New Age turned out to be at a fairly high level, and the metal itself, both iron and silver, with tin was quite enough to meet the needs of the corresponding production.

Gunsmith, 1613

Since we are primarily interested in the production of weapons, it is worth drawing a number of specific figures showing its level. For example, the production of 100 crossbow bolts required ten birch trunks and 000 kg of iron. At first glance it seems like a lot. But in fact, only in the Battle of Montleury in 250, 1465 arrows were used in one day! However, the British were constantly short of their weapons.

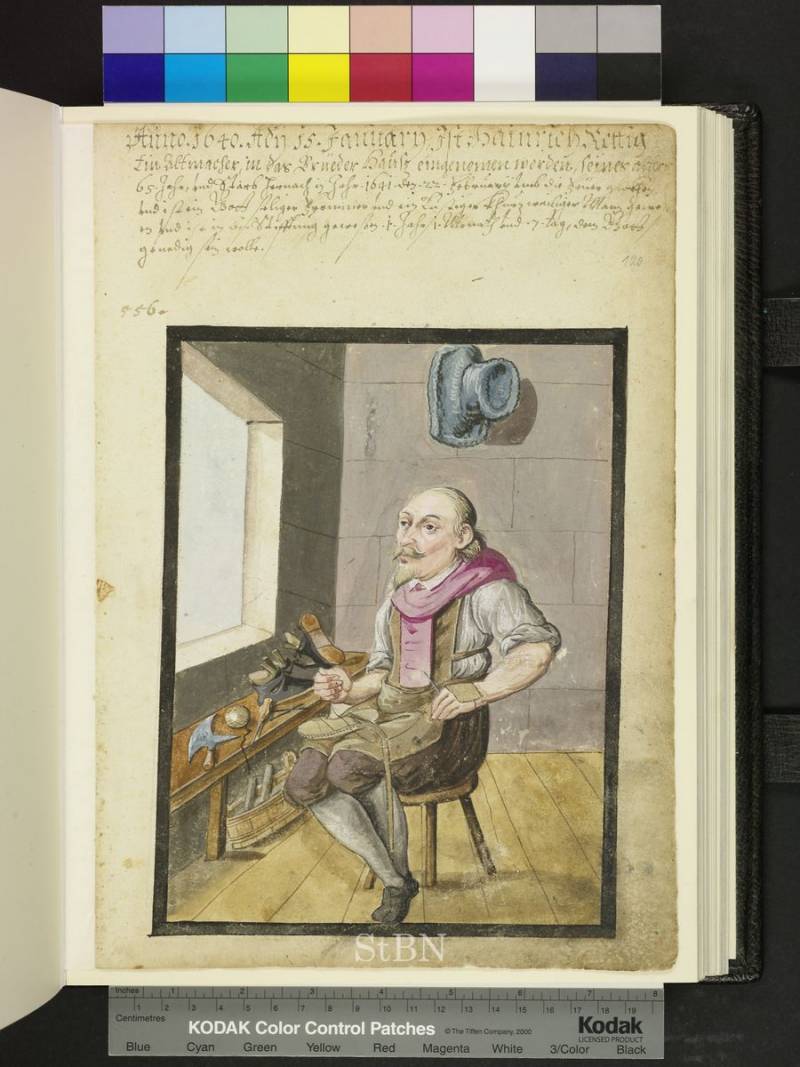

And this, of course, is a shoemaker. Well, where without him ... 1640

So, at the time of the death of King Henry VIII in 1547, the Arsenal in the Tower had 3 bows, and 060 bundles of arrows with 13 arrows each. The total number of arquebuses reached 050, but 24 arquebuses in 7 arrived in England from Brescia. In 700, Henry bought 4 sets of armor in Florence at a price of 000 shillings each, a year later another 1543 in Milan, then in 1512 he bought another 2 armor in Cologne and 000 in Antwerp. Also at the time of his death, 16 iron tools and 5 bronze ones were stored in the Tower.

Information