Expedition to the ancestors

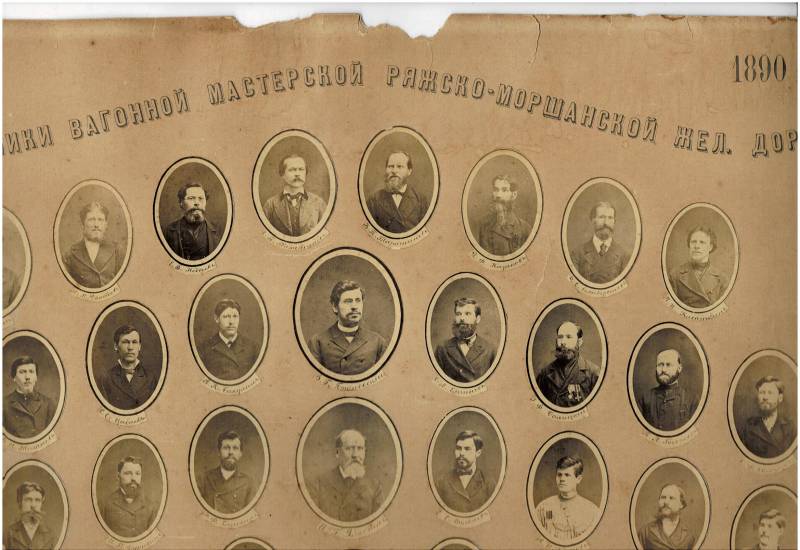

A very rare photo and, unfortunately, not completely fit. Workers of the carriage workshops of the Ryazhsko-Morshanskaya railway. Konstantin Taratynov, my great-grandfather, with his brother (left)

hitherto gave uninterrupted prosperity

and glory to our kingdom.

The Third Book of Maccabees, 6: 25

History recent past. Somehow, not very long ago, some readers of our site asked me to think about a series of articles about ... the past. Because life is changing rapidly, and from the past, even the Soviet one, not to mention the time before it, there is literally nothing left. The streets themselves change in such a way that if our grandparents were on them, they would not recognize them.

Of course, I can’t talk about some global moments. I was not familiar with the ministers, and of the secretaries of the Penza OK CPSU - only with the second, I saw the first only from a distance. But just as one can guess the existence of seas and oceans by a drop of water, so one quite ordinary everyday story can contain a lot of interesting things.

In addition, I was kind of lucky: having been born in 1954, I spent all my childhood with old people who were born before the revolution, in an old house filled with things of the XNUMXth century, and I partly received “that” upbringing ...

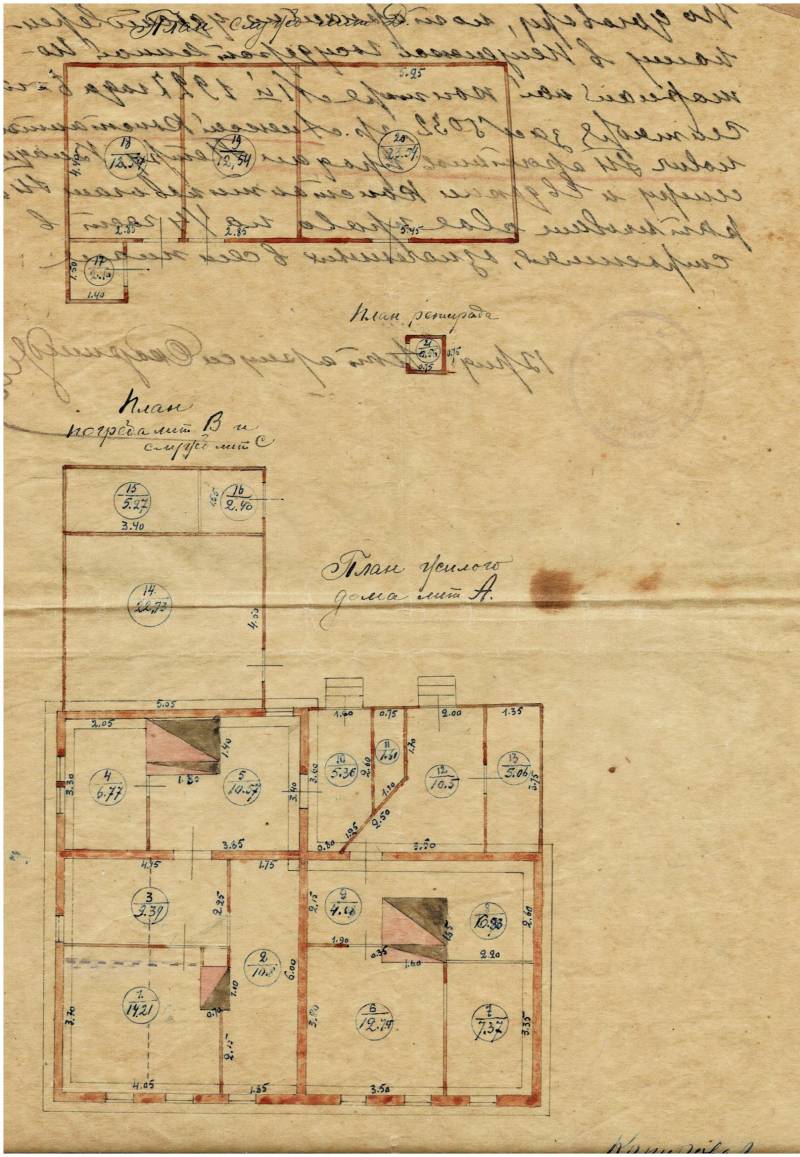

Plan of a house built by my great-grandfather in 1882. The right half - my grandfather Peter Konstantinovich, the left - his brother Vladimir and his sister Evdokia. He had a stove and a Dutch woman, and in general they lived together, and their living area was larger than ours. The drawing also marked all the sheds, and "retirades" (outhouses), as they were decently called then ...

And it so happened that one of my earliest memories refers, probably, to the age of four. I run out into the canopy of our wooden house, the morning is bright, sunny, and I touch some objects on the shelf in front of the window to the street, and I have an eerie, frightening feeling of deja vu that I have already touched all this once.

Then the porch, the courtyard, and in front of the barn the dog Rex runs on a chain, with one ear sticking out and the other drooping, which makes him look very stupid. I go to the garden, and it seems huge, there are a lot of bushes, trees in it, and you can hide there so that no one will find you with fire during the day. But the garden, as well as the yard where firewood is brought and dumped, are all summer pleasures, as well as playing with the neighbor boys in the neighboring yard.

And there are many courtyards along Proletarskaya Street, formerly Aleksandrovskaya Street, in fact, it all consists of separate households, fenced off from each other by wooden fences. Not far from our house, it was crossed by Mirskaya Street, named after the Penza governor Svyatopolk Mirsky. So there were no sidewalks at all on it, and people walked on broken ground, even when asphalt had already been laid on Proletarskaya.

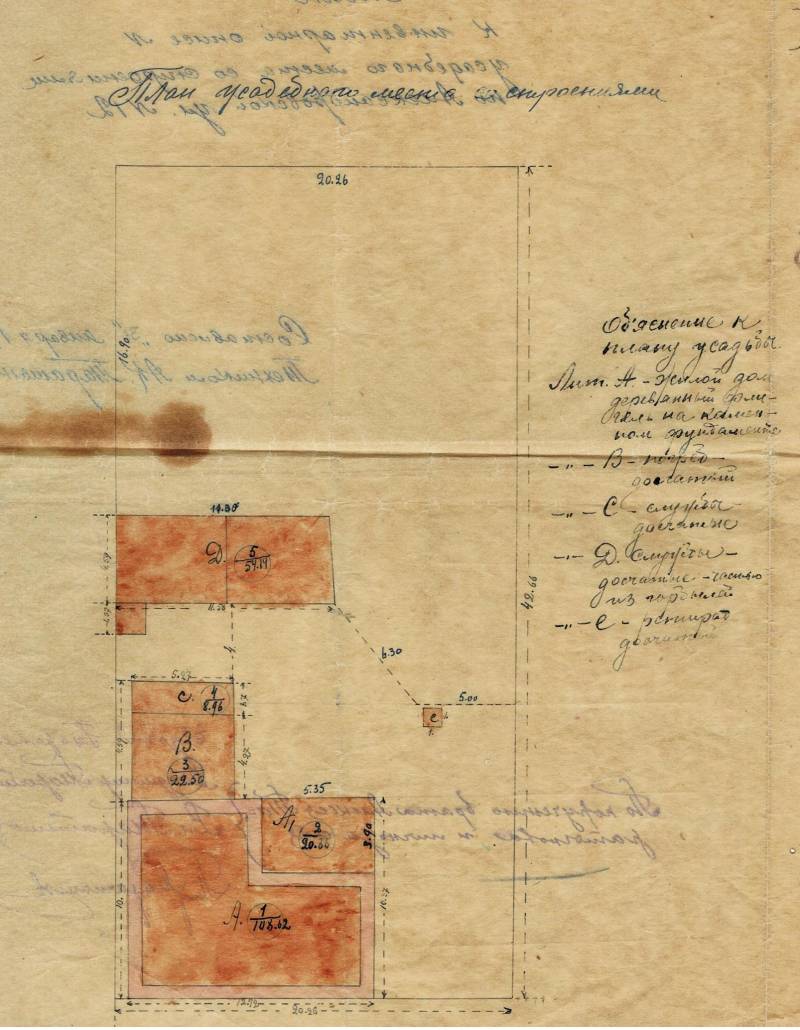

This is how the estate plans were drawn up at that time. The letters indicated what was what, and a brief description was given. The house, as you can see, was on a stone foundation (marked in pink), that is, the structure was very solid. Well, there was a lot of land near the house. The total area of the plot was 1 m

There is no asphalt on the pedestrian part yet. It's not on the road either. I am five and a half years old at this time, and I know this for sure, because my neighbors constantly ask me how old I am, and I answer - "five and a half." For some reason, I remember it.

Instead of asphalt, "sidewalks" were laid - boards on transverse logs. The boards are thick, but still flex when walking. And this is very cool, because in the spring water accumulates under the sidewalks, and when people step on a board with a loose branch, a fountain of cold water shoots up from there. And it's especially funny when such a fountain hits women under their skirts! Well, you just can't stop laughing.

Well, the roadway is covered with gravel, but all the same, the ruts on it are such that the “box” bus barely passes through it.

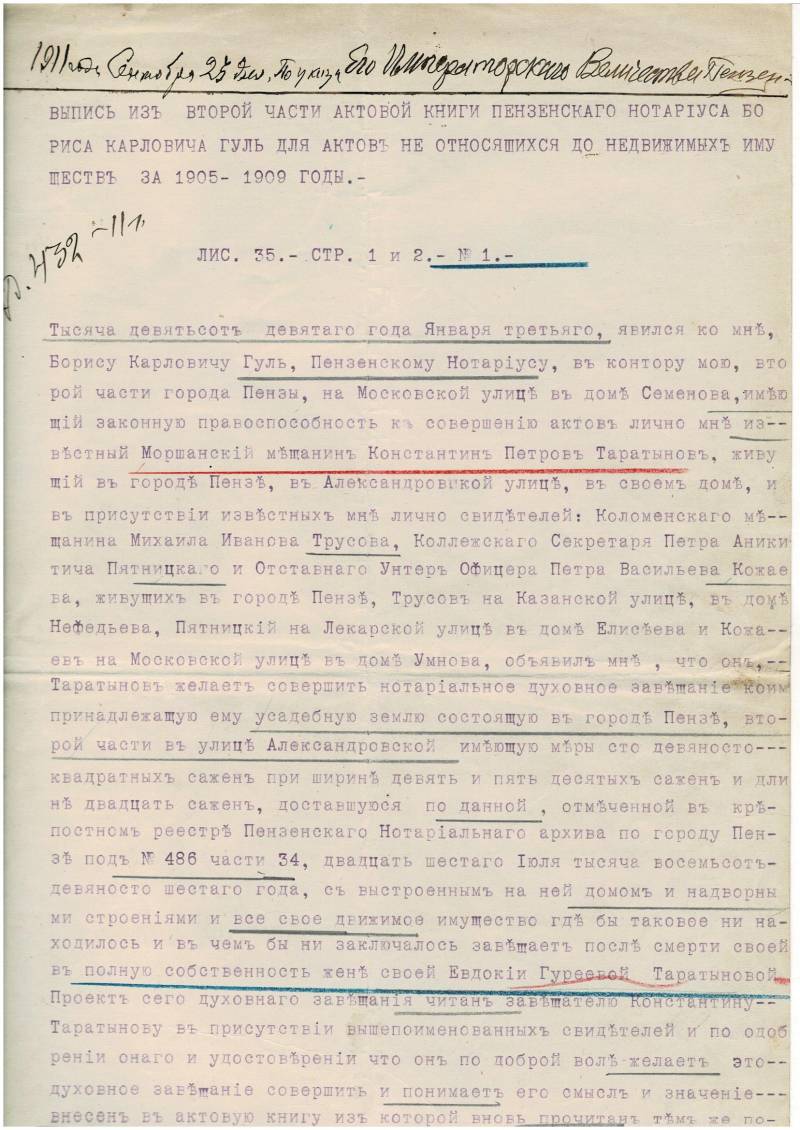

The text of the great-grandfather's will to his wife is already typed. Progress, however!

In the morning I always woke up from the creak of these sidewalks and the clatter of many feet - these were the workers in a continuous stream going to the mill. Then the screams of the milkmaids began: “Milk! Who needs milk! A grinder followed them: “We sharpen knives, we straighten razors!”, Then a junk dealer with a cart: “Shurum-burum, we take junk!” Here, involuntarily, I had to insert, run to the kitchen to wash over the washstand and ... So the day began.

But happily it began only in the summer. In autumn, winter and spring, my house was pretty boring.

Firstly, everyone in my family worked: my grandfather until 1961, when he retired at the age of 70, and then my grandmother left with him. He was the director of the school and taught geography and labor there, and his grandmother worked in the library.

I also found a time when my grandfather was arguing with my grandmother because she asked him to bring water from the pump, and in response he began to swear that “you are preventing me from getting ready for the“ chickens ”. This terrible word "kuroki" was remembered by me for the rest of my life. As a result, my mother, who came home from work, went to fetch water, and the incident was settled. But the "chicks" are remembered.

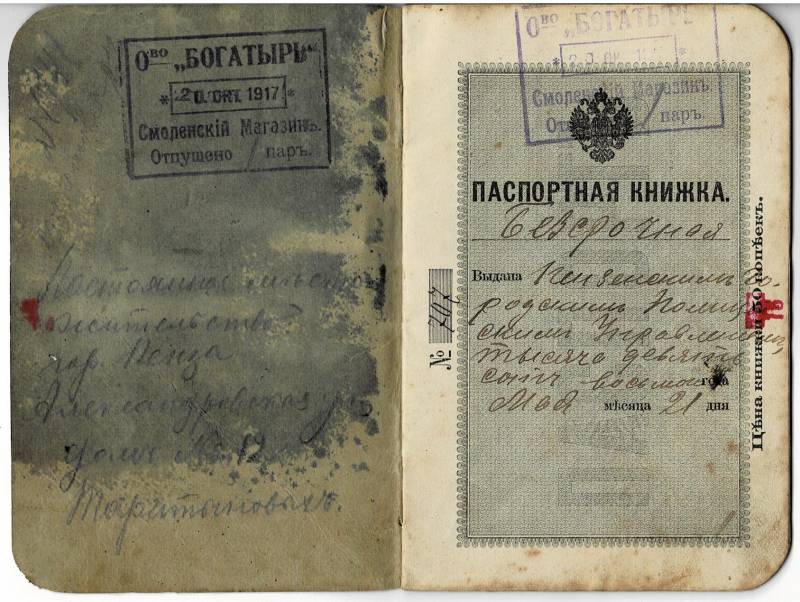

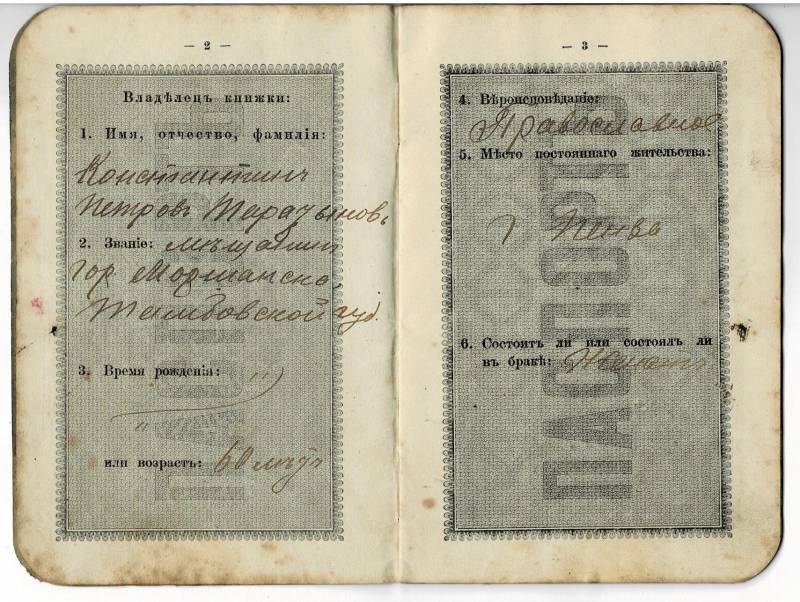

Passport book of Konstantin Taratynov

So until 1961, I had to stay at home alone very often for a long time. And it was boring, because I had already overlooked all the rooms in the house.

How about playing with toys? And there were few of them, then children were not spoiled with toys. There was a big bear that purred when I wrestled with it, a stuffed hare and a fox - my favorite childhood friends. There was also a groovy subway, but it had to be placed on the table in the hall, and this could not always be done.

They wanted to send me to a kindergarten, but when I found out that I would have to go there in the summer, I flatly refused, summer freedom was dearer to me than anything in the world.

Nationality was not indicated in the passports then. Religion was indicated - this was the main thing!

But back to the house.

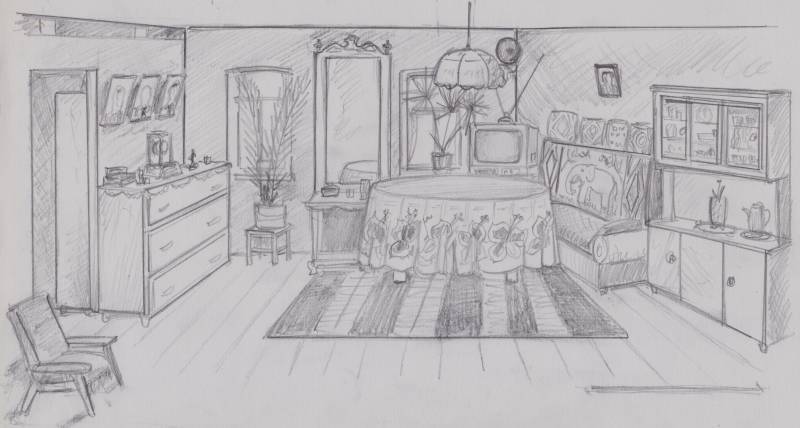

It had a large entrance hall with a closet, an entrance hall, where grandfather's bed stood against the wall, that is, he actually slept at the door, and in the hall there was a sideboard, a round table, a sofa on which grandmother slept, a chest of drawers with various knick-knacks and Moser watches. ". Above them hung, in the fashion of the time, large photographic portraits of my grandfather in his youth and his two sons, about whom I was told that they had died in the war.

In the same room, by the stove, there was also a large bookcase, and in front of the windows, on stools, there were tubs of palm trees, one date palm and the other fan. In the corner of the room in 1959, a television appeared, over which hung a black radio dish.

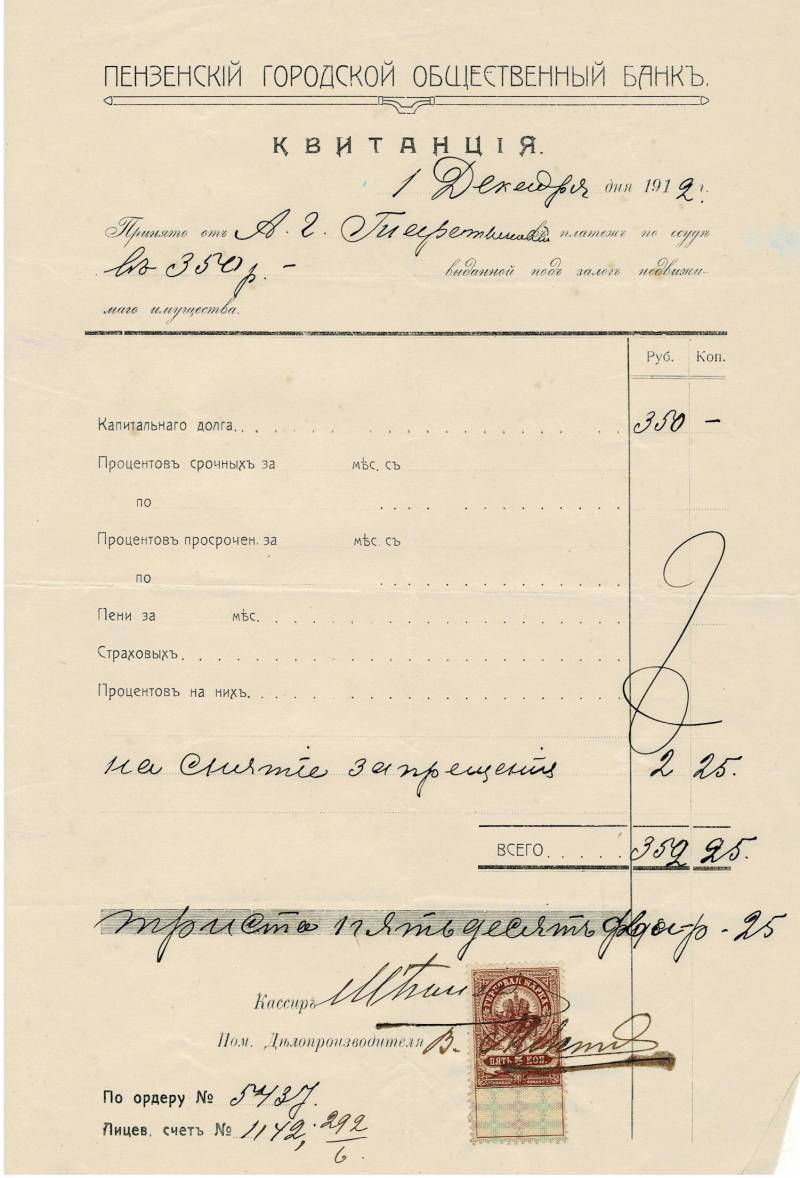

In 1912, they also took out loans from the bank ...

From the hall, a door led into a small bedroom, where my mother's bed and mine were placed, still with a grate so as not to fall out at night, a table at which grandfather and mother prepared "kurokam", and another mahogany table on one carved leg. On it stood a glass container with a mushroom floating in tea. I was ordered to drink it, and I still can't decide if I liked it or not.

View of the house from the street. The house differed from many houses on Proletarskaya in that it did not have a front porch overlooking the street, it had only a row of windows and a gate to the courtyard

In the kitchen there was a table at which all four of us ate, another cupboard full of grandfather's abstracts and pictures torn from books and pre-revolutionary encyclopedias, and a Saratov refrigerator. There was also an electric stove on it, on which they cooked when they did not heat the stove or because of the cold it was impossible to burn kerogas in the hallway.

By the way, in the same hallway there was also a deep, cold cellar lined with stone, in which we kept potatoes and ... we had to hide, as grandfather said, in case of war from bombs.

Interior view of the hall on "our half"

The stove took up a lot of space in the house. Huge, with a couch on top, it was to me both a knight's castle, and an uninhabited island, and a ship. One wall was made of wood. And I dragged from my grandfather his pictures from encyclopedias and glued them to this wall with plasticine, and then ... I talked to myself, telling myself stories related to them.

Many children talk to themselves, explain the game, but hardly anyone had so many beautiful color pictures from which it was simply impossible to look away: weapon North American Indians”, “Polynesian and his wife at the pirogue”, “Swallow's Nest in the Crimea”, “Eskimo Clothes”, “Eskimo Igloo” - these are just a small part of what was there.

There were a lot of old things in the house. Actually, the whole house was saturated with antiquity, and even in 1961, very little, except for the radio, TV and vacuum cleaner, differed from what was in it, let's say, in 1911! That is, half a century had very little effect on him, and I was also raised by middle-aged people: my grandfather was born in 1891, my grandmother was born in 1900.

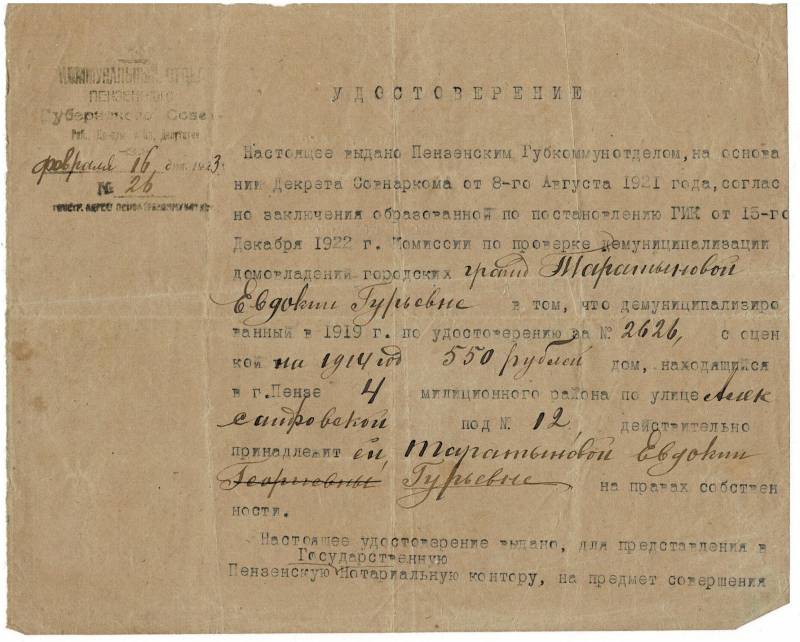

And here is a very interesting document issued to my great-grandmother - a certificate of demunicipalization of housing. That is, at first it was municipalized by the Soviet authorities, but then something did not grow together there, and it was returned to the owners again already in 1919. By the way, according to a 1914 estimate, the house costs 550 rubles!

It was somehow not customary to talk about the past then, and personally, if I managed to find out something about it, it was somehow in fits and starts when I asked questions about it.

For example, I was very interested in the sign on the door of our house: “Salamander Insurance Company”. We insure against fire "1882". As they explained to me, that year my great-grandfather built this house, but did not have time to insure it, and set it on fire the very first night. Who, why and for what - and did not find out.

My ancestors were saved by the fact that the fire tower was literally a hundred meters from us, and the fire cart arrived in time instantly. But the house had to be rebuilt, and the great-grandfather built a large barn out of the burnt logs.

The house was eventually divided into two families - my grandfather, in the family of the youngest, and the family of his brother Vladimir, who settled in the "other half" with his sister Dina. He did not marry, and she did not marry. She died in 1958 and he in 1961, so we also got part of his house. But part of us (with a stove, first one room, and then the second) was chopped off from us by another grandfather's sister Tatyana.

Here she was, this same Tatyana, in her youth, of course. She married an officer of the Cossack troops (only the rank on shoulder straps is almost impossible to consider), here he is next to her, and gave birth to two sons from him who died during the Great Patriotic War

In general, great-grandfather Konstantin Petrovich Tatarynov (1845–1910) had many children. He himself was a native of the city of Morshansk, a tradesman by social status, of the Orthodox religion. In Penza, his career went uphill, and he rose to the rank of foreman of the carriage workshops of the Ryazhsko-Morshanskaya railway, that is, he made an excellent career for a man from the people. According to his grandfather, he did not drink alcohol and did not smoke.

Her sister is Evdokia (Dina). Then these photos were very popular. Unfortunately, few of them have survived, and not all of them have it written who is who.

His family was big. In addition to his brother (no information could be found about him, it is only known that he also worked in the Penza railway workshops), he had a bunch of children: sons - Ilya, Alexei, Vladimir and Peter, and daughters - Tatyana, Evdokia, Olga. There were three more children (!), but they all died very early. His wife Evdokia Guryevna lived longer than her husband (1851-1923), and this despite so many births and a generally difficult life.

And now the most interesting thing is that all the children of Konstantin received an education, first they graduated from the gymnasium, and then continued their studies in all directions. Evdokia became a music teacher, Vladimir graduated from the physics and mathematics department of the university and became a mathematics teacher at the gymnasium, Tatyana became a French teacher. True, I won’t say who Ilya and Alexei became, but they each had their own house and left me a “legacy” of a whole bunch of aunts, one of whom later taught me chemistry at school.

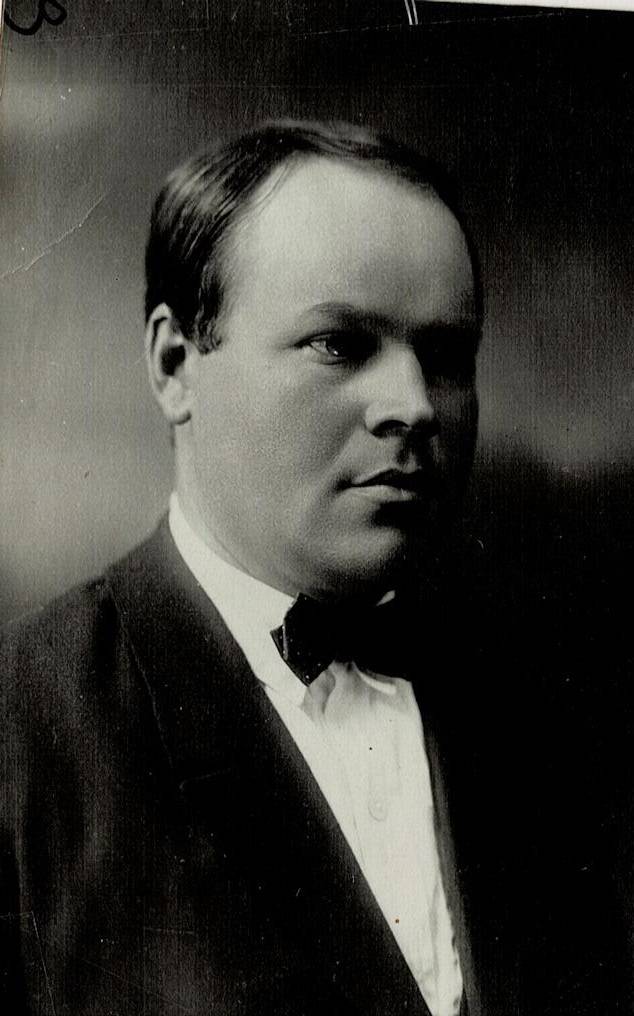

"Uncle Volodya" in 1932. Oh, and I didn't like him. Firstly, he always addressed my grandfather somehow condescendingly and called him Pierre as an older brother, demanded that I call him “grandfather”, and also liked to pat my cheeks, which were plump in childhood. Well, I took revenge on him in my own way: I bit the apples that had fallen from the tree and put them back on the ground. And, of course, he never admitted that it was I who bit them ...

But my grandfather didn’t want to study further, left the gymnasium, and became a “black sheep in the herd” - he went to his father’s workshops as a hammerer, because he had great strength and could be baptized with a pood weight! There, in three years, he earned himself an inguinal hernia and flat feet, which successfully avoided mobilization in the First World War.

He took up his mind after the death of his father. He graduated as an external student, first from a gymnasium, then from a teacher's institute, and in 1917 he met ... in the position of a teacher in a rural school.

And that's what's interesting, the family of a craftsman, but ... the right craftsman - and what is the result? All children could be educated. Build a big house with a farm. Which even got to me, his great-grandson. That is, the opportunity to rise from the bottom was high enough among the people of the ignoble and then ...

It is also a very rare, although popular at the time, photo of a team of workers from the Penza locomotive and carriage depot. Konstantin Taratynov is ninth from the left in the bottom row. But my grandfather, a very young guy, is third from the left

To be continued ...

Information